by Altin Gjeta

Introduction

Albania’s transition from communist dictatorship to democracy has been marked by high political polarization. The political discourse has been characterised by harsh rhetoric and soon emerged two opposing antagonist camps. Democracy is inherently plagued by division and competition of conflicting interests. Antagonism and polarization have been seen as the unavoidable predicament of a democratic polity; indeed as a challenge to be actively assumed and not as a symptom of a political pathology to be eliminated”.1 In the same vein, Larry Diamond contends that democracy is, by its nature, a system of institutionalized competition for power, but any society that sanctions political conflict runs the risk of becoming too intense, producing a society so conflict-ridden that civil peace and political stability are jeopardized.2

Political polarization has been one of main features of most post-communist countries in Central and Eastern Europe.3 However, what distinguishes Albania from other countries is the fact that polarization has not taken place along ideological or programmatic lines, rather it seems to have its roots in the communist past, is elite driven and anti-political. Sharp political polarization results where different social groups create and operate categories and mechanisms where members of different groups and social groups are fiercely loyal to their “own group”, want to win at all costs, and dehumanize, depersonalize and stereotype other group members. All of this emotional hatred produces pervasive psychology of polarization, where it causes or deepens fear and insecurity.4 Political opponent is constantly casted as an enemy to be destroyed, dehumanized and depersonalized. The recent report of the Institute for Political Studies notes that the parliamentary debate in Albania is dominated by harsh rhetoric, derogatory language and personal offences between political opponents.5

Unlike other Eastern European countries, the boycotts of parliament and violent protests have been a unique feature of Albania’s transition towards democracy. In 2019 the opposition relinquished its seats from the parliament and boycotted the local elections. This was ensued by large opposition-led demonstrations in the streets of Tirana. The radicalization of political life has created cleavages that cut across the whole social life of the people. In absence of other alternatives, people are forced to side either with the Socialist Party or the Democratic Party, the two main political parties in Albania. Whether or not people support a particular side, in a highly polarized society, they are forced to choose a side or be labelled by others as belonging to a side or group.6

The division of the people into two hostile poles has foreclosed the democratic life of Albania and protracted its post-communist transition towards a functioning democracy. Therefore, it is normatively and theoretically relevant to investigate and analyse the origins of political polarization in Albania. In the first section of the paper I discuss shortly the theoretical tenets of political polarization and then move to the second part where I analyse the root causes of the political polarization in Albania, namely the traumatic experience of the communist past, the role of the political elite in polarization and the emergence of the politics of anti-politics as a driver of political polarization.

Political Polarization in short

Polarization occurs when a normal multiplicity of interests and identities in a society begins to group along a single dimension, splitting into two opposing camps.7 Whereas political polarization is normally defined as an ideological distance between political parties – political elite or voters

in society and their positions or attitudes toward each other.8 Thus, difference, the dichotomy us/them becomes the identifying feature of a polarized society. Polarized democracies reveal that members are fiercely loyal to their group sides, want it to win at all costs and that mechanisms of dehumanization, depersonalization, and stereotyping work as a whole to the other group party.9 The formation of two poles along a single dimension is especially sharpened in the persistence of high-level political tensions. Polarization, in which identities and interests clash in tension, “simplifies rather than complicates the structures of division” unlike other types of identity-based mobilization and “mutually aligns divisions that cut diagonally across a single rift”.10

Polarization manifests itself in a series of lines such as populism-anti-populism, religious-secular, national-cosmopolitan, traditional-modern, urban-rural, austerity-anti-austerity, market- statist economy.11 These cleavages are more than often exploited by political actors, namely political parties or leaders to reinforce more division, gather support and rule the population.

In this process, polarizing rhetoric and political tactics become instrumental. Polarization that

emerges in this context suppresses “in-group” differences and combines multiple and intergroup

differences into one difference or even one that becomes negatively charged and is used to define the other.12

The other is casted as alien to us, and in a polarized society people define politics and society through the distinction between “we” and “they”. This makes consensus, interaction and tolerance around policy issues highly unlikely and costly for the political actors. For instance, a wide range of political and national security issues begin to come to the centre of meaningless and bitter debates, and a political climate that constantly generates risks emerges.13

McCoy and Somer have made a significant contribution to the literature on political polarization by identifying the most common features of political polarization, which can enable a general framework for political polarization to be drawn as follows: The division of the people into two hostile poles, where multiple divisions are aligned around a single dominant division or demarcation line between the two camps; the transformation of the political demands and interests around these identities; both sides’ moral characterization of the division as “good” and “bad” ignoring the possibility of common interests between different groups; greater cohesion within groups and the possibility and reality of greater conflict and hostility between groups; stereotyping and prejudice towards the out-group due to lack of direct communication and/or social interaction; disintegration of the centre and polarized camps trying to label all individuals and groups in society as “we” or “other”; weakening the middle ground in public and political discourses; the hostile relationship manifests itself as an element of distinction in the spatial and psychological worlds-situations of polarized groups.14

In a polarized society each camp questions the moral and legal legitimacy of the others and sees the opposing camp and its policies as an existential threat to their way of life or the nation as a whole.15 The “other” is not perceived as a political opponent to compete with but as an enemy or criminal that must be defeated and destroyed altogether. In this regard, peaceful coexistence is no longer perceived as possible by citizens.16 Such strong feelings of dislike and distrust towards opposition parties, candidates, and social groups make this extreme polarization particularly dangerous.17 People standing in the middle ground are constantly pressured to side with one group or the other, making societal consensus impossible to be achieved. Instead of referring to others as ‘you’, people begin referring to the out-group as ‘them’. This change in language reflects and reinforces the politics of alienation and exclusion at the social level.18

The communist past divides the present

Albania experienced one of the most Stalinist communist regimes in Central and Eastern Europe where the majority of its citizens were subject to state’s surveillance and draconian punishment practices. The communist regime had built a particularly repressive security apparatus, which oppressed all forms of dissidence, expropriated individuals, interned and sentenced to life or to death tens of thousands of people that disagreed with its policies. Under the Communist leadership of Enver Hoxha, Albania was described as one of the most repressive regimes in Central and Eastern Europe, and “one of the most tightly closed societies in the world”.19

Its policy towards social and cultural customs was the harshest of all, and it was the only regime in the world that banned religious practices altogether.20 The unprecedented scope and severity of the communist repression against human rights would make one argue that Albania had strong reasons to make a clear brake with its communist past and mature democratically.

In fact Albania undertook some transitional justice measures in the beginning of the 1990s, such as amnesty, public administration purges, lustration and criminal trails. Nevertheless, as I have argued elsewhere, these measures were ill-framed and politicised – thereby they lacked cross party consensus and their implementation was significantly hindered by the communist political legacy.21 As a result, Albania fell short of regime’s victims and wider public aspirations to seriously and sincerely address communist regime’s human rights violation.22 The inability of Albania to implement transitional justice measures has amplified political and social polarization towards its totalitarian past. A survey conducted by the OSCE Presence in Tirana on citizens’ understanding and perceptions of the communist past in Albania and expectations for the future revealed that 62% of the respondents did not see the communist past as a problem. However the most controversial figure was that when asked about the role of the former dictator Enver Hoxha in the history of the country, more than half of the respondents had a positive perception.23 This was explained mainly by Albanian’s society not being sufficiently informed about the dictatorship and by the lack of de-communisation.24

However, the survey shows that society is divided about the past. The failure Albania to deal with its totalitarian past has perverted the uncovering of the past state’s human rights abuses, thereby undermining the establishment of a shared understanding and memory of its totalitarian past. Public education in every post-conflict or post-authoritarian rule is important in order “to reduce the number of lies that can be circulated unchallenged in the public discourse”.25

According to a study more than 60% of the school teachers were not aware about the number of victims of the communist regime because the country’s criminal past is not reflected into the school curricula.26 In the absence of an official history regarding the communist regime’s abuses, particularly the youth has rested upon confusing and conflicting information coming mainly from family members, media and communist period films produced by Kinostudio e Re (the communist state-owned film production agency) which was part and parcel of its propaganda. This has created a confusing and conflicting assemblage of communist historical account among the youth, which in turn has neither helped the acknowledgment of victims’ sufferings, nor reconstruction of a shared understanding about the communist regime’s wrongs.

Albania’s inability to expose the abuses of its totalitarian regime and establish justice has thus led to the downplaying and denial of the communist dictatorship’s human rights abuses. This has nurtured a distorted historical narrative in the public sphere, which keeps portraying communist Albania in schoolbooks as a progressive state that provided electrification, free health care and education as well as universal suffrage (the right to vote only for the ruling party) – overshadowing the crimes, economic and social misery it brought about to the country. Keeping this narrative alive has made it impossible to build a unifying collective memory over the communist past in Albania.27 Failing transitional justice has thereby hardened political and social cleavages. As Etkind maintain, if we fail to achieve justice for those wronged, to fully understand the nature of what happened – if we fail to mourn for the collective suffering of the nation, we enter into a post-catastrophe period. In the post-catastrophic world, “the past haunts the citizenry, divides the society and limits political choice”.28

Three decades after the fall of the communist regime, Albania continues living a post-catastrophe period. The communist rule has left behind painful memories of oppression, stigmatization, humiliation and a culture of deep distrust, extreme friend-foe thinking and a violence mentality.29 The debate about the past human rights abuses is divisive, hijacked and instrumentalised by both main political parties to their ends. The Socialist Party, the successor of the Labour Party has not broken away from its own past. To the contrary, it has maintained a strong link to the past by promoting the historical narrative of the communist regime and packing its leadership with former communists. While, on the other hand, the Democratic Party has utilised the communist past to attack its political opponent, and gather support around itself from the former political prisoners and those who suffered under the communist dictatorship.

In addition to that, failing transitional justice in Albania has produced consequences on the social realm as well. As it is already known, thousands of people were interned, persecuted, sentenced to life in prison or kept under tight surveillance. After the demise of the communist

regime, people were able to discover who reported on them to the secret police. In a small country where ‘everyone knows everyone’, the peculiar and particularly brutal repression

methods and failed transitional justice, injustice and suffering have left behind countless unresolved personal and family conflicts.30

This has added more to the social polarization in Albania where societal relations are hunted by the communist past human rights abuses and its distorted historical account. This assemblage of failures in dealing with the communist regime’s crimes and building a shared truth and memory has inflicted tensions in the society, thus dividing Albanians in communists and anti-communists. This has left no room for moderation and foreclosed the democratic life of the country.

The politics of anti-politics Historical accountability sets off transition’s dynamics, is transformative and plays a forward-looking role in a country’s liberalisation process. No viable democracy can afford to accept amnesia, forgetfulness and the loss of memory. An authentic democratic community cannot be built on the denial of past crimes, abuses, and atrocities.31 It is assumed that holding individuals accountable for crimes committed under the previous regime lays the foundation for a democracy committed to the rule of law and prevents future abuses under the new political system.

The failure of Albania to bring to justice the wrongdoers of the communist regime has nurtured old elite continuation. This has constantly plunged the country into a political crisis and undermined citizens’ political choices. As a result, Albania was turned into a fertile ground for political polarization and the emergence of anti-politics.

The political discourse in post-communist Albania is not framed around politics, by which

democratic politics theorist Chantal Mouffe understands the wide range of practices, discourses

and institutions which aim to establish a peaceful co-existence of different conceptions over what

constitutes a good or moral life.32 To the contrary, the unsettled historical account of the communist past is misused to construct a divisive political narrative for electoral benefits, creating two antagonist camps, the anti-communists and the successor of the communists. This has not served the needs of citizens and democracy building but rather has hardened political polarization. As Mouffe suggests if a political unit cannot transform antagonism into agonism it risks tearing apart the very social fabric of the society and dismantling democracy in the first place.33

Moreover, by emphasising the threat of ‘Communism’ versus ‘Berishizëm’, the unpolitical discourse deemphasised other internal social divisions and subsumed political alternatives, what has in turn perverted democratic representation and political choice. In April 2021 Albania held its 10th general elections since the fall of the communist dictatorship. However, most of electoral campaigns did not address peoples’ concerns and needs, but instead they were dominated by anti-politics which merely intend degrading political opponent. Political articulation of different social strata’s problems is substituted by an empty narrative which portrays the opponent as the biggest evil who should be destroyed. For instance, in 2009 parliamentary elections the then Socialist Party leader Edi Rama declared that he is not a politician at all and denounced his opponent, the then Prime Minister Sali Berisha, as a symbol of the backwardness. Nevertheless, Rama’s party did not deliver any political manifesto where farmers, labourers, teachers or other social groups’ concerns were addressed – rather he declared a total war against the ‘old politics’ without offering any alternative.

On the other hand the Democratic Party has played the anticommunism card during the 90s and continues to use and reuse it for electoral benefits without genuinely addressing social groups’ needs. This has brought to the surface a deep crisis of representation in Albania, expressed in increasing public’s distrust towards political parties and public institutions in general.34 These failures, coupled with the economic stagnation of Albania during these years and slow progress in the EU integration path have nurtured popular disillusionment towards democratic system. As post-communist Albania struggled to make progress and deliver tangible results for its population, the letter started feeling nostalgic for the communist past.

This mass dissatisfaction has been politically harnessed by communist era politicians and ancient regime’s successors to cling to power and thus protract Albania’s path towards a functioning democracy. The 2022 Freedom House report defines Albanian as a partly free country and a hybrid democracy35, while in the same vein Transparency International ranks Albania as a highly corrupt country.36 Instead of debating about policies, tackling corruption and facilitating economic growth, the political elite have operated through a binary conception of the political, where the opponent is not seen as legitimate but as an enemy. This Schmitt’s friend-enemy conception of the political has been pervasive in the political discourse in post-communist Albania. According to Kajisu, the anti-politics discourse should be seen as the outcome of two interrelated factors: the sedimentation of identities in the new post-communist horizon and the failure of political parties to articulate their positive identity.37 The two biggest political parties did shy away from programmatic articulation. Instead, they have been throwing anti-political accusations against each other. This has deepened the crisis of representation and has hardened political and social polarization in Albania.

Elite-driven polarization

There has been much debate among scholars about the role of elites in political and social polarization. According to Zingher and Flynn polarization on the elite level can dramatically affect

electoral behaviour even if it is not associated with any type of dramatic change of the electorate’s basic underlying ideological or policy orientations.38 In the same vein, Mullinix contend that elite partisan polarization alters the influence of partisanship in preference formation in the mass public in at least two ways. First, when elites are divided along party lines, they provide clearer signals about the parties’ positions on a given issue to the mass public. Second, elite polarization that emphasizes conflict between competing sides increases the salience of partisan identities.39

The political elite in Albania has inflicted tension at the political and societal level by emphasizing division as a tool to cling to power. Two main opposing camps emerged after the fall of the communist regime, the Socialist Party on the left and the Democratic Party on the right political spectrum. Both parties worked behind the scene to ensure that their monopoly over the political system is upheld. They have changed the electoral law and the constitution several times to make sure that a two-party system is maintained in the country. During the last 25 years, the two major parties have changed the electoral system before every general election in order to guarantee their political dominance.40

This has further entrenched division in Albania. The high degree of political bipolarization has successfully divided the Albanian political discourse and electorate into two antagonistic camps.41 Both sides have worked to divide the public opinion, media and civil society through the enverist [Enver Hoxha] philosophy of “he who is not with me is my enemy”.42

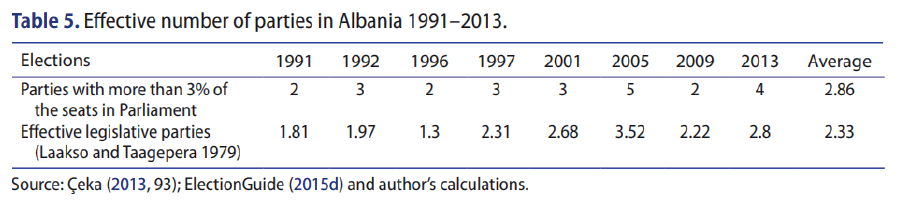

Though after the fall of the communist dictatorship more than one hundred political parties

were founded, the political scene has been dominated by two biggest parties. A quick glance at

the effective number of legislative parties in Albania during the last 22 years shows that the political scene has been dominated by an average of 2.33 parties for this period.43

TABLE 5.

By 1991, the Albanian society was deeply divided into two antagonistic camps. On the one hand was the anti-communist bloc, primarily amidst the urban, youth and better-educated population that was highly critical of the communist regime and called for deep and rapid political and economic transformations. On the other hand, there were the supporters of the communist regime, primarily amidst the rural and lesser educated part of population that called for gradual transformations and held a less critical view of the communist past.44 The political elite used these historical differences between the left and the right to craft a harsh and divisive rhetoric where the political opponent is casted as the enemy of the people. The more the two parties have converged, ideologically and policy wise, the more they have tended to polarize the political scene by portraying their political opponent as a threat to ‘the people’.45 In this regard, the voters’ behaviour was not defined by programmatic differences, but by the empty rhetoric of political leaders. Political parties in post-communist Albania were dominated by strong leaders who presided over the party structures. This gave them almost absolute power in the party which was utilised to further tight the grip on the party and delegitimise the political opponent.

Most of electoral campaigns were marked by derogatory language against opponents. This has come up as a result of the concentration of power in the hands of party leaders who seek to dehumanise and humiliatetheir political opponent, instead of delivering a political manifesto to the electorate.46 According to some experts this is a result of the communist legacy where the political opponent is framed as an enemy that must be destroyed. The lack of democratic culture is also blamed on for the failure of Albania to appeal to moderation.47 The authoritarian-style leadership has thus divided the society. The divisive rhetoric has intended to rally the mass public behind certain leaders. This has been the hallmark of Albania’s post-communist protracted transition towards democracy.

Conclusion

Political polarization seems to have been deeply embedded into the political and social life of post-communist Albania. It has manifested itself through heated divisive political discourse about the communist past, empty and non-programmatic rhetoric between party leaders. This has established two antagonist camps that have nurtured division in order to cling to power. Political polarization in Albania has its roots in the communist dictatorship legacy, is anti-political and elite driven. Particularly the failure of Albania to deal with the communist regime’s massive human rights abuses has exposed the country to communist-era-like policy making and its historical account where the past is portrayed as progressive.

Political elite seems to be more a continuation of the old communist nomenclature and the communist dictatorship’s crimes are not punished. This has undermined the establishment of a shared collective memory about the communist past which has divided Albanians into communists and anti-communists. This has been instrumentalized by the post-communist political elite for electoral benefits. Thus, societal relations and political choice are hunted by the communist past human rights abuses and its distorted historical account.

Apart from that, political polarization in Albania has not emanated from programmatic differences. Both political sides have not articulated political manifestos, rather they have appealed to the people on populist grounds. The anti-political discourse has dominated the parliamentary and the political debate. Instead of debating about policies, the political elite has operated through a binary conception of the political, where the opponent is not seen as legitimate but as an enemy that must be defeated and humiliated. This Schmittian conception of the political where the opponent is seen as the enemy hasn’t left room for moderation and consensus. To the contrary, it has entrenched both political life and social relations. The political elite has added more to this division by maintaining a Westminster-like party system,

where two biggest parties dominate the political life.

The constitution and electoral law has been changed several times to ensure that biggest parties reap the benefits of the system. Political bipolarization and authoritarian-style party leaders have fuelled more societal polarization by de-emphasizing social strata needs. Rather than debating about policies, harsh rhetoric, derogatory language and building of clientelistic networks has been the modus operandi of the political elite. This has inflicted tension and generated artificial political crises, which has divided more the people into two antagonist camps, socialists and democrats.

____________________________________________________________________________

1 Stavrakakis, Y. (2018). Paradoxes of Polarization: Democracy’s Inherent Division and the (Anti-) Populist Challenge. American Behavioral Scientist, 62(1), 43-58.

2 Diamond, L. (1990), ‘Three Paradoxes of Democracy’, Journal of Democracy, 1(3): 48-60

3 20 vjet demokraci në Shqipëri, DW, 20 mars 2012, https://www.dw.com/sq/20-vjet-demokracin%C3%ABshqip%C3%ABri/a-15817781

4 Green, D., Palmquist, B., & Schickler, E. (2002). Partisan Hearts and Minds: Political Parties and the Social Identities of Voters. New Haven: Yale University Press.

5 Kuvendi dhe deputetët: Roli kushtetues, bilanci dhe Kodi i Sjelljes, Instituti i Studimeve Politike, Tirane. https://isp.com.al/kuvendi-dhe-deputetet-roli-kushtetues-bilanci-dhe-kodi-i-sjelljes/

6 McCoy, J., Rahman, T., & Somer, M. (2018). Polarization and the Global Crisis of Democracy: Common Patterns, Dynamics, and Pernicious Consequences for Democratic Polities. American Behavioral Scientist, 62(1), 16-42

7 MaCoy, J. and Rahman, T. (2016). Polarized Democracies in Comparative Perspective: Toward a Conceptual Framework.

8 McCoy, J., Rahman, T., & Somer, M. (2018). Polarization and the Global Crisis of Democracy.

9 Fatih, E. (2022). Historical origins of political polarization in Turkey. Collective memory.

10 LeBas, A. (2006). Polarization as Craft: Party Formation and State Violence in Zimbabwe. Comparative Politics, 38(4), 419-438.

11 McCoy, J. L., & Rahman, T. (2016). Polarized Democracies in Comparative Perspective: Toward a Conceptual Framework.

12 Fatih, E. (2022). Historical origins of political polarization in Turkey. Collective memory.

13 Dixit, A. K., & Weibull, J. W. (2007). Political Polarization. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United

14 McCoy, J., & Somer, M. (2019). Toward a Theory of Pernicious Polarization and How It Harms Democracies: Comparative Evidence and Possible Remedies. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences, 681(1), 1-69.

15 García-Guadilla, M. P., & Ma, A. (2019). Polarization, Participatory Democracy, and Democratic Erosion in Venezuela’s Twenty-First Century Socialism. ANNALS, AAPSS, 681(1), 62-77.

16 Lozada, M. (2014). Us or Them? Social Representations and Imaginaries of the Other in Venezuela. Papers on Social Representations, 23(21), 1-16.

17 McCoy, J., Rahman, T., & Somer, M. (2018). Polarization and the Global Crisis of Democracy: Common Patterns, Dynamics, and Pernicious Consequences for Democratic Polities. American Behavioral Scientist, 62(1), 16-42

18 MacCoy, J. and Rahman, T. (2016). Polarized Democracies in Comparative Perspective: Toward a Conceptual Framework, International Political Science Association conference, Poland, July 23-28, 2016.

19 Kritz, N. (1995). Transitional Justice: How Emerging Democracies Reckon with Former Regimes. Washington DC: United States Institute of Peace Press.

20 Pandelejmoni, E. (2019). Kujtesa dhe rrëfimi i historive jetësore mbi kampet e punës së detyruar, internimet dhe burgjet në Shqipërinë Komuniste, Tek, TË MOHUAR NGA REGJIMI. Përmbledhje e kumtesave dhe referateve të mbajtura në Konferencën organizuar nga Autoriteti për Informimin mbi Dokumentet e ish Sigurimit të Shtetit, Tiranë, 338-35.

21 Gjeta, A. (2020). Transition without justice in post-communist Albania: Its implications to collective memory building and democracy promotion, Compilation of Paper, OSCE Presence in Albania.

22 Ibid

23 Citizens understanding and perceptions of the Communist past in Albania and expectations for the future, OSCE Presence in Albania, 2016. https://www.osce.org/presence-in-albania/286821

24 Godole, J. (2019). The young generation’s borrowed memory of the communist period, in: Godole, J. and Idrizi, I.(eds). Between Apathy and Nostalgia: Public and private recollections of communist in contemporary Albania. Tirana: IDMC.

25 Ignatieff, M. (1998). The warrior’s honour: Ethnic war and the modern conscience. New York: Metropolitan Books.

26 Godole, J. (2020). Mësuesit mungesë informacioni për periudhën e komunizmit, Godole: Duhet ndërhyrje urgjente. ABC News, 14 February. Available from https://abcnews.al/mesuesit mungese-informacioni-per-periudhen-e-komunizmit-godole-duhet-nderhyrje-urgjente/

27 Gjeta, A. (2021). Albania Remains Hostage to its Communist Past, Balkan Insight, 21 May 2021. https://balkaninsight. com/2021/05/21/albania-remains-hostage-to-its-communist-past/

28 Etkind, J. (2013). Stories of the Undead in the Land of the Unburied. Palo Alto: Stanford University Press.

29 Idrizi,I. (2021). Debates About the Communist Past as Personal Feuds: The Long Shadow of the Hoxha Regime in Albania, Cultures of History Forum, published: 27.04.2021

30 Ibid

31 Tismaneanu, V. (2008). Democracy and Memory: Romania Confronts Its Communist Past. ANNALS, 617, 166-180.

32 Mouffe, Ch. (2006).The paradox of democracy, Verso: London.

33 Mouffe, Ch. (2006).The paradox of democracy, Verso: London.

34 Kajsiu, B. (2010). Down with Politics! The Crisis of Representation in Post-Communist Albania. East European Politics and Societies, 24 (2), 229-253.

35 Freedom House report, Albania, 2022. https://freedomhouse.org/country/albania/freedomworld/2022

36 Transparency International report, Albania 2023.https://www.transparency.org/en/countries/albania

37 Kajsiu, B. (2010). Down with politics.

38 Joshua N. Zingher and Michael E. Flynn, (2015). From on High: The Effect of Elite Polarization on Mass Attitudes and Behaviors, 1972–2012. British Journal of Political Science, Available on CJO 2015 doi:10.1017/S0007123415000514

39 Mullinix, K. (2016). Partisanship and Preference Formation: Competing Motivations, Elite Polarization, and Issue Importance.

40 Çeka, B. (2013). Tezë Doktorature: Marrdhënia Mes Sistemeve Zgjedhore, Sistemit Partiak dhe Sjelljes Zgjedhore në Shqipëri. Universiteti i Tiranës, Fakulteti i Shkencave Sociale, Departamenti i Shkencave Politike. Accessed September 10, 2015 http://www.doktoratura.unitir.edu.al/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/ Doktorature-Blendi-Ceka-Fakulteti-i-Shkencave-Sociale-

Departamenti-i-Shkencave-Politike.pdf

41 Kajsiu, B. (2016). Polarization without radicalization: political radicalism in Albania in a comparative perspective, Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 24:2, 280-299.

42 Ibid

43 Kajisiu, B. (2016). Polarization without radicalization: political radicalism in Albania in a comparative perspective, Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 24:2, 280-299.

44 Vickers, M. 1999. The Albanians: A Modern History. London: I.B. Tauris

45 Kajsiu, B. (2010). Down with politics.

46 Arapi, L. (2013). E pakompromis, e personalizuar – Retorika politike në fushatën 2013, DW, 14 qershor 2013, https://www.dw.com/sq/e-pakompromis-e-personalizuar-retorika-politiken%C3%AB-fushat%C3%ABn-2013/a-

47 Ibid

References

Arapi, L. (2013). E pakompromis, e personalizuar – Retorika politike në fushatën 2013, DW,

14 qershor 2013, https://www.dw.com/sq/e-pakompromis-e-personalizuar-retorika-politike-

n%C3%AB-fushat%C3%ABn-2013/aÇeka,

B. (2013). Tezë Doktorature: Marrdhënia Mes Sistemeve Zgjedhore, Sistemit Partiak

dhe Sjelljes Zgjedhore në Shqipëri. Universiteti i Tiranës, Fakulteti i Shkencave Sociale,

Departamenti i Shkencave Politike. http://www.doktoratura.unitir.edu.al/wp-content/uploads/

2013/08/

Citizens understanding and perceptions of the Communist past in Albania and expectations for

the future, OSCE Presence in Albania, 2016. https://www.osce.org/presence-in-albania/286821

Diamond, L. (1990), ‘Three Paradoxes of Democracy’, Journal of Democracy, 1(3): 48-60

Dixit, A. K., & Weibull, J. W. (2007). Political Polarization. Proceedings of the National Academy

of Sciences of the United States of America, 104(18), 7351-7356.

Etkind, J. (2013). Stories of the Undead in the Land of the Unburied. Palo Alto: Stanford University

Press.

Fatih, E. (2022). Historical origins of political polarization in Turkey. Collective memory.

Freedom House report, Albania, 2022. https://freedomhouse.org/country/albania/freedom-

world/2022

García-Guadilla, M. P., & Ma, A. (2019). Polarization, Participatory Democracy, and Democratic

Erosion in Venezuela’s Twenty-First Century Socialism. ANNALS, AAPSS, 681(1), 62-77.

Gjeta, A. (2020). Transition without justice in post-communist Albania: Its implications to collective

memory building and democracy promotion, Compilation of Paper, OSCE Presence

in Albania.

Gjeta, A. (2021). Albania Remains Hostage to its Communist Past, Balkan Insight, 21 May 2021.

https://balkaninsight.com/2021/05/21/albania-remains-hostage-to-its-communist-past/

Godole, J. (2019). The young generation’s borrowed memory of the communist period, in: Godole,

J. and Idrizi, I.(eds). Between Apathy and Nostalgia: Public and private recollections of communist

in contemporary Albania. Tirana: IDMC.

Godole, J. (2020). Mësuesit mungesë informacioni për periudhën e komunizmit, Godole: Duhet

ndërhyrje urgjente. ABC News, 14 February. Available from https://abcnews.al/mesuesit-mungese-

informacioni-per-periudhen-e-komunizmit-godole-duhet-nderhyrje-urgjente/

Green, D., Palmquist, B., & Schickler, E. (2002). Partisan Hearts and Minds: Political Parties and

the Social Identities of Voters. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Idrizi,I. (2021). Debates About the Communist Past as Personal Feuds: The Long Shadow of the

Hoxha Regime in Albania, Cultures of History Forum.

Ignatieff, M. (1998). The warrior’s honour: Ethnic war and the modern conscience. New York: Metropolitan

Books.

Joshua N. Zingher and Michael E. Flynn, (2015). From on High: The Effect of Elite Polarization

on Mass Attitudes and Behaviors, 1972–2012. British Journal of Political Science.

Kajsiu, B. (2010). Down with Politics! The Crisis of Representation in Post-Communist Albania.

East European Politics and Societies, 24 (2), 229-253.

Kajsiu, B. (2016). Polarization without radicalization: political radicalism in Albania in a comparative

perspective, Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 24:2, 280-299.

Kritz, N. (1995). Transitional Justice: How Emerging Democracies Reckon with Former Regimes.

Washington DC: United States Institute of Peace Press.

Kuvendi dhe deputetët: Roli kushtetues, bilanci dhe Kodi i Sjelljes, Instituti i Studimeve Politike,

Tirane. https://isp.com.al/kuvendi-dhe-deputetet-roli-kushtetues-bilanci-dhe-kodi-i-sjelljes/

LeBas, A. (2006). Polarization as Craft: Party Formation and State Violence in Zimbabwe. Comparative

Politics, 38(4), 419-438.

Lozada, M. (2014). Us or Them? Social Representations and Imaginaries of the Other in Venezuela.

Papers on Social Representations, 23(21), 1-16.

MacCoy, J. and Rahman, T. (2016). Polarized Democracies in Comparative Perspective: Toward a

Conceptual Framework, International Political Science Association conference, Poland, July

23-28, 2016.

McCoy, J., & Somer, M. (2019). Toward a Theory of Pernicious Polarization and How It Harms

Democracies: Comparative Evidence and Possible Remedies.. Annals of the American Academy

of Political and Social Sciences, 681(1), 1-69

McCoy, J., Rahman, T., & Somer, M. (2018). Polarization and the Global Crisis of Democracy:

Common Patterns, Dynamics, and Pernicious Consequences for Democratic Polities. American

Behavioral Scientist, 62(1), 16-42

Mouffe, Ch. (2006).The paradox of democracy, Verso: London.

Mullinix, K. (2016). Partisanship and Preference Formation: Competing Motivations, Elite Polarization,

and Issue Importance.

Pandelejmoni, E. (2019). Kujtesa dhe rrëfimi i historive jetësore mbi kampet e punës së detyruar,

internimet dhe burgjet në Shqipërinë Komuniste, Tek, TË MOHUAR NGA REGJIMI. Përmbledhje

e kumtesave dhe referateve të mbajtura në Konferencën organizuar nga Autoriteti për

Informimin mbi Dokumentet e ish Sigurimit të Shtetit, Tiranë, 338-35.

Stavrakakis, Y. (2018). Paradoxes of Polarization: Democracy’s Inherent Division and the (Anti-)

Populist Challenge. American Behavioral Scientist, 62(1), 43-58.

Tismaneanu, V. (2008). Democracy and Memory: Romania Confronts Its Communist Past. ANNALS,

617, 166-180.

Transparency International report, Albania 2023. https://www.transparency.org/en/countries/

albania

Vickers, M. 1999. The Albanians: A Modern History. London: I.B. Tauris

20 vjet demokraci në Shqipëri, DW, 20 mars 2012, https://www.dw.com/sq/20-vjet-demokracin%

C3%AB-shqip%C3%ABri/a-15817781