By Rudina Collaku

According to literature, there is still a general opinion that Violent Extremism (VE) and terrorism are issues that concern men only. However, as the data show, about 550 Western women have travelled to ISIL / Da’esh-occupied territory and 17% of foreign European fighters/ warriors are women (Orav, A., Shreeves, R., Rad- Jankovic. A., 2018). Moreover, according to Europol, one in four people arrested in Europe for terrorist activities in 2016 was a woman (Orav, A., Shreeves, R., Radjenovic. A., 2018). Furthermore, recent studies highlight the fact that women’s involvement in extremist organizations and their role in conflicted countries or violent situations are often more complicated than assumed (Eggert, 2018), and that women at the same time “can be victims, violent actors or agents of positive change” (Dufour-Genneson, S. Alam, M., 2014).

This paper analyzes the factors that push Albanian women towards religious radicalization

and participation in foreign conflicts.

The paper challenges the existing gap in studies which have focused on men, given that the number has been higher and hence has missed the nuances from a gender perspective. The methodology uses first-hand testimonies, interviews and focus groups as well as a literature review to address specific factors at both the micro level: psycho-sociological and ideological factors; and the macro one: socio-economic, political, and specific cultural factors. Women may act as peace-builders, including through women’s organizations, using their influence in the families and communities to establish unique solutions to support prevention, de-radicalization, psycho-sociological support, and rehabilitation from radicalization and violent extremism (Dufour-Genneson, S. Alam, M., 2014). On the other hand, women are not only the victims of VE. They can also serve as mobilizers and supporters for terrorist organizations, recruiters, fundraisers, and even as doers of terrorist acts (Bhulai, R., Peters, A., Nemr, C., 2016).

Throughout the review of the existing literature on “push and pull factors of Albanian women in violent extremism,” it was noted that, as in men, there is no one specific factor for women and girls that affects the process of radicalization and/or their participation in terrorist groups or their travelling to the conflicted areas of Syria and Iraq (Jakupi, R., Kelmendi, V., 2017).

As field researchers in Albania, we reached the same agreement as well. Based on existing literature and analysis of information obtained from several state and non-state actors, one in-depth interview with a woman returned from Syria and Iraq and their families and relatives, as well as perceptions of respondents in the national survey, the push and pull factors are divided into two levels: macro and micro. Guided by the interaction of these factors and the complexity for addressing them, women’s influencing factors in violent extremism in the Albanian context are analyzed based on two main pillars:

- Factors at the macro level comprise the political system, the good-governance, socio- economic and social elements, faith and religion, influence of social groups, violence against women, gender inequality, and marginalization. Addressing these factors requires appropriate policy direction from both central and local government institutions with particular focus also on the community’s behavior and resilience.

- Factors at the micro level include psycho-sociological and ideological factors that can be addressed through individual work and support to the families of women belonging in these categories.

Findings on macro-level factors

Based on the academic agreement so far, the category of macro factors includes three main separate groups, such as socio-economic, political, and specific cultural factors. Within each of these factors, a wide range of conditions interact: Interactions under the socio-economic factors include high levels of social marginalization, poorly governed areas, human and women’s rights violations, and unmet social and economic needs.

In contrast, interactions under the political factors include involving high levels of corruption, impunity for elites and specific cultural factors in Albania (Vurmo, Gj., Sulstarova, E., 2018) including the influence of local religious clerics, and level of religious education. These factors, combined with other factors at the personal level (micro-level), can create the right “ground” to develop individuals/groups of vulnerable people who can be easily manipulated by extremist ideology (Vurmo, Gj., Sulstarova, E., 2018).

The analysis of these factors, as well as the identification of the most specific factors for women and girls, is essential in addressing and further drafting appropriate interventions for families, communities, or other groups/ or people who may be vulnerable to this phenomenon (Holmer, G., Bauman, P., 2018).

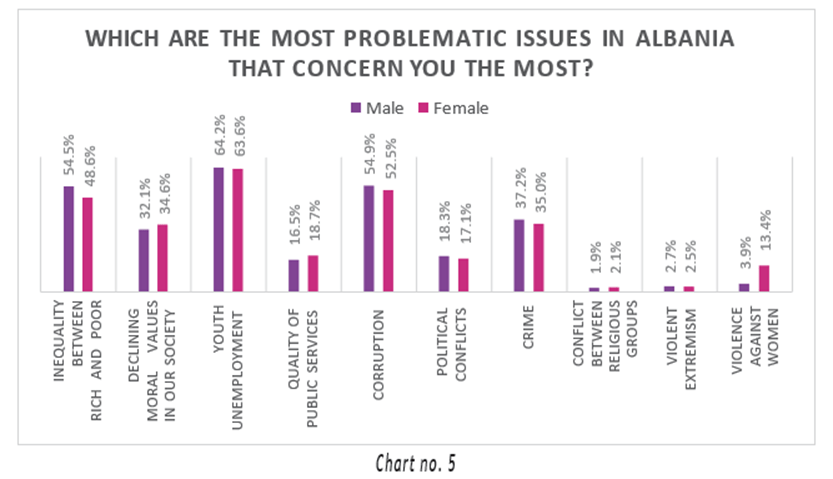

The surveyed population in this study was presented with several options, as to which are the most concerning issues for Albania (chart no.5). As noted, the three most problematic issues the respondents are most concerned about are youth unemployment, which holds the highest level at 63.9%1(64.2% of male respondents and 63.6% of female respondents), followed by high levels of corruption with 53.7% of the general surveyed population (54.9% of male respondents and 52.5% of female respondents) and the inequality between rich and poor comprising 51.5% of the general surveyed population (54.5% of male respondents and 48.6% of female respondents).

From a gender perspective, there is no difference in responses among all male and female survey respondents. Variation can be seen as regards the high level of corruption, which is mostly listed as a problematic issue among respondents in urban areas (58.7%), compared with 47.6% of the respondents in rural areas. The perception of the presence of crime in the country is high (36.1%), as is the “decline in the moral values of the society” (33.4%). The data from the survey is also a reflection of the socio- economic situation of the Albanian population, especially of the Albanian youth. According to the latest data of the INSTAT, the unemployment rate in the 15-29 age group is 21.4% (21.2% males and 21.5% females) (De Bruijn, B., Filipi, Gj., Nesturi, M., Galanxhi, E., 2015). Although these figures rank Albania in the first place among the countries of the Western Balkans for a low unemployment rate among youth, still the unemployment figures remain twice as high as those of the states of the European Union (World Bank Group, 2019). According to another study, unemployment and lack of security have also pushed many young people into leaving Albania during 2018-2019, where 40% of youth claimed that they wanted to leave the country (Kamberi, G., Çela, A., 2019).

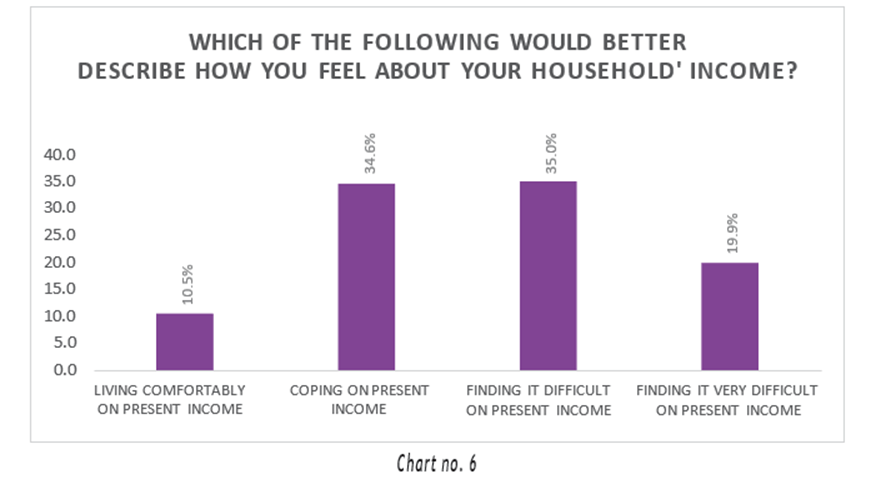

The financial situation and economic polarization play an essential role in the overall “well-being” of the population and in the context of violent extremism. As such, individuals radicalized into violent extremism over the last few years in the Western Balkans (including those who have become foreign fighters) have come mostly from the economic margins (Vlado Azinović, Kimberly Storr, 2017). Even though the financial situation cannot stand as a single factor influencing VE, when combined with other factors such as widespread corruption and lack of security and justice may be a factor exploited by VE groups, which may offer wages or services. It is not poverty however that elicits support for VE but rather the acute form of social exclusion by government and society (Vurmo, Gj., Sulstarova, E., 2018). The surveyed population states that it is difficult for them to make a living on their income. In percentage terms, the male and female respondents share more or less the same approach in terms of difficulty they have in making a living, where the highest percentage is present at the levels “coping on present income” and “difficult” as presented in chart no 6.

In fact, the difficulties in affording life are closely related to the employment rate and monthly income. Among the survey respondents, there is a high difference between women who do not have any income (31.6% of respondents) and male respondents (16.6%). There is little difference in revenue for the category of women and men who earn 23,000 Albanian Lek (ALL) (21.4% – women and 20.6% – men). Reversely, this difference increases for women and men who earn over 50,000 ALL per month; thus, there is a gender pay gap with a higher percentage of men who make over 50,000 ALL compared to women.

The survey, the focus group discussion, and the interviews noted the difficult economic situation (intertwined with other factors further discussed in this study) as one of the reasons why Albanian women (mainly from rural areas) have travelled to warring areas or the Islamic State. One example is the case of 16-year-old Besa2, who was married at the age of 14 and faced a challenging economic and social situation.3 After her husband left, her financial condition worsened. She lived in a mosque for a certain period because she alone could not afford to pay the rent of the house until she joined her husband abroad.4 However, the poor economic conditions of people who travelled to Syria or Iraq are not the only factor. There are also other cases where most FTF families have had average living standards5, owned small businesses, and were not to be considered poor since they could cover the travelling expenses by themselves6. These cases were reported from interviews with the returned woman and relatives of other returnees. One of the testimonies shows that the people who are currently in the war camps (including women) were, on their arrival to Syria/Iraq, initially treated well. Their minimum living conditions were met, and the daily budget spent on a family reached hundreds of dollars a day. 7 It is precisely this misinformation that “seduces” unemployed people, those with economic difficulties and from deep rural areas. However, other testimonies were taken by other families who still communicate with their family members who are in the Al-Hol camps. They claim that their situation is miserable, as the interviewee says: “Recently they desperately want to return, the situation is terrible and they are starving…” claiming that they are continually asking for financial help.8

On the other hand, difficult economic situations are related to the low employment rates of the population; however, it is difficult to say that unemployment is the only factor influencing Albanians to travel to Syria and Iraq. In the context of radicalization and violent extremism, unemployment constitutes an essential resource to individuals or extremist groups in radicalizing individuals (men and women) by promising a solution to their poverty and offering more lucrative economic opportunities through illegal ways.

Civil society representatives in the focus group discussions state that people, particularly those from rural areas, have been more “attractive” for the recruiters given their difficult economic situations. The high level of corruption is more evident in rural areas, combined with a lack of proper religious education too.9 Endemic corruption is part of the multi-faced set of drivers of violent extremism. Evidence from Transparency International suggests that the lowest-scoring countries on the Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) are often those experiencing conflict or war (UNDP, 2018). On the same note, the UN Secretary General’s Plan of Action on Preventing Violent Extremism suggests that countries that fail to control corruption (amongst other indicators like poverty, unemployment, and diversity management in accordance with human rights obligations) tend to witness a more significant number of incidents linked to violent extremism (UNDP, 2018). Survey respondents list corruption as one of the three problematic issues that most concern them (see graph. no.5).

The same concern among the Albanian population is visible in the opinion poll, “Trust in Governance 2019.” Most Albanian citizens perceive petty corruption (87.5%) and grand corruption (85.2%) as a widespread or very widespread phenomenon in Albanian society. Furthermore, the same opinion poll in 2019 reveals that 15% of the Albanian population has personally witnessed government corruption at the central level and 25.2% at the local level (Vrugtman L, Bino, B, 2020).

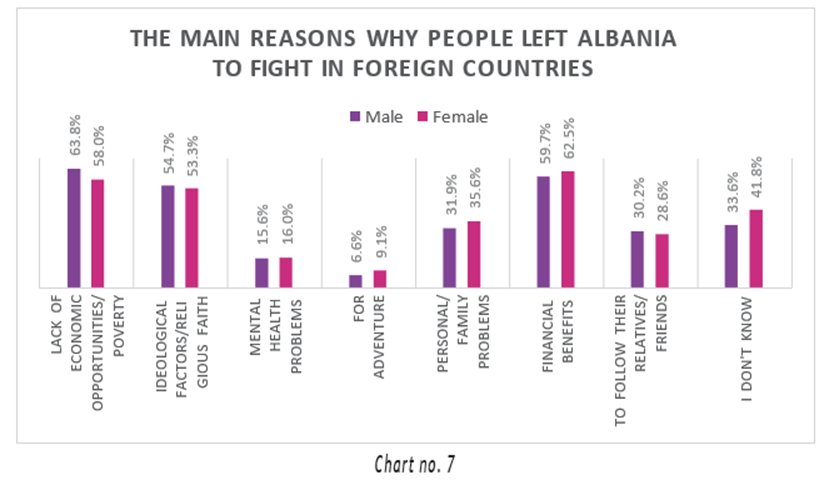

Chart no. 7 provides an overview of the perceptions of respondents on the main reasons why people (both women and men) have left Albania to join warring countries such as Syria and Iraq. What is noticeable is the high percentage of respondents who think that one of the main reasons is “financial benefits” (62.5% female respondents and 59.7% male respondents). This percentage is followed by a “lack of economic opportunities” (58.0% of female respondents and 63.8% of male respondents) and then “for ideological and religious faith” (53.3% of female respondents and 54.7% of male respondents).

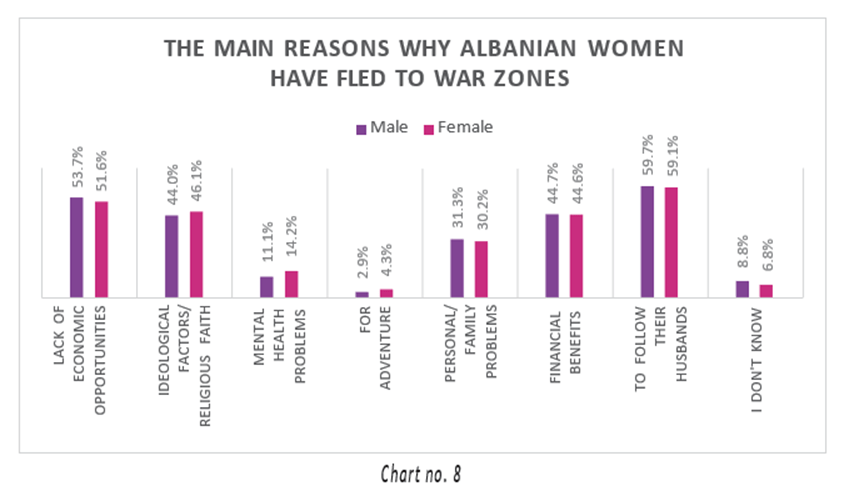

In the meantime, based on the perceptions from the general survey’s population, the factors that lead women in Albania to travel to warring countries of Syria and Iraq are reported as follows (Chart no.8). The highest percentage stands for “to join the husband” from both male and female respondents (59.1% female respondents and 59.7% male respondents). Also, other reasons are highly considered by the respondents, such as “lack of economic opportunities” (51.6% female respondents and 53.7% male respondents) and “financial benefits” (44.6% female respondents and 44.7% male respondents).

The dominance of these factors, particularly of the fact that the Albanian women have flown to war zones to join their husbands, is also underlined by civil society representatives engaged in preventing violent extremism in Albania, who from their experience (albeit based on little information they possess given their limited engagement at concretely working with returnees, women and their families) show that most Albanian women have not played an active role in the Islamic state.10 Still, they have travelled there to have a better life and to escape from extreme poverty. Many of them think that in these warring countries, they will find the house they did not have and the rights they believe they have been denied regarding lack of job opportunities and lack of equal earnings (Ramkaj, 2019). Also, they believe they will be able to provide a good living for their children, as is the case of the woman named Moza,11 who followed her husband due to the lack of income in raising their three children. 12

The information from experts on VE in Albania shows that “Albanian girls and women, once in Syria, have been isolated at home, under constant pressure from other women with foreign citizenship. There were many non-Albanian women engaged in the fighting areas. Their contacts with the family were rare due to field engagement. The children did not receive normal education but only manipulative instructions in selected centres from the organizations they had joined” (Gjinishi, 2020).

Although women constitute the main priorities of some policies in Albania (INSTAT, 2020), the context given above shows once again that women’s economic empowerment, labor market engagement, labor force participation, and unpaid work in the family, particularly in rural/ remote areas, as well as the position of youth and especially girls in the labor market, continues to remain a challenge in the Albanian society. This is also highlighted in the “Gender Equality Index Report for Albania” (2020). The interaction and amelioration of these factors, under the perspective of violent extremism, are essential for building women’s resilience and increasing their role in peace-building and prevention of VE (Coutur, 2014).

Gender Inequality and Patriarchy as a Cultural Factor

The principles of gender equality and non-discrimination are fundamental principles of the International Law on Human Rights. Promoting gender equality is a priority of all Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) member states, which have taken the commitment to promote gender equality as an integral part of their policy (OSCE, 2000). Although the literature so far suggests that women are led into VE by the same group of socio-economic and political factors, other existing literature sheds light on specific factors that influence women’s engagement in VE, such as gender inequality, gender-based discrimination, and lack of economic and educational opportunities (Orav, A., Shreeves, R., Radjenovic. A., 2018).

Apart from the traditional factors leading to the VE, the analysis and the strong link between gender inequality and violent extremism have been addressed by Valerie Hudson and her co-authors in “Sex and World Peace.” They state that the best predictor of peace in a nation is not its level of democracy or wealth but rather the level of physical security enjoyed by its women (Hudson, Valerie M., 2012). Historically, women have been included in the category of marginalized groups in terms of access to the labor market, low opportunities for education, and low levels of participation in decision-making. The experience of living in a society that denies women’s full civil rights and economic opportunities can make some women perceive involvement in terrorism as a way to gain freedom, emancipation, respect, and equality (Orav, A., Shreeves, R., Radjenovic. A., 2018). Violation of these rights can deepen feelings of alienation, isolation, and exclusion that may make individuals more sensitive to radicalism (Orav, A., Shreeves, R., Radjenovic. A., 2018).

In the Albanian context, the General Gender-Equality Index for 2017 marked 60.4 points, demonstrating a significant gender gap of 7 points below the EU-28 average (67.4), except for the area of governance, where Albania has a higher level of gender equality than other European Union countries. The most significant shortcomings in the gender gap in Albania are encountered in the fields of knowledge, money, and time spent doing unpaid labor (INSTAT, 2020).

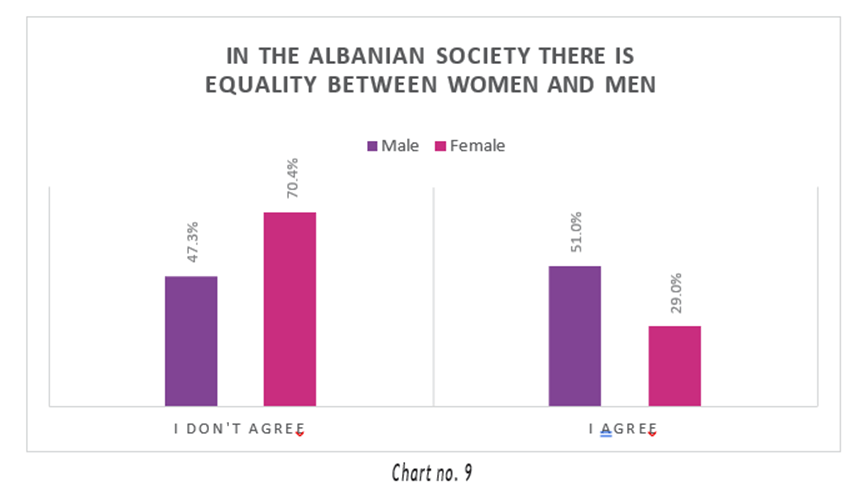

Gender inequality is noted to be at high levels even among respondents of this study, where 47.3% of men and 70.4% of women claim that there is noticeable inequality between men and women in Albanian society (chart no 9).

Higher levels of gender inequality, especially in terms of education, are more visible in rural areas of the country. In these areas, the number of men with secondary or higher education is higher than the number of women with secondary or higher education which is due to fewer possibilities for proper education, low rates of attendance at high school, and lower enrollment rates in vocational schools. Quality assessments (Housing and Population Census, and PISA study) raise concerns about the deterioration of the education system in rural areas. Some of the causes of this difficult situation are insufficient investments in infrastructure and human resources, high distance from residential areas, and vocational training institutions. Also, very few women participate in training programs, due to insufficient time and how training programs are organized (Zhllima, E., Merkaj, E., Tahsini, I., Imami, D., Çela, E., 2016).

From a geographical point of view, there is no specific cause or group of reasons that affect women differently in different parts of the Balkans and European countries. However, some of the instigators and tendencies of radicalism and women’s participation in terrorist/radical organizations are exposed differently in the Balkans, compared to other European countries such as Germany, France, and the United Kingdom (Kelmendi, 2018).

This is due to the more significant challenges faced by women in the Balkans in terms of domestic violence, high levels of discrimination in socio-economic issues, and the dominance of patriarchal societies (Kelmendi, 2018). In the Albanian context, it is still challenging to address domestic violence, protect victims of domestic violence, guarantee gender equality and gender equity, and provide minimum health and social services, especially at the local level (EC Albanian 2019 report, 2019). For example, in the first two months of 2020 in Albania, five women were assassinated by their husbands. (Tushi, 2020). According to data provided by INSTAT and the survey on violence against women and girls in 2018 (INSTAT, 2019), it turns out that 1 in 2 women (52.9%) between the ages of 18-74 have experienced one or more than five kinds of violence (intimate partner violence, violent encounters, non-partner violence, sexual harassment and/or intimidation) during their lifetime (INSTAT, 2019).

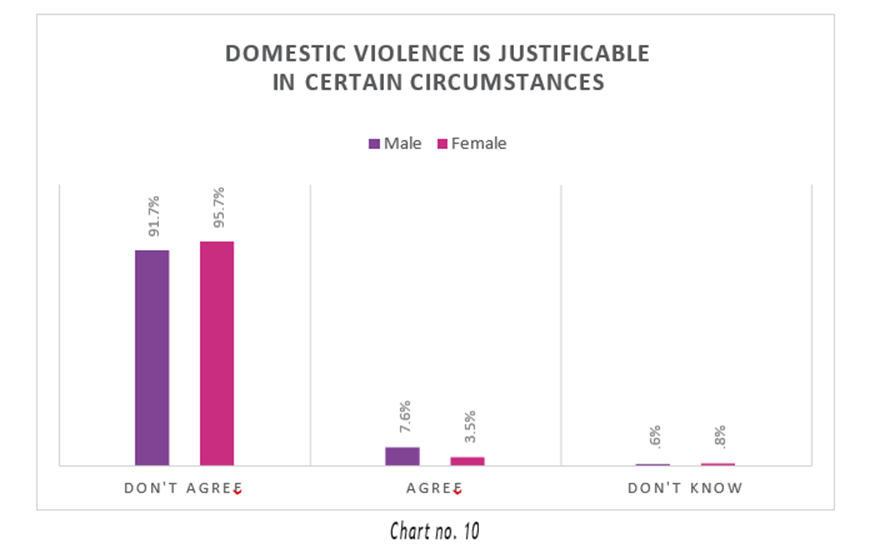

Moreover, according to the same study, traditional patriarchal attitudes remain prevalent throughout Albania thus contributing to gender inequalities in all spheres of social and economic life, as well as the prevalence of violence against women.13 We also notice the “legitimacy” of violence against women among the respondents in the study, as shown from chart no.10, where 7.6% of men and 3.5% of women agree with the fact that violence against women is justifiable in certain circumstances.

Patriarchal norms, the dominance of the male figure in the Albanian family, and “power” over women are noted by participants in the target group discussions to be among the most significant factors as to why Albanian women have travelled to war areas in Syria 14 and Iraq. From the data of this study, there is only one case identified of a woman being raped by her husband and forced to accompany him to Syria. In contrast, most of the interviews taken from relatives of women and men still in war zones do not support the hypothesis that these women have been forced to follow their husbands. Instead, they have voluntarily (for a better life)15 joined their husbands to be near them (even when asked to do otherwise), and this shows once again the deep roots of patriarchal norms within the Albanian family, mainly in rural areas16 based on the “family code” (Kuko, 2020).

However, even in one case where the mother refused to join her son who had already left for war, the decision of the head of the family (father) was dominant, forcing his wife and his two other daughters and son to go to war. This example clearly shows that the man’s role as the head of the family enforces the patriarchal factor of society. 17

The “patriarchal” factor is also supported by the interviewees and participants in the discussion meetings from different areas of Albania. According to them, “Albanian women have travelled to warring zones because they did not want to oppose their husbands. Whether ideologically convinced or not, the women obeyed their husbands. Still, they did not travel there to fight”. 18 Such statements confirm the patriarchal context that prevails in the family structure in Albania. This context is also present and rich in evidence from women who returned to other Balkan countries where patriarchal norms (especially those within the Muslim community) have played a significant role in their participation in conflicted areas in Syria and Iraq (Kelmendi, 2018).

In this patriarchal context, the majority of Albanian women who have travelled to the Islamic State have also “legitimized” the reasons why their husbands left “to earn money and provide the family with a better income for a better life.” The statement “A husband’s primary task is to be the breadwinner” is also supported at high levels by 48.2% of men and 45.7% of women surveyed.19 Given the social and economic differentiation between men and women and the “duties” that women exercise in a patriarchal context, most women remained without any financial or family support after their husbands fled to the war zones. Some of these women were supported by their parents; while others were to remain with their husband’s families, with their in-laws, and some women were left without any support at all. In this situation, the only solution for them was to join their husbands wherever they were. 20 This situation is criticized by various civil society actors in the country who emphasize the need to focus on the role of women and girls, especially in rural areas. The CSO representatives suggest that more efforts should be made to educate the younger generation on gender equality to break gender stereotypes.

Furthermore, they deem it important to boost economic empowerment and vocational education for women and girls. “Such interventions will help prevent cases such that of the girl from a low-income family, who was married at the age of 14 and at the age of 16 she left for Syria with her child to join her husband, who died there. The misfortune of this girl seems never to end as she was forced to remarry and give birth to another child” 21.

Another case of a woman who testified that she did not want to stay there shows that she simply joined her husband after he had assured her that they could have a better life in Syria because the situation would soon get normal.22

Factor Analysis at the Micro-Level

The individual factors and nuclear family

The analysis of the micro-level factors influencing the decision of Albanian women to join the Islamic State is based mainly on the testimonies of relatives of women who have gone to Syria and Iraq. Also, it is based on the testimony of the returned woman and other evidence gained from civil society representatives and state institutions in Albania. Analysis at the micro-level is vital to understand factors that involve, as described by Dr. Alex P. Schmid: identity problems, failed integration, feelings of alienation, marginalization, discrimination, relative deprivation, humiliation (direct or by proxy), stigmatization, and rejection, often combined with moral outrage and feelings of (vicarious) revenge (Schmid, 2013).

In this category of micro factors, we find out that Albanian women are driven by individual motives, mainly related to the perspective/structure of their marriage, which is again closely associated with patriarchal norms. Almost all the evidence in this study sees the women as “victims” of their husbands and their aggravated financial situation. They are unable to raise and educate their children on their own. Some of them were even lied to by their husbands over the real situation in Syria, as the woman returnee Mira (not her real name) testifies: “My husband left 3-4 months before us. He asked me to go there, telling me that the situation was normal. I didn’t tell anyone I was leaving; even the kids didn’t know. They thought they were flying to England.” 23 The same testimony comes from relatives of another case who emphasize that “the woman didn’t even have a say in her husband’s decision to leave for Syria, but simply went after him. She respected his decision because that is how it should be.” 24

In this analysis of the personal motives that led Albanian women to fly to war countries, a crucial role is played by the close family (parents, in-laws, sisters, and brothers) and the interaction of family members. From the information obtained from the interviews with the relatives and acquaintances of people who fled to Syria and Iraq, almost none of the parents, sisters, or brothers were aware of the fact that the sons of the family at first and their wives were planning to leave to join the Islamic State. This is the case of a woman named Mira, whose family supposed that she went with her children to England to join her husband. It was her brother who, on occasion, noticed that her sister was not in England, one day when she wrongly had left the computer’s location on. Testimonials show that the moment when the parents have understood where their children are has been shocking. The case of woman returnee Mira can be considered a positive one, given the fact that her family managed to bring her and her two children back. However, this is not the case for other parents looking for help from the state institutions to turn back home their children.

Despite being unaware of this phenomenon, the traditional and patriarchal form of the family organization is still visible. In such families, the men of the family are supposed to be the ones who should take care not only of their wives and children but also, in some cases, even increasing the responsibility and pressure of young men to take care of their parents as well. With this mindset, men who have left for war countries have easily been able to lie to their families by making them believe that they are immigrating to Western European countries, such as England, Greece, and Germany, or to study in the Middle East. The control of radicalization as a process and the role of the nuclear family in preventing this phenomenon are issues that have also recently begun to come to the attention of actors dealing with violent extremism. However, so far in Albania, there is no evidence of cases of families that prevent the travelling of their children to Syria/Iraq.

From our observations for this study, people (men and women) come from families with traditional backgrounds of the Albanian family, respecting and considering the role of the husband as a pillar of the family. In contrast, the respondents in the study emphasize that the structure of the Albanian family has changed since the ‘90s. It faces more issues that affect its “sustainability” due to the socio-economic problems, especially in rural areas, the perceived reduction of moral values in society by young people, and the complete lack of care for their old parents (Ramkaj, 2019). The decrease in moral values in the community is also listed as one of the issues that concern the most 32.1% of male respondents and 24.6% of female respondents in the survey of the presented study (see graph no.5 above).

________________________________________________________________________________________________________

1 This is the average value

2 Not her real name.

3 Participants in this focus group discussion included representatives from the municipality of Pogradec, teachers, high school students, representatives of healthcare institutions, journalists, and religious community representatives (Pogradec, January 19, 2020).

4 Interview with the grandmother of the man foreign fighter W, (January 16, 2020).

5 Interview with the friend of a woman Mira, (January 5, 2020).

6 Interview with the sister and daughter of the family of fighter Y, (November 8, 2019).

7 Interview with the sister and the daughter of the dead fighter, (November 8, 2019).

8 Interview with the sister-in-law of the foreign fighter Z, (November 1, 2019).

9 Participants in this focus group include local actors in Vlora municipality such as: high school representatives, teachers, students, CSOs, representatives from shelters, youth groups, members of the Security Council. (Vlora, January 24, 2020).

10 Focus group “PVE Forum” discussion meeting, Tirana, (February 20, 2020),

11 Not her real name

12 Testimony of Y woman mother-in-law who died in Syria, (January 12, 2019).

13 Participants in this focus group included local actors in Tirana municipality such as teachers, social workers, psychologists, lawyers, and members of the National Forum of CSOs in PVE in Albania. (Tirana, February 20, 2020).

14 Participants in this focus group included local actors in Tirana municipality such as teachers, social workers, psychologists, lawyers, and members of the National Forum of CSOs in PVE in Albania. (Tirana, February 20, 2020) Ibid.

15 Interview with the friend of the returned woman X. (January 5, 2020).

16 Ibid.

17 Interview with the sister of the Y fighter who is currently in Syria and at the same time the daughter of the family (who is there to stay close to the Y fighter), (November 8, 2019).

18 Participants in this focus group include local actors in Vlora municipality such as high school representatives, teachers, students, CSOs, representatives from shelters, youth groups, and members of the Security Council. (Vlora, January 24, 2020).

19 Nationwide survey for this study, WCDCA, 2020.

20 Testimonies from relatives of women who are currently in camps in Syria and Iraq.

21 Participants in this focus group discussion include representants from the municipality of Pogradec, teachers, high school students, representatives of healthcare institutions, journalists, and religious community representatives, (Pogradec, January 19, 2020)

22 Interview with woman returnee Mira, (October 28, 2020).

23 Interview with woman returnee Mira. This is not her real name, (October 28, 2020).

24 Testimony of members of the family of the returned woman Mira, (December 1, 2019).