Sylë Ukshini Ph.D[1]

Abstract

The recognition of Kosovo’s independence by Israel in September of 2020 is a very important geopolitical issue, as it has an impact on developments in the Middle East and the Western Balkans. Also, due to all parallels or artificial similarities between them, this recognition confirmed that Kosovo’s independence would set a legitimate precedent for Palestinians, at the same time leaving other cases within Spain, Slovakia, Romania and other non-recognizing countries unstable. What is unique in the case of Kosovo is the fact that this recognition is mediated and supported by the USA, whereas the EU and the Arab League were unsupportive due to the fact that Kosovo plans to open its embassy in Jerusalem. But, despite these attitudes, the leadership of Kosovo has shown determination to fulfill this commitment that is part of the agreement of September 4th signed in Washington by Kosovo and Serbia, under the mediation of the Administration of President Donald Trump.

However, one of the key questions that inevitably arises is why recognition by Israel was so important to Kosovo. Kosovo Albanians have always identified their fate, long suffering under foreign occupation and cyclical deportations, with the fate of the Jews. Moreover, they consider that the two countries owe the USA for their existence. Moreover, in the history of the two nations we find many similar points, historical parallels and, above all, an excellent cooperation since the period of Ottoman rule in the Balkans. And exactly five decades after the Jewish people survived the Holocaust and declared the independent state of Israel, the American-Jewish political and diplomatic elite came to the forefront, showing increased interest in the cause of Kosovo Albanians during the 1990s. And without such support, which led to NATO military intervention in 1999, Kosovo’s freedom and independence would be inconceivable.

In this context, what remains impressive is that the small Albanian people of Kosovo, long oppressed by the Ottoman and Serbian state, offered their assistance to the Jewish community during World War II, when they were facing total annihilation by the Nazi German regime. Recently, books and studies have been published in Kosovo, Macedonia and Albania that reflect the authentic stories of members of the Jewish community in which this forgotten contribution is documented and affirmed. The historical presence of a small Jewish community in Kosovo can serve as a major impetus for rapprochement and cooperation between the two peoples, who have never had any visible issues.

Key Words: Jewish community, Kosovo’s independence, Israel, USA, EU, Holocaust, Vilayet of Kosovo, Palestine, diplomatic relations, NATO, ethnic cleansing, humanitarian intervention.

Introduction

13 years after the declaration of independence, Kosovo has been recognized by more than half of the world’s countries, by 117 United Nations countries. But the recognition by Israel is of particular importance, due to the fact that it dispels all the taboos, claims and parallels used by non-recognizing countries that the case of Kosovo will set an unwanted precedent. In this context, this recognition has confirmed that the refusal of recognition by the five EU countries results in instability, both politically and legally. Mutual recognition between Kosovo and Israel is part of the agreement of September 4th, 2020 in Washington, which deals with the normalization of economic relations between Kosovo and Serbia. Kosovo has also committed to open its diplomatic mission in Jerusalem, whereas Serbia has committed to move its existing embassy in Israel from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem.

In order to better understand the history of relations between Kosovo Albanians and Jews, namely Israel, this paper presents a detailed picture of the presence of the historical Jewish community in the Balkan region, namely in the present territory of Kosovo. So, this paper deals with the history of relations between Kosovo Albanians and the historical Jewish community from the period of the Ottoman state until today. On this occasion, parallels have been drawn in time between the political and cultural aspirations of Jews and Kosovars on their path to creating their own identities and independent states. At the end of the 20th century, when the socialist system ended in Eastern and South-eastern Europe, there was a lack of a complete and comprehensive treatment of Albanian-Jewish relations. Among the Albanians, tradition comprised a largely oral history, both for their national events and for their contacts and relations with the Jewish community in the former Vilayet of Kosovo.[2] As a result, this story, as well as the alignment of Kosovo Albanians alongside Jews threatened by Nazi terror, were superficially recognized even in academic circles. Even the few studies that existed in the period of socialism did not lack certain ideological constructs and prejudices.

The story of the salvation of the Jews must be written continuously, because this is an affirmative chapter in the relations between the two peoples, that will serve generations of friendly ties. Undoubtedly, a special merit for the beginning of a more special treatment of the presence of the historical Jewish community in Kosovo and the region belongs to the well-known British historian Noel Malcom who, in his book on the history of Kosovo[3], draws attention to this community and gives us a genuine scientific picture far from myth. Jews in Kosovo and other Albanian areas are a very important community in the Albanian environment, a harmonious environment in terms of minorities. The thesis comes as a genuine scientific study, far from the myths surrounding the reasons for rescuing and protecting Jews from extermination throughout history, with particular emphasis during World War II. It is a confirmed fact that Kosovo served as a safe place and transit to Albania for citizens from different countries in the region and Europe with different citizenships, but belonging to the Jewish nationality, who found salvation and protection among the Albanians. This contribution has also been documented by Albanian authors Shaban Sinani,[4] Monika Stafa[5], and Jakoel Josef, a Jewish author from Tirana, who collectively illuminate the contribution of Albanians in the salvation and protection of the Jewish population throughout history. An admirable work in this direction is recently being done by the Institute of Spiritual and Cultural Heritage of the Albanians in Skopje, which has recently published studies (Skënder Asani and Albert Ramaj)[6], and memoirs of Jewish families (Mimi Kamhi Ergas-Faragi)[7] that survived the Holocaust during World War II. Faragi[8], and the motive behind her work, contributed to my conversation in October 2019 with the Israeli Ambassador to Tirana, Noah Gal Gendler, a diplomat with an extensive career and knowledge of the region. He had advised me that more should be spoken and written on this topic, in order to make known the contribution of a small country to the salvation and protection of the Jews from danger during the course of history, with special emphasis during World War II.[9] Therefore, in this paper, based on new recently published studies and documents, we have tried to provide a more original insight to the presence of the Jewish community in Kosovo, their relations with Kosovo Albanians in different historical periods. Here is evidenced the contribution of Jewish personalities to the culture and history of Albanians, with special emphasis on Kosovo, but which to date has been recognized in a peripheral way by Albanians themselves. Undoubtedly, a central spot has been dedicated to the assistance and contribution of Kosovo Albanians, who themselves had been persecuted by the Serbian governments in Belgrade, in rescuing the Jewish community from Nazi persecution during World War II.

The issue of relations between Kosovo Albanians and Jews gained a new dimension after the end of the Cold War, when the ranks of the American-Jewish political and intellectual elite – the likes of Tom Latosh, Eliot Engel, Elie Wisel, Medeline Albright and many others – became strong spokesmen for the more powerful involvement of the USA administration in Kosovo in 1989/1999, namely the voice of concern about the persecution of Kosovo Albanians by the Serbian regime of Milosevic. Eliot Wiesel[10], a Holocaust survivor, Nobel laureate and international human rights activist, called in 1999 to stop Milosevic and support NATO intervention in Kosovo. “This situation (in Kosovo) requires action,”[11] was his message to US President Bill Clinton.

The last part deals with the role of the Israeli state and humanitarian organizations in providing assistance to the Albanian civilian population deported during 1998-1999 by the Milosevic regime, which will be remembered for the most serious crimes since the end of World War II. In this line, one thing is certain: the airstrikes, which were supported by the most powerful voices of the Jewish political and intellectual elite, paved the way for Kosovo’s independence and influenced the progressive development of international law. Whereas the recognition of the independence of Kosovo by Israel marks a very important moment in consolidating Kosovo’s international position and its integration into international organizations. What happened on February 1st, 2021 in Prishtina and Tel Aviv, which was considered a unique, important diplomatic event to the US Department of State as well. In addition, the development of Kosovo-Israel relations is a development which signals the non-recognizing countries, i.e., the five EU countries, that it is time to deepen their cooperation with Kosovo and give up the non-recognition attitude. On the other hand, Brussels and the Arab League have not welcomed the formalization of relations between the two countries, especially the establishment of the Kosovo embassy in Jerusalem.[12] This is a turning point in Kosovo’s foreign policy, a delicate step at a time when Brussels is aiming to restore the Kosovo-Serbia dialogue and reach an agreement on the normalization of relations between the two Balkan countries.

The questions that inevitably arise when we talk about the recognition of Kosovo by Israel are the following: What will be the future objectives of the USA in relation to Kosovo? Why did the USA support this recognition? What will be the actions of the EU and the Arab League regarding Kosovo’s decision to open a Kosovo embassy in Jerusalem? What will be the impact of this recognition in relation to the five EU countries and the Vatican that have not yet recognized Kosovo?

Regardless of the forthcoming debate on this issue and diplomatic alternatives, this recognition breaks all taboos and imaginary paradigms regarding the reasons for non-recognition of Kosovo, and proves that independence of Kosovo is “sui generis.” And as Yonatan Touval says, as an analyst at the Israel Institute for Regional Foreign Policies, “For the 12 years since Kosovo declared its independence, history has shown that it has not had a negative impact on [Israel’s] conflict with the Palestinians.”[13]

Parallels in History and culture

Just a month before the declaration of the independence of Kosovo, in a public letter published in The Jerusalem Post on January 2nd, 2008, Political Science Professor Shlomo Avineri at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem wrote: “As Jews, who have been stateless for a long time, many of us understand and support their [Kosovar Albanians’] cause for self-determination and independence.”[14]

The comparative remark of Professor Avineri is a meaningful parallel which points out that the two countries, as relatively small nations, have always fought for their right to live in freedom. The similarity of their historical journeys to freedom has led to reciprocal understanding, which was precisely the reason why Albanians offered shelter, protection and hospitality to the Jewish community in response to the horrors of World War II. Half a century later, it was the Jews, their diaspora, and the state of Israel that came to the aid of Kosovo Albanians, who were the target of the 1998-1999 genocidal threat by the fascist regime of Milosevic.

It is no coincidence that Milosevic’s crimes in Kosovo, Croatia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina are in many ways comparable to those of Hitler and among the most serious crimes that have been carried out since World War II ended. According to Human Rights Watch and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), nobody could have predicted the speed and scale of deportations of the Albanian civilian population within three months, March-May 1999, by the Serbian forces. These figures indicate that by early June 1999, more than 80 percent of the entire population of Kosovo and 90 percent of Kosovar Albanians were displaced from their homes.[15]

The extermination attempts towards the two ethnic communities within a fifty-year span had tremendous impact on international law, marking fundamental positive changes. The atrocities the Jewish community experienced during World War II resulted in the independence of Israel, just one day after Britain’s withdrawal from the country in May 1948. The persecution and expulsion of Kosovo Albanians under the Yugoslav communist regime – precisely under the Serbian one – continued till the moment NATO intervened for humanitarian and regional security reasons, after the regime refused to agree on any compromise or political solution. The US and the EU were determined to show the Serbian regime in Belgrade that late 20th-century Europe reflected that of 1937, when the Munich Agreement was signed.

The intervention was undoubtedly the result of the democratic developments that took place after the end of the Cold War, when human rights were favored over state sovereignty. At the same time, the NATO intervention paved the way for the UN civilian and military administration in Kosovo. Under the mediation of UN Special Envoy, former Finnish President Martti Ahtisaari, exhaustive Albania-Serbia negotiations were held regarding the final status of Kosovo, and, in compliance with the recommendations of the Ahtisaari Plan, Kosovo declared its independence on February 17th, 2008.[16]

Most of the countries that recognized Kosovo’s independence, such as the US and those within the EU, justified their decisions arguing that Kosovo’s independence was a unique, unprecedented exception – sui generis – and it could not be compared to other cases elsewhere.[17] Those countries that do not recognize Kosovo’s statehood, including Russia – which has recently annexed Crimea – China, Iran, and Syria, justify their non-recognition by referring to international law. This is in spite of the fact that in 2010, the International Court of Justice concluded that Kosovo’s independence does not violate any international law.[18]

Belgrade’s opposition to Kosovo’s statehood is reminiscent of the denial of the state of Israel by some Middle Eastern countries, primarily Iran and Syria, as well as anti-Semitic groups such as Hezbollah. Their example has been actually embraced by Belgrade, which, apart from during the world war periods, has brutally ruled Kosovo since 1912. It is sabotaging and trying by all means to curb the internal and international consolidation of Kosovo’s statehood. Belgrade often makes use of offensive language and racist tones, such as the use of the detrimental term “shiftari“[19] instead of the international term “Albanian.” Furthermore, the current Serbian government makes use of the very same policies followed by the Milosevic regime; it manipulates certain political groups of local Serbs, which make up about 5 percent of Kosovo’s population. These are mainly controlled by the supporters of the current Serbian President Vucic and other criminal groups established during the Milosevic regime, within Serbian settlements in Kosovo.

Among other things, Belgrade’s hostile attitude towards Kosovo’s independence is identical both in form and content to the Serbian hegemonic attitude and mentality towards Albania, in the first half of the 20th century. In 1912 Serbian diplomacy claimed that the independence of Albania “is desired neither by us nor by Europe.” Similarly, in relation to the issue of Kosovo’s independence, it was not solely stipulated that it allegedly violated international law; it was also systematically promoted as a policy of division and violation of territorial integrity, speculations to which Kosovo was familiar following the establishment of the Yugoslav constitution of 1974.

Unlike Belgrade, the other non-recognizing countries – including the five of the EU – have never been considered by Kosovo as states with hostile intentions towards Kosovo. Rather, their stances have been interpreted as interest-determined approaches as well as attitudes for national and regional balance. However, after the July 2010 verdict of the International Court of Justice – the highest institution of justice of the UN – clearly stipulated that the declaration of Kosovo’s independence had violated neither international law nor UN norms, Kosovo has incessantly argued that there is no political or legal argument to delay its recognition. No parallels could be drawn between Kosovo and Catalonia[20] or Palestine, whereas the Crimea occupied by Russia is utterly a different issue. Above all, the statehood of Kosovo must be considered within the context of the dissolution of the multinational Yugoslav state, which resulted in the creation of six new states, as it was the case with the dissolutions of the Soviet Union, the Ottoman Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Nevertheless, the recognition of Kosovo by about 120 countries has openly demonstrated that the claims and so-called “arguments” of Serbia are unsustainable. The recent recognition of Kosovo by Israel on September 4, 2020[21], is also noteworthy. Without a doubt, it was undertaken thanks to the contribution of the most important ally of Kosovo, the United States of America. The timing and the mode of this recognition has special significance for Kosovo. It debunks Belgrade’s attempt to draw an artificial parallelism between the state of Kosovo and the Palestinian Authority, which, due to its “rock-hard brotherhood with Serbia” voted against Kosovo’s membership in INTERPOL.[22]

The Albanian Movement for Independence and Jewish Zionism

The efforts of the Albanians and those of the Jews for national emancipation developed roughly at the same period of time, both having belonged to the Ottoman Empire, precisely during the period of Sultan Abdyl Hamid II’s rule. In the last decades of the 19th century, while the Ottoman vilayets containing Albanian populations launched the Albanian Movement for Independence – known in historiography as the Albanian League of Prizren (1878) – under the leadership of Abdyl Frashëri, a great Jewish visionary, the famous Zionist Theodor Herzl (1860- 1904), was trying to persuade Istanbul to allow the nucleic foundation of a Jewish state in the Palestinean territory[23]. Just like the demands of the League of Prizren[24], Herzl’s requests were turned down by the sultan. It is argued that the Ottoman Empire, at the time dealing with armed movements of Armenians in Asia Minor and elsewhere, was not eager to support ideas that could lead to the creation of new states within its territory. It feared further disintegration.

Nonetheless, during this period, the European interest towards the Albanian cause and the “Holy Land” increased. This coincided with the introduction of the new Jewish colonies that settled in Palestine. In the first Zionist Congress, which was held in Basel in 1897, Herzl coined the idea to establish a Jewish state. Indeed, in his diary, later included in his book The Old New Land (1902)[25], he would write: “In Basel I founded the Jewish State.”[26] At the time, Sami Frashëri (1850-1904), one of the great ideologues of Albanian Renaissance, was drafting the first political treatise for the establishment of the independent state of Albanians, ” Albania – What It Was, What It Is and What Will Become of It.” It was published in 1899 in a printing house in Bucharest, far from Constantinople, where the imperial authorities had banned the publication of texts in Albanian.[27]

Obviously, the violent response of the Empire to suppress the Albanian Renaissance Movement, and its later concession in favor of the Balkan states in the Congress of Berlin, had a crucial impact on Sami Frashëri. On the other hand, the decisive turn for Herzl that marked his conversion to Zionism took place while he was working in Paris, as a correspondent for the prestigious Viennese newspaper Neue Freie Presse.[28] It was the time of the Dreyfus[29] case, a notorious anti-Semitic incident in France, which led to the set up trial of a Jewish captain of the French army on the false accusation of spying for the Germans.[30] “If you want [a Jewish state], this is no dream,” Herzl claimed as the father of Zionism. Indeed, half a century later this was a reality pioneered by enthusiastic Zionist David Ben-Gurion, first prime minister of the State of Israel.[31]

Hasan Prishtina and Alber Antebi

The Young Turk revolution of 1908 created the impression that the attitude of the new Ottoman government would favor the Albanian National Movement and the Zionist movement, considering the speculated influence of the Albanian and Jewish elements on the Young Turk party “Unity and Progress.” Taking this in consideration, prominent figures of the Albanian movement, such as Hasan Prishtina (1873 –1933), as well as their Zionist counterparts, such as Jewish community leader Albert Antebi (1873-1919)[32], welcomed the political change. However, these figures eventually realized the fact that the Ottomans opposed any separatist tendency, rejecting the Albanian and Jewish demands, the way they rejected the Armenian ones. In the meantime, Albanian and Jewish politicians started to defy the “Turkism” policy and ask for more autonomy for the Ottoman vilayets. The rise of this opposition signified hope for both Albanians, as well as the Jewish population in Palestine.

As one of the main ideologues of national Albanian emancipation, and the leader of the Albanian struggle against Serbian occupation, the prominent Kosovo Albanian politician Hasan Prishtina[33] commanded the Albanian rebellion and passed the demands of the Albanian population to the Ottoman government in Istanbul. At this time, in July 1912, well-known Albanian intellectual Mehdi Frashëri was appointed governor of Jerusalem. Although he governed there for only five months, he is remembered for his positive attitude towards the Jewish community in Ottoman Palestine. The attitude of the Ottoman official of Albanian origins was also reflected in the Jewish press in Palestine, Haor and Ha-Herut. On the other hand, the Arab press criticized his visit to the Jewish community in Richon Licion, and was especially unfavorable to Mehdi’s praise of the Jews. Impressed by the significant progress he witnessed in the Jewish settlements, in his speech, Mehdi had declared: “You are setting an example for the Arab villages. (…) You have become teachers for your Arab neighbors who do not know how to read and write, but look at what you are doing in this country.”[34] It should be noted that it was precisely this Albanian figure who in the League of Nations, in 1937, presented a proposal for the resolution of the conflict between Jews and Arabs in Palestine; his proposal was based on the Swiss model, and suggested the establishment of two cantons, one for Jews and one for Arabs.[35]

Although the outbreak of the Balkan Wars and World War I had a negative effect on Kosovo Albanians, who were subject of the Serbian occupation and persecution,[36] this period marked another turning point in the progress of the Zionist movement in Palestine. It culminated with the Balfourt Declaration of 1917,[37] which considered the establishment of a national homeland for the Jews in Palestine. The public promise of the British is considered as a crucial step towards the foundation of the state of Israel.

After surviving the unprecedented horror of the Holocaust, the Jews, under the leadership of Ben Gurion, achieved their goal and fulfilled the dream of Theodor Herzl. Conversely, Hasan Prishtina and the succeeding Albanian leaders had to carry on with their efforts against Serbian occupation for another half century. Coincidentally, several decades later, the fate of Kosovo Albanians was determined by policymakers of Jewish descent. Traumatized by the collective persecution of Jews, in March 1999 they became the most ardent proponents of the doctrine of humanitarian intervention in Kosovo, which in turn stopped the implementation of Serbian policy for the ethnic cleansing of Kosovo Albanians. Kosovo Albanians, like the Jews, had been expelled from their homes cyclically: during the period of the Eastern Crisis (1877-1878), between the two world wars, as well as during the violent dissolution of Yugoslavia in the context of the post-Cold War developments.

Undoubtedly, another beautiful parallel can be drawn in the cultural field, the inspiration that has existed in these two peoples for the revival and preservation of the language: Hebrew and Albanian. As noted by Josef Jakoel, a Jew of Albania and a connoisseur of the two peoples, the revival of Hebrew is a unique case in the history of philology, from a language that was “dormant” for centuries, it was quickly transformed into a living and cultivated language. Almost the same happened with the Albanian language, which was banned during the entire period of Ottoman occupation. Unwritten for centuries, it took off in the period of the National Renaissance[38] and in later periods became the most cohesive instrument of national unification.

Appreciative narrative on the Jews

The historical relationship and peaceful coexistence of Kosovo Albanians with the Jewish community is thought to date back to the period of ancient Dardania, when this territory was inhabited by the ancestors of the Albanians, the Illyrian-Dardanians. The presence of a Jewish community in Kosovo actually predates the Slavic invasion of the 7th century. However, the largest Jewish presence in this area is credited to the period of Ottoman rule. Many Jews who were expelled from Spain and Portugal during the 15th and 16th century sought refuge in the Ottoman Empire. The first specific mention of Jews in Kosovo comes in 1442, when two merchants in Prishtina, one Jewish, one Genoese, are described as holders of the tax-farm for silver production.[39]

The settlements of the Jewish in the Balkans – including Kosovo – were to be found almost exclusively in cities, and in the vicinity of synagogues. Their religious leaders were responsible for administrative matters of their community. It is also believed that members of Jewish community, like numerous Albanians, held important positions in the Ottoman state apparatus. The status and prosperity of the Jewish community in the Ottoman Empire, during the 15th and 16th century, is rooted in their contacts with Europe and the beneficial handling of these connections, not to mention the significant influence and wealth they brought along.

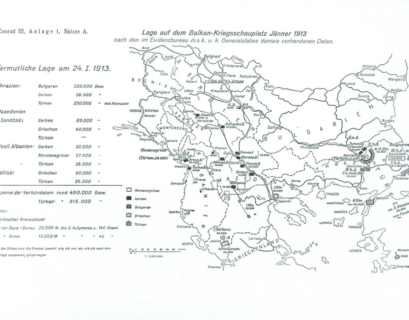

These elements also resulted in an increased presence of Jews in the territory of Kosovo – known then as the Vilayet of Kosovo – especially in its capital city of Skopje, with strong regional and international trade links. Skopje’s Jewish community grew rapidly, from thirty-two families in 1544 to a reported total of 3,000 people in the 1680s. The entire Jewish quarter was destroyed, however, when Piccolomini set fire to the city on October 26th, 1689.[40]The settling of the Jewish in Kosovo intensified particularly during the second half of the 19th century, and even the construction of the Skopje-fca railway is attributed to specialists of Jewish origin. According to the British historian Noel Malcolm, their presence in Kosovo during this period of time was noticeable in the big cities, such as Skopje, Pristina, Prizren and Gjakova.

According to the data from the Austrian archives, after the Salname of 1877 there were 50 Jews in the Sanjak of Pristina, that number growing to about 362 in 1903.[41] A significant number of the members of this community were merchants, pharmacists, mechanics, engineers, doctors, clerks and professors. For this reason, their impact on the lives of the Albanians and the other peoples within the Empire was substantial. In fact, many enterprises, businesses, as well as cultural and sports groups were owned by Jews. Additionally, it was the Jews who brought the technology of typography to the Empire, making possible the publication of books in various languages. Obviously, their presence also had a positive impact on the development of many professions within the Albanian space. This is encapsulated in an expression that is used by Albanians even today; a common way of portraying someone positively and praising their skills is to tell them “You are as smart as a Jew,” intended to show the appreciative attitude of Albanians for the Jewish community.

Albanians and Jews alike

The second decade of the 20th century was marked by major political changes in Southeast Europe. As the result of the Balkan Wars between 1912 and 1913 and World War I, two major empires – the Ottoman and the Austro-Hungarian – disintegrated. This led to the foundation of several new independent states and the territorial expansion of others. The Serbian occupation of Kosovo in October-November 1912 was accompanied by violence, deportation, looting and killing of members of the Albanian community. The followed pattern of brutality was the one implemented between 1877 and 1878 to Albanians of the Sanjak of Nis when they were expelled from the occupied territory of about 600 settlements, such as Pirot, Vranje, Leskovac, Prokuplje and Kursumlija. Even today, in Kosovo, they are called as “Muhaxhirs” (Trk.:muhacir), the Ottoman term which means emigrant, still widely used to refer to those who leave their homes and settle in another country.[42]

The Serbian government considered Albanians, Jews and other ethnic communities as enemies. They aimed to found a Greater Serbia, in which there would be no place for Albanians or other communities. Both Albanians and Jews were seen as a tangible obstacle to the Greater Serbia project and were, consequently, treated as accomplices to former Ottoman rule. From then on, the relations of the local population with the Belgrade governments were generally inimical. In relation to this issue, the German scholar Konrad Clewing[43] asserts that the conflict over Kosovo was, from the very beginning, a conflict for territory and political power between the Serbian/Yugoslav governments and the Albanian population in Kosovo. Yet, the Serbian expansionist projection was disguised with the forged myth that “Kosovo is the heart of Serbia.” Eerily reminiscent of other akin slogans, such as reference to the Port of Durrës and the north of Albania as “The lungs of Serbia”.

The significant contribution of Jewish scholars to Albanological studies

The Serbs, evidently perplexed by the fact that they reached the Balkans too late – they arrived only after the ethno-linguistic space of Albania was under Byzantine rule – had historically shown solid expansionist tendencies. These tendencies were rooted in myths and lies, which portrayed the Serbs as superior to Albanians. A parallel propaganistic approach was later used by the Nazi regime. In the face of the Serbian and Ottoman aggression alike, the sole arguments Albanians could rely upon were those related to their autochthony. Their position was reinforced by the work of several European scholars and Albanologists of Jewish origin. Norbert Jokl, Milan Shufflay, Joseph Roth, as well as Member of the Imperial Parliament and Austro-Hungarian publicist Leo Freundlich are among the most famous Jewish scholars who have contributed to Albanological studies.[44] Their independent studies confirmed that the Albanian language descended from the Illyrian language which, in turn, pointed out the autochthony of Albanians as the descendants of Illyrians. In present-day Kosovo, they are known as Dardanians, while their country was known as Dardania. Likewise, the Lama Dinner is an ancient Illyrian-Albanian feast, which is celebrated in the region even today.

Albanians are obliged to Leo Freundlich, who documented the persecution and misery Serbian soldiers inflicted on Albanians during the Balkan Wars of 1912-13. Along with Leo Trotsky, the famous Jewish Russian intellectual serving at the time as a war correspondent in the Balkans[45], Freundlich documented the Serbian atrocities against the Albanian population in two books, Albanien Golgatha: Anklageakten Gegen Die Vernichter Des Albanervolkes (Albania’s Golgotha: Indictments against the Destroyer of the Albanian People) and Die Albanische Korrespondenz (The Albanian Correspondence). The extermination policy, which, according to Trotsky, was implemented in the attempt “to correct ethnological statistical data that was not in their [Serbians’] favor,” was carried out throughout the years between the two world wars. However, the repressive policy culminated in 1938 with the signing of the Yugoslav-Turkish Agreement on the deportation of 400,000 Albanians to Turkey, preceded by the anti-Albanian doctrine of Serbian historian Vasa Çubrilovic entitled “Iseljavanje arnauta” (The Expulsion of the Albanians).[46] With the implementation of this policy, Belgrade aimed to shatter the Albanian ethnic compactness of Kosovo. The Serbs, whose goal was to employ the Nazi model of persecution against the Jews onto Albanians, reasoned that the world was too preoccupied with its own troubles and that the expulsion of Kosovo Albanians from their homeland would not be any country’s concern.

“At a time when Germany can expel tens of thousands of Jews and Russia can shift millions of people from one part of the continent to another, the evacuation of a few hundred thousand Albanians will not set off a world war”[47] Cubrilovic maintained in the memorandum “The Expulsion of the Albanians,” which was presented in Belgrade on March 7, 1937. The Albanians in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia were denied fundamental rights; they had no right to education, to books, newspapers or radio programs in the Albanian language, nor the right to merely declare themselves Albanians. In order to minimize their number, Albanians were forced to declare themselves as Muslim or Turkish. Therefore, it is not difficult to understand why the official statistical data of this period shows an artificial several-folds higher number of Turks. Another Serbian author, Vladan Djordjevic, in his book “The Albanians and the Great Powers”[48] did not manage tocontrol his hatred towards the community, and spat his venom openly. Indeed, in 1913, he went as far as to ask the Great Powers to allow the Serbian army to exterminate the Albanians from the face of the earth. He reasoned that they were “an inferior race with a tail.”

The Anti-Semitic press and anti- Semitic legislation of the Yugoslav Kingdom

Soon after the Serbian conquest, some of the Jewish population immigrated to Turkish territory. They were no doubt aware that the Serbs had traditionally regarded the Jews in Ottoman territory as adjuncts to Ottoman rule, and had often given them the same harsh treatment meted out to Islamism in the territories they conquered. According to Malcom, there had also been anti-semitic legislation in Serbia, rescinded only after Western diplomatic pressure in 1889.[49] In parallel with the persecution of Albanians and their deportation to Turkey, a discriminatory political discourse towards the Jewish community also prevailed in the Yugoslav Kingdom of the 1930s, sustained by the press and anti-Semitic legislations. A typical example is the Belgrade-based daily newspaper Vreme[50], a pro-government press company, according to which the Jewish community was a “closed and well-organized community, which strived solely for its interests, while exploiting and endangering the majority of the population.”

The Albanians of Kosovo and Macedonia were also approached and treated likewise. While the highest level of anti-Semitic climate was reached in the writings of Dimitrije Ljotic, who led the fascist party “Zbor”[51] between 1935 and 1945, the anti-Albanian climate was being installed by the fascist doctrine of Cubrilovic. The Nazi Germans must have been extremely excited by the fact that the Belgrade government had issued two anti-Semitic decrees as early as October 1940. Six months before the Nazi invasion of Yugoslavia, the members of the Jewish community were banned from producing and distributing food, while their enrollment in universities and high schools was restricted. Albanians were made equally vulnerable by the denial of their right to public and official use of the mother tongue, as well as the denial of being educated in the Albanian language at any level. As it was the case with the Jews, Albanians had their rights restricted in schools, universities and the public administration. Ironically, an identical policy was reinstated in Kosovo in 1989 by the Milosevic regime, which at the time made clear that it would be a case of ethnic cleansing.[52]

“The house of God and the guest”

Albanian historiography has not yet fully shed light on the protection and rescue of Jews by Kosovo Albanians, while Serbia has politicized historiography containing often forged information. Additionally, with the exception of a few recent attempts, neither the sheltering of the Jews has been given the deserved attention by Albanian historiography, although numerous events and cases related to the sheltering of Jews persecuted during World War II in Albanian households are embedded in the historical memory and narratives of Kosovo Albanians. An admirable achievement in this direction is that of the Institute of Spiritual and Cultural Heritage of the Albanians in Skopje, which has recently established a Holocaust Education and Research Department and published several works focusing on the contribution of Kosovo Albanians in saving members of the Jewish community.

The surviving Jews’ memories about Albanian solidarity

It is an undeniable fact supported by archival data that it was quite likely for Kosovo Albanians – who for decades had neither a state, nor any national institutions, and were even denied their fundamental rights – to sympathize with the local Jewish community. Likewise was the likeliness of showing solidarity and collective commitment for the protection of the members of the communities coming from different territories of the Balkans, whether Serbia, Macedonia, Croatia or elsewhere.

During World War II, when most of southern Kosovo was occupied by the Italian troops and administered directly by the Tirana government, Italy was forced to surrender the northern part of Kosovo – Mitrovica, Vucitrna and Podujeva – to the German protectorate of Serbia.[53] Due to the relatively positive climate predominating the Albanian territories controlled by the Tirana government, Albanians from Kosovo and Skopje rescued many Jews from Serbia and Macedonia and took them to Kosovo and Albania regions under the Italian occupation. In the northern part, which was controlled by the Nazi forces and where the Serbian chetnik units operated, Jews and Albanians were persecuted alike. “The north was surrounded by countries under Nazi occupation and there was no escape,”[54] writes the mother of survivor Ita Bartuv in her autobiographical book.

Unlike other regions, the Kosovo of the time was not characterized by an anti-Semitic climate, nor had any anti-Semitic legistation been enforced. The Jews there were not forced to wear distinctive signs and symbols. However, as in any community of the time, there are a few isolated cases of Jews being persecuted and interned, in comparison to the numerous anti-fascist Albanians sent to labor camps. It was not uncommon for local Albanian authorities to disobey the Nazis’ requests to submit lists of Jews, as in the case of the two representatives of the Jewish community, Rafael Jakohel and Mateo Mathatia.

It is an undeniable fact that in Kosovo and other Albanian regions, which until the outbreak of World War II were victims of brutal Serbian oppression and persecution, there was no anti-Semitic legislation or spirit. The level of empathy of Albanians towards the Jewish community also reflected the attitude of King Zog,[55] who approached Jews with great sympathy, and that of the government of Tirana,[56] which administered most of the territory of present-day Kosovo as part of the Italian occupation.

The stories of surviving Jews help us understand their situation in the Kosovo of World War II. Yaffa Reuven Née Bachar who, at the time was thirteen, fled with her family from Pristina to Shkodra. She remembers: “…when we arrived in Pristina, the Shkurti family welcomed us and we found shelter there. Every time the Germans appeared in town, they would warn us and hide us outside the city until the difficult situation passed, when they would return us home.”[57]

Previously unknown and impressive facts about the hospitality of Albanians are revealed by Mimi Kamhi Ergas-Faraji. In his memoir My Life under the Nazi Conquest, Faraji relates the experiences of his family and the role of the Sylejmani family from Ferizaj in rescuing and protecting them until they reached a safe destination. “After a few months of a quiet, suddenly the city (Shkup) was invaded by Serbian Jews on their way to Kosova. The south of Kosova was occupied by the Italian troops, being the only place to seek safety. The North was completely surrounded by the countries under Nazis occupation and there was no escape”[58] would Mimi Kamhi Ergas-Faraji write in his diary.

The transferring of Jews from Tetovo, Struga, Dibra and Kosovo to the territory of present-day Albania was assisted by the local Albanian authorities in Kosovo, who issued false ID-s that enabled the members of the Jewish community to move without trouble in case of a Nazi administration search. The rescue of dozens of Jewish families from Macedonia – which had first moved to Kosovo and then to Albania – was possible thanks to the courage of Albanians who had kinships in Kosovo and Albania. This was also the case of Veli Meliq’s family from Hani i Elezit, who rescued 17 members of the Frances family. According to the account of Johana Jutta Neumann, a Jew from Hamburg, Germany, after the occupation of Yugoslavia by the Nazi troops, nearly 200 Jews crossed into Kosovo, and from there into Albania.

Things got especially difficult after the capitulation of Italy and the occupation of the country by the Nazis. The chances of succeeding were much lower. In the Albanian environment, even under these circumstances, national pride had bigger appeal than the tendency to endorse anti-Semitism. It is worth mentioning a document issued by the Albanian state in relation to a robbery committed by two Jews in Pristina. The local Albanian authorities did not agree with the Nazi occupation’s orders to hand over the two Jews, stating that it was “the competence to take of any measure against them belonged exclusively to the Albanian authorities.”[59]

There is a long list of documents in the National Archive of Albania that debunks the claims of the Yugoslav communist historiography which allude that the Jews were also persecuted in Albanian territories. These documents ascertain the opposite; that is, the Jews were persecuted in the north of Kosovo, which, as previously stated, had been annexed to Serbia by the Nazis and was under the direct control of the Serbian General Nedic. It is also well-known that the Jews located in this area were sent to the Nazi camp of Belgrade or elsewhere. Nonetheless, several Jewish families, like the one of Shaul Gattenyo, escaped the “trains of death” thanks to the help provided by Albanians, both in Kosovo and Albania. As proved by documents found in the State Archive of Northern Macedonia and recently published by the Institute for the Spiritual and Cultural Heritage of the Albanians in Skopje, many Jewish families that were targeted by the anti-Semitic legislation of the Bulgarian state[60] managed to survive by escaping to the areas inhabited by Albanians.

Undoubtedly, the greatest credit for the assistance and relocation of Kosovo Jews to inland Albania belongs to the mayors of Prishtina, Riza Drini and Hysen Prishtina. Preng Uli, the mayor, and the doctor Spiro Lito convinced German authorities that Jewish prisoners had typhus and it was necessary to send the Jews to hospitals in Albania to avoid an epidemic. The Jews were taken to Berat given false documents and spread around Albania.[61]

In order to save Jews from the mass extermination imposed on them by the Nazis, the Albanian doctors and judges of Kosovo sent several members of this community to Albania— for “medical treatment” and other justifications. According to archival documents of 1943, it was officially announced that the local administration of Gjakova also assisted the Jews by issuing false ID certificates. The activity of the local administration, which openly challenged the authority of the occupying party, could not have been carried out without the support of the Albanian civilian population of Kosovo. Similarly, the local administration of Pristina strived for the rescue of the Jews by implementing the instructions of the Tirana government.

In 2014, six decades after the end of World War II, an elementary school in Berlin was named after Refik Veseli, the Albanian anonymous hero who saved numerous Jews that had reached the Albanian territory after escaping from the former Yugoslavia.[62]

The Albanian families that nobly risked their lives to contribute to the rescuing of Jews were numerous. It was this special connection forged in a dire situation that would pay off about six decades later. The Jewish children in the diaspora and in Israel alike would come to the aid of the Albanians during their most difficult times: the war of Kosovo, the subjection of Albanians to a “biblical wave” of expulsion, comparable only to the deportations of the Jews during World War II. In the face of the Nazi persecution, Albanian friendship and hospitality surely “had the effect of a panacea”[63] for the wounded souls of the members of the Jewish community. It goes without saying that Albanians in Kosovo and elsewhere are proud that their community helped, protected and saved numerous Jews. Their humanist approach and the solidarity for the Jewish community once more shed light on the traditional multi-religious and multiethnic coexistence in Kosovo.

In spite of any misinterpretations, the exceptional attitude of Kosovo Albanians towards the Jewish community should be considered within the context of the solidarity expressed by the Albanians in Albania, as the reference is to a people that share the same culture, identity, values and traditions. Therefore, it is no coincidence that the members of the Jewish community of various regions sought refuge in Kosovo and Albania. The mutual solidarity of Albanians and Jews was also nurtured during their coexistence under the imperial Ottoman administration.

Albanians are one of the few European peoples who could not subscribe to religious prejudices and religion-based antagonism. The reason for this may lie in the fact that Albanians themselves belong to three religious beliefs: Islam, Catholicism and Orthodoxy. As a consequence, no anti-Semitic sentiment could be sustained in the political culture of Kosovo, or its society in general. Due to the commitment of Muslim and Christian Albanians alike, most of the Jews of Kosovo survived the Italian and German occupation. Unfortunately, the Jews have suffered more in the northern part of Kosovo administered by Milan Nedic— is was annexed by the Germans, along with the quisling Serbian government. Also due to the assistance of the Serbs, about 200 Jews from the city of Mitrovica were sent to the Nazi camp of Belgrade or elsewhere. The British historian Noel Malcolm and American historian Bernd Fischer notes that this Albanian division had surrendered 281 Jews to the Germans, who were then sent to the concentration camp in Germany, in Bergen-Belsen near Hannover.[64] Samuilo Mandil was a Jew from Belgrade escaped to Albania during World War II[65]. He is one of the first authors to address the issue of rescuing Jews from Albanians during World War II. He published the article “Israelis in Albania: before the occupation, during the occupation and after the liberation by the occupier” in the Tirana newspaper “Bashkimi” (February 20, 1945). He had fled from Belgrade to Berat in 1942, where he had taken refuge. Mandil mentions a very intense case that in 1942, a number of 53 Jews were arrested in Mitrovica[66] and handed over to the Nazis.[67] This can be understood as the fact that it happened in March of last year.

Traditionally, Yugoslav and especially Serbian communist historiography has manipulated figures and lists of Jews interned in Kosovo during World War II. That it was a matter of a manipulated number and list, this is confirmed by the findings of the French researcher Claire Lavone who specifies that of the 530 persons arrested and sent to Berg Belsen, 90 percent of them were communists, partisans, Albanian political opponents, Montenegrins, Serbs, Macedonians, while the rest were Jews.[68] Also based on documents in the Central Archive of Albania only 34 Jews were sent to labour camps in Germany,[69] and not as Yugoslav communist historiography claimed that the number was around hundred people. From the list of persons to be escorted by the SS Skanderbeg[70] Division, some authors had listed as missing the Jews who had in fact taken refuge in Albania, he claims.[71]

Since Tirana was the main administrative center during the war, the archival documents are collected also in the State Archive of Albania (AQSh) and these documents prove that the fate of the Jews of Kosovo during the Second World War (WWII) can not be separate from the fate of the Jews during the old royal Albania. In this sense, the view that there were two different Albanian attitudes from Albanians towards Jews, one in Albania and another in Kosovo does not stand

The ancient code of “Besa”

But why did the Albanians show solidarity with the Jews, while elsewhere in Europe they were the subject of persecution? The answer to this question can be found in the ancient Albanian code of honour, promise and hospitality. In Kosovo and Albania, there is no law on not crossing the courtyard door or“trespassing,” as the Americans say. There is another law: promise, hospitality, friendship. “The house of the Albanian belongs to God and his friend,”[72] as noted by ancient Albanian word. Norman Greshaman, a well-known Jewish-American photographer, in the movie “Besa-The Promise” states the following: “Albanians do not have that much to export, but they have a unique product in the world: the Albanian promise.”[73]

According to this code, when someone is offered hospitality and promised protection, it is to be respected regardless of the risks. Still according to the Albanian traditional code, if someone is offered help or if he is hosted at an Albanian household, then the house of the host is considered “the house of God and the guest.” This element is valued and recognized worldwide as the traditional practice that saved the lives of the many members of the Jewish community.

Another element that is frequently and rightly considered to have shaped the approach of Albanians to the Jews is their characteristic inter-religious tolerance. The renowned Canadian historian Bernd Fischer maintain that while “other countries in the Balkans and the rest of Europe institutionalized discrimination and participated, either passively or enthusiastically, in one of the greatest crimes against humanity – the persecution of the Jewish population – Albanians, often well aware of the risks, opened the doors of their country and also their homes. And not only to the local Jews, but to Jews of other countries. Nothing speaks more to the noble spirit of the Albanian people than this.”[74]

The hospitality Albanians reserved for the Jewish has been widely esteemed, primarily from this community, although very little has been written about this issue. The contribution of Albanians was considered with the same regard as that of numerous Kosovo families who risked their lives for the noble mission of providing shelter to many Jewish families.

Kosovo and the support of the Jewish diaspora and Israel

The notion that history repeats itself seems to be true. At a time when Kosovo Albanians faced the risk of being exterminated by the Milosevic regime, the Jewish people eagerly protected them. This was perhaps rooted in the empathy of the Jewish community towards the sufferings of the Kosovo Albanian refugees. Although the communists of Yugoslavia, similarly to their counterparts all over Eastern Europe, had proclaimed that the socialist system was the model to be followed for the resolution of nationalistic issues, Albanians were in a dire situation during the two decades following WWII. The state of emergency implemented throughout Yugoslavia until 1948 was extended in Kosovo until the mid-1960s. The champion of repression and brutality against Albanians was the Yugoslav Minister of the Interior, the Serbian Aleksandar Rankovic of extremist nationalistic beliefs, who continually terrorized Albanians by making use of Stalinist methods. In Kosovo, the years between 1947 and 1966 are remembered as “the Rankovic era.” During this period, Kosovo turned into a police state. Countless Albanians were executed or disappeared in the prisons of the Yugoslav secret police, while hundreds of thousands more were deported to Turkey or fled to the West.

It became obvious that even under the socialist rule and the proclaimed equality of nations, the anti-Albanian doctrine would go unpunished. In fact, at the beginning of the 1980s, it would be revived. The anti-Albanian policy culminated with the appearance of Milosevic on the political scene, and the removal of Kosovo’s autonomy. At the gathering of the Slovenian intellectual elite “Cankarjev dom” on February 27th, 1989, president Jožef Školč of the Alliance of Socialist Youth of Slovenia compared the Albanian experience to that of the Jewish community during World War II. It was the time when Yugoslavia was moving towards disintegration, primarily because of the Serbian plans to create a centralized Yugoslav state controlled exclusively by the Serbs.

This was one of the most difficult periods in the history of Kosovo, marking the beginning of the internationalization of the Kosovo issue. Those who held senior positions in the U.S. administration were the main spokesmen in U.S. and NATO involvement in the Balkan conflict, voicing concern about developments in the region.[75] The emerging of this issue in Washington’s offices owes, first and foremost, to the extraordinary and decisive commitment of two American congressmen of Jewish descent: Tom Lantos, a Holocaust survivor, has been a member of the U.S. Congress since 1981. He has consistently been a supporter of the Albanian cause, in support of its full independence from Belgrade since the establishment of its international protectorate in 1999.[76] Congressman Eliot Engel is an equally influential figure in US politics. Senior official in the U.S. administration during this period was Wesley Clark, holding the rank of General of the U.S. Army and Supreme Commander of Operation Allied NATO from 1996-2000. He originates from a Jewish family from Belarus which experienced the Russian pogrom. Robert Gelbard is another U.S. diplomat of a Jewish origin, who served as ambassador to Bolivia and Indonesia. In this period, during military intervention in Kosovo, William Cohen was Secretary of Defense. His father was a Jew (his mother Irish) who had emigrated from Russia. During the Iraqi and Kosovar wars, he was a proponent of important activity. A precious personality with an extensive political career – he also served as a member of the US Senate – President Clinton appointed him to his cabinet, although he came from the Republican Party.[77]

Thanks to their dedication, Kosovo was in the focus of the administration of President George H. W. Bush senior and especially that of President Bill Clinton, who entrusted the chief position of American diplomacy to a lady of Jewish descent: Mrs. Madeleine Albright.

In 1998-99, when it seemed as if the events of the Bosnian genocide would be repeated, the Kosovo tragedy acquired global proportions. The deportation and mass killing campaigns implemented by the regime of Milosevic and his statements were fashioned after Hitler. Declaring in front of Western officials that “he could walk on the corpses of Albanians,”[78] he made the Serbian policy reprehensible for everyone. The carnage could not be ignored: the images of the persecution of Albanians, their expulsion by all means of transportation, and their marching were reminiscent of the images featuring the expulsion of Jews during World War II. Moshe Peretz, a Holocaust survivor, claimed: “I’m reminded of what I went through in World War II in Russia and Poland. After I watched this, I couldn’t sleep at all. It was exactly the same thing.”[79]

“The Evil must be opposed …”

Besides Mrs. Madeleine Albright, former US Secretary of State, many other personalities of Jewish descent raised their voices, including the likes of former NATO Supreme Allied Commander General Wesley Clark[80], Dayton architect Richard Holbrook, Holocaust survivor and writer Elie Wiesel, philosopher Andre Glucksmann, former president of Israel Shimon Peres, the famous writer Amos Oz, Hyman Bookbinder, Deborah Dwork, Anna Cohen, as well as author and professor Daniel Goldhagen. The american advocates were well-aware that, as the Shoah (Holocaust) and the doctrine stipulated, the protection of human lives was a significantly greater responsibility than the issue of a state’s sovereignty. Large number of Jewish personalities have reacted against the systematic violation of human rights in Kosovo, and have opposed the inhumane Serbian policy exerted against Albanians in Kosovo in the late twentieth century. Second, Jews considered identification of the expulsion of Albanians from their lands, as similar with anti-Semitism, of course, smaller but similar to Jewish exodus.

Since the United States and its NATO allies began military intervention in Kosovo last month, representatives of American Jewish organizations have spoken out strongly in support of the action. American Jews – like most other Americans – see the Serbs as villains who are engaged in ethnic cleansing of Albanians, just as the Nazis engaged in ethnic cleansing of Jews. TV images of helpless, homeless Albanian refugees have brought the world to tears.[81]

Past historical experience had taught them that evil should not be underestimated; it must be opposed. Madeleine Albright, born in the Czech Republic and traumatized by the Munich Agreement and the collective persecution of Jews, is rightfully considered as one of the greatest proponents of the humanitarian intervention doctrine. The appeal of Nobel Peace Prize laureate Elie Wiesel, survivors of the Auschwitz concentration camp, and other personalities of Jewish descent were crucial for the US political and military engagement in the Kosovo war. The Shoah conclusions justified the military intervention of NATO member states in Kosovo in 1999. Wiesel expressed his whole-hearted support for the NATO bombing, stating, “…if the world had reacted (during World War II) the way we are reacting now, many tragedies would have been prevented.” Organization by organization, the mainstream Jewish community has declared its support for NATO’s intervention in Kosovo, frequently citing parallels to the Holocaust. Some compare Serb leader Slobodan Milosevic to Adolf Hitler”.[82]

Wiesel’s Kosovo message was consistent in his recent writings: he supports NATO’s initiatives, and Milosevic must be stopped. “If we see governments doing something, we as individuals will do something,” he said.[83] But, as a death camp refugee, Wiesel would not equate the reputed ethnic cleansing of Albanian Kosovars with the Holocaust and Nazi Germany’s policy of exterminating Jews. “I am against comparisons because I have learned that everything is unique,” he said. “My advice is not to compare. Every suffering is unique. This situation demands action, not comparison”[84].

It is speculated that Secretary Albright and President Clinton drafted General Short’s air campaign against Serbian military targets after the Serbian forces perpetrated the massacre of Reçak in January 1999. For this reason journalists baptized the Kosovo war as the “Madeleine war.” The motives that prompted this American politician to defend the threatened Albanian people in Kosovo are found in her biography. During her childhood, her family was the victim of dictatorial policies twice: the first time was when Hitler invaded Czechoslovakia, the second when Stalin’s troops occupied Hungary. Therefore, Albright considered Milosevic a “criminal” who should be given several blows to “clarify his mind.” The Washington Post elucidates on Albright’s stance, underlying that “the Secretary believes deeply that Adolf Hitler and other tyrants could have been deterred if confronted early”. She applied that view to her diplomacy in confronting the dictatorial regime of Milosevic, a regime that in March-May 1999 alone expelled nearly 80 percent of Kosovo’s population and executed some 12,000 Albanian civilians.

John G. Stoessinger, also a scholar of Jewish origins, maintains that “The intention was to cleanse Kosovo of Albanians in order to provide a lebensraum for Serbian settlers.” He notes that “Adolf Eichmann, the man in charge of deporting Jews during the Nazi regime, would likely have appreciated the scale of Operation Horseshoe.”[85] Maintaining that the case of Kosovo was different from the Holocaust in scale, the well-known American historian Daniel Goldhagen claims “both Hitler and Milosevic commenced their crimes in the name of an ideology that undervalues the lives of others and is based on the idea that people have the right to kill others if they get in their way.”

Israel and Kosovo

During the Kosovo war, when some Arab and Muslim countries supported the “Butcher of Balkan,” Israel – along with the Jewish diaspora – defended the Albanian population expelled from Kosovo and condemned the Serbian ethnic cleansing campaign, supporting the NATO military intervention against Serbian military objectives. The country provided more support and assistance than any other country that was not a NATO member.

In addition to humanitarian aid for the Kosovar refugee camps in Albania and Macedonia, it is also the case of aid within the state of Israel. With the exception of Turkey, Israel is the single Middle Eastern country to have sheltered Albanian refugees from Kosovo. In April 1999, the Israeli Foreign Minister declared that his country would provide humanitarian aid to Albanian refugees from Kosovo. The Minister proclaimed full support of the NATO and US efforts to end their persecution. In the same spirit, the Israeli government condemned the Serbian campaign of ethnic cleansing in Kosovo, appealing for its immediate end.

Israel was enthusiastically holding telethons, rallies and fund-raising drives in support of Kosovo Albanian refugees. Six planeloads of food, tents and other supplies have been dispatched and a 100-bed field hospital set up in Macedonia, which has sheltered many refugees.[86] Israel also accepted an initial group of 100 Muslim refugees, giving them the same financial aid package that immigrating Jews received.[87] While hundreds of thousands of Kosovo Albanians had sought refuge in camps just outside the borders of Kosovo, a few hundred more had made their way much farther from the burning Kosovo— to outside countries that had agreed, at least temporarily, to host refugees. On April 12th, 1999, planes bearing about 100 ethnic Albanians each landed in Israel and Norway, where they had been welcomed with open arms.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and his wife, Sarah, were on hand in Tel Aviv for their arrival, greeting the refugees on the eve of Israel’s annual day of remembrance for the 6 million Jews exterminated in the Nazi Holocaust.[88] “You are arriving on a special day for the Jews of Israel,″ said Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, greeting the 114 refugees – 17 families – on the tarmac.[89] “As Jews, we have a special sensitivity for the suffering of others. When we see the cars, tractors, trains or the convoys of marching refugees, when we see the faces of frightened children and tearful mothers, we feel a responsibility to help.″[90]In his speech Netanyahu declared: ”Israel condemns all mass murder, committed by the Serbs or by any other element,” he said. ”We condemn it because of our history and our moral view.”[91] Moreover, when asked his position on the NATO campaign, he made clear: “We stand behind the effort, the effort of NATO and President Clinton to end this tragedy.”[92] In this context, former director-general of Isreali Foreign Ministry Shlomo Avineri said in an interview: ”You can’t be neutral between a murderer and his victim. That’s the criticism that we, as Jews, as Israelis, have always leveled at foreign nations, including the Swiss.”[93]

Kosovo and Israel established diplomatic relations

Coincidentally, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu was the protagonist of the most recent international recognition of the state of Kosovo, 21 years later. This recognition has special and historical significance for both states, which share common orientations, allies, values and interests. The agreement signed at the White House[94] is short of the full diplomatic recognition that Kosovo seeks, the recognition that the Trump administration and the European Union have both worked to achieve.[95] Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu issued a statement welcoming the agreements: “First country with a Muslim majority to open an embassy in Jerusalem. As I have said in recent days, the circle of peace and recognition of Israel is widening and other nations are expected to join it.”[96] Belgrade, which in 2011 had voted for the membership of Palestine in UNESCO, was not pleased by Tel Aviv’s decision. But as the Israeli ambassador to Belgrade stated, “the recognition of Kosovo is a done deal.”

Based on the Principles of the UN Charter and in compliance with the Vienna Convention on Diplomatic Relations of 1961, the agreement on mutual recognition between the Republic of Kosovo and the State of Israel is particularly significant for both countries, as the reciprocal recognition paves the way for an effective partnership between the two. Considering the experiences of the two people and the way the state of Israel and the state of Kosovo were established – mostly owing to the decisive support of the US – the recognition agreement holds strategic significance for its establishment of diplomatic relations between Kosovo and Israel. Some media reports suggested that Israel’s recognition of Kosovo was not yet in effect and would be formally declared “in the coming weeks.”[97] However on September 21st the Israeli ambassador to Serbia, Yahel Vilan, confirmed that Israel had in fact recognized Kosovo on September 4th, 2020: “There is no doubt whether Israel will recognize Kosovo or not, because Israel already recognized Kosovo on September 4th.”[98] Even if Vučić did not appreciate the statement of Ambassador Vilan, the recognition of Kosovo is indeed a done deal.

Yonatan Touval, an analyst at the Israel Institute for Regional Policy, says in an interview with Radio Free Europe that Israel’s recognition of Kosovo,[99] 12 years after the declaration of independence, comes at a time when views that independence does not provoke feelings are dominant. “I think that these anxieties, these worries about this imaginary parallel between Kosovo and Palestine have been significantly alleviated over the past 12 years. For these 12 years, since Kosovo declared independence, history has shown that it has not had a negative impact on [Israel’s] conflict with the Palestinians.”[100]

Five months after the recognition, the two countries finally formalized the establishment of diplomatic relations. The official (virtual) signing of the diplomatic relations on February 1, 2021 between the Minister of Foreign Affairs and Diaspora of Kosovo, Meliza Haradinaj-Stublla, and the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Israel, Gabriel Ashkenazi[101], marks a historic moment for both countries: for Kosovo it represents a key step on the path towards further consolidation of statehood and its international subjectivity, while for Israel it’s the commitment of the Kosovar side to open its embassy in Jerusalem.[102] Following the American example legitimizes the recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel. In this line Ashkenazi, who noted that it was the first time two nations had established relations over cyberspace, thanked the United States for its efforts “to promote peace around the world,” calling the establishment of diplomatic relations between Kosovo and Israel “yet another important, exciting, and historic step.”[103]

Minister of Foreign Affairs and Diaspora, Mrs. Meliza Haradinaj-Stublla, stated that the establishment of diplomatic relations with Israel opens a new historical chapter between both states. “On this important day we open a new chapter in historical relations between our countries, the existence of the people and statehood of which has been challenged. Our states have been close to each other in most difficult times and today we start a journey as two states,” stated the Head of Kosovar Diplomacy,[104] adding that Kosovo and Israel share a “Historic bond” and had both “witnessed a long and challenging path to existing as peoples and becoming states.”[105]

In fact, the recognition by Israel and the opening of the Kosovo embassy in Jerusalem reveal the vital importance and influence of the United States in the foreign policy of these countries, which existentially owe their support to the United States.[106] These relations mutually serve both countries, the consolidation of their regional and international positions, as well as the American foreign policy itself. This position is also clear in the statement of the US State Department: “When our partners are united, the United States is stronger,” describing this event as “a historic day.”[107] Kosovo-Israel relations also add an important dimension to the wider US-mediated agreement between Kosovo and Serbia. These relations between Tel Aviv and Pristina in the context of geopolitics promote peace and stability in the Balkans and the Middle East.[108] At the same time, the establishment of Kosovo-Israel relations has a significant impact on the EU, and shows a diplomatic superiority of Washington over Brussels. If the Americans managed to convince Tel Aviv to recognize Kosovo and confirm that there is no parallel with Palestine, Brussels did not succeed. Nor was it determined enough to convince its five members – Spain, Greece, Slovakia, Cyprus and Romania[109] – for the recognition of Kosovo, even 13 years after its declaration of independence and the decision of the ICJ. The issue becomes even more sensitive due to the fact that Brussels has continued since 2011 to mediate the dialogue for the normalization of Kosovo-Serbia relations. European disunity in the field of foreign policy has weakened its power in the eyes of Kosovo and Serbia.[110]

While this recognition of Kosovo by Israel is being considered as one of the most important in the last decade, reactions from abroad have been various. For the USA administration, the establishment of diplomatic relations between Kosovo and Israel is considered a historic day, while the EU has not welcomed such a development, especially concerning the opening of the Kosovo Embassy in Jerusalem.[111] However, such an attitude has been ignored in Kosovo, as Prishtina considers that Brussels has done little in the process of European integration, and has left Kosovo isolated as the only European country without visa liberalization. But it remains to be seen how the EU will react when it comes to relocating Serbia’s embassy, which has opened talks on EU membership.

On the other hand, the new administration of U.S. President Joe Biden applauded the Kosovo-Israel agreement as a “historic day.” “We think that Israel normalizing relations with its neighbors and other countries in the region is a very positive development, and so we applauded them, and we hope that there may be an opportunity to build on them in the months and years ahead,”[112] said recently confirmed Secretary of State Antony Blinken. In this line was also the statement of the Spokesperson of the Department of State, Ned Price, said the United States of America will stand by Kosovo as it continues to move forward in its Euro-Atlantic path. Price underlined “The United States congratulates Israel and Kosovo on formally establishing diplomatic relations. Yesterday was a historic day. Deeper international ties help promote stability, peace, and prosperity in both regions. When our partners are united, the United States is stronger. The United States will stand by Kosovo as it continues to move forward on its Euro-Atlantic path.”[113]

However, the EU addressed criticism of Kosovo’s plan to open an embassy in Jerusalem as the two countries signed an agreement on establishing diplomatic relations, recalling the bloc’s position on the issue in line with a UN Security Council resolution. EU spokesperson Peter Stano said that the EU position is exactly the same as it was when this question was asked last year after the signing of the agreement between Kosovo and the Trump administration on September 4th, 2020.

“This decision is diverging Kosovo from the EU position on Jerusalem,” said EU spokesperson Peter Stano. He pointed out that all embassies of the EU countries in Israel, as well as the EU delegation, are located in Tel Aviv, based on the corresponding UN Security Council resolutions and European Council decisions.“[114]

He underlined that Kosovo, through this, is undermining its path towards EU integration. “Kosovo has identified EU integration as its strategic priority. The EU expects Kosovo to act in accordance with this commitment so that its European perspective is not undermined,“[115] Stano emphasized.

But on the other hand, many Kosovars asked what could be the consequences for Pristina, as well as what prompted the EU to ask Kosovo to honor its commitment while it is not recognized by five EU countries, and therefore cannot become an EU candidate or be granted visa liberalization.

The establishment of diplomatic relations and the recognition of Kosovo by Israel has not been well received by either Serbia or the Arab League, which condemns Kosovo’s opening of an embassy in Jerusalem. Serbian President Vucic warned that the agreement with Israel could hurt future ties.[116] Meanwhile the Arab League Secretary-General Ahmed Aboul Gheit has condemned, in the strongest terms, Kosovo’s recognition of Jerusalem as the capital of Israel, and its decision to open an embassy in the city under occupation. In a statement he stressed that the Kosovan decision violates the international consensus regarding the opening of embassies in occupied Jerusalem.”[117]

Kosovo and Albanians could learn a lot from the state of Israel

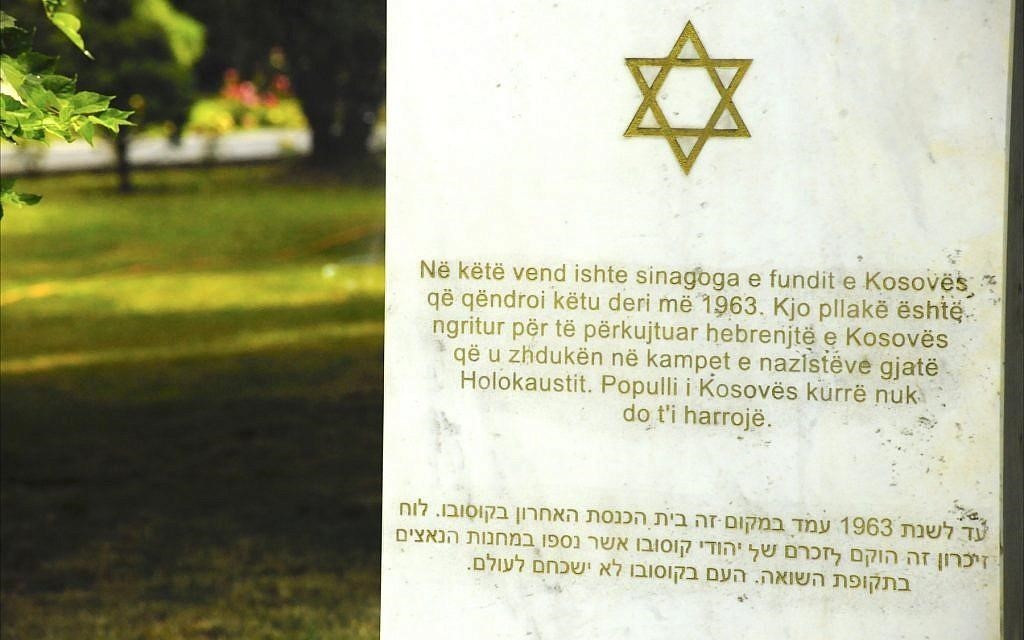

The journey of the Jewish community has been one of suffering and sacrifice. The same is true for Kosovo Albanians, who, during the twentieth century, were the subject of three exterminating expulsions. In this context, Kosovo could learn a lot from the state of Israel, not only in relation to security and the process of state-building, but in relation to the culture of memory. At the same time, the Republic of Kosovo should restore the historical and cultural values of the Jewish community of Kosovo, as a sign of respect for the history and contribution of the Jewish community there. In this context, the memorial in the capital of Kosovo – across the road from the Parliament of the youngest European state – marks a piece of the Jewish community history, as it commemorates the 92 Jews deported during World War II. The memorial plaque placed at the site of Kosovo’s last synagogue, which was destroyed by the Serb-Yugoslav communist regime in 1963, also honors Kosovo’s historic Jewish community.[118] The Museum of Kosovo should also dedicate a special sector to the Holocaust. Without the unmatched contribution of Jewish personalities in the field of Albanological studies, along with that of several members of the Jewish diaspora, publicly supporting the demands of Kosovo Albanians for independence, Kosovo’s journey to this point would have been impossible.

Kosovo should also follow the example of the Institute of Spiritual and Cultural Heritage of the Albanians (ISCHA) in Shkup/Skopje.[119] Scholarly publications in this field and the translated memoirs of Jewish individuals who survived the Holocaust would make a precious contribution for the clarification of the Jewish question in the Balkans. The decision of the Kosovar authorities to donate a building to the Jewish community is a step in the right direction, as it will be used as the Jewish museum[120] to display the history of coexistence between Albanians and Jews.

The future should be marked by more effort and commitment on behalf of scholars and various institutions to further their studies on the Jewish question, taking into consideration the survival of the Jewish community throughout centuries and the solidarity that other peoples have shown to them. That is, Albanians need to learn from the Jewish tradition of cultivating and archiving the communal memory. A perfect example is Yad Vashem– The World Holocaust Remembrance Center, which could be included in school curricula along the rich tradition.

Part of a marble monument on the grounds of Kosovo’s Parliament building in Priština — engraved in Albanian, Serbian, English and Hebrew — that marks the spot where Kosovo’s only synagogue stood until 1963. An inscription on the monument also honors Kosovar Jews who were killed during the Holocaust. (Larry Luxner/ Times of Israel)

Conclusion