Abstract

Labor immigration has been the focus of Serbia’s governmental agendas for years now. The labor regulations related to immigrants have been amendedmost recently in 2023 to attract and utilize to the fullest the potential of immigrant laborers. Whereas the legislation is partially in compliance with the EU acquis, the implementation thereof has struggled with numerous challenges to result in a rather low proportion of immigrant laborers on the national labor market. In the introductory part of the paper, we present in brief the overall situation on the national labor market. After that, we explore the national labor market characteristics and accompanying legislation concerning immigrant laborers. This is followed by the presentation and comparison of data on immigrant laborers, as well as their factual situations on the labor market. In the concluding part we point to further considerations of importance for the topic, first of all regarding future challenges for the labor immigration to Serbia, calling for more extensive measures of empowering immigrant laborers to integrate into society. The deployed methodological approach consisted of the desk review, including the review of the relevant legislations, description and analysis of the statistical data and reports from the relevant stakeholders.

Keywords: employment, immigration, immigrant laborers, labor migration, labor market, labor legislation

Introduction

In recent decades, Serbia’s economic development has been characterized by a relatively unstable relationship between economic growth and labor market performance, frequently framed under “growth without development” (Perišić 2016). The consequences thereof started to be experienced as of 2008, when the world economic crisis of 2007 showed to present a long-lasting threat to achievements in the sphere of human development realized in the period from the beginning of the 2000s (Arandarenko, Jorgoni, Stubbs 2009). The end of this decade was marked by high concerns about the labor market performance, which was characterized by a shrinking economy resulting in declining employment and increasing unemployment and poverty (Vuković, Perišić 2011). After 2012, which saw the employment rate as low as 35.5% and unemployment rate of as high as 23.9% (Republičkizavod za statistiku 2015), labor market indicators started to significantly improve to result in an employment rate of 51.4% and unemployment rate of 8.6% in the last quarter of 2024 (Republičkizavod za statistiku 2025). Whereas the low unemployment rates partially mask high inactivity rates, the employment rates, and even more, the characteristics of employment, are worrisome.

Numerous advancements in the national labor market, first of all, regarding the harmonization of the national legislation with the EU acquis, have been planned and gradually implemented within the context of Serbia’s aspirations towards EU membership. Serbia started its negotiations with the EU in 2012, but the progress in labor relations in general still remains limited.

The aim of this paper is to present and analyse characteristics of labor immigration in Serbia and the changes that occurred more recently as a result of the complex domestic and international circumstances. In the first part of the paper, we explain briefly the main impacts of the national legislation on labor relations on the labor market in general. Then, we present in more detail and analyze the regulations on the employment of immigrants in Serbia. The immigrants have been seen as a means to facilitate the complex demographic situation, resulting in shrinking and aging of the population in combination with high emigration rates of the young to middle-aged population, requiring additional workforce in certain sectors of the economy. In the second part of the paper, we present and analyze the structure of labor immigration to show that it cannot compensate for the high emigration rates. More importantly, we point to many violations of the rights of immigrant laborers. Throughout the paper, we present the challenges in relation to the legislation and its implementation, resulting in low attractiveness of the national labor market for labor immigration.

Labor Legislation – Between Innovation and Implementation Trap

In Serbia, labor relations are regulated through a series of laws, with the Labor Law of 2005 as a general law in this domain. The Law introduced the flexibilization of employment at the expense of labor security and adaptability and its subsequent amendments have been contributing to this trend irreversibly. For the last two decades, some of the most critical challenges in relation to the Labor Law and its implementation have been reflected in high rates of informal employment and undeclared work, with low capacities of the Labor Inspectorate to counteract illegal labor practices. Additionally, there is a recurring process of extremely aggravated transitions of informal laborers into official contractual employment, followed by increased numbers of fatalities and severe injuries with fatal consequences in certain industry sectors.Widely occurring phenomena of prolonging fixed-term contracts for an indefinite period of time has become a common practice, with almost absent social dialogue and involvement of laborers due to disempowered labor unions, and underdeveloped measures aiming to ensure a work-life balance for laborers (Perisic 2023).

In its country reports for Serbia, the European Commission has been continuously pointing to the deficiencies in relation to Chapter 19, which encompasses employment, including the last one for 2024 (European Commission 2024). The Labor Law is only partially in compliance with the EU acquis, and in combination with weak mechanisms for its implementation, its result has been an inefficient effectuation of the rights of both national and immigrant laborers in multiple ways. Clearly, Serbia performs below the EU average in the domain of labor relations, and especially fair working conditions indicators, but in comparison with other Western Balkan economies (Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo*, Montenegro and North Macedonia), its performance was above average (Ymeri 2023; Sarajlic 2023; Zylfijaj 2023; Mirkovic 2023; Nikoloski 2023; Perisic 2023). Contrary to this, the Law on Entrepreneurship of 2022, with its focus of social economy, vulnerable groups and social innovation, according to the first informal evaluations conducted, is harmonized with the EU regulations and especially with the Action Plan for the Social Economy (Perisic 2023), albeit missing important sublegal legislative to be implemented in full. It does not have special references to immigrant laborers, but the vulnerable groups are defined in extenso (article 6), so that vulnerable migrants can o be included.

Regarding the legislation regulating exclusively the labor migration, the Law on Employment of Foreigners of 2014 was adopted to encompass multiple categories of immigrant laborers, both EU[1] and non-EU nationals, as well as asylum seekers. It stipulates the equal rights and obligations of immigrants and Serbian nationals in the domains of labor and employment (article 5), but its norms are not fully in compliance with the principle of equality, as it will be elaborated further. The introduction of the latest amendments to the Law in 2023 was motivated by the harmonization of national legislation with the EU acquis and the necessity to facilitate highly complex procedures for the employment of immigrants that were previously in existence.

Novelties to the Law include the provision of a single permit for temporary stay and work for an immigrant (article 9), as well as the activity of the National Employment Service, such as assessment of an immigrant’s eligibility for employment (article 10), as a necessary precondition for employment. The assessment of an immigrant’s eligibility is prescribed to present a precondition for obtaining an employment-based visa for a longer stay (which is to enable an immigrant to enter Serbia, travel throughout the country, stay and work there). The Law also authorized the National Employment Service to issue a consent enabling an immigrant to change his/her employment (article 11).

The introduction of a single permit superseded the norms that differentiated as many as seven types of work permits. The new legislation digitalized the process of requesting and obtaining a single permit for stay and work with a view to lowering the administrative barriers, reducing costs and time consumed in the process. However, the implementation of the legal stipulation that an immigrant can apply only electronically for the permit was postponed already at the occasion of the Law enactment until February 1st, 2024, due to the inability to build an operational portal (Beogradskicentar za ljudskaprava 2024). Based on reports from January 2025, the portal was still not operational in full, the information for prospective immigrants was incomplete or lacking, sometimes outdated and not tailored to any of their specific circumstances. Two versions of the relevant website (the official and the trial one) were running in parallel and even the link for the application for the single permit was not functioning from the official website but could only be found by googling it (Daffini 2025). The amended Law also made the authorities liable to process the requests within 10 days (article 11). Finally, it is prescribed that a single permit does not necessarily have to encompass only one, but it can encompass more immigrants, and it can be issued, i.e., prolonged for three years, instead of one year as per the previous regulation (Urdarević, Misailović 2025).

And while the introduction of a single permit is in compliance with the EU regulations, more specifically the Directive 2011/98/EU, the difficulties in its implementation call for special precautions and the novelty regarding the legal provision of the so-called labor market test to be performed by the National Employment Service clearly interferes with this compliance. Namely, the National Employment Service is authorized to act as “an interregional mediator in employment by means of establishing whether there are already eligible persons that can be employed by a requesting employer” (article 16a). This norm serves as a protective measure against immigrant laborers and in favour of Serbia’s nationals. Still, certain categories of immigrants with deficitary occupations and professions can be omitted from the labor market test, based on the governmental decision, depending on the labor market situation (article 16a). Finally, the government is entitled to limit the number of immigrants to be employed, i.e. to introduce quotas, when there are labor market disturbances, in compliance with the migration policy and labor market trends (article 24).

The Law also enabled asylum seekers, persons authorized with asylum and temporary protection to effectuate their right to an employment 6 months after applying for an asylum, instead of previously prescribed 9 months. This novelty to the Law brings Serbian legislation more into compliance with the EU standards. The intended consequence is to facilitate their integration via employment. Still, this requires more specific active labor market measures to be deployed by the National Employment Service as well as more cultural sensitivity by the employers.

The Law on Employment of Foreigners made progress only in certain aspects, and in relation to Chapter 2 which encompasses freedom of movement for workers, the European Commission evaluated it as partially aligned with the EU acquis in its latest country report for Serbia (European Commission 2024).

Even before the latest amendments to the Law on Employment of Foreigners, the Regulation on Criteria for Incentives to Employers Employing Newly Inhabited Persons was enacted in June 2022 and amended in 2023. It is targeted towards deficitary occupations and professions and entitles employers who employ newly inhabited persons “the need for which cannot be easily satisfied on the national labor market” (article 2) to certain benefits. Newly inhabited are considered those who did not stay in Serbia for a longer period than 180 days in the period of 24 months prior to the open-ended employment contract signing for a wage of at least RSD 300,000 (around EUR 2,550), four times higher than the average wage in Serbia. Such employers are entitled to a return of 70% of paid taxes and to a full reimbursement of contributions paid for old-age and disability insurance (article 2). The purpose of the Regulation is to encourage talents to immigrate to Serbia by offering them special opportunities for being exempted from paying taxes and social contributions.

Labor Immigration in Statistics and Reality

International migration patterns have had a pronounced impact on the national labor market dynamics. The country has long exhibited complex migratory flows, with outward labor migration prevailing as the dominant form. Emigration has functioned as a socio-economic outlet for persons unable to secure employment aligned with their qualifications and skills within the national labor market. However, the continued outflow of working-age populations has contributed to a contraction of the labor supply, effectively reducing not only the number of job seekers but also the broader potential of the labor force (Medić et al. 2022). At the same time, consistent with the theory of Ernst Georg Ravenstein that “every migration flow generates a counterflow” (Langović et al. 2024, 2), Serbia found itself in a situation of the lack of labor force, which, along with other international complexities (the 2015 migration “crisis”, COVID-19 crisis, Russian invasion on Ukraine, etc.) influenced the numbers of immigrants in Serbia. The “door“ forlabor migration was opened already in the 1990s, mainly for the Chinese laborers, but their immigration remained on a rather small scale. It was the Law on Employment and Insurance in Case of Unemployment of 2009, which attracted foreign employers to the country by offering them extremely generous subsidies for starting their businesses in Serbia. This was frequently followed by the employment of their nationals (especially in the case of employers from Asia).

In Serbia nowadays, the immigrant population can be broadly divided into three groups (Republičkizavod za statistiku 2025):

- Persons granted temporary residence for a minimum duration of one year;

- Persons initially granted temporary residence for a period of less than one year, but who, through consecutive extensions, have maintained uninterrupted legal stay exceeding one year;

- Persons who have been granted permanent residence.

Asylum seekers, persons authorised with asylum and temporary protection, have a specific position, since the effectuation of their rights is dependent on the asylum procedure and the regulation of their legal status in the country. The challenges for asylum seekers stem from long-lasting asylum procedures, difficulties in applying for asylum, lack of support in the process and complicated procedures. Additionally, the vast majority of asylum seekers do not apply for asylum immediately upon arrival to Serbia, as they often plan to move to another country, most frequently in the EU, and rarely consider Serbia as their country of destination (IDEAS 2024). This influences their integration in society, including the integration into the labor market. The numbers of asylum seekers and people granted with refugee or subsidiary protection vary since 2015, but they are extremely low; the latest data show that 196 persons applied for asylum whereasnine of them got their asylum claims approved (Komesarijat za izbegliceimigracije 2024).

When compared to the preceding decade, 2023 recorded the highest number of foreign nationals residing in Serbia to date. The most prominent among these were those residing on the basis of employment, with a particular concentration in the information technology sector, as well as foreign nationals engaged in large-scale infrastructure development projects (Komesarijat za izbegliceimigracije 2024).

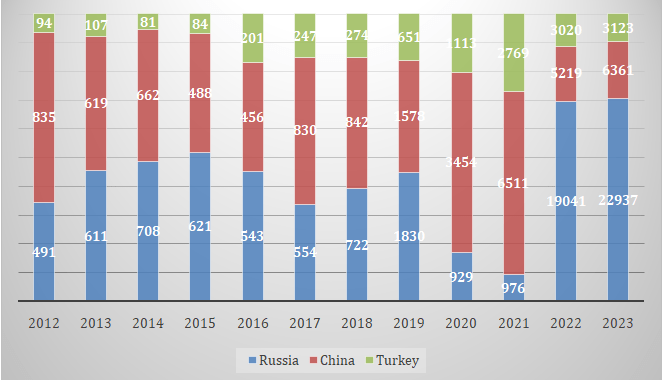

Citizens of the Russian Federation represented the largest group of immigrants (41,644), followed by citizens of the People’s Republic of China (12,157), Turkey and India. Notably, the total number of immigrants to Serbia in 2023 was approximately 9.5 times higher than in 2012. Citizens of the Russian Federation, the People’s Republic of China, Turkey, and India together accounted for 83.5% of all immigrants to Serbia in 2023. The number of Russian immigrants increased nearly 47 times compared to 2012, while the number of Chinese and Turkish immigrants rose approximately eight and thirty-three times, respectively, over the same period (see graph 1). Demographically, nearly two-thirds of all immigrants who arrived between 2012 and 2023 were male, while one-third were female. The average age of immigrants was on average lower than the national average (32.6 years), with the most significant difference observed in the Belgrade region, where the average immigrant age stood at 30.2 years (Republičkizavod za statistiku 2025).

Graph 1. Numbers of largest immigrant groups in Serbia, 2012-2023

Source: Adapted according to the Republicki zavod za statistiku (2025).

Employment remained the most common legal basis for granting temporary residence in 2023, accounting for 58.9% of all cases – mirroring the trend observed in the previous year (Komesarijat za izbegliceimigracije 2024). This development reflects both the continued arrival of foreign investors and the ongoing implementation of major infrastructure projects, as well as a structural shortage of labor within Serbia’s national labor market. Whereas family reunification was the predominant basis for residence at the beginning of the decade, recent years have seen a clear shift toward employment-based immigration. However, the increase in the number of residence permits issued based on family reunification can be attributed to the growing trend of entire families relocating to Serbia, particularly in cases where the primary residence permit holder was granted status on the basis of employment.

At the end of 2023, a total of 46,073 immigrants held valid temporary residence permits in Serbia based on employment. This figure represents a 29% increase compared to 2022, and a striking 121% increase compared to 2021, when 20,828 foreign nationals resided in Serbia on the same legal basis. Furthermore, the number recorded in 2023 is nearly 3.5 times higher than in 2020, when only 13,669 individuals held employment-based residence. Between January 1 and December 31, 2023, the National Employment Service issued a total of 52,178 work permits to foreign nationals, of which 9,875 were issued to women. The number of work permits issued to foreign nationals holding valid temporary residence in Serbia in 2023 amounted to 51,631, which reflects a notable increase compared to 2022, when 34,573 such permits were issued (Komesarijat za izbegliceimigracije 2024) (See table 1).

Table 1. Number of issued work permits and immigrants found without work permits during labor inspection

| Year | No of issued work permits | No of workers found without a work permit |

| 2024 | Not available | 611 |

| 2023 | 52,187 | 867 |

| 2022 | 35,174 | 630 |

| 2021 | 23,662 | 1354 |

| 2020 | 12,931 | 105 |

| 2019 | 13,802 | 32 |

Note: For years 2019 and 2020, the Labor Inspectorate did not include a special chapter on foreign workers’ rights. The data in the table are derived from the reports of the Labor Inspectorate, calculated and recorded in different parts of the reports, so that they should be taken with caution.

Source: Labor Inspectorate, different years, and Commissariat for Refugees and Migration of the Republic of Serbia, different years

As per the above Table, the highest share of immigrant laborers found by the Labor Inspectorate in undeclared work was as low as 5% in 2021. In the rest of the listed years, it accounted for less than 2%. On the one hand, it seems that the number of cases of malpractices to which immigrant laborers are exposed on the labor market is underestimated. On the other hand, the Labor Inspectorate reports that in all those cases in which immigrant laborers were found in undeclared work, employers did not translate them into formal employment (which is frequently the case with Serbia’s nationals), but employed new immigrant laborers (Perisic 2023), pointing to stubborn malpractices in cases of employing immigrants.

Between January and December 2024, labor inspectors in Serbia conducted 289 inspections related to the employment of foreign nationals. During these inspections, 7,482 labor immigrants were identified as being engaged in work activities, of whom 611 were found to be working without valid work permits. The majority of the undocumented workers originated from Turkey (425), followed by India (30), Tajikistan (24), Uzbekistan (19), and other countries, including Kyrgyzstan, China, Indonesia, Russia, etc. Among those found in breach of employment regulations, 338 immigrants were working informally, either without formal employment contracts or without registration for mandatory social insurance. The largest groups among them were citizens of Turkey (200), India (30), and Tajikistan (17), followed by workers from Russia, Bangladesh, Kyrgyzstan, China, Indonesia, etc. Turkish citizens have been the largest group identified in the past five years, whose labor rights are being violated through different forms of informal work (Inspektorat za rad 2025).

In addition, inspectors established that 668 of the detected foreign workers (approximately 9% of the total) were employed by foreign companies abroad and seconded to Serbia to perform contracted tasks for locally registered employers. The remaining 91% (6,814 workers) were directly employed by Serbian-based companies. These findings underscore persistent challenges in the regulation and oversight of foreign labor, particularly concerning legal employment status, social protection, and workplace safety standards. They also highlight the need for improved inter-institutional coordination between labor authorities and migration services, as well as stricter enforcement of employer obligations (Inspektorat za rad 2025).

Reports of the Labor Inspectorate show that the procedure for accessing the labor market in Serbia for asylum seekers dissuaded foreigners from pursuing asylum procedures in Serbia or forced them into the informal labor sector, thus heightening their vulnerability to further human rights violations (Inspektorat za rad, 2025). Additionally, there is strong evidence of child labor, especially among the unaccompanied children asylum seekers and migrants in Serbia, who are often involved in hazardous labor and the worst forms of child labor (Marković 2024).

There are several anecdotal reports compiled by the civil sector and reports of investigative journalists of violations of labor rights of immigrants. Even though these reports raise very serious allegations and concerns of exploitation and even trafficking of migrants from Turkey, India, China and Vietnam who came to Serbia for employment in the industry and construction sectors in recent years, there are no official reports on these alleged developments, with the Labor Inspectorate remaining silent. One of the most exemplary cases of labor malpractices, which included immigrant laborers, was based on anecdotal evidence and without further court proceedings. It was 2021 when immigrant laborers from Vietnam came to Zrenjanin, Serbia, to construct a factory “Linglong”, led by Chinese in Serbia. The living conditions they were provided with by their employers, which were obligated to do this, were rather bad: accommodation, in barracks next to the construction site, was extremely poor, without warm water and the food they were given was low in calories. Laborers claimed to be satisfied with the salaries, but were unable to send any remittances because their passports were taken away from them. They were not aware that their labor rights were violated, among other reasons, due to the fact that the labor contracts were not written in a language they were able to understand. Elements of the labor contracts, as provided by the national regulations, such as the records on the date of the employment beginning, daily and weekly working hours and holidays, were omitted. They were prohibited from organizing into unions, etc. (A11 & Astra 2022).

Contrary to such malpractices, there are anecdotal records of examples of asylum seekers, especially young and female, employed with the social enterprises, primarily in the sectors of food processing and catering, as well as restaurants. They are frequently included in different types of training in order to be able to perform their activities.

Further considerations

The characteristic of the national labor market is precarious employment, characterized by low salaries, open-ended contracts and low security of jobs. In terms of the attractiveness of the national labor market, therefore, there are low incentives for the immigrants to employ and to stay longer in Serbia. Rather, they will be prone to be employed for certain shorter periods, before being able to transit and to immigrate further, to higher income countries throughout Europe.

These circumstances make the national migration landscape extremely complex and dynamic. Even though 2023 data on immigration reports the highest numbers of immigrants ever in Serbia, the emigration is far more dramatic than the immigration, even looking into national sources, which traditionally tend to underestimate the numbers of emigrants. The immigration is still in the shadow of emigration that is traditionally framed under “brain drain” and recently increasingly more and additionally under “care drain”. This calls for more sophisticated statistics, policies, strategies and measures to be taken by the Government compared to those currently being in place.

Along with the situation on the labor market, the national legislation regarding the immigrant laborers is not empowering for them. Sadly, data on labor immigration in 2024 are currently not available (until July) and any preliminary estimations of the impact of the regulations which came into force in February 2024 can not be made. Concerns come from the fact that simplified procedures, as provided for by the amended regulations, are not operational and actually serve as distracting immigrants to get employment. Its protective clause ruling that the national laborers will be given priority clearly leaves room for the employment of immigrant laborers only in those occupations and sectors that are absent from the national labor market, due to emigration.

The majority of employed immigrants from Russia, concentrated in the information sector, however positive development for the national economy does not seem promising. Namely, the past experiences when the foreign citizens were granted tax and contribution evasions and other benefits, tell us the same: the moment the evasions and benefits were lifted, the immigrants left the country. Chinese immigrants, as the second major ethnic group on the labor market, are still within their ethnic labor market, even though there are new arrivals of Chinese immigrants employed by Chinese companies operating in Serbia. On top of that, labor immigrants are more visible on the national labor market, since they work as bus drivers, construction workers, cleaning ladies, etc. With a view to that, it seems that more extensive measures of supporting immigrants to integrate into society are absent and should be taken into due consideration. Labor integration is surely one of the most important aspects of integration, but some other aspects are also important. Building a society which would welcome migrants requires much more cultural sensitivity, changed media and public discourses and more friendly environments for immigrant families.

Bibliography

A11 i ASTRA. 2022. Izveštaj – UsloviživotairadavijetnamskihradnikanagradilištufabrikeLinglong. A11 i ASTRA.

Arandarenko, Mihail, EliraJorgonii Paul Stubbs. 2009. “SocijalniuticajiglobalneekonomskekrizenaZapadni Balkan.” U Socijalnapolitikaikriza, urednikaDrenkeVukovićiMihailaArandarenka. Univerzitet u Beogradu – Fakultetpolitičkihnauka.

Beogradskicentar za ljudskaprava. 2024. Ljudskaprava u Srbiji 2023 – pravo, praksaimeđunarodnistandardiljudskihprava. Beogradskicentar za ljudskaprava.

Daffini, Ludovica. 2025. A Place to Call Home? Addressing Foreign Nationals’ Challenges to Entering, Residing and Working in Serbia, Available from: https://cep.org.rs/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/A-Place-to-Call-Home.pdf, Accessed on May 19, 2025

European Commission. 2024. Serbia 2024 Report. Available from: https://enlargement.ec.europa.eu/document/download/3c8c2d7f-bff7-44eb-b868-414730cc5902_en?filename=Serbia%20Report%202024.pdf, Accessed on May 19, 2025

https://www.paragraf.rs/propisi/uredba-o-kriterijumima-za-dodelu-podsticaja-poslodavcima-koji-zaposljavaju-novonastanjena-lica-u.html, Accessed on May 19, 2025

https://www.paragraf.rs/propisi/zakon_o_zaposljavanju_stranaca.html, Accessed on May 19, 2025

IDEAS. 2024. Improving Access to the Labor Market for Refugees and Asylum Seekers: Key Amendments to the Law on employment of Foreigners. https://ideje.rs/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/clank_1_ENG-3.pdf

Inspektorat za rad. 2020. Izveštaj o raduInspektorata za rad za 2019. godinu. Ministarstvo za rad, zapošljavanje, boračkaisocijalnapitanja.

Inspektorat za rad. 2021. Izveštaj o raduInspektorata za rad za 2020. godinu. Ministarstvo za rad, zapošljavanje, boračka i socijalnapitanja.

Inspektorat za rad. 2022. Izveštaj o raduInspektorata za rad za 2021. godinu. Ministarstvo za rad, zapošljavanje, boračkaisocijalnapitanja.

Inspektorat za rad. 2023. Izveštaj o raduInspektorata za rad za 2022. godinu. Ministarstvo za rad, zapošljavanje, boračkaisocijalnapitanja.

Inspektorat za rad. 2024. Izveštaj o raduInspektorata za rad za 2023. godinu. Ministarstvo za rad, zapošljavanje, boračkaisocijalnapitanja.

Inspektorat za rad. 2025. Izveštaj o raduInspektorata za rad za 2024. godinu. Ministarstvo za rad, zapošljavanje, boračkaisocijalnapitanja.

Komesarijat za izbegliceimigracije. 2020. MigracioniprofilRepublikeSrbije za 2019. godinu. https://kirs.gov.rs/media/uploads/Migracije/Publikacije/Migracioni_profil_Republike_Srbi.%20godinu.pdf

Komesarijat za izbegliceimigracije. 2021. MigracioniprofilRepublikeSrbije za 2020. godinu. https://kirs.gov.rs/media/uploads/Migracioni%20profil%20Republike%20Srbije%202020%20FINAL%20(1).pdf

Komesarijat za izbegliceimigracije. 2022. MigracioniprofilRepublikeSrbije za 2021. godinu. https://kirs.gov.rs/media/uploads/Migracije/Publikacije/Migracioni%20profil%20Republike%20Srbije%20za%202021-%20godinu.pdf

Komesarijat za izbegliceimigracije. 2023. MigracioniprofilRepublikeSrbije za 2022. godinu. https://kirs.gov.rs/media/uploads/Миграциони%20профил%20Републике%20Србије%20за%202022-годину.pdf

Komesarijat za izbegliceimigracije. 2024. MigracioniprofilRepublikeSrbije za 2023. godinu. https://kirs.gov.rs/media/uploads/1Migracioni%20profil.pdf

Langović, Milica, Danica Djurkin, Filip Krstić et al. 2024. “Return Migration and Reintegration in Serbia: Are All Returnees the Same?”. Sustainability 16 (12): 5118.

Marković, Violeta, “Karakteristikedečjegradakodnepraćeneirazdvojenedece u Srbiji,” PhD diss., (Univerzitet u Beogradu, 2024).

Medić, Pavle, Dragan Aleksić and Vladimir Petronijević. 2022. Analizapotrebatržištaradairadnesnage u kontekstuupravljanjamigracijama. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit. https://ceves.org.rs/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Analiza-potreba-trzista-rada-i-radne-snage-u-kontekstu-upravljanja-migracijama_SR.pdf

Mirkovic, Milika. 2023.Performance of Western Balkan economies regarding the European Pillar of Social Rights 2022 REVIEW ON MONTENEGRO. Regional Cooperation Council.

Nikoloski, Dimitar. 2023. Performance of Western Balkan economies regarding the European Pillar of Social Rights 2022 REVIEW ON NORTH MACEDONIA. Regional Cooperation Council.

Perisic Natalija. 2023. Performance of Western Balkan economies regarding the European Pillar of Social Rights 2022 REVIEW ON SERBIA .Regional Cooperation Council.

Perišić, Natalija. 2016. Socijalnasigurnost – pojmoviiprogrami. Univerzitet u Beogradu – Fakultetpolitičkihnauka.

Republičkizavod za statistiku. 2015. Anketa o radnojsnazi – IV kvartal 2015. Republičkizavod za statistiku.

Republičkizavod za statistiku. 2025. Anketa o radnojsnazi – IV kvartal 2024. Republičkizavod za statistiku.

Republičkizavod za statistiku. 2025. Imigracijastranaca u RepubliciSrbiji. IOM. Srbija. https://publikacije.stat.gov.rs/G2025/Pdf/G202522001.pdf

Sarajlic, Amir. 2023. Performance of Western Balkan economies regarding the European Pillar of Social Rights 2022 REVIEW ON BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA. Regional Cooperation Council.

The LaborLaw, Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia, numbers 24/2005, 61/2005, 54/2009, 32/2013, 75/2014, 13/2017 – decision of the CC, 113/2017 and 95/2018 – authentic interpretation, Available from: https://www.paragraf.rs/propisi/zakon_o_radu.html, Accessed on May 19, 2025

The Law on Employment of Foreigners, Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia, numbers 128/2014, 113/2017, 50/2018, 31/2019 and 62/2023, Available from:

The Law on Social Entrepreneurship, Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia, number 14/2022, Available from: https://www.paragraf.rs/propisi/zakon-o-socijalnom-preduzetnistvu.html, Accessed on May 19, 2025

The Regulation on Criteria for Incentives to Employers Employing Newly Inhabited Persons, Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia, numbers 67/2022 and 71/2023, Available from:

Urdarević, Bojan, Jovana Misailović. 2025. Izveštaj o stanjuradnihprava u RepubliciSrbiji u 2024. FondacijaCentar za demokratiju.

Vuković, Drenka, Natalija Perišić. 2011. “Social Security Transition in Serbia – Twenty Years Later” In Welfare States in Transition – 20 Years after the Yugoslav Welfare Model edited by Maria Stambolieva and Stephan Dehnert. Friedrich Ebert Stiftung.

Ymeri, Sabina. 2023. Performance of Western Balkan economies regarding the European Pillar of Social Rights 2022 REVIEW ON ALBANIA. Regional Cooperation Council.

Zylfijaj, Kujtim. 2023. Performance of Western Balkan economies regarding the European Pillar of Social Rights 2022 REVIEW ON KOSOVO*. Regional Cooperation Council.

Short biographies of the authors

Natalija Perišić is a Full Professor of Social Policy at the University of Belgrade – Faculty of Political Science, Department of Social Policy and Social Work where she lectures on the national and European social policy, ageing and migration at the under-graduate, master and PhD studies. She is a Visiting Professor at the University of Tuzla – Faculty of Philosophy, B&H. Her scientific and research interests in the migration field are within the nexus between migration and welfare state, services for migrants provided by the public and civil sectors, migrants’ integration policies, etc. She has been particularly interested in the mechanisms for social inclusion of migrants. Natalija has been very active in making connections among the academia, civil sector organizations and public services, regarding the support to migrants. She has published about 50 papers in national and international journal. She leads the MIGREC – Migration, Integration and Governance Research Centre at the Faculty of Political Science (www.migrec.fpn.bg.ac.rs).

Violeta Markovic is an Assistant Professor at the University of Belgrade – Faculty of Political Science, Department of Social Policy and Social Work, where she teaches in the field of theory and methodology of social work, with a focus on child protection, people in migration, social work with families,and elderly care. She has5 years in conducting national and international research and participation in national and international projects, with a special focus on developing and conducting qualitative research, from methodology development to data collection and data analysis. She has spent7 years in direct work with people with disabilities, women victims of abuse, and people in migration (5 years). She has extensive knowledge in the area of migration, child protection, family support, Roma people, and social work in crisis. She has published 15 papers in international and national journals and co-authored a book on the protection of children in migration.

[1] The effectuation of the regulations regarding the employment of the EU nationals is postponed and conditioned by Serbia’s membership in the EU.