ILIR KALEMAJ Ph.D

Abstract

The latest show of solidarity after the biggest earthquake to hit Albania in decades from the Albanians of Kosovo, their government and people, was one of the series that witness the strong and lasting relationship between the two Albanian halves despite more than a century of arbitrary border between themselves. The recent earthquake made possible the outpouring aid from Kosovo, which has been yet another instance of brotherly help in times of crises. There have been till now 500,000 euros donated from the government of Kosovo and more than 3.5 million from the population of Kosovo till now. Also, 110 specialized operators and 40 members of the Kosovo Security Force search and rescue units have contributed to alleviate the needs of the suffering people in the post-earthquake situation. This was the latest instance of a relationship that is well established and tested through times. Proofs of solidarity are given time to time as to reinforce the brotherly relations between the two brethren states, as the example of more than 435,000 refugees that had to leave Kosovo for Albania in 1999 according to the UNHCR,[1] in the aftermath of ethnic cleansing by Milosević’s regime and that found refuge in Albania at the time.

This article explores the relations between Albania and Kosovo as they stand at the present and the likely trajectory they are going to take in the near future. The point of departure is the study of these relations from February 2008 when Kosovo proclaimed its independence and how the process of Kosovo`s recognition and state-building have influenced and conditioned its relationship with Albania. The discussion has involved the mainstream elite in both countries and several proposals have emerged since. On the other hand, a related debate on a Kosovar identity as a rather exclusive and new one versus the traditional understanding of the undivided Albanian identity seems to develop simultaneously with the participation of a substantial part of political and cultural elite on both sides of the border.

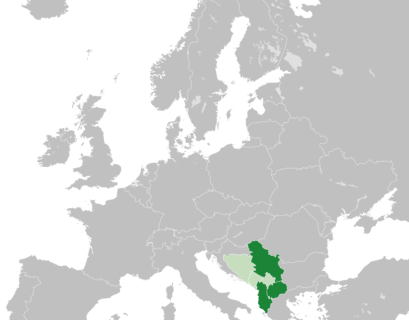

In this framework, stereotypes about “Great Albania” and unification of Kosovo with Albania persist and are part of the discourse in the Balkans, especially neighbors such as Serbia which have expressed certain fears about such developments. This phenomenon had seen attempts made by governments of both Albania and Kosovo, whose effects remain to be seen, ranging from unification of school curricula and textbooks to unification of consulates in certain countries to an energy union between the two countries. On the other hand, polls made by international organization, as well as local organization in Albania and whose data is presented below, do not show any massive popular support for “Greater Albania”, so fears mentioned above remain without a solid base.

However, recent evidence that is going to be duly analyzed in this study, testifies for a rising nationalist fervor in Albania versus a decline in Kosovo, which also relates to how masses and elites view the Albania-Kosovo future. In this analysis I offer an assessment of key internal and external factors that will influence the future of relations between Tirana and Pristina and make projections for possible scenarios of the bilateral relations in the next twenty to thirty years.

Introduction

Albania`s prime minister Edi Rama’s historic visit in Belgrade in November 10, 2014 was attended with much curiosity, expectations and attention from both domestic audiences in Serbia and Albania, as well as international interlocutors which made possible this visit in the first place. The culmination of the visit was in the press conference of the two leaders, where Rama declared that “[w]e have two entirely different positions on Kosovo, but the reality is one and unchangeable,” and adding that “[i]ndependent Kosovo is an undeniable regional and European reality, and it must be respected,” Serbia`s premier responded by saying that “[a]ccording to the constitution, Kosovo is Serbia and I am obliged to say that no one can humiliate Serbia.” To which Rama responded: “I’m sorry, but that is the reality that many recognize. The sooner you recognize (that), the sooner we can move ahead.”[2] These heated exchanges left in shadow the concrete achievements which were several deals that regulated the freedom of movement from citizens of countries, youth exchange and mutual diploma recognitions, as well as removing some trade barriers and coordinating police patrols in customs. But Rama also alleviated Serbia`s fear of Albania`s blocking role for Serbia in Euro-Atlantic forums, by explicitly saying that Albania will not block Serbia`s entrance in NATO.[3]

Even before the visit of premier Rama in Presevo valley, a Serbian territory mostly inhabited by ethnic Albanians, the Albanian ambassador in Kosovo, Qemal Minxhozi felt the need to be explicit: “Albania does not have in its agenda the ‘Greater Albania’ but instead the European integration.”[4] But in the same interview he adds that until the end of the present year, a unified standard between Albania and Kosovo regarding agricultural products will be reached and the same would be for several of other matters between the two countries.[5] This shows how Kosovo is continuing to be a crucial matter and a bone of contention in relations between Albania and Serbia but also the ambiguity of Tirana in relations to Kosovo.

Kosovo declared its independence from Serbia on February 17, 2008. Despite a strong objection from Serbia that was using diplomatic means to persuade countries not to recognize Kosovo, currently it is recognized by 106 countries worldwide. Additionally, Serbia and Kosovo with mediation of the EU reached in April 2013 a key agreement in normalizing relations by stipulating the abolishment of parallel institutions and the setting up of Municipalities of Serb majority community, which will function in accordance with the Kosovo laws.

Kosovo`s relation to Albania as its ‘mother country’ has been an everlasting question that has been especially salient in the decades that followed the uprising of 1981. Following Milosević`s ethnic cleansing and Albania`s hospitability for its Kosovar brethren under the auspices of UN and other international organization, the relations between now two equal states have been steady, friendly and often coordinated in matters of foreign policy, security etc. But these areas of close cooperation have clearly not been enough for nationalist and irredentists on both sides of borders, be that charismatic individuals, political parties or social movement groups. Debates on Kosovar identity as a separate one from the all-encompassing Albanian one has been taken place time after time, like the ones organized by Java in Pristina several years ago with its main spokesperson Migjen Kelmendi but also other public figures such as columnist Halil Matoshi etc. Even recently a similar debate about an Albanian inclusive nation versus a new and unique Kosovar one has taken place in the public arena, with distinguished Kosovo intellectuals writing for major dailies in both Kosovo and Albania. Such is the example of Shkelzen Maliqi, a leading Kosovo analyst and adviser of Primer Rama for Western Balkan region who writes inter alia:

It is the misinterpretation of the nation that creates confusion. The term ‘nation’ in itself incorporates all the ones that live in a state, notwithstanding their ethnic origin. In this sense, Kosovo nation should be composed of ethnic Albanians, but also Serbs, Turks, Roma etc (2014). But in the long-standing tradition, the ethnic Albanian communities and people have identified themselves as Albanian nation, despite the fact of residency. They are a nation wherever they happen to live- in Albania, Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro, Presevo valley and in various diasporas (Maliqi 2014).

He further develops his logic by adding a more theoretical input on the matter and how to understand the state-nation nexus. Thus, he adds:

According to the logic of some: because Kosovo is a new state, then we must have a new Kosovo nation; the Albanian nation exists only in Albania; in Macedonia, the Albanians should be considered with Macedonian nationality; the ones in Presevo valley as Serbs and so on… Kosovars of all ethnic compositions or nationalities will accept to be called Kosovar citizens but we should not allow a forced acceptance of Kosovar nationality on Serb minority. Also, the Albanians of Macedonia do not refuse to be citizens of Macedonia, but they are categorical against a Macedonian nationality. Some Kosovo intellectuals` narrative projects nationality and also a Kosovar language that should be separated from the Albanian trunk. I think that this is an absurd tendency. Because history has been unfair to us, they want culture to be unfair to us as well (Maliqi 2014).

Nexhmedin Spahiu, a renowned analyst from Mitrovica directly rebuked Maliqi`s claim by writing that “Shkelzen Maliqi, same as the former Serbian President Tadić, does not recognize the existence of a Kosovar nation.” He continues by adding that “a Kosovar nation is defined 20 years ago from him and in science the copyright goes to the one that first operationalizes a term.” For Spahiu the Kosovar nation is made only of the Albanian community of Kosovo, thus excluding Serbs, Roma, Turks, etc. He claims to be on the same line with Marti Ahtissari`s plan. He grounds his argument on the fact that Kosovo has its own national library, national theatre, national football team, as well as national political parties which differently from the minority parties have to gain more than 5 percent of the votes to pass the parliamentary threshold (Spahiu 2014).

This up to date discussion about the identity of a Kosovar nation includes both an internal and an external dimension. The internal one has to do with Kosovo being an inclusive or exclusive entity vis-à-vis its non-Albanian ethnic groups, while the external aspect is directly related to the presumed relationship Kosovo should have with Albania. What these authors project in this short rebuke to each other is a view of what should be the future of the new state. Should it stand alone and try to develop a new identity through state formation mechanisms that anticipate nation-building? Or should it rather base the concept of the state on the predominantly Albanian nation and thus leave open the opportunity for a potential unification of the two Albanian states?

Between these two extreme positions there is of course, an additional salient element to be considered is the integration process in European Union. Other proxies include the position of Serbia, the sensitivities of Macedonia because of its large Albanian community and other neighboring countries concerns if Albania-Kosovo potential federalization goes under way. The EU integration process in itself is considered by a non-significant part of Kosovar political spectrum, as well as public opinion as a facilitator of de facto unification amongst the two states and their respective citizens. An example of this is Vetvendosja, the third largest party in Kosovo but considered the main opposition party and in charge of the capital city whose belief is that the integration process will enable the two countries to finally come together. This is a view shared by their counterparts in Albania, such as Aleanca Kuqezi and Lista Natyrale, although of much lesser political effect. The majority in both sides of the border and mainstream political parties actually believe that no border change will take place, or that borders themselves will be irrelevant when finally, Albania, Kosovo and the rest of the region will become part of the European family. But in both of these last scenarios, Kosovo and Albania will not end up together in a federation, confederation or whatever form desired by nationalists.

Short overview of Albania-Kosovo historical relations

Albania has lacked a consistent approach toward the ethnic Albanians of (former) Yugoslavia in general and the Albanians of Kosovo in particular. This has had several reasons, which I am briefly listing below.

First of all, it has been the geopolitical and ideological context in the interwar and communist periods. The passing from the monarchical period of Serbian-Croatian-Slovenes Kingdom, which from 1928 became the Yugoslav Kingdom, toward the supra-nationalist communist ideology. This has been a period when Belgrade has often had considerable power over the fate and lives of the ethnic Albanians outside Albania`s frontiers but also over Tirana`s government and has resulted in periodic fluctuations in the relationship between the two countries.

Secondly, close alliances in certain periods and open enmity in others have been characteristic for Belgrade-Tirana relations. Passing into various love-hate phases during Zog`s and Noli`s government in interwar period, where the first had a close relation to Yugoslav Premier Pasić. Zog and Pasić had an agreement that included exchange of territories, as well as military and financial support. While Bishop Noli had among his closest collaborators, notables such as H. Prishtina, B. Curri or Azem and Shote Galica who were leaders of anti-Belgrade resistance in Kosovo. During communism we witness two main phases: the first in the period from 1944 to 1948 where Tirana was highly dependent on Belgrade and a considerable cooling between the two in the aftermath. In the first period Tirana declined any cooperation with its ‘brethren’ outside state borders and participated even in notorious massacres such as the one in Tivar, where hundreds of Kosovar Albanians were killed. After the Constitution of 1974 that Tito introduced as a counter-mechanism to Serbian power within Politburo and state structures and the degree of relative freedom that the Albanians of Kosovo experiences, Tirana saw a window of opportunity to intervene on their behalf and to start using direct influence there. In the post-communism period, it was then the former opposition head, Sali Berisha who first advocated the unification of all Albanians in a single state but everything was purely rhetorical. After being elected as President he backtracked from earlier statements and by 1994 called Kosovo issue an internal question of former Yugoslavia, same as his socialist successor Fatos Nano who in a meeting with Milosevic in Greece called Kosovo an internal human right issue for Serbia.

Thirdly, Albania has always been weaker politically, militarily and diplomatically isolated, as well as economically deprived, compared to both Yugoslavia and Serbia in all aforementioned periods and this has normally been reflected in Tirana`s attitude toward its Albanian ‘brethren’ outside state frontiers.

Fourthly, the lack of a consolidated political thought and diplomatic agenda has made Tirana generally reactive and not proactive in its relations to Belgrade while the neighboring country has had well-structured elaborates such as Nacertanija of Garashanin, or the 1937 “Expulsion of Arnauts” of Cubrilović or the 1986 Memorandum of Cosić et al., which unfortunately are turned later in official discriminatory policy against the Albanians.

Differently from its immediate neighbors, Albania has had difficulties in linking its multi-confessional nature and pervasive societal divides to its developing national identity in the initial stages of nation-building. The other Balkan countries, not only started this process much earlier, but in addition had a high symbiosis between a dominant religion and the newly emerging national identity where the religion often served as bedrock of the latter. As Nicola Pedrazzi has summarized recently: “Albania features no obvious religious conflicts; even so, the fact remains that, as happens in other areas of the intricate Balkan puzzle, also in Albania – and especially for ethnic Albanians who live outside the boundaries of the Albanian state – religious affiliation is doubly tied to the identity question and has, therefore, also a political dimension” (Pedrazzi 2014).

The historical relationship between Albania and Kosovo and particularly the different trajectories they had both taken as the result of geopolitical pressures and domestic developments, is important in our understanding of the present and prediction of the future.

Recent findings from surveys and polls that measure bottom up perception

A 2010 poll, conducted by Gallup in cooperation with the European Fund for the Balkans, showed that 62% of respondents in Albania and 81% in Kosovo supported the formation of a Greater Albania.[6] The vast majority of respondents, more than 95% overall in the two countries, said that if such a “Greater Albania” was created, it should include Albania, Kosovo and part of Macedonia. Support is much lower for the union only of Albania and Kosovo. Only 33.7% of respondents in Albania approved of this solution, as did 29.2% in Kosovo and a mere 7.2% in Macedonia. These new data serve both as a testimony of shifts noticed and analyzed in the present study, as well as empirical indications that (should) inform policy and taken into consideration by international organizations, EU structures and other interested third parties. Contradicting data from Gallup polls, a 2010 survey taken by Albanian Institute for International Relations (AIIS) reveal an altogether different picture: from the poll sample in Albania, 37 percent of the interviewed people think that the unification of Albania with Kosovo is neither positive, nor negative, 35 percent think that it is negative and only 9 percent think of it as positive. The majority (35 percent) think that the possibility of unification Albania-Kosovo is slim, 18 percent think of it in average terms and only 9 percent think it is possible. As it can be seen, there is a correlation of numbers between those that think that unification is desired and also possible, while it is slightly less for the other categories of possibility of odds that something like this will ever happen. The poll continues by emphasizing another empirical finding that if the organization for unification of Albania with Kosovo would happen sometime in the near future, then 39 percent of the people that were interviewed were going to vote in favor of reunification, 23 percent against, 21 percent would have abstained and 18 percent would not participate. This data gives us an understanding of the perception of the nation and its mental borders from below. How nation is imagined, what are the chances of border shifts and potential reunification and how much this is desired by the common folk in both sides of the border? As it may be summarized from the above data, approximately same percentage of people (around 35-39 percent) believes that reunification is not possible, but that on the other hand would have voted for reunification is a referendum is possible.

The popular culture have remained largely expansionist in the last two decades in Kosovo, which has constrained political elite into nationalist outbidding with opposition parties usually being more in favor of any unification/expansionary scheme and the ones in government largely more restrained as the result of external constraints, but in Albania the opposite has happened where we witness the elite struggles and political shifts to have much impacted popular grassroots culture.

While referring to polls and surveys that measure shifts in mass-perceptions in Albanian populations in Albania, Kosovo and Macedonia, it is interested to note that in the elite level in Kosovo we generally witness two different currents in the post-independence phase. The dominant one, mostly represented by the political forces that constitute the majority are firmly positioned in maintaining the existing map, which guarantees a fully sovereign Kosovo that has only diplomatic links with Albania. This is based on two primary considerations. The first being the pressure of international community, who adamantly opposes any changes in borders and second, the consideration of politicians in charge of ruling the country who risk losing (existing) power in the advent of any possible unification scheme. However, the main opposition Vetvendosja[7] has as primary goal the unification of Kosovo with Albania, including Northern Mitrovica and has called for a referendum for its realization. Currently, some new developments are happening in Kosovar politics where a group of deputes requested such unification to take place.[8]

With government changes in Tirana following 2013 elections, there seems to be a reinvigorated attempt to strengthen the cooperation between Albania and Kosovo in several levels. For example, in a tour to Gjakova and Pejë, Prime Minister Rama gave warranties of taking out the double added value taxation for the books, newspapers and magazines. Also, there was a discussion for eliminating double taxation for steel products and a common evaluation of customs procedures, thus strengthening both the economic and cultural integration as a symbolic form of de facto unification.

Other steps undertaken by the Rama government include removing some of the frontier barriers between the two countries. One of these is the removal of worker barriers for the Albanians of Kosovo and Presevo Valley, who can work in Albania now without any obstacle. This puts the Albanians from Kosovo and South Serbia in a completely different category from every foreign worker in Albania who needs to have worker permit and residency to work in the country. The Minister of Welfare and Youth recently declared that: “[w]e liberalized the job market with Kosovo. The Albanians from Kosovo do not need to apply from now on for work certificates or work permits. Every citizen from Kosovo and Presevo Valley may apply for job in Albania.” According to him, differently from the previous government, “we do not consider as foreigners the Albanians of Presevo Valley, and thus every citizen from there can freely work in Albania.” Whereas, the primer Rama has promised to remove the barriers between the two countries to create common markets, common customary union, common sanitary certification and a new Economic National Council for both Albania and Kosovo.[9]

The idea is to further expand the areas of cooperation between Albania and Kosovo, which for some time now have developed a strategic partnership. How to move beyond this into more tangible results that can further bilateral relations without endangering regional stability and provoking geopolitical concerns from Serbia and other neighboring countries is a challenge in itself. Albania-Kosovo relations should be seen through the perspective of other regional countries and the intrinsic relations that Albania has built or plans to build in the near future.

Seen from this light, Artur Zheji, a commentator from Albania has argued that Albania has very close links with some of the neighboring countries. For example, he mentions Macedonia where as it puts “Albania is a stakeholder in 35%” of the territory referring of course to the percentage that Albanians claim to have on it. He goes on by adding that same can be even more true for Kosovo that is “conceptual and real part of same [Albanian] land, with Montenegro where [Albania] has its own land and people, with Greece, with which is often misunderstood based on a century ongoing conflict, with Serbia that it fought an epic war just recently….” (Zheji 2014). He continues by stressing that despite all these ‘natural’ comparative advantages, Albania has never used conflict to achieve aims, although as Zheji puts it this is more because the Albanian elites have preferred corruption and comfort rather than geopolitical adventures. He concludes by writing that we cannot take the past for granted “because the Albanian capacity for interaction can quickly turn a destabilizing one. Thus, it must be integrated” (Zheji 2014).

Another analyst from Albania, Afrim Krasniqi points at how demagogic is the language of political elite in Kosovo and Albania where they simultaneously speak of spiritual and cultural unification, economic common perspective and complimentary processes in other matters while in practice the reality is completely different. For example, in the field of mass media, Krasniqi writes: “each of the parties operates with the ways and means of the other, transmitting the news from the other country without proper verification and the derogatory language of Pristina is transmitted in Tirana and vice versa” (Krasniqi 2014). Also, as the author notes, the newspapers, magazines, books etc., of Albania do not reach Kosovo and same for those of Kosovo where the Albania`s market seems closed. Even political influence is very limited not only in the direction of Pristina-Tirana but also of Tirana-Pristina, given the putative role of Albania as the “mother” country.

Thus, the reification of Tirana as the epicenter of the Albanian nation and its political, cultural and socio-economic significance, seem to be mostly in name but not as matter of fact. Although various politicians can be found at any time in both countries who try to instrumentalize the “National Questions” for daily political gains, what is important is assessing how much of the public ear these tirades capture. The problems are the same in the two countries despite much fuss, but in some occasions, there are major public splits, like in the case of Kadare-Qosja debate where major public figures coalesced around the two thinkers, although not necessarily in respective state lines. In other words, it is not that Kosovars went automatically to rally behind Qosja and the Albanians of Albania behind their most prominent writer, Mr. Kadare. Generally speaking, the support for Kadare was greater on both sides of the border and not just because of his public and intellectual statute but also because his pro-West thesis found more resonance among the public opinion.

International Community and Kosovo Development

EU’s Political, Judicial, Technical and Financial Support to Kosovo

European Union has been particularly influential in setting up the pace regarding Kosovo`s normalization process. It has done so through its common mechanisms of “sticks and carrots”, or to put it otherwise through a package of incentives and conditionality that has sought to integrate Kosovo while making sure that reforms are completed. EU has several mechanisms in hand to do so. Forts of all, through the leadership of Baroness Ashton, the former foreign policy leading figure in EU has tried to break ground in relations between Belgrade and Pristina by creating the opportunity for Dacić (former Serbian primer) and Thaçi to sit, discuss and agree on a variety of issues that range from archives to security, from extra-territorial jurisdiction of Serbian enclaves and religious cults in Kosovo to protection of rights of minorities. The broken negotiations and agreements have been stepping stones for a lasting regional peace and the integration process of the whole region, which could also open the road for Kosovo to be first recognized by the remaining European countries that have not done yet sot and later aspire to integrate in the EU itself.

Regarding this last point, although up to the present moment, five European states (Greece, Slovakia, Romania, Spain and Cyprus) have not yet recognized Kosovo officially, the dual process initiated in tandem with Serbia under the tutelage of the European Union, itself is a good omen to the process. Moreover, a EU based mission in Kosovo, EULEX, has played a crucial role for its security and justice system, despite present-day corruption allegations, which have led the new EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Federica Mogherini to announce the enlisting of “an independent expert for a probe into allegations of corruption in the European Union rule of law mission.”[10]

UN role in Kosovo in the aftermath of independence

United Nation`s role in Kosovo after independence period has also been instrumental regarding the establishment of a climate of security especially in north of the country (Northern Mitrovica), where Kosovo`s government`s authority has been lacking, though chiefly not for its fault. UNMIK has been the UN`s mission in Kosovo from 1999 after it was established with resolution 1244 of the Security Council. As it is mentioned explicitly in its website: “the objective of the Mission has been the promotion of security, stability and respect for human rights in Kosovo through engagement with all communities in Kosovo, with the leadership in Pristina and Belgrade, and with regional and international actors, including the European Union Rule of Law Mission in Kosovo (EULEX), the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE). Meanwhile, KFOR has remained on the ground to provide necessary security presence in Kosovo.”[11]

UNMIK`s role has had a lot of overlapping with other international missions in Kosovo chiefly EULEX and KFOR, but also OSCE, different embassies, particularly the role and weight of US Embassy etc. Lately the role and impact have shrank to a considerable degree from the peak point when Ban Ki Moon, the UN General Secretary was proposing his (in)famous six-point plan.[12] The plan was contradicted almost in unison from Kosovar political elite, an opposition that found ambiguous reception in Tirana because the former Foreign Minister Besnik Mustafai was in fact in favor of a “limited independence” clause for Kosovo. This fitted with Ban Ki Moon plan that was especially sensitive in its recommendations regarding boundaries and Serbian patrimony.[13]

USA role and impact from independence to present day

USA has been a leading actor from the start in the Kosovo conflict, when it took the leading role to mobilize NATO and start bombing Serbian military facilities in a seventy two day campaign after Milosević failed to stop the ethnic cleansing process that resulted in thousands of Kosovar Albanians losing their lives and others to simply perish or be forcibly deported from their homes and property. Naturally USA`s government was not the only actor with great impact in the process. Great Britain played an equally pivotal role in the process under the charismatic leadership of Tony Blair, whose formulation of the new and revolutionizing concept of “humanitarian intervention”, added great value to the operation that made possible the liberation of Kosovo.

The United States government and its representatives in Pristina have also been a crucial factor that has impacted the state-building process in Kosovo and with great acumen in domestic political affairs.[14] They have also had same influence in Albania, FYROM and the other Western Balkan countries, although to a lesser degree. That influence is often of a greater degree than that of the EU missions, although in the case of Kosovo probably they are of similar weight but in different planes.

Albania’s position toward the EU Integration and how it relates to Albania-Kosovo future

Albania is way ahead of the newcomer state of Kosovo in its path toward European integration. After a considerable degree of slowness following the violent events in 1997, after which Albania had to join the former Yugoslav republics in association-stabilization negotiations with the European Union, Albania could finally sign its Association-Stabilization Agreement (ASA) in 2002 and then move forward with its reforms. Unfortunately, Albania had to wait for a considerably longer period than its neighbors such as Croatia and FYROM, which signed their candidacy status as early as 2004 and Croatia even succeeded into getting full accession in EU in June 2013.

Furthermore, Albania was bypassed even from the new state of Montenegro that became independent only in 2006 and signed its candidacy status in 2010. It later opened the negotiation for full membership in 29 June 2012. Albania was sidelined even from Serbia thatsigned its candidacy status in October 22 of 2011, despite having signed its ASA only in 2007, five years after Albania. It then opened its negotiations for full membership in European Union in January of 2014.

Albania`s considerable advance vis-à-vis Kosovo in its race to join the EU, makes Albania abide to rules and regulations, which include certain standards that cannot be overlooked in the name of the good friendship with Kosovo. One of these has to do with the acquis communitaire and the different laws and directives of EU that Albania has to abide. The latest such example was flour import from Kosovo which did not fully subscribe to EU criteria and in addition, its nutritional levels were below the EU standard requirements.[15] This followed yet other trade wars between the two countries,[16] which despite the real motivations or reasons have been justified on the basis of EU required norms, especially by Albania, which is a step ahead than Kosovo in its integration process.

Kosovo`s position toward the EU Integration and how it relates to Albania-Kosovo future

Kosovo has several difficulties in its rocky road to become a full-fledged European Union member. One of these is the fact that is a newly independent country. It declared its independence only in February of 2008. To make things even more complicated it is recognized only by a bit more than half of world countries,[17] so its recognition it is not yet universally accepted and what matters most for our discussion here, it is still not recognized as a sovereign state by five of the EU members states. The five are Spain, Greece, Slovakia, Romania and Cyprus and their reasons are mix and so is their level of cooperation with Kosovo. Some of these countries, like Greece have opened diplomatic offices in Pristina, yet others like Cyprus are adamant in their opposition to recognize Kosovo, even after Serbia will do so, according to declaration from top foreign policy offices in the country.

This puts Kosovo in a precarious situation, but recognition waves have made Kosovo clearly a standout and distinct case, thus adding legitimacy for its secession and proclamation of independence. Thus, Kosovo is a sui generis case, not directly related to other national liberation movements across the world and whose legitimacy is based on precedents set by the other former Yugoslav republics whose secession was legitimized by Badinter Commission. The International Court of Justice duly recognized such legitimacy, thus paving the way for Kosovo to be considered as a legal member of world community.[18]

Kosovo has already joined the process of integration in the EU, thus opening negotiations for visa liberalization process after starting breaking ground with Serbia in negotiations led by EU and its chief foreign policy officer, former Higher Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Foreign Policy, Baroness Ashton. The same talks helped Serbia first to receive the candidate status in March 2012 and two years later, in January of 2014 to successfully open the negotiation chapters for full accession into EU. Kosovo trails Albania in its integration speed and such asymmetry may lead to potential friction in the present and future regarding free circulations of goods, services, labor and capital as well as restrictions vis-à-vis such goods and freedom of movement from third countries.

General views on Albania-Kosovo multifaceted relations

The commercial activity has not generally been much consistent between Albania and Kosovo. Also, a unified cultural market is emerging, marriages between citizens of both countries are happening etc. Same argument can be made about the unification of a cultural market, where the example of books, magazines, newspapers and TVs were read and watched simultaneously in both sides of the border are shared by many in this side and the other of the Albanian-Kosovar border.

On the other hand, there are many who share the thought that any potential unification between the two countries would be impossible. A recent survey has been published in Kosovo that provides detailed data on relations between Albania and Kosovo on some of the key issues. The survey was published by the Kosovo Foundation for Civil Society and the Foundation for Open Society in Albania. Regarding the question of whether they want to achieve national unity, 63 percent of respondents in Albania and 54 percent of respondents in Kosovo say they want unification. Citizens living in urban areas in Kosovo and Albania are mainly against national unity. If there was a referendum on unification, 75 percent of Albanians say they would vote in favor, versus 64 percent of Kosovars. But only 23 percent in Albania and 17 percent in Kosovo believe that this project can be implemented. It is also of interest that 88 percent of Kosovo Albanians say they have visited Albania, while only 31 percent of Albanians in Albania say they have gone to Kosovo. Albanians of Kosovo see security as the biggest problem in Albania. Sixty percent of them say they feel safe. Meanwhile, 85 percent of Albanians in Albania feel safe in Kosovo. Also, in terms of marriage, 75 percent of Albanians in Albania say they would have no problem marrying Kosovo Albanians, while slightly a bit over majority (56 percent) of Kosovo Albanians would have no problem marrying Albanians in Albania. Meanwhile, 65 percent of Albanians in Albania say they would marry someone from Western Europe, while only 19 percent of Kosovo’s citizens would, thus Albanians of Kosovo being much more conservatives in this regard. The same is relevant for religion, when a full 76 percent of Albanians have no problem marrying members of other religions, while in Kosovo only 13.5 percent are ready to marry someone of another religion.

In general, Kosovo Albanians are better informed about the leaders of Albania’s main institutions and their historical dates compared to Albanians in relation to the same issues in Kosovo. Also, Kosovo Albanians follow the Albanian media more than Albanians of Albania do. Respondents from both countries think that education is more developed in Albania than in Kosovo, while rule of law, welfare and sport are more developed in Kosovo than in Albania.[19]

On the other hand, there has been a lack of a coherent strategy from Albania`s foreign policy in the last two decades versus Kosovo and part of this are also political dissents in this side of the border and the other. However, Albania has generally tried to keep a moderate role that was conform international factors` stance. The lack of strategy was one the factors that had a negative impact when back in 2005 Albania asked for the same limited independence for Kosovo, which was something absurd coming from Albania.

Also, we have regularly witnessed lack of coordination of policies in education and other important fields, which makes any potential deepening of cooperation between the two countries hard to come by. Paradoxically on the other hand, we have observed a rising nationalist fervor in both sides of the border. On the other hand, we have had a successful strategy in infrastructure and not only in terms of roads, like the Nation`s Highway project, but also the energetic infrastructure etc.

Of importance is also the bottom-up perception, while figuring not enough in textbooks. But we have to keep in mind the general and overall weakness of the Albanian state and the fact that more than Albanians themselves; the foreigners are the ones that have given more thought to the Albanian unification process. Despite that, Kosovo and Albania have sent joint military troops in Afghanistan etc., is a signal that a growing cooperation between the two states also in military, security and foreign affairs is coming under the way, notwithstanding the fact the in the Homeland Security Strategy in Albania, Kosovo figures only in a single line. On the other hand, also in Kosovo`s strategy of 2020, Albania has figured peripherally. But also, Albania is to blame for a political class for lack of vision in regard to Kosovo, which in turn makes “Yugosphere” the only feasible geopolitical agreement. This last one of course excludes Albania. We have also had an inferiority problem that elites in Tirana and Pristina have and the complexity they show vis-à-vis foreigners and that is manifested among other things in Tirana using Kosovo rather than Kosova as official terminology.

Recent developments in deepening the cultural and educational relationship between the two countries are a step forward but still too little, too late. An example of that is the first meeting of Albania-Kosovo Committee which took place in May 22, 2019 in Tirana where it was commonly discussed about the educational texts for diaspora. This Committee is based on the bilateral agreement between Albania and Kosovo “For the common organization of the Albanian language and culture teaching in diaspora.”[20]

Trade between Albania and Kosovo

In general, the exports to Kosovo have experienced a significant increase of around 52% during the first 4 months of this year, while current barriers are calling into question the economic collaboration between the two countries. The Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Albania has already urged the government to remove barriers that endanger trade between Albania and Kosovo. According to its Chair, if measures are not taken as soon as possible, Kosovo will impose the same tariffs on Albanian businesses, which would hurt exports. Exports of products “Made in Albania” have declined in total, but trade with Kosovo has grown by about 100 million euro over the past 4 years.[21]

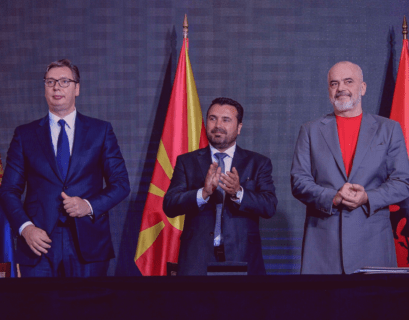

There are a lot of current trade obstacles in relations between the two countries that must be addressed before any pan-regional initiative such as the proclaimed Balkan Schengen, which for the moment is faced with much skepticism from Kosovar side, with an unprecedented consensus from its entire political class. Such common obstacles are for example the customs clearance procedures in Albania, payment of scanner, notarization of analysis, toll payments on the Nation’s Road, failure to take into account the invoice price by the Albanian Customs, implementation of the high excise rate for the beer sector, which increase the cost of production but also lower the level of competitiveness of Kosovo products in the Albanian market.

In a repeated manner the Kosovo businesses have requested inter alia “the removal of payment for scanner in the Republic of Albania for all Kosovo-Albania import-export trades; recognition of certification and sanitary gain analysis of all products subject to these tests and certificates; acceleration of customs procedures in dealing with trade and economic circulation between the two countries; to completely abolish the 22.5 euros toll prices for both countries’ trucks, as the same poses an obstacle to economic development and cooperation between the two countries, as well as full removal of all barriers including beer excise. For Albanian businesses, the main obstacles are the truck parking fees of 40 euros per day and the lack of phytosanitary certificates acknowledging.”[22]

Kosovo has often threatened reciprocal measures, such as introducing a 100% tax on products from Albania within two months if Tirana does not remove barriers to Kosovar exports of flour, beer and potatoes. The plans were revealed on May 22 of this year after trade representatives from Tirana and Pristina failed to agree on how problems related to the export of the three products could be solved. The two countries have been seeking to create a common market in several areas, for example by “uniting their electricity markets, building new road infrastructure and reducing mobile roaming tariffs. However, progress appears to have stalled on removing barriers to trade.”[23]

Trade tariffs that Albania applies in Kosovo are extremely high, even compared to other regional states. For example, in “a survey conducted by local think tank the GAP Institute among Kosovan businesspeople on the trade climate in the region, Albania was ranked second behind Serbia for the high trade barriers it applies to Kosovo. Trade barriers in Albania are considerably higher than those in fellow Balkan states Croatia, Montenegro and North Macedonia, found the report, based on data from Kosovo’s Ministry of Trade and Industry. Kosovo imposed 100% tariffs for Serbian and Bosnian products in November 2018 for political reasons. According to GAP’s research the tariffs have not resulted — as forecast by local officials — in stimulating local production, but in a reorienting of the country’s main sources of imports.”[24]

Even after the 100% tax on Serbian products that Haradinaj government imposed, the 37 million euros in products that Kosovo imported every month from Serbia have not been replaced with Albania’s imports. While the bulk of imports are substituted with Italian and German products, even regional countries such as Bulgaria have doubled it.[25] Whereas Albania, which was expected to be the main spoiler/winner of the Kosovo’s embargo on Serbian products has in fact lowered its share of exports. While Albania had exported 22 million euros in October of 2018, in October of 2019 the value has fallen to 19.7 million euros.[26]

ANALYSIS OF SHORT, MEDIUM- AND LONG-TERM RELATION BETWEEN ALBANIA AND KOSOVO

Potential Scenarios

The likely scenarios may be the following:

- Kosovo and Albania borders become gradually irrelevant as part of European Union if both are integrated at that stage.

- Albania and Kosovo are part of one of the following regional proposals (i.e. Balkan Mini-Schengen, Balkan Benelux, CEFTA etc.), but only one of them (most probably Albania) is part of EU by 2035.

- Albania and Kosovo realize a de facto unification before accession in the European Union.

- Albania and Kosovo operate as two functional countries without any projected unification of any kind, where Albania joins EU, with Kosovo still to conclude state-building process.

- Neither of the countries joins the European Union before 2035 while they are fully integrated in a regional bloc that achieves Customs Union by 2021 and Single Market by 2025. On the meantime they are caught in the newly proposed and (potentially) agreed Macron plan of “blocs”.

I argue here that the scenario most likely to happen in the next ten years period is the last scenario, while the scenario the most likely will develop in the next decade after that is the B scenario.

- Scenario A

In this scenario, Kosovo and Albania borders would become gradually irrelevant as part of the European Union if both are integrated at that stage. The potential period when this may happen, we assume to be no earlier than 2030. For Albania the prospect of membership, if due reforms are undertaken and laws properly implemented, thus fully constituting the rule of law, can be as early as 2022-2023, in Kosovo`s case even in best case scenario, the full accession cannot realistically happen before 2030.

In Albania, the main challenges and ‘homework’ are providing anti-corruption mechanisms, fighting the organized crime and money laundering, a fully functional public administration based on meritocracy and purged of party militants, property rights and reforming the justice system which is broadly perceived to be dysfunctional, politically biased and corrupted. In Kosovo, the challenges are even greater. Not only does Kosovo suffer by most of the aforementioned symptoms, but in addition it is not fully recognized even by EU member countries, where five countries (Greece, Cyprus, Spain, Slovakia and Romania) have so far refused to offer recognition. Also, Kosovo does not fully possess the elements of internal sovereignty, where Northern Mitrovica is outside effective control of Pristina government and structures such as UNMIK, KFOR and EULEX continue to limit the full prerogatives of a Kosovo state. Furthermore, Kosovo faces a high degree of danger from Islamic fundamentalism. According to philosophy professor Blerim Latifi and sociologist Ismail Hasani, it is the political and development crises which in tandem with poor quality in educational system create a habitat for political Islam to grow and endanger the perspective of Kosovo`s youth.[27]

From another perspective, Thaçi`s government and mainstream political spectrum is resisting well to nationalist pressures as the Economist Intelligence Unit of 2014 reports.[28] Parallel with this, the relations between Albania and Kosovo are getting stronger, although the authorities in both countries have distanced themselves from nationalists who call for “Greater Albania”. Also the report notes that the Socialist government in Tirana it is seen to be more reluctant in nationalist calls that their predecessors.[29]

However in long term perspective, the aforementioned scenario is the most probable one, since EU`s commitment to its Western Balkan “backyard”, is to leave no black holes behind. This EU commitment is despite short term policy approach that is embraced also by successful countries from the region, like Croatia which joined EU last year that have favored the “regatta principle”. This principle requires each country to progress toward integration at its own pace, thus replacing the “caravan principle” which professes the in-bloc concept of accession, thus forcing the more successful states to be on same par with laggards (Gogova & Radoslavova 2001).

- Scenario B

In this other scenario, Albania and Kosovo are part of one of the following regional forums: Balkan Union, Balkan Benelux, CEFTA etc., but only one of them, most probably Albania, is part of the EU in the next ten years or so. This is what actually is happening and the candidacy status of Albania that is waiting to open the negotiation chapters for full accession is promising. This seems to be the most realistic term scenario given the actual trends and potential developments. Such trajectories would make the relation between the two countries asymmetric in the short-term and potentially medium period, given rise to potential frictions or complaints from various interest and pressure groups from both sides.

The present lack of political will as well as vision and leadership is also reflected in an economic asymmetry. aMong other things we lack common institutions. Also, we are in need of improvement of monitoring system to improve efficacy, which should not be done by governments, but by the experts. The full removal of border obstacles can be the first step in this direction. Before a Balkanic Schengen or Western Balkans Customs Union, we need an Albania-Kosovo Customs Union as the first step in this regard. Developing infrastructure will make borders invisible and enables growth of levels of trade. A tested example of that is Kosovo highway which increased the trade volume to 23% up from 4% before the highway construction. Because Balkan Peninsula has little resemblance to other European peninsulas, we tend to produce more or less same products and have fragmented markets which makes both Albania and Kosovo less competitive in international markets. It seem that the only remedy is a potential unification which for most observers though it should only come de facto after integration of both units in the European Union.

The level of trade is also reflected in the number of businesses of both states in the territory of the other. There are only 380 Kosovar businesses in Albania, some of which are with mixed capital and a bit over 500 of Albanian companies in Kosovo, which is a testimony of the market operating under its full potential. Although situation looks grim, it looks that new initiatives are undertaken by both governments Rama and Thaçi to increase trade volume and deepen the already friendly partnership. Such initiatives range from energy matters to facilitations of workers from respective countries to freely work and pay social security dues in either country which will later go their respective pension schemes, although these new policy initiatives need still to be implemented in order to go from words to deeds. Other areas of strong cooperation are those of police troops where an agreement has been reached that Kosovar patrols can operate within Albania`s territory and vice-versa during the summer when the holidays reach their peak. Other areas include unification of textbooks, a primary for both countries, unification of curricula etc.

Even in those regional organizations where Kosovo is extended invitation, it is done so with an accompanying asterisk, although not a footnote as it was previously suggested. This is a step forward but Kosovo is still not allowed to use state symbols like state flag and Serbian officials are required to ask for UNMIK presence (Jovanović and Karadaku 2012). It is not sure what the situation will be from now onwards since Kosovo has recently made the formal request for UNMIK to withdraw its mission.

- Scenario C

Albania and Kosovo realize de facto unification before accession in EU. This is a rather unlikely scenario, although it is cheerfully claimed by nationalists in both sides of the border. Amongst the supporters of such view one can find mainstream political parties like Vetvendosja in Kosovo (left wing nationalist party) to PDIU in Albania (center right nationalist party in Albania) to the parties on the fringe of the political spectrum like Natural List and Aleanca Kuqezi in Albania and Partia e Drejtesise in Kosovo (which is part of the pre-election and still ongoing governing coalition) etc. Regarding Vetvendosja, as an analyst from Albania has put it recently in an interview for the daily Zëri in Kosovo: “[t]o be fair, they [Vetvendosja] have proposed one thing, the old idea of national unification as a metaphor of Albanian panacea. The medicine that cures everything is national unity in one flag, according to Albin” (Lita 2014). Although Lita continues by arguing that Albin Kurti so far has not found an ally for his political project in Kosovo or Albania, in fact the examples above, like PDIU, a parliamentarian party and AK in Albania, or some small parties in the fringes of political life in Kosovo testify for the opposite.

Not only political parties are supporters of this view. Evidence presented above from recent polls and surveys also show a surprisingly high support for unification between the two countries, although slightly less so when asked to assess how realistic they thought it would be. Another important category is the nationalizing intellectuals, who have consistently asked for a rapid and successful unification “between the two parts of the same trunk”. Such prominent ones include in their ranks, the likes of Rexhep Qosja or Adem Demaçi amongst Kosovo Albanians and several intellectuals and prominent writers among the Albania`s counterpart.

- Scenario D

Albania and Kosovo operate as two functional countries without any projected unification of any kind, where Albania joins EU, with Kosovo still to conclude state-building process. This is the prospect for the next 10-15 years in my view. I expect Albania to fulfill the integration process and finally join European Union by 2022-2023, while for Kosovo the perspective can go as far as in the range of 2035-2040, unless there is a change of plans and the region is integrated in block.

This scenario seems to be happening as we write, since Albania has already received the candidacy status and is waiting to open the negotiation chapters for full accession anytime now. The exact period is not yet settled but Albania has already received a list of ‘homework’ to be completed, which include the reforms to combat organized crime and corruption, de-politicization of public administration, the reform in the legal system, finding a property rights long-term solution and political consensus that would finally stabilize the country and make it more prone to democratization.

However, as it was made clear recently in the Berlin Summit where the leaders of the Western Balkans took place, there will not be further accession in the region for the next five years. In other words, no candidate country (Serbia, Albania, Montenegro and Macedonia) or Kosovo and Bosnia- Herzegovina can expect to join European Union at least until 2019. This is realistic period but countries like Kosovo and Bosnia-Herzegovina, due to recognition issues or state-building and other functional problems have to realistically wait for another decade after the other four will most probably have joined.

- Scenario E

While France seemed to have been retired years ago from the Balkans and the area appears to be not crucial for its diplomacy, it has recently re-emerged with four key objectives in the region:

- Redesigning the enlargement procedure by prioritizing establishment of the rule of law and promoting governments sincerely attached to the EU and its values.

- Fighting illiberalism in the Balkans as anywhere else in Europe.

- Having enough credibility to re-emerge as a serious actor in the region in the frame of its “strategy for the Balkans”

- Actively promoting and assisting in the resolution of the Serbia-Kosovo issue.[30]

The French plan consists basically in these four points. The last point seemed tricky because indirectly involves also the relationship of Albania and Kosovo as well as the recent diplomatic engagement of Albania and Serbia in both bilateral and multilateral formats.

All in all, Paris renewed approach is considered to be based on four main principles: gradual association; stringent conditions; tangible benefits; reversibility.[31] It has opened up much debate and the 7 blocs it has proposed for the Western Balkan candidate countries to be able to be eligible for full accession have widely been considered from these countries as a road leading to nowhere.

The seven stages from rule of law to foreign affairs that include internal markets, agriculture etc.,[32] sets no date for full membership, no guaranteed success for these countries long considered EU’s backyard and no promises of “carrots”, while the “sticks” become more visible. In this context, neither of these countries, including Kosovo and Albania joins the European Union before 2035, while they are fully integrated in a regional bloc that may try to achieve Customs Union by 2021 and Single Market among themselves by 2025.

Conclusion

The question of borders dissolution after both Kosovo and Albania will finally join the European Union, assumes an explicit automaticity, which does not take into consideration the various hindrances to this process. Albin Kurti, the prime minister-designate, has often repeated that membership in the European Union does not dissolve borders but hardens them. In other words, this implies that the Albanians of Kosovo and Albania should seek unification before and not after joining EU.

In terms of the objective factors which can present a hindrance of a facilitating factor toward potential unification of friction between the two countries before or after entrance in EU, which most probably will be based on individual merits and structural reforms, we can list some important factors. One is the economic size, which is more than twice in Albania (with 13.8 billion Euros) vis-à-vis Kosovo with less than seven billion euros. Although this roughly corresponds to the number of total population that is almost double in Albania or the territorial scope which is almost three times as big in Albania than in Kosovo, still asymmetries can turn easily into fears which prevent further integration between themselves. But on the other hand, they can equally turn into opportunities if leaders of both countries recognize that even the merger of the two states still is a small step in creating the proper consumer demand and attracting enough foreign direct investment because the size of the market remains small in comparative terms. Still in that case if would be more attractive than current one and it will probably be an incentive to move things forward, at least by seeking to integrate financial markets and find solutions that can culminate in a customs union or even reach the stage of full economic integration.

On the other hand, how motivated are the fears of a “Greater Albania,” which basically presupposes the unification of Kosovo with Albania? Florian Bieber in an article written sometimes ago for Sudeosteuropa writes inter alia: “[t]he idea of a “Greater Serbia” and “Natural Albania” (as its proponents often call it) exist. Yet, these are irrelevant ideas. The Red and Black Alliance in Albania got just a little more than 10,000 votes in parliamentary elections in 2013, the only party supporting this agenda openly” (Bieber 2014). This has been true for the entire post-communist period and simply there have not been any legacies from the past for a so-called Greater Albania, so these fears are simply not motivated and not backed up empirically.

Quite on the contrary, I believe that any projection for a de jure unification prior to full accession of the two countries (Albania and Kosovo) in the European Union, which might take decades, is simply not realistic and impossible to materialize and not only because of constitutional obstacles and opposition of international actors, but also from resistance by the mainstream political leaders in both countries which may see any potential unification as a threat to their personal power. Whereas, de facto unification on the other hand, which may culminate in either a free market zone, a custom union or a full integrated economic zone, before or after full accession in EU, can be realized to some degree and with some success, depending on the political willingness and geopolitical circumstances. Yet it can be only between Albania and Kosovo or otherwise it can be in a form of a regional organization, such as the idea of Balkan Benelux, which includes also FYROM and Montenegro in a projected scenario.

All in all, in this article I analyzed the projected scenarios of development of relations between Albania and Kosovo, how they have evolved from Kosovo`s proclamation of independence, how they are now and what are the chances for each potential scenario in the short and medium terms. Of course, I also briefly considered the historical, cultural, and political history of the past in the relations between Albania and Kosovo, in order to draw substantial and well-based inferences for the immediate future. It is my contention that European integration path is slightly different for the two countries, with Albania having more chances to join prior to Kosovo the EU and this will further conditionalize the former`s attitude toward the latter in economic, social, cultural, and political areas of cooperation. The potential unification between two halves following the German model after the Iron Curtain, which has been the ultimate goal of many in both sides of borders, is difficult to be concretized outside the framework of European accession of countries, where borders would become irrelevant and a full economic integration fully achieved.

References

Bieber, Florian. 2014. “Greater Serbia and Greater Albania do not exist: The myth of bad Serb-Albanian relations.” Balkans in Europe Policy Blog. Retrieved Nov 8, 2014 from:

http://www.suedosteuropa.uni-graz.at/biepag/node/113

Coakley, J., ed. 1992. The Social Origins of Nationalist Movements: The Contemporary West European Experience. London: SAGE Publications.

Gogova,Ivana&Branimira Radoslavova. 2001. “Croatia on the Road to EU Membership,” Central Europe Review, 3 (14).

Kalemaj, Ilir. 2014. Contested Borders: Territorialization of National Identity and Shifts of “Imagined Geographies” in Albania. Peter Lang Ltd. Oxford 2014.

Kalemaj, Ilir. 2013. The Typologies of International Recognition (Kosovo as a sui generis case). [Tipologjitë e njohjes ndërkombëtare (Kosova si një rast sui generis)]. Studime Juridike, publication of Faculty of Law, Tirana University (peer reviewed).

Krasniqi, Afrim. 2014. Raporte Elitare vs Raporte Militante mes Shqiptareve. Shqiptarja daily. 14.08. See for full article: http://www.shqiptarja.com/analiza/2709/raporte-elitare-vs-raporte-militante-mes-shqiptareve-239173.html

Ivanovic, Jovana & Linda Karadaku. “Serbia to participate with Kosovo at regional gatherings.” Southeast European Times. 10/09/12. http://www.setimes.com/cocoon/setimes/xhtml/en_GB/features/setimes/features/2012/09/10/feature-01

Lynggaard, Kennet. 2012. “Discursive Institutional Analytical Strategies.” Research Design in European Studies: Establishing Causality in Europeanization, (4)15.

Maliqi, Shkelzen. 2014. “Shkëlzen Maliqi këshilltar i kryeministrit Edi Rama për rajonin, shprehet se tendenca e një kombi kosovar është tendencë absurde.” Gazeta Mapo, 23 Gusht. Tirane.

Pedrazzi, Nicola. 2014. “A Pope in a symbolic land: Albania.” Osservatorio Balcani e Caucaso.

Spahiu, Nexhmedin. 2014. “Kombi Kosovar është definuar para 20 viteve, ate nuk mund ta definojë Shkelzen Maliqi sot”. BotaShqiptare, August 25. See for full link:

Zheji, Artur. Do ta provojne edhe gjermanet. Gazeta Mapo. 23.08.1014. See full article at http://mapo.al/2014/08/ta-provojne-edhe-gjermanet/

Websites

[1] UNHCR (1999), Global Report, p.321, http://www.unhcr.org/3e2d4d50d.html

[2] See for a detailed view the coverage in international press, including prestigious media such as CNN, BBC, Washington Post etc. The following exchange is quoted form Reuters: http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/11/10/us-serbia-albania-kosovo-idUSKCN0IU16W20141110

[3]http://www.top-channel.tv/new/lajme/artikull.php?id=287595#rel

[4]http://www.gazetatema.net/web/2014/10/31/minxhozi-rama-do-te-shkoje-edhe-ne-presheve-nuk-kemi-ne-axhende-shqiperine-e-madhe/

[5]Ibid

[6] See: http://www.balkan-monitor.eu/files/Gallup_Balkan_Monitor-Focus_On_Kosovo_Independence.pdf

[7] Third largest party represented in the parliament.

[8] A group of 12 deputes representing four parliamentarian parties petitioned the Parliament with a unification request with Albania, though fell short gathering signatures amongst other colleagues. The goal of the initiators in the first phase was to draw the attention of international community and to achieve the end of negotiation with Belgrade. See for details: http://www.alsat-m.tv/index.php/lajme/rajoni/116664.html

[9]http://www.gazetatema.net/web/2014/05/07/hiqen-lejet-e-punes-per-qytetaret-e-kosoves-dhe-lugines-se-presheves/

[10]http://inserbia.info/today/2014/11/mogherini-independent-probe-for-eulex/

[11]http://www.un.org/en/peacekeeping/missions/unmik/mandate.shtml

[12]http://www.kosovocompromise.com/cms/item/topic/en.html?view=story&id=1571

[13] Ibid

[14] The examples are various but we can briefly mention here the role played by the American ambassador in breaking the deal to elect Ahtifete Jahjaga as the President, following the verdict of the Supreme Court that declared the invalidity of the process that had elected Behgjet Pacolli. Another testimony of strong American presence is Bondsteel base, the largest in Balkans and different pronouncements on domestic political affairs in Kosovo of various American ambassadors.

[15]http://www.gazetaexpress.com/lajme/panariti-ska-barriera-per-miellin-kosovar-qe-ploteson-standardet-48693/

[16] Such trade wars include but are not limited to potato and honey, cement and milk. See for a detailed view: http://www.lajmeonline.net/en/commercial-returns-kosovo-war-shqiperi/

[17] By comparison Palestine is recognized by circa 135 countries and still is far from being legitimately accepted in international organizations or other venues and its independence fiercely opposed not only by Israel, but also USA and several major European countries.

[18] See for a detailed view on this Kalemaj 2013.

[19] https://www.55news.al/aktualitet/item/229735-shqiptaret-e-duan-bashkimin-sondazh-per-raportet-shqiperi-kosove

[20]http://qbd.gov.al/mbledhja-e-pare-e-komisionit-te-perbashket-shqiperi-kosove-per-miratimin-e-teksteve-mesimore-per-diasporen-2/

[21] https://www.oranews.tv/article/kosovo-albania-trade

[22] Albania-Kosovo trade dispute continues. http://www.tiranatimes.com/?p=142492

[23] Kosovo considers extending 100% tariffs to Albanian products. https://www.intellinews.com/kosovo-considers-extending-100-tariffs-to-albanian-products-161640/

[24] Ibid

[25] From 6 million to 13 million euros in Bulgaria’s case. See for more: “Kush i zevendesoi produktet e Serbise ne Kosove?” INFOKUS, 25 Nov. 2019.

[26] Ibid

[27]http://www.gazetatema.net/web/2014/08/13/latifi-mungesa-e-cilesise-ne-arsim-nje-nga-arsyet-e-radikalizmit-islamik/

[28]http://country.eiu.com/albania

[29] Ibid

[30]https://atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/by-blocking-enlargement-decision-macron-undercuts-frances-balkan-goals/

[31] https://www.politico.eu/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/Enlargement-nonpaper.pdf

[32] https://europeanwesternbalkans.com/2019/11/18/seven-stages-of-eu-accession-this-is-how-france-would-reform-the-process/