Assoc. Prof. Mirela Bogdani[1]&Prof. John Loughlin[2]

Abstract

This paper examines the multifaceted and complex phenomenon of globalization, structured into six distinct sections. The introduction elucidates the concept of globalization, defining it as a complex network of interconnectedness, interaction, and interdependence among individuals, societies, and economies. The subsequent section traces the historical development of globalization through its various ‘waves’, arguing that while globalization has existed since antiquity in the form of international trade, it gained momentum through the voyages of discovery, colonialism and imperialism. However, it was not until the late 20th century that globalization accelerated on an unprecedented scale.The paper identifies two key drivers behind the increased rate of contemporary globalization: technological advancements in transportation and, more significantly, in communication and information. The invention of the internet, followed by the rise of 21st-century social media and digital networking, has propelled globalization to new heights. The thirdpartanalyses the types of globalization, categorising it into four distinct ones: economic, political, cultural, and social, addressing their respective characteristics and manifestations.The following section explores the implications of globalization, emphasizing its profound and far-reaching consequences. While globalization has yielded significant economic, cultural and social benefits, it has also generated considerable challenges and inequalities. The fifth part examines the phases of globalization, delineating four key periods: pre-World War I, post-World War II, the late 20th century, and the era of hyper-globalization. Each phase is analysed in terms of its defining features and impact on global dynamics. The final section engages with scholarly debates surrounding the concepts of ‘slowbalization’ and‘ deglobalization’,about certain developments such as the 2007–2008 Financial Crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic, which disrupted global interconnectedness and raised questions about the future trajectory of globalization. The paper concludes that, despite growing discussions on its slowdown or potential reversal, globalization remains an enduring reality that has brought substantial benefits to humanity.

Key words

Globalisation, international trade, transportation, communication, information technology, political & economic & cultural globalisation, deglobalisation, slowbalization.

I. Introduction: Meaning of Globalisation

Scholars have debated the phenomenon of globalization for several decades, although there has not always been agreement on what it means and some even doubting whether it exists (Held and McGrew, 2003; Scholte, 2005).Most scholars, however, accept that globalization is a reality, although there still questions as to when it began and whether the current phase is something that is really new. Furthermore, the phenomenon also has a normative dimension: is it a good or bad thing? There are strong arguments for and against. More recently, the debate has shifted to whether globalization has come to a halt or even reversed, if this is the case, why is this happening today? This topic, known as ‘deglobalization’, has also been hotly debated (Paul, 2021). This paper accepts the majority position that globalization is a reality and has brought many positive benefits but argues that we are today in a new phase.

First and foremost, what is globalization? It can be defined as the process through which goods, services, capital, technology, knowledge, and ideas are disseminated rapidly across the world. In other words, globalization constitutes a complex network of interconnectedness, interaction, and interdependence of everything and everyone, wherein distance of time and space between people have become increasingly insignificant. It facilitates the swift and seamless global mobility of people, capital, technology, goods, and services. Essentially, globalization can be understood as the emergence of a ‘borderless world’, in which national and state boundaries have become increasingly permeable.

II. History of Globalisation

The term itself appeared in social science discussions as early as the 1940s and then became more frequent in the 1960s and 1970s (Scholte, 2005), but it became widespread in the 1980s and 1990s reflecting global geopolitical and economic changes during this period. Some authors at that time argued that globalization wasnot new,buthad existed in phenomena such as the Great Silk Road which connected China with the Mediterranean world from the 1stcentury BC to the 5th century AD and again during 14th and 15th centuries AD. Other examples of early globalization were the voyages of discovery in the 15th and 16th centuries when Spanish, Portuguese, and English explorers such as Christopher Columbus, Ferdinand Magellan, and Sir Francis Drake discovered lands then unknown to Europeans and opened the way to a more global understanding of the world (indeed the awareness that the world was a globe and not flat as had earlier been thought), as well opening up trade routes across the oceans (Scholte, 2005).

This was also the beginning of the first phase of Empire-building by European powers,Spain, Portugal, England, and the Netherlands, whose domains would eventually cover almost the entire planet. Imperialism has been seen as a form of globalisation (Hardt & Negri, 2003) and the 19th century saw a new wave of empire-building as France, Germany, and Italy occupied territories in Africa and elsewhere.

Despite these claims that globalization is not new but quite ancient, the Peterson Institute for International Economics (2024) distinguishes two waves of globalisation. It argues that it was not until the 19th century did global integration take off. Following centuries of European colonization and trade activity, that first ‘wave’ of globalization was facilitated by steamships, railroads, the telegraph, and other breakthroughs, and by increasing economic cooperation among countries. The globalization trend eventually waned and crashed in the catastrophe of World War I, followed by postwar protectionism, the Great Depression, and World War II. After World War II in the mid-1940s, the United States led efforts to revive international trade and investment under negotiated ground rules, starting a second wave of globalization.

Although globalization has historical roots dating back to early regional and international trade networks, it accelerated dramatically by the late twentieth century, driven primarily by two transformative forces.The first key driver was advances in transportation. This was already present in 19th century with the introduction of steamships and railways. The motor car and air flight arrived at the beginning of the 20th century and horse-drawn transport gave way to the use of cars, buses and lorries, and the construction of huge highway networks. In addition, developments in aviation made possible that large numbers of passengers and big amounts of goods could be moved over long distances very quickly. The two World Wars, besides causing widespread destruction and loss of life, were also seedbeds of innovation and technological development with further developments in motor transport, more sophisticated airplanes, helicopters, and rockets, the invention of radar and sophisticated communications system. Science was applied to warfare, but had many spinoffs that would enter into everyday economic and social life. All of this accelerated after the Second World War with the invention of atomic energy, space travel, satellites, and increasingly swift transport systems.

However, it was not until the 1980s that the term ‘globalization’ gained popularity and in particular in the early 1990s. Why was that?

Globalization, encompassing not only the trade of goods and services or the movement of people,but also the spread of capital, technology, knowledge, culture and ideas,very rapidly on a global scale, began to accelerate in the 1980s. But why during this period? This surge was largely driven by the high-tech revolution and advancements in innovation, including the development of computers, cable networks, satellites, and information technology. Thus, the second driver responsible for shaping globalization was the communication&information technology (technologies revolutionthat began in Silicon Valley in California). At the beginning of the 1990s, another significant technological breakthrough entered the scene creating a truly global world of communication and interaction – the invention of the Internet, allowing people and businesses to communicate instantly. The 21st century has seen huge leaps in communication technology.Personal computers and especially the mobile phones, enabled people to communicate and to access the internet wherever they are. In the last decade, communication went to next level with social media, bringing people from all around the world in contact with one another.

When scholars began to debate the globalization of the 1990s, they were divided into three principal groups: a)those who argued that this was nothing new but, as has been described above, is actually a very old phenomenon; b) those who argued that the globalization of the 1990s was a specifically new phenomenon compared to previous globalization (Held, Scholte and others); c) and, finally, some who argued that in fact there was no globalization (Hirst and Thompson, 2003, 98-105). This last group rejected globalization because, according to them, nation-statesare still the key actors in international relations and politics, while the advocates of a ‘new’ globalization argued that this was undermining nation-states.

Most social scientists today agree with Held and Scholtethat there has indeed been a new globalization. However, the problem remains of defining what the term means as different definitions of the term may explain the lack of agreement referred to above.Here we distinguish different types of globalization, which are distinct, but also interact with each other.

III. Types of Globalization

Economic globalization.

This represents one of the earliest forms of globalization, historically evident through international trade. In contemporary terms, economic globalization refers to the increasing interdependence of national economies, driven by the expanding scale of cross-border trade in goods and services, the flow of international capital, and the rapid dissemination of technology. As a result, national economies are becoming increasingly integrated into a highly interconnected global economic system.

Economic globalization manifests in three key forms:

- Transnational Companies (TNCs) or Multinational Corporations (MNCs):They have become the main carriers of economic globalization (Shangquan: 2000). TNCs relocate manufacturing operations overseas, often to regions where labor regulations are less stringent, wages are lower, labor costs are more competitive, andlabor force is cheaper.

- Internationally Mobile Labor Force: Individuals with in-demand skills can access employment opportunities and find work across the world fast and easily.

- Global Financial Markets: The growth and increasing integration of financial markets enables capital to move freely across borders, influencing global economic trends.

Figure 1: An example of MNC – Toyota, which operates manufacturing and sales facilities across the globe.

When scholars speak of globalization, they often refer to the economic dimension. The advocates of the new globalization relate this to transformations which took place in the late 1960s and early 1970s which saw the end of the dominant Keynesian model of economic policy with the collapse of the Bretton Woods Agreement in 1971, when President Nixon announced that the United States would no longer convert dollars to gold at a fixed value (Eichenberg, 2019, p. 124-7). This eventually led in the 1980s to neo-liberalism, promoted by Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, which replaced the Keynesian model and shifted the focus in economic policy from a state-based approach to a market-based one. This became known as the ‘Washington Consensus’ (see below for an outline of the main tenets of this). The International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank (WB), the institutions of global economic governance established in the 1950s, now shifted from an approach informed by Keynesianism to one underpinned by the ‘Washington Consensus’. Economic production has been primarily associated by the economies of nation-states. With the new globalization, there emerges for the first time truly global economies in specific fields, such as banking, and in certain sectors of production although it remains true that all economic production is located somewhere geographically (Dicken, 2003). Economic globalization is primarily measured by trade flows, reflecting the increasing interconnectedness of national economies through the exchange of goods, services, and capital. This economic integration has promoted global business and investment, fostering economic growth and development across borders.

An important feature of this aspect of globalization is that it has permitted countries such as Brazil, Russia, China, and South Africa (known as the BRICS) to join the economic system of Western countries dominated by the USA and Europe, while previously they had been excluded or excluded themselves, from this. The collapse of the USSR and its communist satellites in the 1990s accelerated this type of globalization. For various reasons, the former communist states such as the Balkans, such as those that emerged from the former Yugoslavia, failed to capitalise on the opportunities that the new globalization presented in the way that the states of the Far East and Latin America did.

It is important to distinguish between the financial and the economic dimensions of globalization. Economies are still today largely nationally based. Economics as a discipline calculates economic processes by referring primarily to national economies. As mentioned earlier, there have been some truly global economic processes in some markets such as services. But the bulk are still nationally based. Even MNCs have their headquarters in particular countries although their diversification across several countries allows them sometimes to escape government regulation and taxation. The global financial markets are rather different and from the 1990s these took on a life of their own with banks developing new financial instruments and derivatives which really did escape government regulation. This was one of the factors that led to the 2007/8 Financial Crisis which subsequently began to affect national economies.

A key implication of economic globalization is the diminishing ability of national governments to regulate their economies independently, to manage their own economies, and to resist neoliberal market policies. Consequently, many scholars argue that globalization aligns closely with neoliberalism for two primary reasons:

- Shared Principles: Both emphasize competition, efficiency, productivity, and flexibility.

- Economic Policies: Both advocate for open markets, free trade, capital market liberalization, and flexible exchange rates.

By the end of the 1990s, neoliberalism had emerged as the dominant and largely unchallenged ideology of the new world economy.

Political globalization.

Political globalization refers to the increasing degree of political cooperation among nations. It is reflected in the establishment and growing influence of international organizations, which exercise jurisdiction not only within individual states, but also across multiple countries or entire regions. The underlying rationale for these “umbrella” organizations is that they are better equipped than individual governments to address and resolve global challenges and conflicts.

However, political globalization has also led to a decline in national sovereignty, as states increasingly cede authority to supranational institutions. This has raised concerns about the erosion of the traditional nation-state and its ability to independently govern its affairs.

The most significant types of international organizations include:

- Political and Security Organizations: United Nations (UN), North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), European Union (EU), Council of Europe (CoE).

- Economic Organizations: World Bank (WB), World Trade Organization (WTO), International Monetary Fund (IMF), Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

- Cultural Organizations: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

One of the most important transformations that occurred with the arrival of the new globalization was a reconfiguration of the place and role of the nation-state and national governments in the international Westphalian system of international relations. The old Keynesian model had placed central governments as the key actors in economic policy and management even if this varied according to distinctive state traditions. The underlying rationale of Keynesianism remained the same: the state should dominate both markets and society. Neo-liberal globalization did not abolish nation-states as some of the more extreme analyses claimed (Ohmae, 1995),but it did undermine its central position and permitted other actors such as international organizations, most notably the IMF and WB, and in Europe the European Union (EU), and even subnational authorities to rival its sovereign status. This has been described as a system of ‘Multilevel Governance’ (Marks and Hooghe, 2001).This led to a new development of global governance institutions and structures (Wilkinson and Hughes, 2002). The new global governance encompasses the formation and operation of international organizations, and the treatiesand agreements that shape global policies and regulations.

The advocates of strengthened global governance argue that this aspect of globalization facilitates cooperation and coordination among nations to address global challenges such as climate change, security, and human rights. On the other hand, critical perspectives point to the declining role of national governments and particularly the deregulation that accompanied neo-liberal globalization. One of the longer-term consequences of this deregulation was the financial crisis of 2007/8 which led to the Great Recession of that period. It was clear that globalized banking processes had largely escaped governmental regulation and failed to prevent the melt-down. Subsequently, central governments and organizations such as the EU began to tighten up their fiscal procedures and even to re-centralize their economic and financial control mechanisms (Callanan and Loughlin, 2021).

Cultural globalization.

Cultural globalization refers to the process by which information, goods, and images produced in one region of the world circulate globally, leading to a diminishing of cultural differences between nations and societies. As a result, people dress, eat, speak, and think similarly everywhere. This trend promotes cultural homogeneity and uniformity, often at the expense of national traditions and identities, withlocal cultures fading away.

This refers to the spread of values and ideas across the globe. In practice, this means Western values and ideas. Therefore, this phenomenon is frequently describedas ‘Americanization’ or ‘McDonaldization’, highlighting the dominance of Western, particularly American, cultural influences. Cultural globalization has been significantly accelerated by advancements in transportation, making international travel more affordable, and by the rapid development of information technology (IT), including the internet, satellite communication, and telecommunications.This has been helped by the extraordinary development of communicationstechnologies mostly in Silicon Valley in California, but in the UK and France as well.

In the contemporary era, social media has further intensified this process, amplifying the reach and impact of global cultural influences. From the early successes of the internet and email, these have expanded to platformssuch as Facebook, X/Twitter, and TikTok (McChesney, 2003). The use of new social media by political actors such as Obama on the Left and Trump on the Right show how effective they can be (Hendricks and Denton, 2010; Francia, 2017). Although these technologies originated in the West, countries such as China have adopted and developed them and now use them as means of influencing Western societies. Russia, for example, has been heavily involved in cyber-attacks on Western states to undermine Western democracy (Greenberg, 2020). Cyberwarfare has thus become a new theatre of warfare which is perhaps even more dangerous than conventional warfare especially with the most recent developments in Artificial Intelligence (Clark, 2003).

Social globalization.

This is most clear in patterns of cross-border migration. Cross-border migration has always been a feature of human settlement, and in the 1950s and 1960s the post-war economic recovery in Western Europe attracted many economic migrants to bolster the labour forces of these countries. Since the 1980s, however, and particularly since the 1990s, with the collapse of the communism in USSR and Eastern Europe and the enlargement of the European Union, there has been an even more massive influx of economic migrants from east to west. In 2010, the Arab Spring and Western intervention led to further intensive migration into surrounding countries especially Turkey and Europe as a result of the conflicts and wars and the rise of groups such as Islamic State.

It is sometimes argued that these movements of people across countries and continents contributes to the creation of multicultural societies, where individuals and communities interact and coexist. This has been the case when the migration flows have been carefully managed such as in the United States and, even there, the integration of early migrants such as the Irish, Italians, and Germans in the 19th century at times led to conflict. Overall, however, the US did prove to be a ‘melting pot’ in which the different groups in the end became loyal Americans while retaining some of their original identities.

In contrast, the more recent waves of migration in Europe have been less carefully managed,giving rise to a range of new challenges, which Bogdani (2009) categorises as below:

- The complexities of multiculturalism

- Issues of integration of immigrants into hosting societies.

- The threatto national security.

- The rise of nationalist political movements and right-wing parties.

Multiculturalism initially meant the co-existence of different cultures andthe recognition of cultural diversity of communities living in harmony together.However, in contemporary discourse, it increasingly denotes not only tolerance of cultural diversity but also demands for legal recognition of ethnic, racial, religious, and cultural rights. As Francis Fukuyama (2006) argues, “The hosting societies could get along with it as long as it does not challenge the liberal social order and is not a threat to liberal-democracy”.However, some immigrant communities have advanced demands or engaged in actions that are incompatible with liberal democratic principles, in some cases even challenging the secular order. This has led to growing hostility among European populations, who argue that multiculturalism has weakened national identities, disrupted traditional ways of life, and diminished the role of religion in public life. This has led, not to vibrant multicultural societies, but to societies divided into different communities and marked by high levels of social conflict.

Integration, on the other hand, refers to the process by which ethnic communities adopt the cultural identity of their host country. In Europe, this primarily applies to Muslim and other immigrant groups. However, a lack of successful integration has often resulted in the formation of segregated communities, where immigrants live parallel lives in enclaves among their compatriots. As Robert S. Leiken (2005) observes, “they are European citizens in name only, but not culturally or socially”. Francis Fukuyama (2006) considers the integration of immigrant minorities (particularly those from Muslim countries) as citizens of pluralistic societies, the most serious longer-term challenge facing liberal democracies today.

The growing dissatisfaction among Europeans with the failure of immigrant integration, the perceived excesses of multiculturalism, and the pervasivePC (political correctness), have contributed to the rise of right-wing and far-right populist parties (Bogdani, 2009). This resurgence of nationalist movements is evident not only in political discourse, but also present in mainstream politics, in national parliaments and governments.The electoral success of some of these parties in various national elections, as well as victory in the last 2024 European elections, where nationalist, populist, and far-right parties gained substantial support, showed that these parties are popular and loveable, particularly among native populations. The reason for this is because they advocate for the preservation of European heritage and European national identities,the protection of traditional cultural values, and the reinforcement of Christian-secularist principles against the perceived threat of Islamization.Their victories reflect widespread concerns among European populations over immigration, cultural change, and national identity, prompting calls for stricter immigration policies and renewed emphasis on safeguarding Europe’s historical and cultural legacy.

This in turn has placed the democratic systems of the EU under strain. The prospects of joining the EU for those candidate countries which are seeking membership have become so much more difficult as the elites of the EU and the current member states are wary of causing further backlashes such as occurred in the UK with the Brexit vote to leave the EU in 2016 (Mudde and Kaltwasser, 2018).

IV. Implications of Globalisation

Globalization has far-reaching consequences, bringing both positive and negative implications for societies worldwide.

Positive Implications

Globalization offers numerous benefits and advantages, which can be categorised into economic, cultural and social dimensions, as outlined below.

Effects of globalization on economic development (Research FDI: 2023) include:

Increased trade and investment opportunities: This has led to higher levels of economic growth and development.

- Access to new markets and customers: This has helped to boost sales and profits.

- Greater efficiency and productivity: Globalization has increased competition among businesses, which has driven innovation and efficiency.

- Increased competition: This has led to lower prices and higher quality products for consumers.

- Spread of new technologies and knowledge: Globalization has facilitated the spread of new technologies and knowledge across borders, allowing countries to learn from one another and adopt best practices.

- Transnational companies in lower income countries:This can help to improve the local economy and provide new jobs and skills.

Effects of globalization on cultural dimension:

- Greater tolerance and understanding: Exposure to diverse cultures fosters mutual respect and global awareness.

- Cultural coexistence: Different cultures interact and influence one another, promoting multiculturalism.

- People can experience new countries and cultures around the world due to the media and better transport.

- Access to new cultural products: Globalization enhances exposure to cultural elements such as art (greater access to diverse artistic works and expressions) and entertainment (wider availability of global media, films, and music).

Effects of globalization on social dimension:

- Increased convenience: It simplifies daily life through technological advancements and global integration.

- Easier communication: The widespread use of the English language facilitates global connections.

- Access on education: Expansion of international academic exchange and learning opportunities.

Negative implications

Despite its advantages, globalization also presents several challenges. Alongside the positive impacts, globalization has also brought about a range of negative impacts on economic development (Research FDI: 2023), as well as on culture and social life.

Economic dimension:

·

- Loss of jobs and industries in some regions: because of the relocation of industries and jobs to countries with lower labor costs.

- Widening income inequality: between and within countries, with some countries and individuals benefiting more than others.

- Vulnerability to global economic downturns: Globalization has increased the interconnectedness of economies, making them more vulnerable to global economic downturns and crises.

- Small businesses are forced to close, due to the competition from global chain stores.

Cultural dimension:

- Cultural homogenization: Globalization has led to the spread of Western culture and values, which has resulted in the homogenization of cultures and the loss of traditional cultures.

- Often referred to as the “global monoculture,” globalization diminishes cultural, social, economic, and political diversity. People worldwide watch the same TV programs and films, buy the same things, wear the same clothes, eat the same food, and adopt uniform lifestyles.

- Loss of national identities: The increasing influence of global norms and institutions can weaken the sense of national belonging.

- Erosion of local cultures: Traditional customs, languages, and cultural practices risk being overshadowed by dominant global influences.

Social dimension:

- Environmental degradation: Increased trade and economic activity has led to higher levels of pollution, deforestation, and climate change.

- Global risks: The interconnected nature of globalization exacerbates various transnational threats, including:

- Pandemics – The rapid movement of people and goods accelerates the spread of infectious diseases.Diseases such as Covid-19 can spread from one country to another far easier with so many people and goods moving around the world.

- Terrorism – Global networks facilitate the organization and execution of transnational terrorist activities. As Bogdani (2009) argues, globalisation, driven by the Internet and the tremendous modern mobility, has blurred the boundaries between the developed world and traditional Muslim societies. The proximity brought by globalisation is inherently dangerous when cultures are different. It is not an accident that so many terrorists were either European Muslims or came from privileged sectors of Muslim societies with opportunities for contact with the West.

- Drug and Human Trafficking – International criminal networks exploit globalization to expand illicit trade and exploitation.

Therefore, wide-ranging effects of globalization are complex and controversial. As with major technological advances, globalization has delivered benefits to the world’s societies, but has been the target of criticism for allegedly harming certain groups and aggravating inflation, supply chain disruptions, trade disputes, and national security concerns (Peterson Institute for International Economics, 2024).

V. Phases of Globalization

It is useful to sketch out the changing historical context in which different phases of globalization occurred and to analyse the different features of each phase.

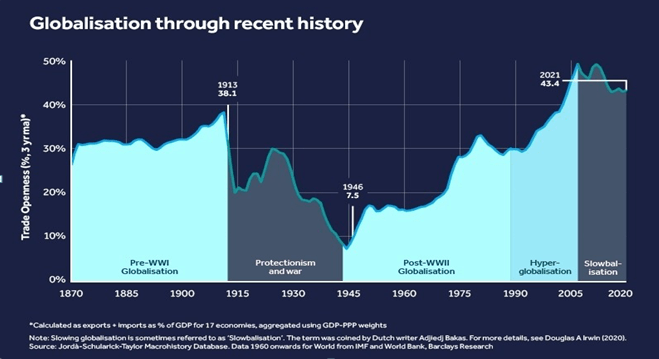

Figure 1: Globalization through recent history.

Source: World Economic Forum.

What is striking in this history of globalization is the accelerating pace of change. This can be seen in the diagram in Figure 1 which distinguishes distinct periods:

Globalization 1.0 (pre-World War I).

This period of globalization was driven by two principal factors: first, the expansion of new phase of imperialism by Western countries such as England, France, and Germany; and second, by the dynamism of the Industrial Revolution with the US, Europe, Argentina, and Australia as the principal forces. The resulting global trade exchange was facilitated by the gold standard and lower transportation costs.

Globalization 2.0 (post-World War II).

Phase 1.0 ended with the outbreak of the WWI and the interwar period was marked by economic nationalism and retrenchment, the Great Depression and the rise of Fascism, Nazism, and Soviet Communism, all leading to WWII. Following WWII, however, we enter the phase of post-war economic reconstruction, with the United States emerging as the new superpower while the European empires begin to unravel. This is a period internal state and economic expansion in the Western powers, as the combination of Keynesian economic policies and the founding of Welfare States led to the emergence of strong states. The founding of the European Economic Community in the early 1950s, far from undermining the nation-state, served in fact to strengthen it (Milward, 2000). Although Western countries dominated by the US created the conditions of global trade, the Cold War divisions of international politics prevented true globalization, as major powers such as the USSR and China remained outside the emerging global system.

Globalization 3.0 (late 20th century).

The crises of the 1970s which saw the collapse of the Bretton-Woods Agreement as outlined above and the arrival of a dominant neo-liberalism known as the ‘Washington Consensus’ (Marangos, 2020), whose key tenets typically include:

- Fiscal discipline to avoid large fiscal deficits.

- Reorientation of public spending from subsidies toward broader social services like health and education.

- Tax reform, aimed at broadening the tax base and ensuring moderate marginal tax rates

- Interest rate liberalization to ensure market-determined interest rates.

- Competitive exchange rates to facilitate export growth.

- Trade liberalization, reducing tariffs and non-tariff barriers.

- Openness to foreign direct investment (FDI).

- Privatization of state-owned enterprises.

- Deregulation to remove barriers to entry and competition.

- Secure property rights to ensure legal ownership and usage.

This period was marked by the creation of truly global markets in certain services and goods and, not least, in banking, where new financial tools such as derivatives were traded in global markets away from the regulation by national governments and banks (Castells, 2003). The foundations were thus being laid for the subsequent financial crisis.

Globalization 4.0 (hyper-globalization).

The collapse of communism in the USSR and its former satellite states in Eastern and Central Europe, as well as Yugoslavia and Albania, ushered in a new phase of globalization which was dubbed ‘hyper’-globalization.China and other states such as North Korea, Vietnam, and Cuba did not give up communism, but China decided to join the global capitalist system and, as a result, became one of the leading players in world politics (McGrew, 2011). Although digital technologies had been present throughout the rise of the new globalization, their development accelerated at an even greater pace than previously and their application to real life economic processes and social interactions intensified. This enabled remote work and international telecommuting which transformed the service sector thus creating new opportunities and challenges. Productions processes and supply chains became highly integrated across borders and led to significant economic interdependence (Castells, 2003).

VI. Slowbalization, Deglobalization, and Regionalization

The period of ‘hyperglobalization’ ended with the Great Recession of 2007/8 and then with the Covid-19 pandemic, which brought the world almost to a standstill and from which we are now recovering. There is a debate as to whether this has led to ‘deglobalization’,with some contesting the idea (e.g. Altman et al. 2024), and with other prominent economists accepting that it is occurring (e.g. James, 2017).

At the very least, we can say that globalization is slowing down even if it not reversing. The term ‘slowbalization’ was coined by Teyvan Pettinger in a blogin 2017 (Pettinger, 2017).The advocates of slowbalization and deglobalization highlight the following features of the change:

- Reduced global trade.

- Reshoring, onshoring, and friendshoring: governments and companies are bringing production and supply chains closer to home to reduce dependency on foreign suppliers (for the West, especially dependency on China).

- Regionalization of trade: there has been a trend towards regional trade agreements and partnerships.

- Technological decoupling: countries are investing in their own high-tech industries which is especially evident in US-China (even US-Taiwan) relations.

- Focus on resilience and security: countries emphasize strengthening their own security chains.

- National governments are trying to regain control over their own economic and financial systems: this is a reaction to the loss of control that had led to the financial and economic crises of 2007/8.

These developments pose challenges to world and regional political systems. Aspects of globalization, as we have seen, contributed to the rise of populist movements of both left and right in the EU member states and, in the UK at least, led to Brexit and the departure of the UK from EU membership. Similar political movements can today be found in several of the Member States including the longest serving members such as France, Germany, the Netherlands, and Italy. The EU’s response to these challenges has been to attempt to strengthen its democratic credentials, both atmember-states level and at the EU level. But they have also led to a rethinking of the EU’s future and particularly its appetite for further enlargement toward the Balkans and Turkey, both of which are candidates for membership. It remains to be seen whether there will be ‘slowbalization’ of the enlargement procedure. Many EU member states, particularly France and the Netherlands, have expressed skepticism about further enlargement due to concerns over governance, corruption, and economic disparities in candidate countries. This reluctance has resulted in stalled accession talks, as seen with North Macedonia and Albania. President Macron has repeatedly emphasized that the EU must deepen integration before expanding further. His 2019 veto of North Macedonia’s and Albania’s accession talks illustrates how domestic political priorities in France shape EU policy. Germany has traditionally been a pro-enlargement advocate.It sees Balkan stability as crucial for European security. However, domestic concerns about migration and economic disparities have tempered enthusiasm for rapid expansion. On the other hand, some member states from the former East European bloc like Hungary and Poland often support Balkan enlargement, partly to strengthen the influence of conservative and Eurosceptic voices within the EU (Bogdani & Loughlin, 2007).

Conclusions

Globalization is a multifaceted and complex phenomenon, commonly defined as a network of interconnectedness, interaction, and interdependence. It has enabled the rapid transnational movement of goods, services, people, capital, technology and culture, rendering traditional notions of time and space increasingly irrelevant. Although globalization has historical roots dating back to early regional and international trade networks, its scope and intensity expanded dramatically by the late twentieth century, driven primarily by two transformative forces: advancements in transportation, and more significantly, innovations in communication and information technology.The early 1990s marked a turning point with the advent of the Internet, followed by the widespread use of personal computers and mobile phones, all of which revolutionized global communication. The emergence of social media in the past decade has further accelerated the pace and depth of globalization.Globalization manifests in four primary dimensions: economic, political, cultural, and social, each characterized by distinct features and expressions. Its influence has generated profound implications for states, governments, societies and individuals alike. While globalization has delivered significant economic growth, cultural exchange, and social transformation, it has also given rise to notable challenges and deepening global inequalities. Globalization has evolved through several distinct phases: the pre-World War I era, the post-World War II period, the late twentieth century, and the current phase often referred to as ‘hyper-globalization.’ Each of these periods is marked by unique characteristics and has exerted a significant impact on global dynamics.The era of hyper-globalization has, in recent years, led to growing discourse on ‘deglobalization,’ with scholars divided between those who challenge its occurrence and those who assert that it is already underway. A related concept gaining traction in academic debate is that of ‘slowbalization,’ which refers to a deceleration of global integration, as exemplified by critical events such as the 2007–2008 financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic. These disruptions have raised fundamental questions about the future trajectory of globalization.Nevertheless, despite increasing discussions about its potential stagnation or reversal, globalization persists as a defining and enduring feature of contemporary global society, one that continues to deliver considerable benefits to humanity.

REFERENCES

Altman, Steven A., Caroline R. Bastian, and Davis Fattedad (2024), “Challenging the Deglobalization Narrative: Global Flows Have Remained Resilient through Successive Shocks.” Journal of International Business Policy, Vol. 7, no. 4 (2024): 416–439.

Bogdani, M. & Loughlin, J. (2007), Albania and the European Union: The Tumultuous Journey towards Integration and Accession.I.B.Tauris: London – NY.

Bogdani, M. (2009), Turkey and the Dilemma of EU Accession: When Religion meets Politics.I.B.Tauris: London – NY.

Callahan, Mark and Loughlin, John (2021), (eds.), A Research Agenda for Regional and Local Government, Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Castells, Manuel (2003), “Global Informational Capitalism”, in Held and McGrew, op. cit., pp. 311-334.

Clark, Ian (2003), “The Security State”, in Held and McGrew, op. cit., pp. 177-8.

Dicken, Peter (2003), “A new eco-economy”, in Held and McGrew, op. cit.,pp. 303-310.Eichenberg, Barry, Globalizing Capital: a History of the International Monetary System, 3rd edition, Princeton, Princeton University Press.

Francia, Peter L. (2017), “Free Media and Twitter in the 2016 Presidential Election: The Unconventional Campaign of Donald Trump”, Social Science Computer Review,Vol.36, no. 4, August 2018, pp. 440-455.

Fukuyama, F. (2006), “Identity, Immigration, and Liberal-democracy”. Journal of Democracy 17/2. pp. 5-20.

Greenberg, Andy (2020), Sandworm: A New Era of Cyberwarfare and the Hunt for the Kremlin’s most dangerous hackers, London, Penguin Random House.

A NEW ERA OF CYBERWAR AND THE HUNT FOR THE KREMLIN’S MOST DANGEROUS HACKERS

Hardt, Michael and Antonio Negri (2003), “Globalization as Empire”, in Held and McGrew, op. cit., pp. 116-9).

Held, David andAnthony McGrew(2003), (eds.), The Global Transformations Reader: An Introduction to the Globalization Debate, 2nd edition, Polity Press, Cambridge, UK.

Hendricks, John Allen& Denton, Robert E. Jr. (2010). Communicator-in-Chief: How Barack Obama Used New Media Technology to Win the White House. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books.

Hirst, Paul and Graeme Thompson (2003), “Globalization – a Necessary Myth”, in David Held and Anthony McGrew (eds.), The Global Transformations Reader: An Introduction to the Globalization Debate, 2nd edition, Polity Press, Cambridge, UK.

Hooghe, Liesbet and Marks, Gary (2001),Multi-Level Governance and European Integration Lanham, M.D.: Rowman & Littlefield.

James, Harold (2017), “Deglobalization as a Global Challenge”, CIGI Papers no. 135, Waterloo, Canada:Centre for International Governance Innovation.

Leiken, R. (2005), “Europe’s Angry Muslims”. Foreign Affairs, Vol.84, No.4, pp.120-35.

Marangos, John (2020), International development and the Washington Consensus / John Marangos.London : Routledge.

McChesney, Robert W. (2003), “The New Global Media”, in Held and MCrew, op.cit. pp.260-277.

McGrew, Anthony (2011), “Globalization and Global Politics”, in John Baylis, Steve Smith and Patricia Owens, (eds.), The Globalization of World Politics, Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 14-31.

Millard, Alan S. (2000), Routledge,London & New York, 2000.

Mudde, Cas and Cristobal Rovira Kaltwaser(2018), “Studying Populism in Comparative Perspective: Reflections on the Contemporary and Future Research Agenda”, in Comparative Political Studies, Vol. 51, No. 13, pp. 1667-1693.

Ohmae, Ken’chi (1995), The End of the Nation-State: the Rise of Regional Economies, The Free Press, New York.

Paul, T. V. (2021), “Globalization, deglobalization andreglobalization: adapting liberalinternational order”, International Affairs, Vol. 97, no. 5, pp. 1599–1620.

Pettinger, Teyvan (2017), Economics Help.

https://www.economicshelp.org/blog/166776/economics/slowbalisation-is-globalisation slowing-down/

Peterson Institute for International Economics (2024), “What is Globalisation?”, 16 August.

Bottom of Form

Research FDI (2023), “The effects of globalization on economic development”, 11 April.

Scholte, Jan Aart (2005), Globalization: A critical introduction.2ndedition revised and updated, Palgrave MacMillan, Basingstoke, UK.

Shangquan, Gao (2000), “Economic Globalization: Trends, Risks and Risk Prevention”, Economic and Social Affairs. CDP Background Paper No.1.

Wilkinson, Rorden and Hughes, Steve (2002), (eds.), Global Governance: Critical Perspectives, Abingdon, Routledge.

[1]University of New York Tirana, Department of Politics & IR. Albania. mirelabogdani@unyt.edu.al

[2]University of Cambridge & Cardiff University, United Kingdom. jl602@cam.ac.uk