LEDION KRISAFI, Ph.D

Abstract: In general, in the debates on foreign policy in Albania, the relations with North Macedonia are less mentioned and discussed compared with those with Greece, Kosovo and Serbia. But these relations are as delicate and important as the other. In the relations with North Macedonia, Albania has to maintain a delicate balance between the support for North Macedonia’s territorial integrity and its Euro-Atlantic integration processes and on the other hand the support for the Albanian population in the neighboring country without seeming to interfere in the internal relations of another country. In a certain measure, Albania has largely succeeded in this attempt in the last three decades, but also it has done it by sacrificing a little its national interests. This paper begins at this point to describe and analyze the developments of the last years, especially since 2016 and after the coming to power of Zoran Zaev, in whose electoral success the Albanian government had its share. At the same time in this paper will be analyzed the economic relations between the two countries. They are both part of CEFTA2006, but this has failed to elevate these relations in another level. The reasons for this will be analyzed in this paper. Also, it will be analyzed the perceptions of North Macedonia in the Albanian public and the role that Albania should play for its compatriots beyond the border. In general, the paper will try to give a comprehensive view of the current situation in the political and economic relations between the two countries. At the same time, it looks to the future of these relations by giving recommendations on what could be improved.

Historical Background

Any discussion of the bilateral relations of the states in the Balkans should start with history. In the case of the relations between Albania and North Macedonia, knowing the history not only of these relations, but the history of the region is important to understand the problems of today and to try to predict the developments of the future.

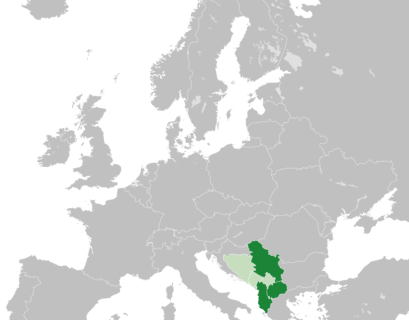

Before the First Balkan War in October 1912, Macedonia was a geographical name depicting a large territory that included approximately the Ottoman vilayets of Monastir and Salonika. It was a geographical description of territories that today are part of Albania, Greece, Bulgaria and North Macedonia. At that time the northwestern of North Macedonia, including the capital of Skopje and the second largest city of Kumanovo were not part of the geographical name of ‘’Macedonia’’.[1] This part of the territory was included in the Kosovo vilayet. Geographically and demographically, this part of the present North Macedonia was a continuation of the south-eastern part of Kosovo.

The population of this geographical region was diverse and in many regions very difficult to divide one ethnic group from the other. In general lines, in the western part this region was inhabited by Albanians, in the central and eastern part mainly by Bulgarians, as the Slavic population of Macedonia was called at that time, and in the south mainly by Greeks, Bulgarians and Turks.[2]

After 1918, the part of Macedonia that was conquered and incorporated into Serbia as a result of the Balkan wars became part of the newly formed Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes and later of Yugoslavia. But from 1918 to 1941 when Yugoslavia was conquered and dismembered by Nazi Germany, the name ‘’Macedonia’’ was not used in any of the administrative divisions of the country. From 1918 to 1922, the territory that now constitutes North Macedonia was called Southern Serbia, which was part of the administrative division of Serbia inside the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. In 1929 with the new administrative division of Yugoslavia, was created the Vardar Banovina, which encompassed the present territory of North Macedonia and territory in the south-east of the present state of Serbia.[3] After the Second World War, Macedonia became a constitutive republic inside the Federal Socialist Republic of Yugoslavia. This was the first time since 1918 that the name ‘Macedonia’ was used officially to depict the territory of the present state of North Macedonia and it was the first time since at least the middle of the XIXth century that the name ‘Macedonia’ was used to describe the northern part of the present North Macedonia, including Skopje, Kumanovo, Tetovo and Gostivar.

This discussion of the name ‘Macedonia’ and how it came to describe the territory of the present state of North Macedonia, is very important to understand the Albanian population inside the country, its development and relation with the other parts of the territory and with the Slavic Macedonian population.

In the new People’s Republic of Macedonia, Albanians were treated as a national minority and in many cases they were forced to declare as Turks and to be sent to Turkey.[4] After the 1953 ‘’gentleman agreement’’ between Yugoslavia and Turkey, which was a continuation of the 1935 agreement for the repatriation of Turks and Muslims in general from Yugoslavia to Turkey, in Macedonia thousands of Albanians declared themselves to be Turks in order to go to Turkey. In the 1953 census in Yugoslavia the number of people declaring themselves Turks in Kosovo and Macedonia grew considerably. At the time there was intensive propaganda from the Yugoslav and the Turkish side for the Muslims of Yugoslavia regardless of their ethnicity to be declared Turks.[5]

Since the disintegration of Yugoslavia and Macedonia’s independence in 1991, Albanians’ demands for more rights and an equal participation in the state institutions have grown more assertive, culminating in the 2001 civil war and the subsequent Ohrid agreement. This agreement laid out the groundwork for the transformation of the Albanians’ position in North Macedonia. Though the Ohrid agreement has not been totally implemented, Albanians’ position in North Macedonia has changed compared with the beginning of the 90s.

In the decade of Gruevski government, the Albanian political parties were continuously part of the government, but the Gruevski governments began a huge program of buildings in Skopje with the purpose of connecting the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia to the ancient heritage of Ancient Macedonia. This program left little room for Albanians and it further worsened the relations with Greece and consequently stalled Macedonia’s NATO and EU integration prospects.

The Albanian political parties, part of the Gruevski governments, weren’t able to stop this policy that went against their interests. Even though the Albanians’ situation improved slightly during that time, the Macedonian state went backwards not only in the relations with its neighbors, but also in the democratic processes inside the country.

During this period in North Macedonia, there was a ‘’silent agreement’’ between the Macedonian and Albanian political groups, as a consequence of which there was practical division of Macedonia. The Albanian political parties would be in charge with the Albanian population and Albanian issues, while the Macedonian political parties with the Macedonians and their problems. This pattern was somehow broken during the 2016 Parliamentary elections, when it was reported that large numbers of Albanians voted for the Macedonian political party LSDM.

Albania’s delicate balance with North Macedonia

In the last three decades Albania’s policy towards North Macedonia has been constant. At the time of the independence of the then-FYROM in 1991, Greece opposed the use of the name ‘’Macedonia’’ and contested the appropriation from the new state of the Greek historical symbols like Alexander the Great and the Vergina Sun; while Bulgaria also had its reservation regarding the language and the inhabitants, but from all the then-FYROM’s neighbors Albania was the only one who recognized the new state without any reservation or conditions, despite the fact that the new state had a considerable Albanian population, which at the time was severely hampered in its rights.

In the last three decades Albania has constantly supported North Macedonia’s EU integration process and NATO membership process, the process for a solution of the name dispute with Greece and it has engaged in supporting and helping the Albanians in that country. Continually during this period Albania has emphasized the fact that the security and inviolability of North Macedonia’s borders is one of the cornerstones of the peace and stability in the region. The historical past of the region and especially that of the broader region under the name of ‘’Macedonia’’ has shown that almost all the countries in region from Albania to Serbia, Greece and Bulgaria would be involved in a crisis in North Macedonia. For this reason, Albania has continually supported North Macedonia’s EU and NATO integration because it would secure its internal and external peace and security.

In this history of almost three decades the year 2017 signifies a breach of this policy. At the time, the Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama gathered in Tirana all the main political representatives of the Albanian community in North Macedonia. The result of the meeting was a series of demands, which in general were the same demands that Albanians had presented in the last two decades for more rights, more presence in state institutions, the languages law, etc. New in that case was the fact that they came jointly from all the Albanian political parties in North Macedonia and most peculiarly because they came from Tirana. Also it was the first time since North Macedonia’s independence from Yugoslavia that an Albanian government not only tried to influence the voting patterns of the Albanians in North Macedonia, but it was positioned openly on the favor of a major party in North Macedonia before the parliamentary elections. The gathering in Tirana and the rhetoric which followed it were openly in favor of Zoran Zaev’s LSDM and againts Gruevski’s VMRO-DPMNE.

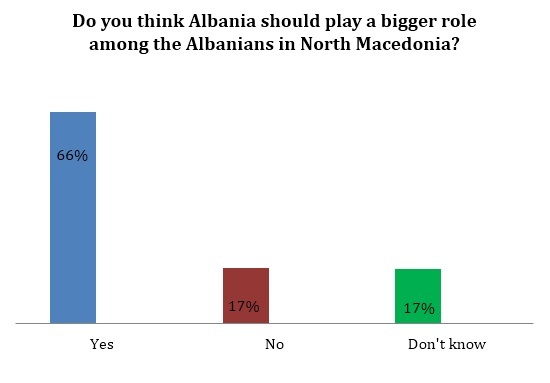

In relation to North Macedonia, Albania is in a peculiar position. Because of the large Albanian population in the eastern neighbor Albania has to act in a fragile balance between helping and supporting the Albanians in North Macedonia and not seeming to interfere in the internal affairs of another country. Most of the Albanian citizens say that Albania should have a bigger role and presence among the Albanians in North Macedonia and almost 70% of them saying that this bigger role is good for the Albanians there[6].

At that time, Macedonia’s president Gjorgje Ivanov said that the demands of Albanians for more constitutional rights, which were expressed in written form in a document that was called ‘’Tirana Platform’’, threatened Macedonia’s existence and sovereignty. According to Ivanov, ‘’The platform implies changes to the constitution of the Republic of Macedonia that would jeopardize the unitary character of the state’’. [7] In the same vein, after the ‘’Tirana platform’’ Russia accused NATO, EU and Albania of trying to install a pro-Albanian government in Macedonia. “With active cooperation of the EU and NATO officials, an ‘Albanian platform’ created in Tirana, in the office of the (Albanian) prime minister, is being imposed on Macedonians, said a statement of Russia’s Foreign Ministry at the time.[8]

In this case, while Tirana’s purpose was to create cohesion among Albanian parties in Macedonia regarding their demands, in view of the fact that the lack of cohesion among Albanians is constantly lamented, the final product was interpreted as an ‘’attack’’ against another country’s sovereignty. The cohesion sought by the ‘’Tirana Platform’’ would had maximized the Albanian votes in Macedonia, as the Macedonian electoral system is such that more fragmented the Albanian political parties, less MPs they get.[9] As such Tirana’s attempt was in principle and purpose good, but in manner bad.

Even though the new LSDM-majority government of Zoran Zaev was created in coalition with several Albanian political parties and the government has started to implement some of Albanians’ demands, the ‘’Tirana Platform’’ may have damaged Albania’s relations with the VMRO-DPMNE party, which is now in opposition. This fact may threaten the good relations between Albania and North Macedonia in a future VMRO-DPMNE government. At the same time, the ‘’Tirana Platform’’ may have created the impression that the Albanian state prefers the LSDM party in North Macedonia against the other large Macedonian party.

This point was emphasized by the former Prime Minister Nikola Gruevski after the elections of December 2016, when he said that ‘’a serious external influence has weakened the VMRO-DPMNE position. Diverse factors have worked in order to help LSDM’’.[10] In this view, the ‘’Tirana Platform’’ created unintentionally a situation unknown in the Albania-North Macedonia relations of the last two decades.

But on the other hand, Albania can’t stand as a spectator in the internal developments of North Macedonia. Inter-ethnic problems there could pose security challenges in Albania and Kosovo also. In this view, Albania’s relations with North Macedonia are the most delicate in the region, which need special care to balance between national interest and intervention in the internal affairs of another country. In the future this situation for Albania will become easier, because the demographic situation in North Macedonia and political changes will ensure that Albanians there will be more present in the state institutions and will need less the intervention or the presence of Albania.

Also, 2017 was a crucial year because after the electoral triumph and the new government of Zoran Zaev, there was the attempt to increase the level of the relations with Albania. Ideologically Zaev and the Albanian Prime Minister Rama stand on the same left-wing camp, also both are constistenly pro-EU and NATO in the case of Macedonia, which was not the case with the Gruevski government. These aspects and the fact that Zaev took a considerable vote from the Albanian electorate in Macedonia, made possible the prospect of a change. This change of policy was reflected in the first inter-government meeting between the Albanian and Macedonian governments in Pogradec in December 2017. The meeting was important also in the fact that it tried to establish a long-term strategy for raising the level of relations between the two countries. This includes the building of railway and highway connections between Albania and Macedonia, the functioning of the One-Stop-Shop model of customs, etc.[11]

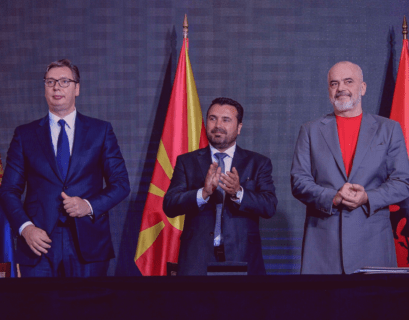

The mini-Schengen initiative in 2019 was a step further in the relations between Albania and North Macedonia, even though certain parts of mini-Schengen have been functioning in years. For example, citizens of Albania and North Macedonia could travel in each other’s countries with ID cards since 2012 and the free trade is already covered by CEFTA2006. The major change brought by the mini-Schengen is in the labor market. It will be much easier for companies in Albania, North Macedonia and Serbia to hire labor in from each other’s countries.

Economic relations

Since 2006 Albania and North Macedonia are part of CEFTA, the Central European Free Trade Agreement (CEFTA). Prior to CEFTA, Albania and the then-FYROM had signed a bilateral trade agreement.[12] CEFTA2006 entered into force on 1 May 2007 and in the first year there was a large increase in the trade volume between Albania and CEFTA countries. In CEFTA’s first year, there was a considerable increase in Albania’s exports to Macedonia, from 10 million Euros in 2006 to 17.7 million Euros in 2007. Also there was a big increase in imports from Macedonia, from 38.8 million Euros in 2006 to 59.1 million.[13]

Albania’s trade relations with North Macedonia after the signing of CEFTA have been fluctuating from year to year, decreasing and increasing. After 2010, Albania’s imports from Macedonia had grown compared with 2009 and 2010, but they had not reached again the value in 2008. The values for the six years after 2010 had been almost the same. In the last 3 years, 2014, 2015 and 2016, imports from Macedonia had de- creased. They were 63.3 million Euros in 2011, but they decreased to 56.5 million Euros in 2016. This was the third consecutive decrease. In 2014, they were 59.6 million Euros and in 2015, 61.3 million Euros. Compared with 2008, which was the year with the highest imports from North Macedonia, Albania’s imports from Macedonia in 2016 have decreased by 28.2%. A different picture emerges from Albania’s exports to Macedonia. While in imports there have been a considerable decrease in the last years, especially when compared with the best year 2008, Albania’s export to Macedonia have increased steadily every year. In 2015 and 2016, they reached the highest level in the last two decades, with 45.9 and 46.7 million Euros respectively.[14] This trend has continued even in the years 2017 and 2018 when Albania’s exports to North Macedonia have continued to increase and the imports have increased slightly. Despite the developments from CEFTA and Albania’s bigger GDP than North Macedonia’s, Albania has continously had negative trade balance, which almost went temporarely to parity in 2017.

The largest Albania’s imports from North Macedonia and the largest Albania’s exports to North Macedonia in the last years has been steel and its by-products. Albania’s second most exported items to North Macedonia is cement and lime and in the third place are vegetables.

Since March 2012 Albania and North Macedonia have talked about creating an integrated border crossing at Qafë-Thanë, with talks intensified in the last two year since Zaev’s electoral victory, but until now it hasn’t been done and all the deadlines for its implementation has been passed. On the other hand, North Macedonia has done an integrated border crossing with Serbia.[15] An integrated border crossing between Albania and North Macedonia would have facilitated greatly the trade between them.

There are four main problems in the economic relations. First, even though Albania and North Macedonia are part of CEFTA, in many cases their trade is not really free. In the last years there have been several cases of North Macedonia blocking Albanian products from entering its market.[16][17]

Second, it is the weak internal markets both in Albania and North Macedonia and the weak producing capacities of both countries. Most of the foreign companies that have invested and are producing in North Macedonia aim to reach their home country or the EU market and not neighboring countries. This shows that foreign investments in both countries don’t add much to the trade between them. Also most of the trade between Albania and North Macedonia is in raw materials and fruits and vegetables, which shows the two countries’ limited producing and manufacturing capacities.

Three, historical economic patterns that is difficult to change even with a free trade agreement. Most of North Macedonia’s trade is with the countries of former Yugoslavia, while Albania’s trade is mostly with Italy and Greece.[18] The same thing happens with the other former Yugoslav countries.

Four, lack of infrastructure connections between the two countries is a major problem. There is no rail connection and the roads are in poor condition, which makes it easier for the two countries to be connected by road through Kosovo, but which doesn’t help trade. The ‘’Rruga e Arbrit’’ which is being constructed is expected to ameliorate somehow the situation, especially as it will connect some of the main minerary regions of Albania directly with North Macedonia, boosting their transport capacities.

North Macedonia in the Albanian public

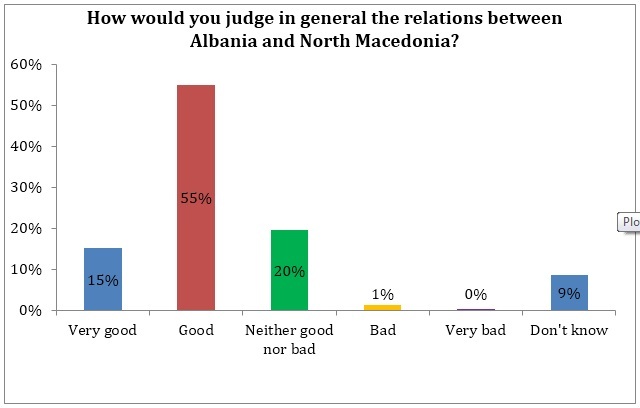

Most of the Albanian public regard the current relations with North Macedonia as good or very good, 55 and 15% respectively, while only 1% of the population thinks that relations with North Macedonia are bad with another 20% saying that they are normal, neither bad nor good[19].

The approximately same answers are also for the relations between the governments of the two countries and the relations between the citizens of the two countries. The absolute majority of Albanians say that relations in the governmental level or the citizens level are good, very good or normal. In the three cases the percentage of those declaring bad or very bad is very small, in the 1 to 4%. This attitude mirrors the overall relations between Albania and North Macedonia in the last three decades, where the two countries have had no open issues and have mainly refrained for using harsh words against each other, which has not been the case with Albania’s relations with its southern neighbor.

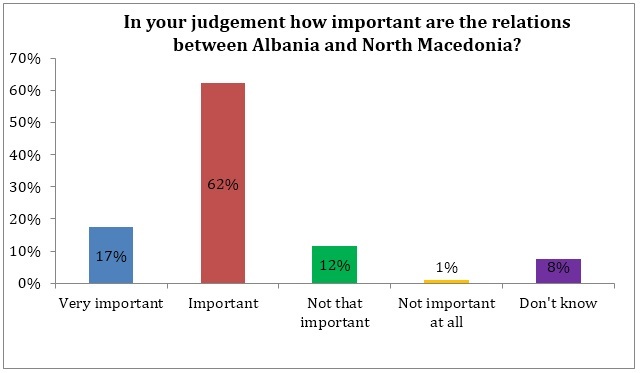

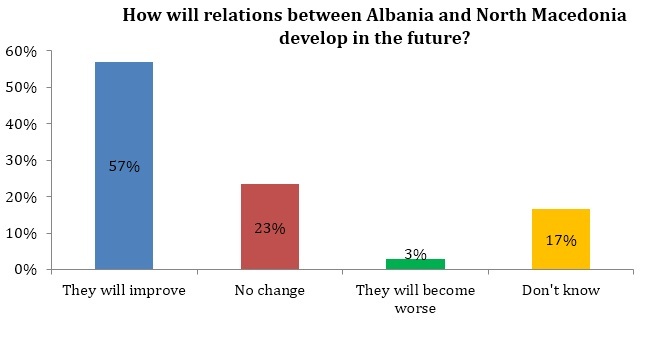

The Albanian public is also optimistic about the future relations. 62% of the respondents consider the relations between the two countries as important and another 17% as very important. At the same time, the majority of the respondents, respectively 57% think that the relations will improve in the future, while only 3% saying that they will be worse[20].

Most of the respondents say that the focus on economic relations, respectively 42%, while another 29% saying that the focus should be on political issues. Only 0.4% of the respondents say that the focus should be on security issues, mirroring the general perception of good relations between the two countries and the lack of visible threats from the eastern neighbor.

Also the absolute majority of the respondents support Albania’s policy of supporting North Macedonia’s NATO membership, with 81% in favor of it.

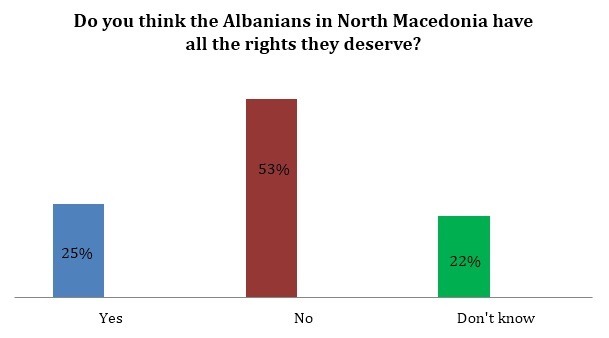

When it comes to the position of the Albanians inside North Macedonia, the number change. Most of the Albanians think that their co-nationals in North Macedonia don’t have the rights they deserve.

Also, compared with the other regional countries, Albanians seem to know more about North Macedonia and to have traveled there more than in Serbia or Montenegro.

The present and the future

The grouping together of North Macedonia and Albania in their EU integration process may have created certain animosity in the political circles in North Macedonia, especially since there was a perception that North Macedonia was better placed than Albania to open the accession negotiations with EU and it was ‘burned’ because of Albania. This was not the case, but this situation doesn’t help the relations between the two countries. Nikola Dimitrov, North Macedonia’s Foreign Minister called for the decoupling of North Macedonia and Albania. ‘’One is definitely better and more than none’’, said Dimitrov.[21]

But this situation hasn’t prevented Albania and North Macedonia to continue their collaboration by being part with Serbia in the so called mini-Schengen. Although Albania and North Macedonia have signed the agreement on free movement of their respective citizens only with ID cards since 2012[22], this initiative is nevertheless an attempt to increase the level of relations between the two countries, which has been the case in the last two years.

In the near future, the most problematic scenario would be a convicting victory of VMRO-DPMNE in the preliminary elections in April 2020. Because of the perceived interference from the Albanian government in the last two years in favor of the LSDM and Zoran Zaev and the clear position of the Albanian government in favor of policies in North Macedonia that were not supported by the opposition, there is the risk that relations between the two countries may experience a period of distancing and frost in the case of a convicting victory for the opposition.

This possibility could be alleviated if the European Union begins soon the accession negotiations with both countries. In this case Albania and North Macedonia will concentrate their focus and energies in their respective EU integration processes and will leave behind all possible bitterness of the last years. Also the opening of accession negotiations with EU will diminish the possibilities of Albania for interfering in behalf of the Albanian community in North Macedonia, because their position and their demands and rights will have to be part of the negotiations.

But the failure of the opening of EU negotiations should not prevent the two countries from working together and having better relations, despite which Party is in power, because national interests of the two countries go beyond the government of the moment.

In the economic relations, Albania and North Macedonia have made little progress in the last years. They should work more towards a full implementation of the rules of CEFTA; also they should consider opening more of their markets to companies and capital from each-other. There are a few Albanian companies in the North Macedonian market, but there is very little interest from North Macedonian companies to enter the Albanian market. Also the governments of the two countries should consider the possibility of removing any tariff between them, in order to make CEFTA really a free trade agreement, which in many cases hasn’t been until now. The two countries in general suffer from a lack of infrastructure connections. The ‘’Rruga e Arbrit’’ that is being constructed will somehow ameliorate this problem, but it is not sufficient. In the future should be considered a rail connection. Some of these problems have been considered in the mini-Schengen initiative, but it needs to be seen how it will work in practice.

On the political area, the main point

is Albania’s temptation to interfere in the internal affairs of North Macedonia

by supporting and helping the Albanians there to better present their demands. The

position of the Albanian population in North Macedonia has improved with the

Zaev government, but still short of a full integration in the state

institutions and the political and economic life of the country. A new

VMRO-DPMNE government that will include also an Albanian political party,

hardly will go backwards in this direction. In this view, the role of the

support and interference of the Albanian government in the future has to be

diminished. This will allow the Albanians in North Macedonia to became a factor

by itself inside the country and not to be seen by the majority of Macedonians

as an extension of Albania and consequently as a ‘’Trojan horse’’ inside the

country.

[1] Kristaq Prifti, Popullsia e Kosovës 1831-1912, Akademia e Shkencave të Shqipërisë, 2014

[2] Muhamet Shatri, Kryengritja e Përgjithshme shqiptare kundërosmane e vitit 1912, Libri Shkollor 2016

[3] Ivo Banac, The National question in Yugoslavia, Cornell University Press, 1988

[4] Edvin Pezo, Komparativna analiza jugoslovensko-tursko konvencije iz 1938 i ‘’džentelmenskog sporazuma’’ iz 1953. Pregovori oko iseljavanja muslimana iz Jugoslavije u Tursku, pg. 118 Tokovi Istorije, 2\2013

[5] Vladan Jovanović, Iz SRFJ u Tursku, 23\06\2013 https://pescanik.net/iz-fnrj-u-tursku/

[6] Rethinking Albania’s Foreign and Regional Policy, Policy Paper (Tirana: Albanian Institute for International Studies, AIIS, 2018)

[7] Macedonian President Warns of Albanian Threat to Sovereignty, Voice of America, March 07, 2017 https://www.voanews.com/a/macedonian-president-warns-of-albanian-threat-to-sovereignty/3754238.html

[8] Aleksandar Vasovic, Russia accuses NATO, EU and Albania of meddling in Macedonia, March 2, 2017, Reuters https://www.reuters.com/article/us-russia-macedonia/russia-accuses-nato-eu-and-albania-of-meddling-in-macedonia-idUSKBN169262

[9] Adri Nurellari, Paradoksi i demokracisë me shqiptarët e Malit të Zi dhe Maqedonisë: më shumë peshë me më pak vota, https://sbunker.net/teh/88688/paradoksi-i-demokracise-me-shqiptaret-e-malit-te-zi-dhe-maqedonise-me-shume-peshe-me-me-pak-vota/

[10] Maqedoni/ Gruevski sulmon shqiptarët dhe gjuhën shqipe, Koha Jonë, 12 shkurt, 2017 http://www.kohajone.com/2017/02/12/maqedoni-gruevski-sulmon-shqiptaret-dhe-gjuhen-shqipe/

[11] Ministria për Evropën dhe Punët e Jashtme, Takimi i parë ndërqeveritar Shqipëri-Maqedoni, https://punetejashtme.gov.al/takimi-i-pare-nderqeveritar-shqiperi-maqedoni/

[12] “Bilateral and Regional Trade Agreements Notified to the WTO”, WorldTradeLaw.net, http://www.worldtradelaw. net/databases/ftas.php

[13] Krisafi, L. ‘The case of Albania’, in Medak. V (ed). Effects of stabilization and association agreements and CEFTA2006 on WB6 European Integration and Regional Cooperation: Achievements and ways forward. European Movement in Serbia, 2018

[14] Ibid.

[15] Integrated Presevo-Tabanovce border crossing starts operating, Belgrade/Presevo, 26 August 2019, https://www.srbija.gov.rs/vest/en/144300/integrated-presevo-tabanovce-border-crossing-starts-operating.php

[16] Maqedonia bllokon produktet shqiptare, 25 nëntor 2015, Koha Ditore https://archive.koha.net/?id=27&l=85883

[17] Maqedonia bllokon produktet shqiptare, Panariti: Reciprocitet, Monitor, 19\12\2016 https://www.monitor.al/maqedonia-bllokon-produktet-shqiptare-panariti-reciprocitet/

[18] Krisafi, L. ‘The case of Albania’, in Medak. V (ed). Effects of stabilization and association agreements and CEFTA2006 on WB6 European Integration and Regional Cooperation: Achievements and ways forward. European Movement in Serbia, 2018

[19] Rethinking Albania’s Foreign and Regional Policy, Policy Paper (Tirana: Albanian Institute for International Studies, AIIS, 2018)

[20] Ibid.

[21] North Macedonia FM prepared to go solo for EU accession bid, Euronews, 12/12/2019 https://www.euronews.com/2019/12/10/north-macedonia-fm-prepared-to-go-solo-for-eu-accession-bid

[22] Maqedoni: Lëvizje e lirë për Shqipërinë, Radio Evropa e Lirë, 12 shurt 2012