by Ines Stasa

Introduction

With the regime change in Albania one of the main concerns was the upcoming constitutional and institutional design of the post-communist and a democratic-state-to-be. The transition in itself reflected over the thirty years since the replacement of the regime, the very contested and deviated path towards democracy and sustainability of political, social and economic development. This article seeks to bring at the forefront the inadequate approach, the lack of a proper model that would generate conceptions of political and moral responsibility, legitimacy and collective forces for state building – the ones that were missed throughout transitional politics in Albania.

The first part will examine the two well-known models of state-building, the Weberian approach under the ‘institutional approach’ and the ‘legitimacy approach’ to better understand the challenges, failures and transitional conception of Albanian politics in designing the post-communist state. The second part will identify and analyze the milestones of Albanian transitional state-building and seek to relate on the dynamics of its choices with the state of democracy since the replacement of the regime. On the other hand, there is to be recognized the very important role of party system and its transitional operating mode in dominating the scene of institutional and societal reforms over the years. The party system framework followed by its political culture legacy of the last, have contributed in hindering the process of building accordingly to the norms of democracy, the state institutions and legitimacy of the whole political process. The third part will conclude the argument and provide general remarks on the relationship between state-building and progress of democratic measures in Albania.

Models of state-building and state failure in Albania

Albania remains one of the less researched post-communist countries in the Eastern Europe and in the Western Balkans region. The difference of Albania and post-former Federation of Yugoslavia countries is still persistent in the regional politics and /or in international “intervention” in state-building projects. In contrast to other countries in the region, Albania is the one and the only that did not have the “pressure” of nation-building instead of that of a state-building. Even though Albanian leadership political discourse and the tendency to protagonist-size have been more dominant in the last 10 years, Albania had to deal only with the state-building process. The very real homework to be done by Albanian political actors was to create the environment where in the state would lie and build economic, social, political infrastructure where in the whole society would express and represent its common interests.

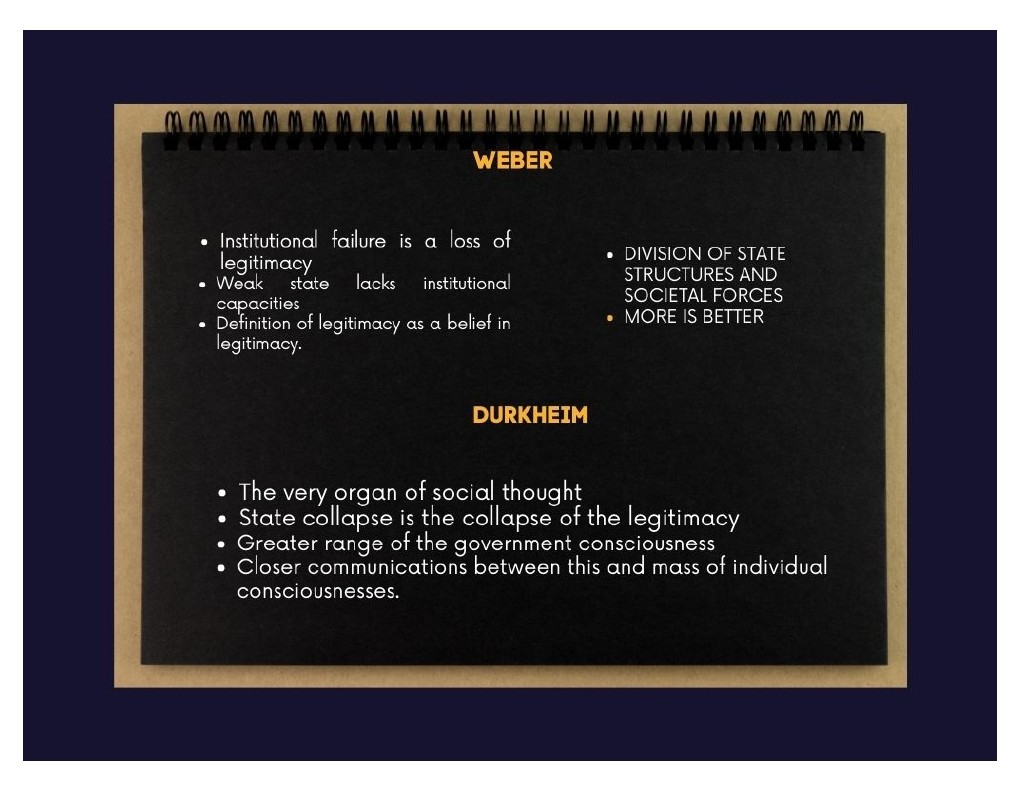

Durkheim (1957) argued that the state as a “special organ whose responsibility it is to work out certain representations which hold good for the collectivity” elevates its role through consciousness and reflection. In other words, the approach that Durkheim attach to the State is that of the very responsibility and the distinguished feature to deliberate in order to make citizens part of the process. The legitimacy approach of Durkheim considers democracy as a system of reflection, where in the key point does not rest upon the quantity of institutions rather on their ability to act on just terms and develop the individuality of each man. Apart of approaching institutions, deliberations and representation, Buzan (1983) bolds the idea that the state is not merely a set of institutions, but a logic that completes the totality of it. He further adds that “organizing ideologies are perhaps the most obvious type of higher idea of the state”. In this context, the state might identify with the varieties of ideologies and take their form of institutional structure. This logic brings us at the analyzing of what type of state have Albanians chosen to build after the 1989, as we take it as a world political event. It is a well-known fact that the political regime inherited in Albania was product of myths and propaganda, hence even the strength of the communist state was part of the mythology that dictatorship created to save its authority and legitimacy. We would not give a proper diagnosis on the state-building process after 1989, if we do not take into deep analysis the shape of state during communism; its power and authority; whether it had legitimacy and how is this an indicator to prove that Albanians were part or not of the dictatorship; and the most notably, the legacy of communism in political system. Two main schools of thought related to the State are the ‘institutional’ and ‘legitimacy’ approaches, represented by Weber and Durkheim. The clash of perspectives between their conceptions on State, leave us with the ‘duty’ to better contextualize and define our State as a matter of both set of institutions and of ‘social thought’. These two scholars complement each other in what a State should accomplish and deliver. It is not in the object of this article to extend the analysis on the two main schools of thought, rather than taking them as units of theoretical analysis to track the state building process in Albania. In order to provide basis for understanding the nature of state building in Albania – that differs essentially from other countries in the Balkans, I will mention two key areas in which Durkheim highlights characteristics of democracy, legitimacy and transparency. Durkheim does not refer implicitly to the transparency element of the State towards citizens, but he states that “because there is a constant flow of communication between themselves and the State, the State is for individuals no longer like an exterior force that imparts a wholly mechanical impetus to them”(1957, 91). This way of perceiving the sate uplifts the democracy in a ‘moral superiority’. For the sake of this article, I will put more efforts on the implications of the two schools of thought in order to contextualize state building in Albania. By evaluating the points of implications, therefore we reach to the points of failure/success of the process. Did the Albanian leadership follow one or the other model of the Statebuidling? Is legitimacy yet a myth and part of broader propaganda to save authority in a post-communist country? Where differentiate the model of Weber from that of Durkheim? How is the debate on State influenced by these two scholars? Weber is considered the starting point, while I would consider Durkheim a turning point in regard of State as a social thought, largely perceived as an ideal form of stateness and its relationship with the citizens. A form that even democracy as an ideological project has not been developed as much as to grant to the State the environment to reconstruct public authority.

*Figure elaborated by the author

Other scholars as Grimm (2019) emphasizes the importance and impact of consolidation of formal political institutions through legitimate political system, the one that requires much more effort than democratic elections or a new constitution. According to her perspective, the main focus in a state building process should rest upon ‘the understandings of socio-political order” as pre-condition for successful ‘installation’ of the so-called hegemonic model of intervention and state building. Once again, the case of Albania differs from other countries of region, and precisely for this uniqueness, the state building in post-communist countries represent different features of those in post-conflict settings. This Western approach mostly follows the Weberian model, thus, implications for a “one size-fits all” statehood paradigm no longer explains in depth the roots of post-communist state building projects. In other words, the idea of state is taken for granted, which does not allow for the legitimacy to be taken as a crucial symbol of the relationship of State and its citizens, or put differently, the dialogically approach of intra-connection between agencies.

What has gone wrong with the Albanian transition may be the main question that arises today at most of the segments of population, experts and transition scholars. One of the prominent scholars in Albania, Kalemaj (2020) has screened the early moments of Albanian transition in terms of rapid economic reforms, lack of political consensus for major national issues, legacy of lack of political culture and among many other concerns, the way politics operated and still operates ‘behind the wings. Moreover, what was to be done first and foremost in the early stages after the fall of the communism as to conduct a prompt process of breaking with the past and its institutional legacy. Of importance to shed light in this kind of analysis is to figure out the nature of State during communism and what did it mark in terms of institutions? Under what political and social conditions would the new institutions be built in order to fulfill the duty? Kalemaj highlights the fact that the lack of a consolidated civil society and the social withdrawing of the public from key issues, have turned transition in a ‘natural’ or normal way of operating and living (2020, 23).

Another concern is the continuing legalization of politics (the executive branch holds the largest number of law-proposals in the Parliament) rather than increasing participation of political community in the public topics, and the nature of technocracy that domestic issues have been interpreted and advanced. This has led to the decrease of trust of public in government and stagnation of legitimacy of political leadership. Among other post-communism scholars, Uvalic (2012) pays attention to the context of the Western Balkan countries after the 1989, reflecting on the wounds of dissolution of the Yugoslav federation and all the consequences that followed after that. Albania is considered as one of the early reform-oriented countries due to the fast speed of economic reforms taken in the name of ‘shock therapy’. The question that should be raised here is whether the fast speed of those early reforms hindered the process of state building and prolonged the state of democracy in a post-communist country which was fully isolated for four decades. Moreover, the rapid economic programmes, in concert with the political and institutional infrastructure of dictatorship, combined with the lack of elite competition, massive immigration, lack of dissidence and grass-roots movements, have motivated the highly political divisiveness among social groups and contributing to a lack of cohesion and reconciliation after the civil war history in 1943, followed by the class struggle during communism.

Following the end of 1945, international actors were more preoccupied for the State in its sovereignty and authority that would not be threaten by external forces, while on the other hand, the State approach today is more attached to the ‘good governance’ (Chandler, 76). As Chandler puts it, ‘good governance’ diminishes the linkage between social forces and the State, leaving in the shadow the importance of the process that state institutions strengthen their bonds with the people. It is stated that Albania did not undertake processes of nation-building as elsewhere in the region (Kalemaj 2009, 233), thus having more prospects for the democratization process to have success.

The fact is that after thirty years of the fall of communism, democratization and transitology are like those straight lines that do not intersect with each other. Both concepts are transformed into senses that public do not have the ability to differentiate. Debating our deficient democracy through the lenses of a transition that is still under-researched and highly politicized, an aim that was dreamt a lot after 1989 and still a myth because of inability and unwillingness of political leadership to conceive accountability, transparency, authority. For the sake of empirical research, I have collected here data from 3 Indexes, but what is to be pointed out is the necessity to pay more tribute to the processes rather than on static measurements. Hereby, both models of democratization and state building should be analyzed in depth for their focus on elements such as culture, behavior, attitude and elite competition. These dynamic measurements, often excluded by studies, represent the most defining nature of development in post-communist countries.

Another point to be raised in here is the legacy of the state-party model and the relationship of today’s political parties with the State structures and that of between political parties and citizens. The social contract of political leadership with its citizens is that of patronage and clientelism, in other words a rent-seeking behavior. Even though scholars of post-communist studies have concentrated their analyses on three pillars known as ‘triple transition’, they have ignored as a crucial element “the need to reconstruct public authority, or state building” (Grzymala 2002, 530).What scholars assumed was that the post-communist State should be reduced in size and scope due to its overwhelmed mode of operating and administrative structures. Part of the legacy and of continuity from prior regime style, is still the State as the largest employer within the system. Right after the entry into force in 2009 of the Association-Stabilization Agreement, the Albanian Government adopted the inter-sectorial Strategy 2009-2013. Governments afterwards continued to adopt Strategies of 2013-2015 and of 2015-2020.

Reports and assessments on Public Administration Reform are conducted from national and international non-governmental organizations. In 2014, a study-report on public administration in Albania and on relationship between politics and citizens, reflected some key interesting findings. Participants of the survey were asked to share their perception on the role of public administration. More than a half of respondents (56%) believe that their role is to “serve to the people”. Others (21%) believe that their role is to address citizen’s needs, or that is their duty to act as mediators and problem-solvers (19%). But what is the most striking evidence by this survey is the 2% of participants that believe their role is to serve to their personal interests. (Dhembo 2014, 31)

Author of this report, Mrs.Dhembo states that: “In general, during the last decades, the capacity to implement reforms has been weak and political interferences still remain a threat for the successful implementation. (2014,14)

Public administration reform is attached to the main areas of assessment in the EU’s enlargement policy, such as rule of law, economic governance and the functioning of democratic institutions. Thus, public administration reform contains aspects of institutionalization and legitimacy as we refer to the state building process. Its performance in delivering services, level of political interference, degree of public trust in the state apparatus, are part of the analysis to what extent the State legacy of communism transmissed its features to the post-communist state in Albania.

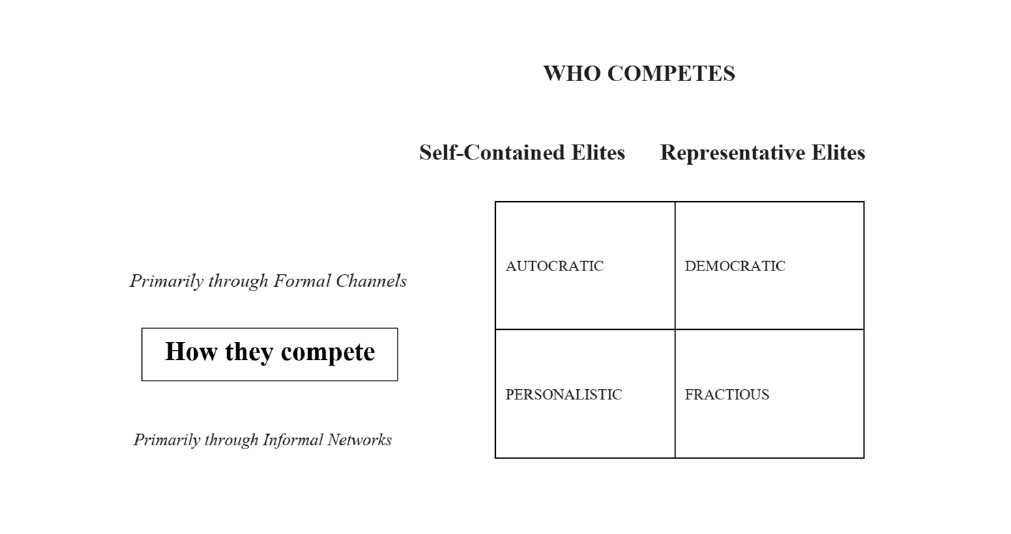

The rapid economic transformation shocked literally the whole part of the society, wherein people would jump from a certain image of the state to another that was rapidly dismantling everything that was part of the prior regime. People had no time to think of democratization as a process, nor had they any idea what would be the journey of their state. They were claiming democracy while elites were in a competition of ‘who catches the first the profits of institutions available’; that is why I still refer to democracy as a myth. The role that elites have had in the prolonged transition of Albania is their impact at the same time in the state building process. The post-communist political elite which emerged as an appendix of the ancient regime exploited the regime change in the beginning of the 90s set the course of Albania’s transition. Vicious circle of transition reproducing the same discourse, the same political ‘problems’, the same modus operandi for the political parties to reach agreements and profit their ‘dividends’ of shares. According to Grzymala (2002, 537) “two institutional legacies in particular, whether society is voluntarily organized and whether a central state apparatus exists shape elite competition”. This is evident in the Albanian case where society’s power to self-mobilize for change is very weak.

To have a state building process, primarily we should understand what kind of state are we inheriting and what are we supposed to put efforts on building? In the Albanian case, the inheritance was the harsh communist legacy with personalistic dictatorship leadership style. Grzymala defines Albania as a “personalistic state-building process” (2002, 546) where people are not able to break through the system “without some level of compliance”. Thus, the process of state building is hindered by the existing ties of patronage and clientelism which were enhanced through the rapid economic transformations since the early days of the regime change and managed by the elites that had the opportunities to utilize the existing resources.

Figure2. A typology of state building processes. Following this background of analysis of post-communist countries, Albania does not make any exception in terms of how the past guide the extent of reforms, to what extent elites compete for possession of goods and resources and last, how the international ‘intervention’ is shaped during early phases of transition. Albania has adopted the most of international conventions and fulfilled international formal requirements as part of the conditionality for the sake of European Union membership and other international arrangements. Still, the ‘triple transition’ model lacks the most important element of post-communist states analysis, that of elite constraints mechanisms.

When it comes at debating on transitional mechanisms to come to terms with the past, otherwise known as transitional justice, one should not underestimate the value and the weight of political parties in the public domain. Due to the legacy of the state-party model and the penetration of Hoxha’s regime in every aspect of life of the society, political parties in Albania have strongly and persistently demonstrated unwillingness to create stability, reach broader consensus for national issues, and to build a national strategy to reconcile divided groups of the society. In other words, political parties as dominant actors and factors in Albania have utilized this domain for their personal profit through two main characteristics: under the Democratic Party rule there was a tendency to use the discourse of communists/anti-communists by highly politicizing processes especially within the judiciary branch. While under the Socialist Party rule there have always been tendencies and data on corruption and state capture. The latest trends in this matter will be analyzed in the following sections. While defining the characteristics of each state building model, the Weberian and Durkheim’s ones, it is notable the necessity to add the ‘locals’ into this process. In Albania, many reforms and grand processes/ institutional or political projects have been initiated and supported by the international community, leaving no room for local ownership. In this context, it should be built a new relationship between international-local in order to foster legitimacy and provide ground for the development of capacities. ‘The more is better’ approach is not enough for the political community to foster legitimacy or save authority, thus the democracy promotion paradigm should be advanced with the inclusiveness of public. The more is better should increase channels of communications and representation between state-society, in order to set democracy into the proper tracks. After all, democracy is all about people and their relationship with the state. In Albania there is a say that liberalization and not democratization shapes the contours of national transition. The relationship between State and society, the one of State and political parties, indicate the degree of ‘rent-seeking’ behavior which exclusively rest upon the patronage and clientelism bonds within the formal and informal networks.

Krastev (2002,50) puts it like this:

“As regards the Balkans today, there are at least three different ways to conceptualize state weakness. The strength of the state can be measured in terms of capabilities. A second measure is how its ‘consumers’ rate it and the third approach to state weakness defines the weak state as captured by particular interests that dominate policy …”Due to the changes of post-Cold War, the perception of state building was rather simplified (Robinson 2007). In brief, the concept of State has been theorized in two main approaches, taken as a guide to the state building. Secondly, world historic periods have identified different sort of States in terms of their strength and weaknesses. Thirdly, responses/ interventions to emerging States after World War I, States that emerged after the dissolution of the Former Yugoslavia, and States after the events of 1989 as post-communist countries, have been given as a static stance towards democratization and state building, without taking into consideration the contextualization of each State. This is more evident in the approach followed to the post-communist countries, not encountered for their past legacy and past power still in charge within institutional structures, economic resources and elites. The same ‘therapies’ were followed in different countries, without the local agency. Thus, the triple transition known for the post- Soviet States lacks a fundamental element, that of contextualization through people’s participation in the processes. The two preconditions that Grzymala (2002,546) set as crucial components for the democratization in the modern era are “formal institutions and organized societies that constrain elites”. Obviously, elite constraining is the Achilles heel in post-communist countries, in view of the legacy that previous regime has left as a ‘toolbox’ to retain power and control state resources. Most of the post-communist countries and societies have not fully dealt with their past, thus mechanisms that were thought to be as facilitators for societies towards democratization, were in some part absent or in other parts unfinished and with no success at all. All these elements combined define the post-communist context which is left unknown and kept regardless in designation of reforms and ‘interventions’ to state building.

Other scholars like Kopecky (2006,251) point the finger to the political parties as “representative agencies, giving voice to well-established constituencies, and deriving legitimacy from their capacity to articulate their voter’s interests and to aggregate their demands”. Apparently, through the floating space of state building analysis, various scholars focus on elites, political parties, civil society and international-local nexus. Their common denominator is legitimacy of political system, democratization in the modern era. Other factors within the whole spectrum of state building process are accountability, transparency, rule of law. Even in this regard, post-communist political parties differ from those in the Western democracies. One of the harshest characteristics of Hoxha dictatorship was the killing and disappearance of all opposition and pro-democratic elites. The lack of dissident movements is another distinguished feature of dictatorship, which facilitated the ongoing regime for forty years. No matter the years, rather than the behavior, attitude and the concept of constitutionalism that let behind. Pluralism of political parties in Albania eventually did not impact democracy, rather than created a multi-polar spectrum of narrow political interests, that in continuity contributed to a highly divided society but with no difference in party ideology or agendas. Political parties in Albania are dominant; they take the public space through intense discourse via visual and social media. Following the legacy of One Party-state, still political parties tend to keep the close connection within the state apparatus and utilize institutional structures in favor of their interests. Kopecky (2006, 253) identifies two main reasons why the political parties in Eastern Europe utilize state resources to their profits, that are: “most parties in the region originated and continue to originate even at present as elite groups within parliaments and governments rather than as social movements; secondly, the principal task of post- communist parties and elites has been to rebuild the institutions of the state” That suffices to say that the political parties and their rules have served as the “only game in town”.

What is even more ‘beneficial’ for the sake of this analysis, has to do with the nature of communist State, in terms of it was strong or weak. Literally saying, a dictatorship regime embodied in a highly controlled State with no separation of powers, might be considered as strong, in terms of having capacities and capabilities to keep under harsh control all the segments of the society and of politics. People ‘viewed’ and ‘accepted’ this kind of State as strong and as the only agency able to provide goods and services. They were submitted to this tutelage and lived within the boundaries of the myth of State and of common good. What people perceived as strong, was in fact a weak State that couldn’t provide basic goods and that human rights were denied and mass violated. After the 1989 events, people claimed to be ‘submitted’ to another form of political system, the democracy that they had never experienced before. This myth covered the political discourse and deep reforms for over thirty years. The history of State building in Albania starts in 1944, thus every unit of analysis before and after the 1989’s events reflect the lenses of State-party, surveillance, state apparatus closed to the party network, personalistic dictatorship and patronage. The transition that Albania had to transcend with the fall of communism, cannot be let aside of these precise features of the Albanian history, that is the very first format of State under the communist regime.

Linz and Stepan (1996) differentiated liberalization and democratization. Mentioned above in the case of Albania, often is misinterpreted the process of democratization by being interfered with a political narrative used during elections or weak moments of governance. Democracy has always been banged in the face of people to show them that the reforms, constitutional changes, political agreements before and after elections, even the sabotage of the parliament in 2017 by the opposition, are all considered as part of the big puzzle of democratization. In this sense, democratization process is simplified, diverged and considered mostly as a formal procedure that can be measured through fair elections and/or good governance. As Linz and Stepan (1996,4) would name as “electoralist fallacy” they would argue that precisely this basic requirement of democracy is transformed and narrated as a “sufficient condition of democracy”.

To return to Linz and Stepan discussion on the consolidation of democracy, it is worth mentioning that their three combined principles of behavior, attitude and constitutional dimension favor a narrower concept of democracy, respectively the one that goes beyond fair and free elections. This minimalist form of democratization is used by Albanian political leadership as the main discourse to shape what we should expect by democracy. Fukuyama (2004,5) as one of the leading scholars on state building, states that “the state building approach, which was at least as important as the state-reducing one, was not given nearly as much thought or emphasis” He explicitly contributes in the field by putting the emphasis on four aspects of stateness in order to “distinguish between the scope of state activities and the strength of state power”. These four parts of a package include: organizational design and management, political system design which is much related to the institutional design at the society as a whole, basis of legitimization that is the necessity to be perceived as legitimate to the society and the last is about cultural and structural factors.

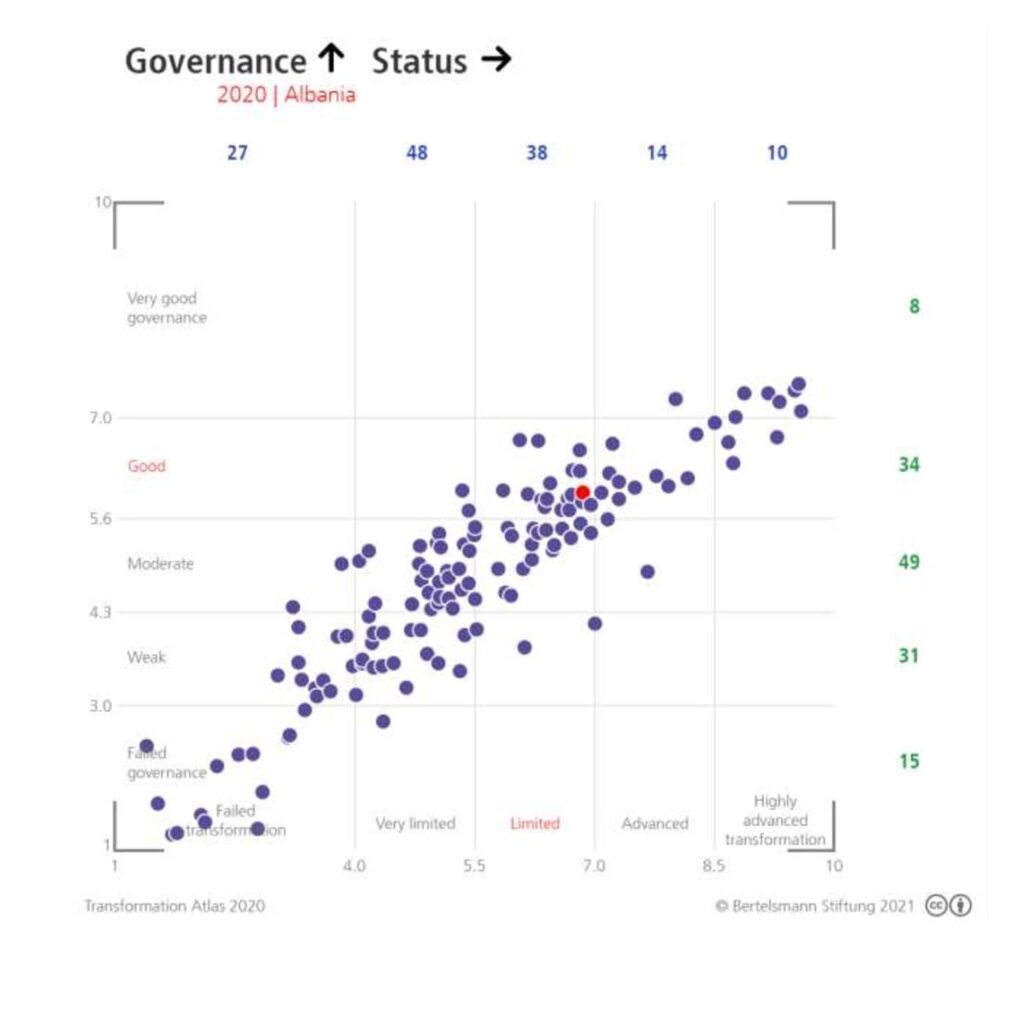

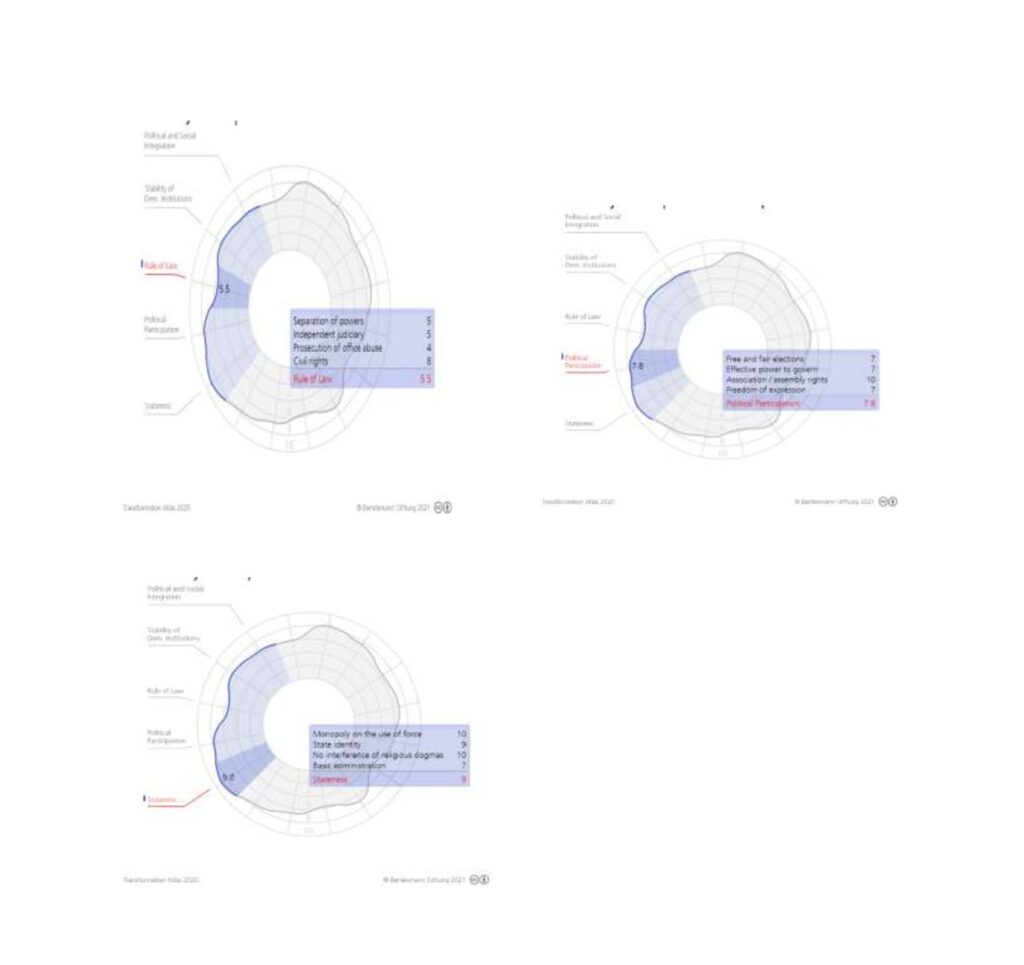

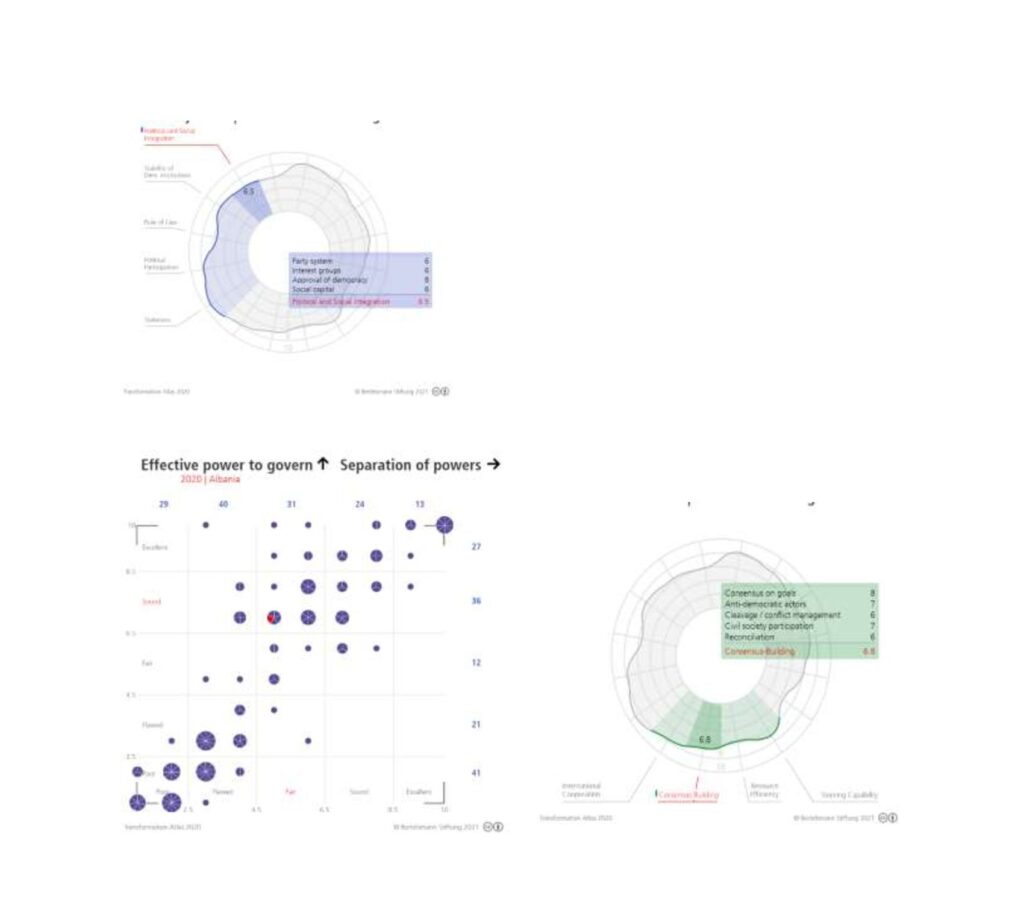

BTI Index (The Transformation Index) provides us with the data on political, economic and governance transformation. For the sake of this article, I will detach results from 2006 (there is no data prior to this year) until 2020 on the rule of law, political participation, stability of democratic institutions, stateness and consensus-building.

“Albania has shown progress in institutional reshuffling and amending its legal codes in key EU priority areas, but there is still a large gap between quick and frequent institutional changes and slow and uncertain implementation.” (BTI:2020).

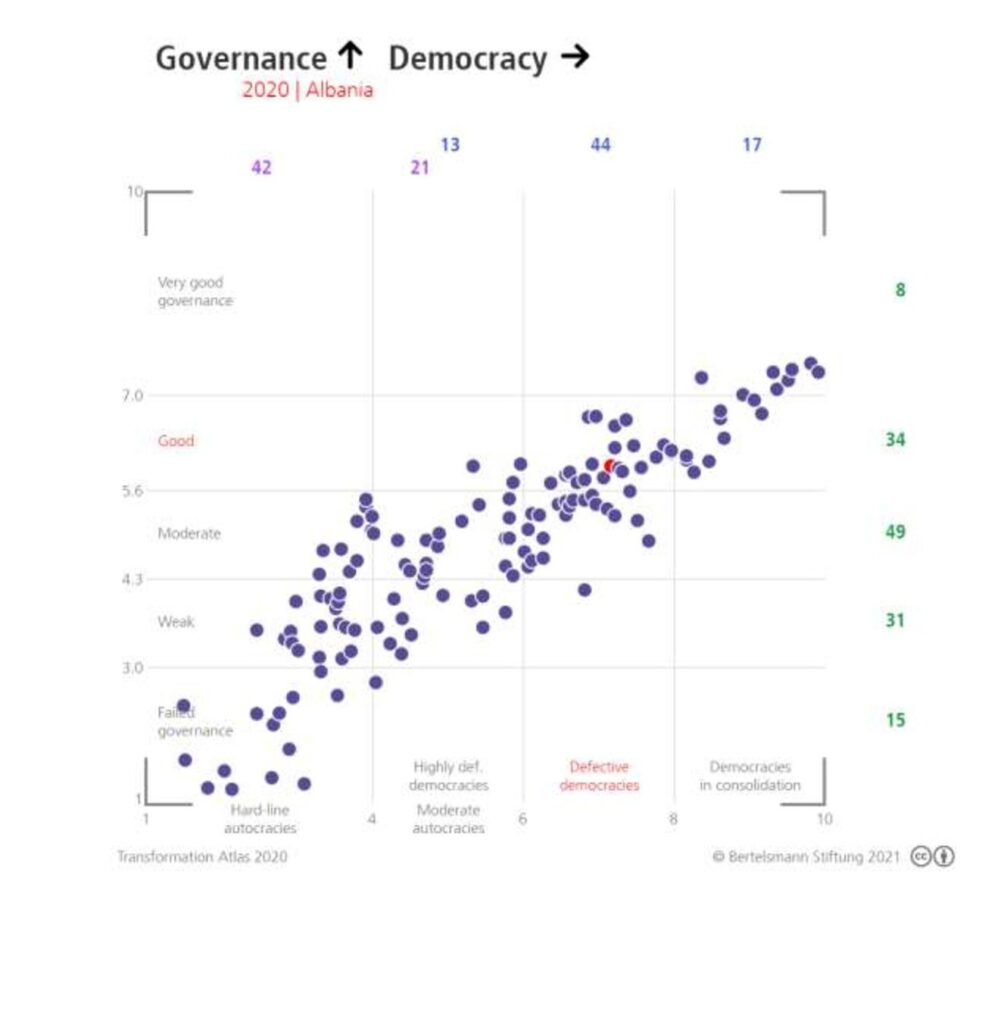

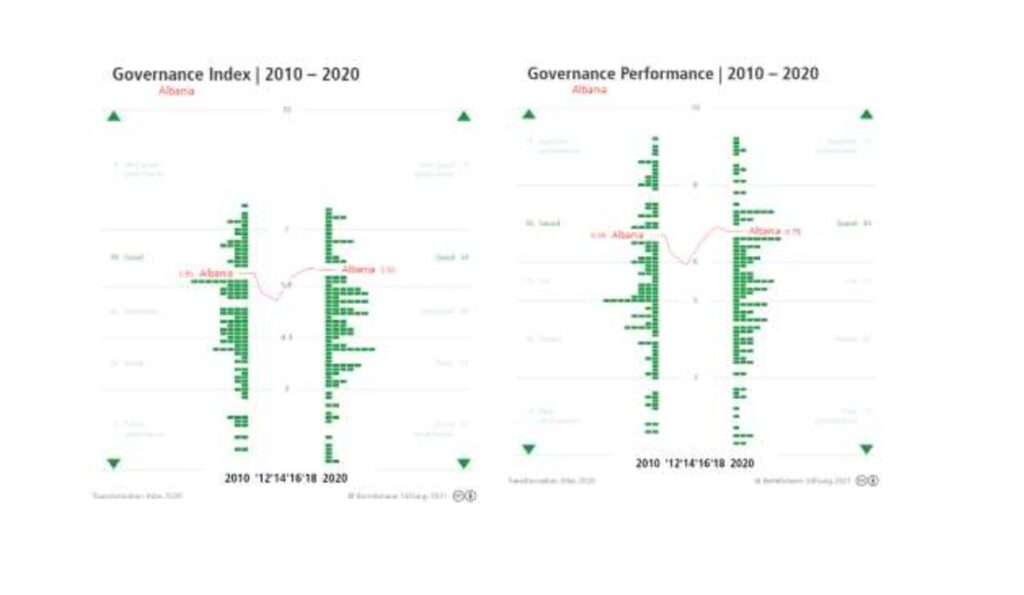

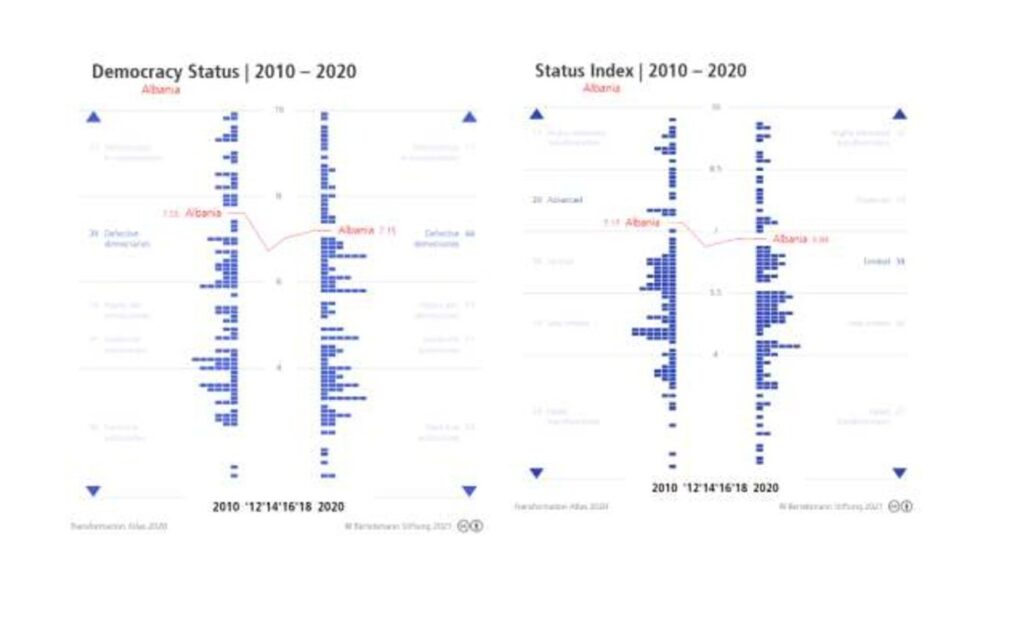

Keywords emerging from these two graphs are ‘defective’, ‘limited’ and ‘good’

In a timeframe of a decade, from 2010 to 2020, BTI Index shows that Albania’s Governance Index score has increased by 0.10 points, the same increase level as the Governance Performance Index score.

Democracy status from 2010 to 2020 has declined by 0.40 points and the Status Index score has declined by 0.33 points. Criterias such as political participation, rule of law and stability of democratic institutions have shown decrease points, while two criterias such as stateness and political and social integration have showed little change. In its annual country Report for Albania, BTI has highlighted the term “long-neglected state building reforms” as a mark to the unwillingness and inability of political leadership to advance state-building more accurately and in a more sustainable way.

Another key Index on monitoring and evaluating the democracy on global basis is the Nations in Transit through the annual reports of Freedom House. The Country report for 2020 indicates that: “National Democratic Governance rating declined from 3.50 to 3.25; Electoral Process rating declined from 4.50 to 4.25. As a result, Albania’s Democracy Score declined from 3.89 to 3.82“(Freedom House 2020). Not surprisingly, huge reforms, specifically that on the judicial branch neither transformed political behavior, nor contributed to the effectiveness and accountability of national governance. Holding a democracy score of 3.75/100, Albania is yet a transitional/hybrid regime, and a partly free country when it comes at freedom scores. Rule of Law Index estimates the overall Albanian score of 0.49, which reflects a decline of 0.01 points from 2020 and 0.03 points from 2015. In this Index, I would detach ‘Constraints on Government Powers’ scoring 0.43, reflecting a slight decline year by year. From 0.55 points in 2015 to 0.43 in 2021. As for ‘Fundamental Rights’ in Albania, there is shown a decline of 0.01 points from 2015 to 2021. What is interesting in light of ‘Order and Security’ section, civil conflict is effectively limited scores the highest point of 1.00, while people do not resort to violence to redress personal grievances scores lower than even the regional average, 0.46.

In order to understand state building in Albania, it is a must to understand the state capture approach as a one-way ticket to authoritarianism and not merely a deficient democracy. Based on the latest report on state capture published by the Transparency International “In governments where corruption and state capture are systemic, the institutional system can progressively take on certain characteristics that enable its manipulation” (2020, 25). The case of tailor-made laws is present in circumstances that “can be instrumental for the capture of law making”. The dominance in number of law-proposals from the Executive to the parliament represent one of the key characteristics of the tendency of politics to dominate the space of public domain, who is quite inexistent when it comes at proposing law amendments or law-proposals. In this regard, the State as in times of dictatorship, ‘knows’ better where and how to amend legislation. The extended legalization of politics and vice versa the politics that legalize their narrow interests of clientelism provide grounds for the “prevalence and consolidation of state capture through legal mechanisms”. That is not suffice to say that a box of paradoxes is the case of Albania, where in discourse, volatility of institutions, impunity, tendencies of authoritarianism, oligarchy concerns, go in the same direction with efforts to fight corruption, emerged institutions as a product of judicial reform, electoral reform and ongoing constitutional changes. This is not a TRANSITIONAL phase. It goes beyond efforts of a society to break with the past and build its own institutions in line with democratic system and the rule of law. This is transformed into a normal phase of politics, economic and social way of living. High rates of immigration do not show other than ‘submission’ to the system installed.

Conclusion

To conclude, international institutions that evaluate governance, rule of law, democracy, and accountability, reflect on some common issues when it comes at state building in Albania. Keywords of these insights and reports indicate low rates of transparency, lack of accountability, and no separation of powers. These measurements are parts of the whole picture of analysis when reflecting after thirty years of pluralism in Albania. It might be useful to use these Indexes and their methodology to describe what is happening in Albania, but there still lacks integrated research under topics of post-communism, regional studies and transitional justice. State building is not just a matter of institutions, because we have been witnesses of the increasing number of institutions in a decade and rates of transparency are still low. Theoretical part has its own paths of improvements in order to give more focus on contexts, national and societal characteristics. Scholars of state theories and those of state-building should converge more with each other in order to view state building not merely in the light of approving new institutions but to attach to it the impact of legitimacy and public authority. In thirty years, Albania has demonstrated that its form of state is still hostage to the past practices. The public is still far from active participation and consultation for key national issues. It is not sufficed to stop and stare to the decades of post 1989 events, but to track elements of the state in the past and drag the analysis of state building into the framework of history, narrative, network ties, community and class struggle.

References

Adiministration, Department of Public. 2020. “Department of Public Administration .” Accessed October 20, 2021. http://dap.gov.al/publikime/dokumenta-strategjik/64-strategjia-ndersektoriale-e-reformes-ne-administraten-publike-2015-2020.

Anna Grzymala-Busse, Pauline Jones Luong. 2002. “Reconceptualizing the State: Lessons from Post-Communism.” Politics & Society 30 (4): 529-554. doi:DOI: 10.1177/003232902237825.

Buzan, Barry. 1983. People, States and Fear . Wheatsheaf Books.

Chandler, David. 2007. “The state-building dilemma: good governance or democratic government?” In State Building , by Neil Robinson Aidan Hehir, 70-89. Routledge .

David Chandler, Timothy Sisk. 2013. The Routledge Handbook of International Statebuilding. New York: Routledge .

Dhembo, Elona. 2014. Albanians and the European Social Model. Study Report , Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

Durkheim, Emile. 1957. Professional Ethics and Civic Morals . Routledge .

Grimm, Sonja. 2019. “Democracy promotion and statebuilding.” In Handbook on Intervention and Statebuilding , by Nicolas Lemay-Hébert, 93-104. Edward Elgar.

House, Freedom. n.d. Freedom House . Accessed October 27, 2021. https://freedomhouse.org/.

Ilir Kalemaj, Dorian Jano. 2009. “AUTHORITARIANISM IN THE MAKING? The Role of Political Culture and Institutions in the Albanian Context.” CEU Political Science Journal 4 (2): 232-251.

Juan J. Linz, Alfred Stepan. 1996. Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation . The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Kalemaj, Ilir. 2020. “Albania: A Taxing Journey Toward Democratic Consolidation and European Integration .” In Political History of the Balkans ( 1989-2018), by József Dúró – Zoltán Egeresi, 23-35. Dialóg Campus.

Kopecký, Petr. 2006. “Political parties and the state.” Journal of Communist Studies 22 (3): 251-273. doi:DOI: 10.1080/13523270600855654.

Krastev, Ivan. 2002. “The Balkans: Democracy without Choices.” Journal of Democracy 13 (3): 39-53. doi:DOI: 10.1353/jod.2002.0046.

Lemay-Hébert, Nicolas. 2009. “Statebuilding without Nation-building?Legitimacy, State Failure and the Limits of the Institutionalist Approach .” Journal of Intervention and Statebuilding 3 (1): 21-45. doi:DOI: 10.1080/17502970802608159.

Marshall, Monty. 2010. “The measurement of Democracy and the Means of History.” Springer 48: 24-35.

Project, World Justice. n.d. World Justice Project . Accessed November 1, 2021. https://worldjusticeproject.org/.

Robinson, Neil. 2007. “State-building and International Politics.” In State Building , by Aidan Hehir & Neil Robinson, 1-28. Routledge.

Stiftung, Bertlesmann. n.d. Transformation Index. Accessed October 20, 2021. https://bti-project.org/en/reports/country-dashboard/ALB.

Uvalic, Milica. 2012. “Transition in Southeast Europe: Understanding Economic Development and Institutional Change.” In Economies in Transition. Studies in Development Economics and Policy, by Gerard Roland, 364-399. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230361836_15.

Zuniga, Nieves. 2020. Examining State Capture: Undue Influence on Law Making and the Judiciary in the Western Balkans and Turkey. Transparency International .

Ines Stasa is a PhD candidate in International Relations at University of EPOKA, Albania. Her research interests revolve around transitional justice, democratisation, statebuilding and security.