JENS BASTIAN

Introduction

China’s flagship foreign policy project is the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).[1] Since its official launch in 2013 by President Xi Jinping the BRI invests on a global scale in land-based and maritime projects, primarily through transport connectivity and trade enhancing infrastructure. Under the aegis of the BRI promises of “shared prosperity” are being promoted by the political authorities in Beijing to participating countries. China’s BRI combines unprecedented amounts of investments and loan funding for ambitious infrastructure projects across continents, regions and individual countries. Beijing-based policy banks are the primary providers of funding arrangements for these projects.

For the European Commission in Brussels and individual EU member states the BRI raises profound questions concerning their political relationship with China. While the Commission seeks to develop a coherent strategy vis-à-vis China’s BRI ambitions, Beijing is busy offering loan facilities, Chinese labour and services for the construction of bridges, highways and the modernization of ports and railways across Europe. The ability of the EU to speak with one voice in negotiations with China is being challenged through institutional settings such as the 17+1 network of countries from Central, Eastern and Southeast Europe cooperating with Beijing.

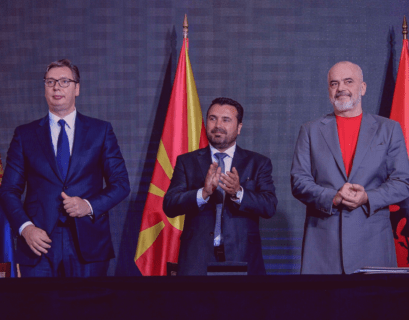

The utility of the BRI is an ambitious but at the same time contentious work in progress. It will extend only as far as it is able to generate tangible and sustainable outcomes benefiting not only China but also participating countries who engage in this endeavor. China’s reach into Southeast Europe is taking place because it sees current and future value in the region. Equally, governments and businesses from Athens over Tirana to Skopje, Belgrade and Sarajevo are all too eager to attract Beijing’s attention and benefit from its deep financial pockets.

At the second Belt and Road Forum (BRF) held in Beijing in April 2019, China’s President Xi Jinping stipulated that since the BRI was officially launched in 2013 China had signed more than 170 BRI-related agreements with more than 125 countries. The 2019 Forum was attended by heads of state and government from 37 countries, including Russian President Vladimir Putin, Italian Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte, President Aleksandar Vučić from Serbia as well as the prime ministers from Greece (then Alexis Tsipras) and Hungary, Viktor Orbán.[2]

China’s infrastructure diplomacy during the implementation of the BRI in the course of the past years is now being challenged and subject to recalibration in light of the Covid-19 pandemic. China’s outreach activities in international relations are now being supplemented by what the authorities in Beijing label the “Health Silk Road”. This was illustrated by China’s ‘mask diplomacy’ during March and April 2020 vis-à-vis countries participating in the 17+1 network. The donation of medical supplies, provision of personnel protective equipment (PPE) and availability of embedded Chinese health advisors constitute new characteristics and challenges of China’s engagement with countries in Central, Eastern and Southeast Europe.

I. China’s policy instruments in Southeast Europe

How do Chinese political authorities frame the BRI in Southeast Europe? When Chinese representatives visit the region they regularly emphasize how “to dovetail” the Belt and Road Initiative with the development strategies of participating countries in the region. The individual country cases in section II will provide examples of such “dovetailing”. Today, few political leaders in the region and representatives from the corporate sector name Moscow or Ankara as a model. Increasingly Beijing is becoming a magnet for decision makers in Southeast Europe.

When the Chinese Premier Li Keqiang visited Dubrovnik in April 2019 to attend the 9th China-Central and Eastern European Countries (CEEC) Business Forum, he underlined the momentum of economic and commercial cooperation within the so-called 17+1 network[3].

- In 2018, China’s trade with the Central and East European (CEE) countries increased by 21 percent, reaching a record high of 82.2 billion U.S. dollars;

- Growth of China’s imports from CEE countries outpaced that of exports by five percentage points;

- China’s investment in CEE countries increased by 67 percent in 2018;

- Investments are most prominent in the energy, mining and home appliance sectors;

- There were over 1.4 million tourist arrivals from China to CEE countries in 2018 while 350.000 visitors came from CEE countries to China;

- China is using a growing variety of financing institutions to secure the flow of credit for major infrastructure projects and acquisitions in Southeast Europe. State-owned policy banks (e.g. China Development Bank and Exim Bank of China), the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), the Silk Road Fund, and the China-CEEC Inter-Bank Association highlight the diversity of Chinese [backed] financing institutions that are active in the region.

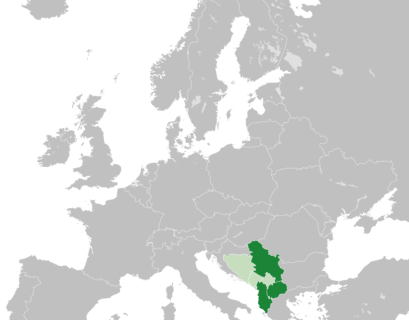

These various economic, commercial and financial sector developments highlight an emerging reality in Southeast Europe: China matters to the region. But make no mistake about country-specific differences. Some are more equal than others. Greece and Serbia stand out as the flag bearers of Chinese investments, while lending for infrastructure projects has targeted Albania, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina as well as North Macedonia. The outlier is Kosovo which is not on the map of Chinese activities in the region. China has steadfastly refused to recognize the sovereignty of Kosovo, thus siding with Serbia. The flip side of this argument also holds, namely that the region of Southeast Europe is of growing economic, commercial and strategic importance for China (Bastian 2018). Apart from the numerous infrastructure projects, the most visible sign of this importance is the effort China has put into establishing and subsequently enlarging an institutional architecture for bilateral cooperation under the heading “17+1 framework”.

Soft Power Capacity

With the view to promoting cultural diplomacy in more than 140 countries worldwide, China has established a network of Confucius Institutes (CIs) on university and college campuses. The mandate of these non-profit cultural centers is to highlight the Confucian heritage, promoting Chinese language(s) and present the diversity of its many cultures. There are currently 25 such CIs across Southeast Europe (see table 1 next page). The first was created in Serbia in 2006. Romania stands out with a total of four such CIs, followed by Hungary and Turkey with three each, respectively. Again, only Kosovo does not feature a Confucius Institute. All of these Confucius Institutes are located at universities across the region. The Institutes are administered by Hanban, a division of China’s education ministry. Hanban pays for the Institutes’ operational costs, selects textbooks and hires, trains and pays for Chinese language teachers in Southeast Europe.

The spreading presence of Confucius Institutes across Southeast Europe’s university landscape is also important for another reason. They should not only be viewed as a network of language institutes and staging cultural events. They can also serve as influence agencies to advance messages and developments important to China’s political authorities. The CIs frequently invite university academics from China to explain Beijing’s reasoning behind the BRI.

Table 1 China’s Soft Power Footprint in Southeast Europe – Confucius Institutes

| Country | Location | Year |

| Serbia | University of Belgrade, University of Novi Sad | May 2006 |

| Bulgaria | Sofia University St. Cyril + St. Methodius Veliko Turnovo University | June 2006 October 2012 |

| Hungary | Eotvos Lorand University University of Miskolc University of Szeged | September 2006 December 2011 Autumn 2012 |

| Slovakia | Slovak University of Technology | May 2007 |

| Turkey | Bogazici University Middle East Technical University Okan University | March 2008 November 2008 June 2012 |

| Greece | Athens University of Economics and Business University of Thessalia, Thessaloniki | June 2008 November 2019 |

| Slovenia | University of Ljubljana | August 2009 |

| Moldova | Free International University | September 2009 |

| Romania | Babeş-Bolyai University of Cluj-Napoca Transilvania University of Brasov Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu University of Bucharest | October 2009 March 2012 September 2013 November 2013 |

| Croatia | University of Zagreb | July 2011 |

| North Macedonia | SS Cyril and Methodius University | April 2013 |

| Albania | University of Tirana | June 2013 |

| Montenegro | University of Montenegro | September 2014 |

| Cyprus | University of Cyprus | September 2014 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | University of Sarajevo University of Banja Luka | December 2014 November 2017 |

Source: Compilation by the author. The list is structured by chronological order, i.e. when the first Confucius Institute was established in the respective countries of Southeast Europe. The compilation is mostly based on “Confucius Institutes Around the World – 2019” (Digmandarin 2019).

The soft power capacity of China’s footprint in Central, Eastern and Southeast Europe extends beyond the Confucius Institutes. China is also funding research institutes and think tanks “with Chinese characteristics”, university chairs and scholarships for university studies of citizens from countries in Southeast Europe in China. In April 2017 the Chinese Academy for Social Sciences (CASS) established the China-CEE Institute, a think-tank based in Budapest, Hungary. It was China’s first think tank created in Europe. In September 2015 a second Chinese think tank was established in the Czech Republic. The New Silk Road Institute Prague seeks to strengthen ties between Asia and Europe. Like its peer in Budapest, the Prague Institute is registered as a nonprofit charitable organization. Finally, in November 2019, CASS signed a cooperation agreement with the Greek Foundation Akaterina Laskaridi for the establishment of a Chinese Studies Centre in Athens.

In October 2015 the Silk Road Think Tank Network (SiLKS) was launched to provide intellectual support to the Belt and Road Initiative. SiLKS defines itself as an informal international network that was initiated jointly by think tanks, international organizations, and relevant institutions from more than thirty countries. It focuses on BRI-related research, information and knowledge sharing as well as capacity development on policy research and consultation. Among the 55 international members and partners from 27 countries (as of March 2019) are also four participating think tanks from Southeast Europe, namely:

- The Center for International Relations and Sustainable Development (CIRSD) in Serbia;

- The Center for Strategic Research of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Turkey (SAM);

- The Geoeconomic Forum of Croatia;

- Századvég School of Politics Foundation in Budapest.

At the bilateral level, Sino-Southeast European scientific and academic cooperation is equally making inroads. The Montenegrin Academy of Sciences and Arts (MASA) and the Chinese Academy for Social Sciences (CASS) signed a cooperation agreement in September 2019. The agreement calls for the two academies to enhance bilateral partnership through the exchange of scholars, joint conferences and cooperative research projects in the fields of natural sciences and technology. MASA was also invited to apply for membership in the newly established Alliance of International Science Organizations (ANSO), which was initiated by CASS and 36 other Chinese research institutions in November 2017 to promote global scientific and technological cooperation.

In individual countries of the Western Balkans China is also establishing – with the assistance of local partners – so-called “Centers for Promotion and Development of the Initiative “One Belt and One Road”. These centers serve to highlight Chinese policy initiatives in the host country, areas of potential cooperation and give Beijing’s diplomats a platform to interact with civil society representatives[4]. In other countries, such soft power institutions take the form of “One Belt One Road” Trade and Investment Promotion Centres, as is the case in Belgrade in cooperation with the Serbia Chamber of Commerce and Industry.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina bilateral soft power institutions operate under the heading of the Bosnia-China Friendship Association and the BiH Belt and Road Construction and Promotion Center. These associations and/or centers organize seminars for the political, academic, business, and media sectors with the frequent participation of the Chinese ambassador in Sarajevo. They serve to exchange views on current and future BiH-China relations, highlight the development potential brought by the Belt and Road Initiative and emphasize that participating countries should not miss the opportunities provided by China[5].

The Covid-19 pandemic has shed a strong light on another form of Chinese soft power intervention. As the coronavirus spread from its origin in Wuhan, Hubei province to other parts of China, neighboring countries and continents, crisis management became paramount. Included in these efforts is Beijing’s ‘coronavirus diplomacy’ across Europe. The provision of medical supplies and protective gear to Italy, Albania, Serbia, Greece, Slovenia and Bosnia-Hercegovina is being deployed abroad. These deliveries are taking place in combination with China’s Red Cross who is sending health experts to host countries. In 2017, the Chinese Red Cross established the Silk Road Fraternity Fund which is now a major international agency providing and coordinating China’s coronavirus diplomacy and by extension the country’s crisis management image abroad.

II. Country cases

What characterizes China’s relations to individual countries in Southeast Europe? The following country case studies are introduced in order to highlight their relevance to Chinese policy in the region. We first focus on Albania, a country in which China is not a newcomer. We then turn our attention to the situation in Bosnia Herzegovina. Both examples serve to underscore what China is doing, for what reason these activities are taking place, and what means Beijing is applying to implement its strategic objectives, e.g. in terms of equity investments or lending for infrastructure projects. The country cases also include brief updates relating to developments confronting the Covid-19 corona virus crisis and how these impact bilateral relations with China.

Albania: The Return of China

China’s growing footprint in Southeast Europe appears as a novel initiative in various countries of the region. But it also comes with some historical baggage and economic legacies. Albania represents a country in the Western Balkans where it is more accurate to speak of a return of China. The history of Sino-Albanian economic cooperation during the period 1949-1978 cannot be separated from what Beijing is undertaking in Tirana today. Both countries established diplomatic relations in November 1949. In fact, Albania was the first country to recognize the People’s Republic of China. Both states joined as brothers in (ideological) arms to denounce ‘Soviet revisionism’ after the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in 1956[6]. A further cornerstone of their ideological cooperation consisted in the condemnation of Tito’s Yugoslavia undertaking a “separate road to socialism”.[7]

China’s support for the Albanian economy was crucial during the 1970s. In 1973 and 1974, Albania sent 24 percent of its exports to China, from where it received 60 percent of its total imports (in investment goods and financed through Chinese financial support). The years 1971-1975 can be considered “the golden years of bilateral economic cooperation”[8]. There were 132 capital investment initiatives in all economic sectors. Major investments such as Fierza HPP, the Metalurgical Combine in Elbasan, the Ballsh Refinery were financed with loans from Chinese banks, while the technology and the knowhow was brought in from China. When Albanian workers met with Chinese technicians to discuss a project, the manner in which they were able to overcome the linguistic hurdles of Chinese and Albanian was by speaking together in Russian!

While economic reliance on China grew, Sino-Albanian political relationsgradually deteriorated from the mid-1970s onwards. Albania’s leadership under Enver Hoxha disagreed with certain aspects of Chinese foreign policy making, in particularly the path breaking visit of the U.S. President Richard Nixon to China in February 1972. Hoxha also distanced himself from the Chinese “Three Worlds Theory”.[9] The breakup finally arrived in 1978 when China under Deng Xiaoping terminated its special trade relations and diplomatic tête-à-tête with Albania.

After a hiatus of more than 30 years, China’s return to Albania was primarily motivated by investments in the transport and energy sectors, respectively.

- In February 2014, Jiangxi Copper, China’s biggest copper producer, acquired a 50 percent equity shareholding of Nesko, a Turkish company operating copper mines in Albania for USD 62.4 million. Nesko is part of Turkey’s Ekin Maden mining and metals group which operated through an Albanian subsidiary, Beralb, the Munella and Lakrosh copper mines as well as the Fushe Arrez flotation plant in Albania.

- In March 2016, Canada’s Banker’s Petroleum sold its exploration and drilling rights in the Albanian oil fields of Patos-Marinze and Kucova to affiliates of China’s Geo-Jade Petroleum for a price of 384.6 million euros.

These initial Chinese investments in the Albanian energy sector can be seen as anchor investments. They served as a catalyst for follow-up activities by Chinese companies in other sectors.

- In October 2016, China Everbright andFriedmann Pacific Asset Management Ltd.(both based in Hong Kong) acquired 100 percent of the shares in Tirana International Airport (TIA). The acquisition included a concession license to operate the airport until 2027.

These recent equity investments highlight the changing nature of Sino-Albanian economic cooperation. Today, Albania exports energy materials to China, whereas in the 1970s the profile of bilateral trade was precisely the other way around. Equally, 40 years ago the Chinese state was a credit provider to the Albanian state. Today, Chinese companies, some of which operate out of Hong Kong, are equity investors in Albania, acquiring shareholdings from private foreign companies. Finally, the role reversal of Sino-Albanian cooperation is also apparent in the following observation: In the 1960s and 1970s, China sought to support an entire economy in Albania. Today, Chinese companies focus on selected sectors such as energy and transport infrastructure in order to cater to domestic resource requirements (e.g. copper and petroleum) or they identify transport infrastructure projects with considerable growth potential, such as the Tirana International Airport.

The growing Sino-Albanian ties also extend to cooperation during the Covid-19 pandemic. On April 25th, 2020 the Albanian Deputy Minister of Health and Social Protection Mira Rakacolli and Deputy Minister for Europe and Foreign Affairs Etjen Xhafaj both welcomed a consignment of medical supplies donated by the Chinese government at Albania’s Tirana International Airport. China’s assistance to help the country fight the coronavirus pandemic included testing kits, protective garments, face masks, goggles and gloves for hospital workers. Words of gratitude and expressions of solidarity were exchanged with the Chinese ambassador to Albania, Zhou Ding.[10]

Bosnia-Herzegovina: China steps-in to build hydropower plants

After numerous delays, a major China-financed infrastructure project in Bosnia and Hercegovina appears to be ready for launch. In September 2019, the construction of public utility Elektroprivreda BiH (EPBiH) 450 MW Unit 7 at the Tuzla thermal power plant received the green light from the Council of Ministers in Sarajevo. A Bosnian consortium of civil engineering companies is carrying out the preparatory work. Once completed, the next phase of the construction project is handed over to China’s Gezhouba Group Company and Gunagdong Electric Power Design Institute.

The increased volume of electricity that Unit 7 in Tuzla is expected to produce will be coal-based. The long-planned investment is 85 percent financed by a loan from China’s Export-Import Bank, totaling 614 million euro. The government of Bosnia’s Federation entity is providing a loan guarantee for the project’s costs to Exim Bank. The total cost of the project is reported to reach 722 million euro, making it the single largest foreign-financed infrastructure initiative in the country. The details of this Sino-Bosnian project are significant for a number of reasons.

- [11] This membership includes adherence to rules and standards in public procurement procedures and environmental impact assessment. Sarajevo has also committed to follow EU rules on state subsidies in the energy sector. On the basis of these obligations the loan guarantee which Bosnia’s Federation entity is providing to China’s Exim Bank can constitute an infringement of state aid regulations. Put otherwise, the question asked in the corridors of Brussels and Sarajevo is the following: Is Bosnia allowed to provide such a guarantee for a controversial power plant project under current EEC regulations?

These controversies about Chinese lending, the construction of coal fired power plants and loan guarantees provided by federation authorities in Bosnia Hercegovina frequently overshadow another aspect of the debate. To what degree is the public involved in the consultation and even the decision-making process? There are examples elsewhere, but not yet in the Western Balkans, where China is being told it cannot continue with certain energy projects if it doesn’t comply with environmental impact assessment requirements and an adequate consultation process with civil society. To illustrate: in June 2019, the National Environment Tribunal in Kenya revoked the environmental licence of the Chinese company Power Global, thus blocking further construction of the country’s first coal-fired power station.[12] Is it a matter of time, until the Kenyan example reaches Bosnia and Herzegovina or any other Western Balkan country?

The Covid-19 pandemic is closing borders and limiting commercial interaction between countries, but that does not stop deal making with Chinese characteristics in Bosnia-Hercegovina. In April 2020, the shareholders of Bosnia’s aluminum smelter Aluminij d.d. Mostar approved a revised offer by Israel’s M.T. Abraham Group and its Chinese partners – China Machinery Engineering Corporation (CMEC) and China Nonferrous Metal Industry’s Foreign Engineering & Construction (NFC). The Sino-Israeli consortium agreed an initial 15-year lease agreement of the production assets of the ailing aluminum producer. The government of Bosnia’s Federation is Aluminij’s single largest shareholder with a 44 percent stake. The government of Croatia controls 12 percent. The remainder is owned by smaller shareholders. The lease agreement commits the Sino-Israeli consortium to rehire all 900 workers over a period of five years. Apart from the foundry, Aluminij’s also has anode and electrolysis plants. Aluminij shut down operations in July 2019 over debt (approximately 220 million euro) incurred because of high electricity and aluminum prices.

Furthermore, China is actively engaged in assisting Bosnia-Hercegovina in crisis management against the Covid-19 pandemic. Since March 2020, China has repeatedly donated medical supplies. In addition, it has opened a channel for the authorities in Sarajevo to commercially procure assets in China (Bosnia Daily 2020). In a correspondence to his counterpart in Bosnia-Hercegovina, Presidency Chairman Šefik Džaferovic, president Xi Jinping recalled that 2020 is the 25th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic relations between China and Bosnia-Hercegovina.

III. The EU’s reaction to China’s growing footprint in SEE

For roughly two decades, countries in the Western Balkans have sought European Union membership. During this quest for integration, the region’s six countries have also interacted with other non-EU external constituents. Most prominently among these have been Russia[13] and Turkey. But since 2013 a new rival for Brussels, Moscow, and Ankara has appeared on the region’s political economy map. In fact, the label “rival” has to be qualified. Moscow, Brussels and Ankara have good reasons to see Beijing as a [potential] rival in the Western Balkans[14]. But Podgorica, Sarajevo, Skopje, Belgrade and Tirana have no such classification in stock for Chinese investments, loans and infrastructure projects that are being carried out across the region.

But since 2019 China is starting to face a much more pro-active European Commission. This assertiveness is not only confined to the enforcement of transparent financing arrangements, adherence to EU procurement standards and open tender procedures. The Commission in Brussels is also recalibrating its strategic outlook vis-à-vis China. In its March 2019 communication, the Commission labelled China

“simultaneously, in different policy areas, a cooperation partner with whom the EU has closely aligned objectives, a negotiating partner with whom the EU needs to find a balance of interests, an economic competitor in the pursuit of technological leadership, and a systemic rival promoting alternative models of governance”[15]

For those familiar with the diplomatic wording and rhetorical compromises necessary in Commission communications, the March 2019 EU-China strategic outlook represented a robust and, in many respects, new departure of describing the current relationship between the EU and China. But the statement should also not be over-interpreted. China can in fact read any kind of characterization of itself from the Commission’s communication. It may choose to emphasize the partner classifications, while downplaying the systemic rival label.

With the inauguration of the 16+1 network in April 2012 in Warsaw, Poland China joined the institution-building competition in Europe. Seven years later the network expanded to 17+1 after Greece joined at the Dubrovnik summit in April 2019. The 17+1 network is termed by Beijing as a “win-win” combination for participating countries from Central, Eastern and Southeast Europe. It is integrated in the Cooperation between China and Central and Eastern European Countries platform.Over the course of the past seven years, China solidified this institutional architecture which organizes the annual Central and Eastern Europe – China Summit. The headquarters of the 17+1 network are located in Beijing. The monthly working group meetings take place at the level of participating ambassadors in the Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Concerning the 17+1 platform the Commission explicitly argues that

“Neither the EU nor any of its Member States can effectively achieve their aims with China without full unity. In cooperating with China, all Member States, individually and withinsub-regional cooperation frameworks, such as the 16+1 format, have a responsibility to ensure consistency with EU law, rules and policies” (ibid, emphasis in the original).

It is precisely this need for consistency and unity of purpose vis-à-vis China that represents the biggest challenge for the EU, its member states and the accession countries in the Western Balkans. One central policy field concerns investment screening regulations. To back up its rhetoric and strategic recalibration vis-à-vis China, the Commission in Brussels adopted new regulations that established such a framework for screening non-EU foreign direct investment. The regulation entered into force in April 2019 and will fully apply across member states eighteen months later, i.e. from November 2020 onwards. The 27 EU member states, including the 12 EU countries that are part of the 17+1 platform, will have to adapt their national legislation to reflect the Commission’s investment screening regulations. While the EU regulation provides a framework, the right of each EU member state to decide whether or not to screen a particular non-EU foreign direct investment cannot be curtailed by the Commission in Brussels[16].

For countries in the Western Balkans the debate over the need for investment screening procedures, in particular with regard to China, is practically non-existent. In the case of EU candidate and accession countries, neither Serbia, Albania, Montenegro, Northern Macedonia, Kosovo nor Bosnia and Herzegovina have adopted such regulatory screening procedures. It will be telling to observe how the Commission in Brussels can insist on such screening mechanisms in the accession negotiations with Serbia and Montenegro and subsequently with Albania and North Macedonia.

Against this background the question remains: what is the EU doing in the Western Balkans regarding the consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic? Despite an initial ban on exports of medical gear to non-EU countries, supplies are arriving in countries of the region. But it appears, and not for the first time, that the EU is again losing the PR campaign vis-à-vis Beijing. Perceptions matter in this pandemic, even if facts on the ground contradict them. In reaction to the corona virus outbreak, the European Commission (2020) pledged an emergency assistance package to countries in the Western Balkans totaling more than 410 million euros[17]. But these considerable financial resources are being overshadowed by the donations and cargo planes that land in Tirana, Sarajevo, or Belgrade from Beijing.

Conclusions and outlook

Over the course of the past decade China has gained a strategic foothold in Southeast Europe. This was achieved through a growing network of infrastructure projects, lending by Chinese banks and rising trade volumes. In doing so, China is presenting itself as a partner with a long-term vision and deep financial pockets. Historical legacies and previous economic ties – e.g. with Albania and Serbia – have provided bridges for China’s return or introduction into the Western Balkans. Today, the country of choice for China is not Albania. Prime position in terms of volume of invested capital is held by Serbia. For Southeast Europe more generally, it is Turkey.

China’s activities in Southeast Europe are not exclusively BRI driven. Some of its investments, lending and infrastructure development activities took place before the official launch of the BRI in 2013. Even if some countries stand out – particularly investments in Turkey, Greece and Serbia – China’s approach comprises a regional perspective[18]. The only exception, for political reasons, is Beijing’s non-involvement in Kosovo, and hence adherence to Serbia. Furthermore, China is also learning from its engagement with countries in Southeast Europe. During the past decade, Beijing has formed a better understanding of the operational environment and political challenges it faces in the region, particularly in the Western Balkans. This body of experience translates into policy adjustments on the ground.

- Project finance is being diversified to include multi-lateral European institutions such as the EBRD or the European Investment Bank (EIB). In the case of the Pelješac bridge project in Croatia, Chinese construction companies are benefiting from co-financing arrangements provided by structural funding programmes of the European Union. This outreach to European funding institutions and programmes is also a reflection of Chinese policy banks becoming more restrictive in their own lending policies.

- The Peljesac bridge also raises a wider issue of the EU applying competition policy vis-à-vis China. The project is 85 percent financed through EU structural funds over which the Croatian authorities have discretion. But awarding the tender to the lowest bidder begs the question if subsidized state-owned enterprises (SOEs) such as the China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC) should qualify in the first place?, The Government Procurement Agreement (GPA)[19] of the World Trade Organization (WTO) stipulate under what conditions firms can join public tenders.

- There is a greater awareness among Chinese authorities that large-scale infrastructure projects in the region need to support the local economy, thus presenting additionality to SMEs and domestic sub-contractors. The initial approach of Chinese companies to provide the financing, the manpower and construction materials for such projects is increasingly challenged by civil society representatives, media outlets and is being acknowledged as obsolete by ministries in host countries.

- The tripartite Sino-Hungarian-Serbian railway project has been a lesson learned for Chinese authorities in the complexities of European Union Realpolitik. This experience includes demands for increased transparency in BRI-related infrastructure projects, an open procurement process according to EU rules in member states.

- As Chinese financed and constructed infrastructure projects materialize across the Western Balkans, the debate over its environmental impact has grown in volume. Particularly in Bosnia and Herzegovina the construction and modernization of coal-fired thermal power plants has put China on the spot. The contradiction of policy making is evident. President Xi Jinping has strongly advocated support for the Paris Climate Accord from 2016. But simultaneously Chinese banks are financing and Chinese firms constructing coal-fired power plants in Tuzla and have completed work on another thermal power plant in Stanari, Republika Srpska.[20]

Seen from the perspective of countries in the region we can argue that initially their interactions with China lacked policy coherence. The formulation of a comprehensive country strategy vis-à-vis China is gradually taking place.[21] Its definition is also the result of lessons learned in the course of the past decade when engaging with China. What we can observe is the transformation of ad hoc initiatives with China towards the emergence of a set of strategic priorities, a better understanding of the legal implications of infrastructure project finance with Chinese interlocutors, the preparation of independent feasibility studies and the acknowledgement of the urgency of capacity building in administrative expertise. This is a work in progress for most countries dealing with Chinese counterparties, particularly those in the Western Balkans. In short, countries in the region are in the process of developing agency and competence vis-à-vis China.

China’s engagement in the region is diversifying into sectors that were considered unlikely only six years ago. The original emphasis was on concessionary lending for infrastructure development and anchor investments that served as catalysts. Today, China’s bilateral cooperation projects include an expanding role in security arrangements. In the summer of 2019 Chinese officers were engaged in joint police patrols with their counterparts in selected cities in Croatia and Serbia. China’s telecommunications company Huawei is the provider of facial recognition cameras and software for three ‘Smart City’ projects in Serbia and Bosnia Herzegovina[22].

What makes China’s activities in Southeast Europe such a challenge for European policy makers is the observation that through the BRI countries in the region are putting themselves in a position to implement large-scale infrastructure projects without the need for EU [financial] assistance. Initially, the EU did too little to publicly challenge China’s deepening engagement in Southeast Europe. With the official launch of the BRI in 2013, China signaled its intention to expand investments and trade. As more countries from Southeast Europe signed up to the BRI, their political leadership saw an unprecedented opening: the need for infrastructure upgrades could be achieved through a policy with Chinese characteristics.

Government representatives from Tirana over Sarajevo to Belgrade and Podgorica continue to emphasize that their first-choice preference for doing business remains with the EU. But what happens when this rhetoric starts losing evidence on the ground? Is China prepared to present itself as a first-choice alternative for policy makers in the Western Balkans? Can they manage the inherent political and operational risks? EU officials are right to be concerned about the challenges these questions raise. China’s willingness to build roads, railroads and ports in the Western Balkans is proving difficult to resist. In the years to come the debate over these challenges will be daunting. Simultaneously, China will continue to fascinate and attract policy makers in the region. China is not looking at short-term, immediate results. The government in Beijing is focused on where China is going to be in the next 20 to 30 years. In Southeast Europe, the EU is facing a non-EU-external actor that is positioning itself to become an ally of choice for countries in the region.

Epilog: Covid-19 and Sino-Southeast European cooperation

As countries in Southeast Europe seek to cope with the consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic in their health sectors, across society and the emerging economic fallout they are also having to reconsider their bilateral relations with China. The same holds for China which is seeking to re-write the narrative of the corona virus. Beijing’s focus rests on switching from the incubator of a pandemic in Wuhan, Hubei Province to a pro-active global leader helping other countries in times of urgent need. Chinese assistance in delivering medical supplies for Albania, Greece, Serbia, Bosnia-Hercegovina and Turkey during the pandemic in March and April 2020 underscores its efforts at repositioning itself diplomatically and with practical on the ground support.

These outreach activities point to how China is using the pandemic as a further opportunity to highlight the advantages of its model of crisis management and international relations strengths. In addition, the Chinese cargo planes landing in southeast European capital cities loaded with face masks, pharmaceutical supplies and protective gear illustrate the capacity of China to intervene in other countries’ medical supply chains. Despite its well-intentioned actions China’s ‘donation diplomacy’ widens its perimeter of engagement. Such diplomacy can exhibit to an international audience what leverage China can muster in health supplies and pharmaceutical manufacturing.

The institutional capacity building energies it has undertaken in the course of the past decade in the region help in these endeavors. China has used the 17+1 network to organize video conferencing meetings on Covid-19 with participating countries from Central, Eastern and Southeast Europe. But the signature event for China and its relations to countries in Central, Eastern and Southeast Europe in 2020 has had to be postponed. The ninth annual summit of the 17+1 network was scheduled to take place in mid-April 2020 in Beijing. President Xi Jinping was to deliver the keynote speech and meet the participating heads of state from across the three regions. The fact that president Xi himself was to host the April event underscored the political significance Beijing is giving to the 17+1 network in Europe.

One key area of cooperation with China which countries in Southeast Europe will have to address concerns the disruption of complex and integrated global supply networks. This development has immediate consequences for the commercial shipping sector between China and its European maritime hub in the Port of Piraeus near Athens. Not only is container traffic expected to decline year-on-year. Moreover, the subsequent transport of these products and services through Southeast Europe and onward to Western Europe is currently constrained.

Another sector that will impact on countries in Southeast Europe concerns tourist arrivals and overnight stays from China. Over the course of the past decade countries such as Greece, Croatia, Montenegro and Serbia have increasingly focused their tourism policies on the accommodation of Chinese citizens visiting their cities, historic sites and coast lines. Given existing travel restrictions and freedom of movement limitations receipts from tourism arrivals will adversely impact domestic airlines, airports, cruise ships, restaurants, hotels, museums, etc.

Now with the corona virus we can observe how China is instrumentalizing the pandemic as leverage to enhance its strategic objectives. China is in an advantageous position – with regard to the delivery of practical assistance on the ground – to quickly organize and finance cargo planes full of medical supplies to Tirana, Belgrade or Sarajevo. Moreover, China’s soft power capacity with Confucius Institutes and the availability of the 17+1 network enable Beijing to complement medical assistance with a diplomatic offensive and repeated PR displays of its supposedly benign intentions.

During the crisis management of the Covid-19 pandemic a new element of international relations is being adopted by Chinese officials. We can observe numerous examples of the controversial “politics of generosity”[23] across Southeast Europe. Chinese diplomatic representatives emphasize that these endeavours of humanitarian and medical assistance are undertaken in the spirit of “jointly” building “a community with a shared future”[24]The provision of “mask diplomacy” (referring to face masks and protective gear provided by China) and the execution of such “politics of generosity” go hand-in-hand with the objective to win hearts and minds across societies in the region. Put otherwise, fighting the Covid-19 pandemic is yet another example of a non-EU external actor further expanding its political and economic footprint in Southeast Europe. This footprint now includes the health sector of countries that have scarce resources in an under-funded and under-invested public sector.

Finally, in the course of the past decade China has expanded its maritime reach and cross-border connectivity through its BRI. China’s signature foreign policy project critically relies on open borders, mobility of labour, as well as the export of goods and services. The inter-connectedness of global supply chains is another cornerstone for the advancement of the BRI. All these characteristics – mobility, connectivity and operational supply chains through new transport infrastructure – are now subject to restrictions by national governments across continents. In consequence, the BRI is facing unprecedented political and institutional hurdles in many participating host countries. We can therefore expect that the recalibration of the BRI, which was already under way before the Covid-19 pandemic – namely shifting priorities away from a focus on transport infrastructure and controversial energy projects financed by Chinese policy banks – will accelerate. Some observers therefore argue that the medical and pharmaceutical assistance China is now providing abroad is the precursor to the BRI being enlarged towards a “Health Silk Road”[25].

JENS BASTIAN is an independent economic consultant and financial sector analyst.

Bibliography:

Bastian, Jens. “The potential for growth through Chinese infrastructure investments in Central and South-Eastern Europe along the “Balkan Silk Road”, independent report commissioned by the EBRD, September 2017, [Online available]: https://www.ebrd.com/news/2017/what-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative-means-for-the-western-balkans.html, accessed 09. October 2019.

Bastian, Jens. “China’s Expanding Presence in Southeast Europe. Taking Stock in 2018”. Reconnecting Asia, December 19, 2018. [ONLINE] Available at: https://reconasia.csis.org/analysis/entries/chinas-expanding-presence-southeast-europe/.

Bastian, Jens. “The Embrace Between a Russian Bear and the Panda Bear. An Emerging Sino-Russian Axis”, ELIAMEP Working Paper No. 108/2019, June 2019.

Borrell, Josep. “The Coronavirus pandemic and the new world it is creating”, 24th March 2020, online available: https://eeas.europa.eu/delegations/china_en/76401/EU%20HRVP%20Josep%20Borrell:%20The%20Coronavirus%20pandemic%20and%20the%20new%20world%20it%20is%20creating (accessed 06.07.2020).

Bosnia Daily. “China Will Help BiH”, 10th April 2020.

CEE Bankwatch Network. “Stanari lignite power plant, Bosnia and Herzegovina”, [Online available]: https://bankwatch.org/project/stanari-lignite-power-plant-bosnia-and-herzegovina, accessed 11. October 2019.

China.org.cn. Full text of Chinese Premier Li Keqiang’s speech at 9th China-CEEC Business Forum, 13. April 2019, [Online available]: http://www.china.org.cn/china/Off_the_Wire/2019-04/13/content_74677826.htm, accessed 08. October 2019.

Digmandarin. “Confucius Institutes Around the World – 2019”. [Online available]: https://www.digmandarin.com/confucius-institutes-around-the-world.html, accessed 08. October 2019.

Doehler, Austin. “From Opportunity to Threat. The Pernicious Effects of China’s Belt and Road Initiative on Western Balkan-EU Integration”, Center for European Policy Analysis, September 2019.

European Commission. Joint Communication [with the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy] to the European Parliament, the European Council and the Council, EU-China – A Strategic Outlook, 12. March 2019, JOIN (2019) 5 final.

European Commission. “EU mobilises immediate support for its Western Balkan partners to tackle coronavirus”, 30th March 2020, online available: https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/news_corner/news/eu-mobilises-immediate-support-its-western-balkan-partners-tackle-coronavirus_en (accessed 06.07.2020).

Hackaj, Ardian. “China and Western Balkans”, Policy Brief, Cooperation and Development Institute, Tirana, March 2018.

Kuo, Lily. “China sends doctors and masks overseas as domestic coronavirus infections drop”, 19th March 2020, online available: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/19/china-positions-itself-as-a-leader-in-tackling-the-coronavirus (accessed 06.07.2020).

Mayerbrown. “EU Agrees on FDI Screening Framework”, 18. December 2018. [Online available]: https://www.mayerbrown.com/en/perspectives-events/publications/2018/12/eu-agrees-on-fdi-screening-framework, accessed 02. April 2019.

Qiyue, Zhang. The Single Soul of Empathy Dwelling in our Bodies”, Kathimerini (English edition), 23rd March 2020.

Tonchev, Plamen. “A Glimpse into China’s Soft Power in the Western Balkans”, in: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Briefing Political Trends & Dynamics, Chinese Soft Power in Southeast Europe, Vol. 3, 2019, pp. 18-24.

Turcsanyi, Q. Richard. “Slovakia’s Overdue China Strategy”, The Diplomat, 03. November 2017, [Online available]: https://thediplomat.com/2017/11/slovakias-overdue-china-strategy/, accessed 17. October 2019.

Xinhua News Agency. “Seminar on BiH-China relations held in Sarajevo”, 13. October 2019, [Online available]: http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2019-10/13/c_138467225.htm, accessed 15. October 2019.

Zickel, Raymond and Walter R. Iwaskiw. Albania: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress.

Zivanovic, Maja. “China’s

Growing Role in Serbia’s Security Field”, Bosnia Daily, 22. August 2019,

pp. 12-13.

[1] A word about terminology needs to be clarified from the outset. Since its inception by President Xi Jinping in 2013, China’s representatives use the term One Belt – One Road (OBOR). The term Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) introduced in 2016 is a linguistic adjustment to the English language. For our analysis we shall use the BRI terminology.

[2] A total of seven EU Member States were represented at the Forum through their Prime Minister (Austria, Greece, Hungary and Italy) or President (the Czech Republic, Cyprus and Portugal). To date (July 2020), 22 European countries have signed cooperation agreements with China on the BRI.

[3] China.org.cn (2019): Full text of Chinese Premier Li Keqiang’s speech at 9th China-CEEC Business Forum, 13. April 2019.

[4] Plamen Tonchev. “A Glimpse into China’s Soft Power in the Western Balkans”, in: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, Briefing Political Trends & Dynamics, Chinese Soft Power in Southeast Europe, Vol. 3. 2019.

[5] Xinhua News Agency. “Seminar on BiH-China relations held in Sarajevo”, 13. October 2019

[6] Raymond Zickel and Walter R. Iwaskiw. Albania: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress. 1994.

[7] When Albania became a member of the United Nations in December 1955, one of its key activities was to articulate and support Chinese political interests. Since China only joined the UN in 1971, it could rely on its port-parole in Tirana.

[8] Ardian Hackaj. “China and Western Balkans”, Policy Brief, Cooperation and Development Institute. (Tirana. 2018.)

[9] The Three Worlds Theory was advocated by Mao Zedong. It argued that the international relations of China are characterized by three political economy worlds: the first world consisting of “superpowers”, i.e. the United States and the Soviet Union, the second world of “lesser powers” (which included China), and the third world of “exploited nations”. The Three Worlds Theory served to justify the deepening of Sino-U.S. diplomatic and commercial relations following President Nixon’s visit to China in 1972.

[10] However, China is not the only non-EU external actor assisting Albania during the Covid-19 pandemic. In mid-May, the Qatar Fund for Development also sent a plane load full of medical supplies to Albania to support the country’s efforts in containing the outbreak of the corona virus.

[11] All six countries in the Western Balkans have joined the EEC. The compact is governed by legally binding directives under the Energy Community Treaty (ECT). The aim of this treaty is to bring the energy policies and environmental standards of the Western Balkans in line with those of the EU as a whole.

[12] The USD two billion deal was signed with Power Global to finance a new coal fired power plant. The planned unit is adjacent to a world heritage site of UNESCO. The project is being funded with an export credit from the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC).

[13] Jens Bastian. “The potential for growth through Chinese infrastructure investments in Central and South-Eastern Europe along the “Balkan Silk Road”, independent report commissioned by the EBRD. September 2017.

[14] Austin Doehler. “From Opportunity to Threat. The Pernicious Effects of China’s Belt and Road Initiative on Western Balkan-EU Integration”, Center for European Policy Analysis. 2019.

[15] European Commission. Joint Communication [with the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy] to the European Parliament, the European Council and the Council, EU-China – A Strategic Outlook, 12. March 2019, JOIN (2019)

[16] Mayerbrown. “EU Agrees on FDI Screening Framework”. 2018.

[17] €38 million are being made available in immediate support for the Western Balkans to tackle the health emergency. An additional €374 million from the Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance are being re-directed to help the socio-economic recovery of the region.

[18] Jens Bastian. “The potential for growth through Chinese infrastructure investments in Central and South-Eastern Europe along the “Balkan Silk Road”, independent report commissioned by the EBRD. September 2017.

[19] The GPA is a plurilateral agreement within the framework of the WTO. It regulates international competition to mutually open government procurement markets among signatory countries. Croatia accepted the GPA rules in 2013 and China signed the revised GPA in 2014.

[20] The Stanari power plant was constructed by China’s Dongfang and financed by the China Development Bank. The plant officially started commercial operations in September 2016. By that time Stanari was already out of date in terms of environmental standards. Its environmental permit stipulates compliance with the older EU Large Combustion Plants (LCP) Directive, not with the newer Industrial Emissions Directive (CEE Bankwatch Network 2019).

[21] In 2017, Slovakia’s government was the first country in the 17+1 network to develop an extensive “Strategy for the Development of Economic Relations with China 2017-2020” (Turcsanyi 2017).

[22] Maja Zivanovic. “China’s Growing Role in Serbia’s Security Field,” Bosnia Daily. (2019)

[23] Josep Borrell. “The Coronavirus pandemic and the new world it is creating”, (2020)

[24] Zhang Qiyue. “The Single Soul of Empathy Dwelling in our Bodies,” Kathimerini (English edition). (2020)

[25] Lily Kuo. “China sends doctors and masks overseas as domestic coronavirus infections drop”, The Guardian, (2020)