An approach from Lea Ypi’s

Free. Coming of Age at the End of History

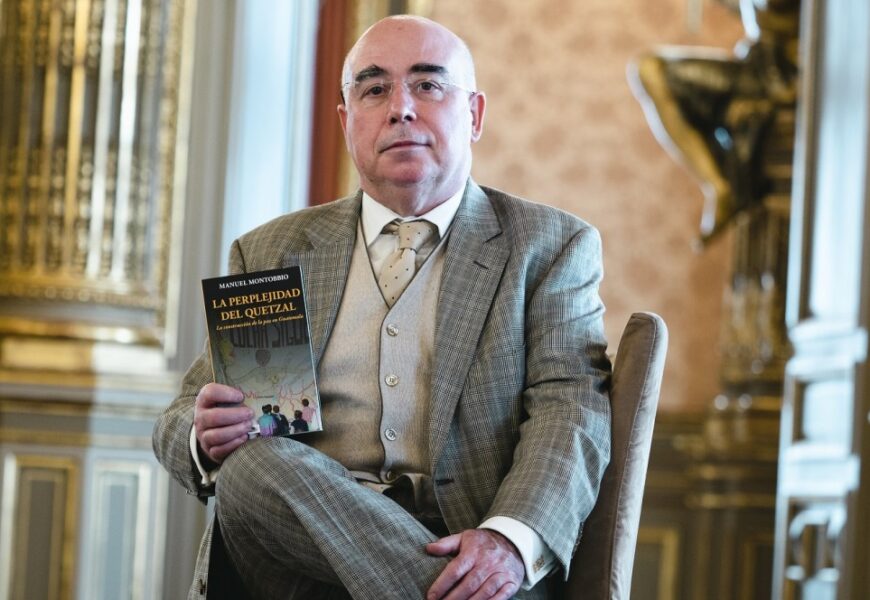

Manuel Montobbio

Ideas are written and formulated with words, theories and concepts; and they are written and formulated with life and in life. With the reason, and with the soul. Freedom does need of both scriptures; since it has no meaning if it is not for life and by life. Perhaps this is why, during the confined time of the COVID-19 pandemic, Lea Ypi, Professor of Political Theory at the London School of Economics, decided to write an essay on the idea of freedom in the socialist and liberal traditions, ended up by writing the story of her life.

Of the presence in it of freedom in her progressive awareness in Enver Hoxha’s Albania and her experience of the communist regime created by him and its fall and transformation to democracy and the market Economy under the “shock therapy” that ends up leading to the collapse of the State in the crisis of the financial pyramids in 1997, and the stabilizing foreign military intervention of Operation Alba, a moment that coincides with her completion of high school and departure to Italy to pursue her University studies.

Experience of the collective epic of the Albania of Enver Hoxha’s regime and that of its fall and pendulum transition towards the free market, a limit case of the embodiment in History of the idea of freedom in the tradition of really existing socialism and in the liberal tradition and their respective legitimizing discourses, ideas-force and words-talisman; be them the class struggle, the dictatorship of the proletariat, collectivization and the planned economy, anti-imperialism and the leadership of the Party; be them the magic hand of the market, structural reforms, transparency and human rights, the International Community and civil society.

Ideas whose application involves tragedies, such as the imprisonment of relatives – presented to the girl Lea as their absence due to her studies in “universities” which were actually prisons -, or the great escape and collective exodus after the fall of communism, or the collapse and evaporation of family economies in the faith in the multiplying capacity of the money of the financial pyramids.

This lived History of Albania undoubtedly offers us material for reflection on freedom, and with it on power and its meaning in both systems; and Lea Ypi offers it to us in her book through the protagonists of her personal story – from her family and outside it, from their actions and their words – and the ideas and experiences that they embody and transmit, from their activities. Like, in her most immediate environment, the conception of freedom of her mother, Noli, as the absence of prohibition to do what one wants, and the confidence that the exercise of that freedom will lead to the better functioning and satisfaction of society.

Or his father, Zafo, who considers it contrary to freedom to be told what to do, whether in the coercion of communism, or in the ineluctable need for the structural reforms that are wanted to be imposed when he is the administrator of the port of Dürres after its fall, that imply the dismissal of the majority of its workers, as if they were numbers and not people; and something in his conscience tells him that freedom is not only that of thought and consciousness, but also that of the conditions that society provides us to realize our agency and potentiality as persons, in line with what Amartya Sen tells us in Development and freedom. Or that of her grandmother, Nini, who, after her childhood and early youth as the daughter of a Pasha in Ottoman Thessaloniki, settles for love in Albania, where she will experience so much adversity and lose everything, except her dignity, in that conception of freedom as an affirmation of the self, of the person we are and want to be above and beyond the circumstances and vicissitudes that we have to live through.

Or as – as a theorizing counterpoint to each system – Nora, the teacher who teaches them about communism at school; or the Crocodile, the World Bank official nicknamed after the one he always wears on his shirt, an expert in country transitions towards market economies and Western homologation and in promoting the reforms they entail. Professor Ypi tells us in the epilogue that freedom is not sacrificed only when others tell us what to say, where to go or how to behave; that a society that claims to allow its members to realize their potential, but fails to change the structures that prevent them from flourishing, is also oppressive; and that, despite all the limitations, we never lose our inner freedom, that of doing what we consider fair and appropriate.

Lea Ypi intended to write, reflect and make us reflect on freedom and the ideas and theories about it in the socialist and liberal traditions, and undoubtedly, she succeeds in a way that a theorizing essay on them could have not. Since the first freedom is, somehow, that of reflecting on freedom itself, and at the same time accepting the freedom of the other to do so too, to seek it and always exercise and build it.

To understand and assume that all these conceptions have their meaning and necessity. To understand, especially and above all, as she tells us at the end, that freedom is a desire always to be realized, that her world, our world, is as far from freedom as that which her parents – our parents, we could say in Spain and so many other latitudes – tried to leave behind; but that, without understanding the failures and challenges they faced, we will remain divided and unreconciled, and will hardly be able to make of ours time to fight for and accomplish freedom.

She intended that, and that she has achieved; but not only: also – and I would say so fundamentally – to give voice to the voice of Albania, that it tells us, through her story, the epic of its contemporary History, invites us to live it in first person, and meanwhile show us the ability to ask and wonder about what happens and what happens to us, somehow breaking a silence, banishing amnesia and oblivion, calling other voices, perhaps through other first images which may open the floodgate from which the story may flow, and the ink on the blank paper.

As in her case, “I never asked myself about the meaning of freedom until the day I hugged Stalin” that day in December 1990 when the eleven-year-old girl she was then hugged the legs of Stalin’s statue in search of refuge, and when she looked up, she discovered with surprise that Stalin’s head was not on his shoulders, torn off by those who were protesting outside shouting for freedom and democracy. That emptiness on the shoulders and that outcry triggers her writing. In my case, it evokes the image of the first Ambassador of Spain in Tirana who I was, and who, close to finalizing his posting, at the end of two thousand ten managed to visit the warehouse where were kept the statues of Stalin and other icons of communism, on which pigeons and oblivion perched. Oblivion of the time when Lea Ypi hugged it.

Oblivion of the time when the statue of Enver Hoxha was demolished at Skanderbeg Square and the other statues were taken to the warehouse of oblivion. In my case, it evokes that image, as well as that of the Colonel Engineer who emerges alive from the bombing of the bunker that Enver Hoxha had commissioned him to build, and then he was ordered to bunkerize all of Albania, as Kujtim Casku so well depicts in his film Colonel Bunker. Since it is through the construction of the bunkers that populate Albania on the outside and those that imprison our souls on the inside and their subsequent deconstruction, that I have undertaken in my book Búnkeres – a dialogue with the poem of the same title, part of my Guía poética del Albania (Poetical Guide of Albania) – the reflection on power, freedom and soul inspired by the collective epic of Albania’s contemporary History, from the experience of having lived alongside the Albanians a part of their journey.

To liberate oneself is to debunkerize oneself: for this we need of prose and Philosophy; but also of Poetry, that which tells us that to deconstruct the bunkers we turn our eyes and look inside our soul, we ask ourselves who we are, who we want to be, which book we want to write with our life in the world and in life, and that invites us to learn to look with the heart and to write poems with life.

_________________________

Manuel Montobbio, diplomat, writer and Doctor in Political Science, was the first resident Ambassador of Spain in Albania (July 2006-January 2011) and is the author of Guía poética de Albania (Albanian edition Udhërrëfuesi poetic i Shqipërisë, Tirana, Botimet Poeteka, 2012), Búnkeres and other publications on Albania and the Western Balkans, as well as on European construction on peace processes, international and intercultural relations, political transitions and compared politics. His book Salir del Callejón del Gato. La deconstrucción de Oriente y Occidente y la gobernanza global is published in Albanian by the Albanian Institute of International Studies as Te dalësh nga rrugica e maces. Dekonstrusioni I Lindjes dhe I Perëndemit dhe qeverijsa globale. An approach to his academic and literary work can be found at his webpage www.manuelmontobbio.net