Elidor Mëhilli

World War II has never really ended in Albania. — Harrison Salisbury (1957)

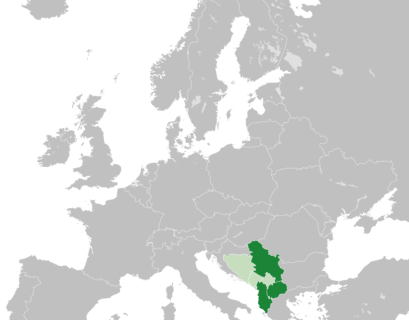

Albania’s ruling Communist party was a product of war—against fascism, following the country’s occupation by Italian troops in 1939, but also of a war waged within the party’s ranks. This latter struggle outlived the country’s liberation from Nazi Germany in late 1944. Over the years, as political alliances with Yugoslavia, the Soviet Union, and China rose and fell, the ranks of so-called enemies of the state also periodically swelled. Making enemies served domestic uses, but relations with the outside world became enmeshed in local struggles. Geopolitical insecurity in the Balkans, in turn, fueled even more conspiratorial thinking, which outlived the alliances with the foreign powers. Throughout these ups and downs, party operatives grew to appreciate the importance of maintaining ties to foreigners. At the same time, they learned the hard way that breakdowns in alliances came with a price. To consider the party’s wartime origins and development against this broader regional and international background is to come to terms with how secrecy became a way of life, how conspiratorial thinking turned into an enforced routine, and how personal loyalties became imperative as the broader socialist world fractured. It also offers an opportunity for histories of Albania to be finally deprovincialized.

For too long, in fact, the writing of modern Albanian history has relied on ideas of exceptionalism. The Communist regime underscored its exceptionalism—every geopolitical break with larger states was cast as proof of ideological purity. Albania was said to have charted its own path. Official history was circumscribed. The study of World War II was highly disciplined. As a result, comparative or international approaches to the war, as well as the postwar period, remain underdeveloped to this day. It does not help that professional historical training lags behind. In the last thirty years or so, much attention has gone to the study of state violence. Such has been the pursuit of the Institute for the Study of the Crimes and Consequences of Communism (Instituti i Studimeve për Krimet dhe Pasojat e Komunizmit), which has issued numerous publications, focusing chiefly on political prisoners, internment camps, biographical data, and testimonies.

Much of the rest of Albanian-language historical scholarship on this period has also been domestic-oriented in scope. The country’s flagship professional journal (Studime historike) first appeared in the 1960s.[1] It continues to be published by the Institute of History, a state-funded entity. In recent years, it has churned out occasionally valuable, if typically narrowly conceived, research on the post-Second World War era. But one problem with Studime is the fact that it covers all periods of historical inquiry—one recent issue included articles on Christianity before and after the Edict of Milan (313 AD), 18-century waqfiya (Ottoman-era foundation deeds) in the city of Berat, and great power involvement in the Balkans in 1914. This means that any one issue might have nothing at all on World War II or the post-1945 period.

In the absence of another professional journal dedicated exclusively to contemporary history, more innovative scholarship on the Communist period has appeared in the multi-disciplinary journal Përpjekja, started in 1994 by Fatos Lubonja, one of the country’s foremost public intellectuals. Përpjekja is unencumbered by the rigidities that have often characterized the Institute of History or the faculties of the state university. And so Përpjekja has been successful in attracting younger authors who are also able to work in various foreign languages. The journal produces thematic issues, which give readers a better sense of the intellectual contours of the published work. Finally, it is also the rare venue where Albanian and foreign scholars publish alongside one another, which has had the effect of making Studime seem all the more parochial and outdated.

Much of the Albanian-language secondary literature consists of general overviews, with a sharp focus on political history. Unsurprisingly, the National Liberation War (Lufta Nacional-Çlirimtare) continues to be a central topic in historical debates. It is in wartime dynamics, after all, that historians have sought the roots of the Communist regime. But as important as the war is, longstanding questions in Albanian-language historiography seem to have turned into dead ends. For example, authors continue to approach archives for clues into the vexing nationalism question: Was long-serving party boss Enver Hoxha a nationalist, or not? Did his rejection of bigger states like Yugoslavia and, later on, the Soviet Union signal an enduring nationalism that supposedly trumped his ideology? Was he, instead, an opportunist? (As if these things had to be mutually exclusive.) Depending on one’s position on these questions, the problem of Kosovo’s fate under Yugoslavia can serve as ammunition to prove either viewpoint. Showing Hoxha to have been “anti-national” (anti-kombëtar) has been understood to go some way towards exposing Communism as alien to the nation’s destiny, which contemporary authors have been at pains to define as “European.”[2]

Historians have thus pursued tedious polemics on whether the National Liberation War could also be thought of as a civil war, such that foreigners (and their domestic stooges) might be shown to have “corrupted” nationalist causes under the guise of internationalism (which is imagined as a “fig leaf” covering nefarious geopolitical plans in Southeastern Europe). Such exchanges have shown a poor understanding of how the literature on the Second World War has evolved outside the country. They have revealed an uncritical attitude towards archives, as if the answers to such questions might derive from newly discovered sheets of paper in a basement. In fact, these are problems of historical interpretation and, above all, imagination. Wartime archives continue to be places of controversy because that is where the political stakes are. Whereas socialist-era historians spent decades crafting a heroic narrative around the war, the effort to expose the war as a form of national betrayal is seen as a way of “delegitimizing” the Communist regime. By comparison, postwar-era state archives are far less explored, though there has been some progress.[3] The outcome has been a remarkably thin archive-based literature that combines a view of politics with everyday life, or that considers the longer-term exercise of state power through the development of institutions, practices, and worldviews.[4]

There is also far too little engagement with scholars of World War II and postwar Communism outside Albania.[5] To internationalize the study of World War II in this area of the European continent, as I see it, means to go beyond merely bringing in British or American sources to the study of the same old questions. It means to engage analytically with international scholarship. Consider the influential work of the Polish-American author Jan Gross, who called for expanding the horizon on Communist regimes by reconsidering the Second World War as a “social revolution.”[6] Gross argued that Communist authorities exploited the opportunities created by wartime upheaval to assert a specific kind of authority, crucially defined on the basis of denying the possibility of any alternative vision to their real and imagined rivals. This simple but essential insight helps us understand regimes that seem at once all-powerful and remarkably vulnerable.

The war incidentally provided an opening for bringing Albania into the international system. It enabled a small militant organization to use war-like tactics to foment social revolution. There were political opportunities for those cunning enough to seize them. But the interplay of domestic dynamics and regional competition in the Balkans also made these years dangerous. Party officials tried to use external actors (British, Yugoslav, Soviet) as leverage or instruments against adversaries. External pressures, on the other hand, further intensified a predisposition towards militancy and conspiratorial thinking.

Local history textbooks later marked the year 1945 as a kind of “zero hour.” The liberation of the country from fascism became inseparable from the Communist cause. If anything, however, 1945 seems like a middle point. In terms of encounters with foreigners and their planning schemes, state designs, and forced and unforced exchanges of people, the 1940s were years of remarkable continuity. Episodes of forced exchange became routine. People made sense of alliances, property reallocations, and acts of violence on the basis of previous encounters with foreign troops and their plans. The memorialization of the war was immediate: Authorities calculated that some 28,000 men and women had fallen as martyrs (dëshmorë) during the fighting. The number remains disputed. War became a story, which is to say that it has invited revision ever since.

“Every aspect of Albanian civilization,” Bernd Fischer has written, “was measured by the wartime experience.” War brought ordinary Albanians into close and violent contact with “foreigners, their ideas, and their guns.”[7] In a continent where powerful states disappeared from the map overnight, a tiny country’s future was never guaranteed. So insecurity produced a great deal of nationalist talk. But it would be wrong to interpret this kind of insecurity as ideological ambiguity. The Communists, after all, seemed to be the only ones with an answer. They inherited, by default, the political support of the Yugoslavs—“specialists of secretiveness, conspiracy, and subversion,” as François Fejtő once put it—which ensured technical aid for building institutions and infrastructure.[8] Even more crucially, the Albanian Communists found themselves on the winning side of the reordering of Europe after Hitler. In From Stalin to Mao, I argued that internationalizing this history helps us raise new analytical questions as well as place Albanian history in conversation with a wider range of scholars around the world.[9]

1. An Expanded View of the War: 1941-1948

For an inexperienced party, Yugoslav backing seemed essential in the 1940s, although Belgrade would later exaggerate its role and the Albanian party leadership—embarrassed by its Yugoslav ties once bilateral relations had soured—would vehemently deny it. After 1944, several Yugoslav advisers did help to shape the party’s structure and they also become involved with economic planning. The two countries signed a friendship and mutual assistance treaty and a customs agreement. Belgrade agreed to supply aid in return for Albanian goods. A number of joint companies were set up to cover the construction of railroads, oil, mining, electricity, navigation, and trade. Belgrade also urged closer coordination in currency policy. The path to economic and political integration between the two countries seemed open. Yugoslavia’s leader Josip Broz Tito clearly had the upper hand. Stalin initially approved of Yugoslavia’s “handling” of its smaller and poorer rural neighbor. Albania’s rulers had to go along with the arrangement.[10]

Heading its party was Enver Hoxha (1908-1985), a teacher-turned-activist who spent his student years in France and Belgium, later joining the Communist ranks at home. Hoxha lacked the revolutionary credentials of someone like Mehmet Shehu, an experienced military man who had participated in the Spanish Civil War. His wartime contributions were no match for Shehu’s. Neither was Hoxha widely known in the early 1940s. Still, he lacked neither cunning nor charisma and above all he had political instinct. At delicate moments, he was particularly adept at presenting himself as an arbiter among competing sides. In this way he quickly came to dominate the party’s inner circle, which included members who were intellectually more impressive. How Hoxha was able to do this is illustrated by his maneuvers vis-à-vis Yugoslavia. Understanding the importance of Belgrade’s support, he had agreed to postpone settling the thorny issue of Kosovë/Kosovo and its Albanian population. The idea was that the region’s future would be settled within a postwar international arrangement. Careful not to alienate his Yugoslav counterparts, Hoxha was nevertheless hardly blind to the unequal nature of this relationship.

After the war, he was party secretary but also served as Prime Minister, Minister of Foreign Affairs, Minister of Defense, and Commander in Chief. (He would be forced to relinquish government posts after Stalin’s death, when high-ranking officials in Moscow demanded changes.) The higher echelon of the Central Committee consisted of other former fighters, tested in battle and trusted for their personal loyalty rather than their level of education or ideological literacy. Indeed, the ideological training came after the fact of Communist power. The party’s upper tier was largely unschooled, as was most of the country’s populace. The figures surrounding Hoxha were relatively young and inexperienced in government. They believed that a world-defining war had placed them on the right side of history. But like Hoxha, they cut their teeth in the ups and downs of the relations between Tirana and Belgrade.

As disagreements between Stalin and Tito erupted in full view in 1948, Hoxha saw an opportunity: escape Yugoslav tutelage by declaring loyalty to Moscow. To lose ties to Yugoslavia carried risk. After all, he himself had publicly lauded Josip Broz Tito. Party apparatchiks had lavishly praised their Yugoslav counterparts. But the move also came with advantages. A sense of insecurity in the party, Hoxha came to learn during the crisis, could be productive. The schism with Belgrade, for example, prompted the top party brass to launch a vicious purge in order to “cleanse” party ranks of supposed enemies and saboteurs. The powerful security police chief Koçi Xoxe, formerly a tinsmith, was declared a pro-Yugoslav conspirator and shot in 1949. Yugoslavia and its local henchmen, according to the new party line, were responsible for recent planning failures and heinous crimes. Signed economic arrangements were now evidence of Belgrade’s “colonial” policy vis-à-vis the smaller country.

Hoxha could influence neither how Stalin handled Tito, nor how anti-Yugoslav fervor would envelop the other Communist leaderships in the late 1940s. But he saw—and seized—a rare opportunity to bypass a regional power and establish a direct channel to the man in charge at the Kremlin. Hoxha’s political survival thus drew on the officially sanctioned story of national survival. Throughout the 1950s, propagandists extolled Stalin as the savior of Albania. Over time, as the cult around his own personality grew, Hoxha would take on the mantle of a kind of a savior himself. Finally, the second half of the 1940s shows the endurance of a wartime confrontational mindset—to borrow from the Russian historian Elena Zubkova, who studied the aftermath of 1945 as a way of understanding how social structure and Soviet people’s lives had been changed by war.[11] To study the afterlife of the war into the 1950s-1960s is to appreciate that war is not just military chronology contained in a textbook, but also biography, social history, demographics, planning legacy, memory, and more.

2. Premature Stalinists: 1949-1960

After 1948, the rhetoric of warfare permeated day-to-day affairs within the party as well as outside its ranks. In the shadow of the Greek Civil War, the party mounted a vigorous propaganda effort. Albania stood encircled, it warned. This notion did not refer just to the reality of the “traitorous” Yugoslavs to the north and the “monarcho-fascists” in Greece to the south. The Anglo-American boogeyman, which Hoxha would tirelessly bring up, was not entirely fictitious. One outcome of the Stalin-Tito split was to make Albania seem “detachable” from the Communist sphere. Anglo-American intelligence operatives saw potential for overthrowing the regime in the late 1940s. The plan was to train Albanian exiles and drop them into the country with the goal of fomenting a rebellion. The services also airdropped Albanian-language leaflets lambasting the regime and issued radio messages (including a short-lived “Voice of Free Albania” edition beginning in 1951) urging locals to resist Communist rule. But the operation proved a disaster. Local security forces promptly ambushed the infiltrators. Radio Tirana issued angry on-air tirades against the meddling. The doomed experiment lent potency to the official party line that the country was under siege. Vigilance became a rallying cry; the security of borders an obsession. The security police (Sigurimi) seemed to become omnipresent though its operatives were frequently inept.

It was hard to underestimate the challenge of building socialism in such a country. The regime presided over a largely peasant and illiterate populace. Modernization was therefore not merely necessary; it was at the core of the regime’s sense of its own survival. In 1949, Albania attained membership in the Council for Mutual Economic Aid. Six years later, it was a founding member of the Warsaw Pact—an important security guarantee. But the scope of Soviet assistance during this period was broader than this. Local officials pleaded with their counterparts in Moscow for qualified technical personnel, who were in short supply. To fund the five-year plans for rapid industrialization, Moscow supplied loans, along with machinery and skilled personnel. The Russian language entered local schools and workplaces. Albanian students enrolled in Soviet universities, thanks to state-supplied scholarships. “The relations we established with Albania were not just fraternal,” Soviet party boss Nikita Khrushchev would later write. “After all, fraternal relations are relations on an equal footing. But from the point of view of the aid we supplied, our relations were like an elder brother toward a younger brother.”

No matter how brotherly the bond, Soviet economic advisers could hardly ignore Albania’s poor agricultural performance, its persistent problem of pushing industrialization onto the back of an unskilled labor force. Stalin’s death and the ensuing developments in Soviet policy under Khrushchev reverberated in Tirana too. Efforts to rekindle relations between Moscow and Belgrade deeply offended Hoxha, whose close Politburo circle had been implicated in the anti-Yugoslav purges. Indeed, a handful of upper-level party members questioned the official version of recent events, going so far as to challenge the way the anti-fascist struggle had become a party myth. They took issue with how history textbooks and official propaganda had made Hoxha a dominant wartime figure. Until then, much of the grumbling had been done in private. After 1953, however, it seemed possible to speak up. Considered from Hoxha’s vantage point, such complaints were neither symbolic nor strictly matters of history. Any kind of rapprochement with Belgrade, he deemed, would require a deeper revision of the party’s foundational core. He vehemently resisted the calls for reform.

Then, in February 1956, Khrushchev delivered his famous “secret speech” heaping blame on Stalin for crimes and foreign policy blunders. The speech shocked the delegates present in Moscow as well as the countless others who heard about it after the fact. Emboldened, a number of party officials gathered at a city conference in Tirana in April. There, they took the party leadership to task. Their goal was not to remove Hoxha from power, as later accusations would put it. In fact, the speakers picked up on the theme of the “cult of personality,” which Khrushchev had highlighted, but they adopted the idea to Albania’s party scene. Why was no self-reflection forthcoming in light of the Soviet example? What about the elite privileges that had emerged in Tirana? Some mistakenly assumed that Hoxha might be prone to a softer approach. In fact, he decisively intervened in the proceedings, blaming the reformers as rotten anti-party elements. This crackdown in the second half of 1956 made it potently clear: no such reform would be forthcoming.

The uprising in Hungary that year—and Moscow’s handling of it—further reinforced the party chief’s anxieties that de-Stalinization could turn into self-destruction. But Hoxha downplayed these concerns in public, paying lip service to Moscow’s recommendations. After all, the country was dependent on the Soviets for economic and technical support. Still, there was no rehabilitation of political prisoners. Paranoia about Yugoslav meddling in internal affairs did not disappear. When Khrushchev finally paid a visit to Albania in 1959, there were celebratory visits to Soviet-funded factories and collective farms. Internal discussions, however, betrayed differences on a number of key issues. The Soviet leader tried hard to keep Yugoslavia out of discussions, which infuriated the hosts. On matters of economic planning, the two sides held opposing ideas. Khrushchev thought that Albania might best serve as a specialized agricultural supplier to an economically integrated Eastern bloc. The country was too small to try and develop in many directions at once. His hosts, in contrast, were obsessed with industrialization as a path to economic self-reliance.

Were the Albanian-Soviet divergences a matter of ideology or a power struggle? A better question might be whether it was possible, at this point, to extricate one from the other. Infatuated with the idea of a division of socialist labor within the Eastern bloc, Khrushchev was not impressed by the geopolitical anxieties that animated his Albanian counterparts. He was unmoved by their old-fashioned obsession with the enemies who surrounded them. For Hoxha, on the other hand, building socialism had become inseparable from Albania’s geopolitical security in the Balkans. Industrialization and military installations were not mere policy options but matters of survival. As relations between Moscow and Beijing worsened in 1960, Hoxha initially tried to keep a distance. He insisted that the two larger Communist parties settle their disagreements on their own. As party representatives gathered in Bucharest in June 1960, Khrushchev and his colleagues tried to bring the disgruntled Chinese under control. Hoxha’s political instincts kicked in once more. He skipped the meeting, where the Sino-Soviet disputes would inevitably come up, sending instead his ally Hysni Kapo. As the Soviets worked to discipline the Chinese, they also tried to get the Albanians to fall in line.

Hoxha stalled. He signaled sympathy for the Chinese position but also kept insisting on the importance of the Soviet Union and the need for resolving disputes through proper tactics. For their part, Chinese party functionaries were pleased that Albania seemed sympathetic to their criticisms. Mao deemed that de-Stalinization had been a mistake. China’s anti-Yugoslav (and anti-revisionist) rhetoric, moreover, had received a warm welcome in Tirana. The harder the Soviet side pushed, the angrier Hoxha’s response grew. Earlier resentment with Soviet tactics on a range of issues now resurfaced more publicly. At a party plenum convened in July, Hoxha catalogued the “mistakes” made by leading Soviet officials going back to Stalin’s death. After consultations with the Chinese later that year, the Albanian delegation denounced the Soviet leadership at the November international meeting of Communist parties in Moscow. The hosts set up a meeting with the Albanians, urging them to reconsider. It was in vain. The meeting ended with the visitors storming out in anger.

A parallel can be drawn between these events in the summer and fall of 1960 and the lessons learned back in 1948. As he had done then, Hoxha strived to turn insecurity into an advantage. Abrupt foreign policy moves could be disorienting. But they were also opportunities to mobilize party ranks in the name of vigilance. The very fact that the party itself had vigorously promoted the Soviet Union made accusations of reformism all the more vicious. Moscow’s attacks against the Chinese, Hoxha told his colleagues, would have disastrous consequences similar to those of the secret speech. In the meantime, Beijing supplied much-needed wheat and promised more technical support. By 1961, Albanian and Soviet disagreements spilled over into military, economic, and diplomatic relations. The two sides rowed over the Soviet-manned submarines stationed in the southern city of Vlorë. Attempts to normalize relations were rebuffed. In retaliation, Moscow withdrew the Soviet ambassador. Khrushchev delivered an angry attack against Tirana at the Soviet party congress in October. In response, Hoxha famously declared that his compatriots would “eat grass” if it came to it, but they would not “sell themselves for thirty pieces of silver.”

In perspective, the 1960s Sino-Soviet-Albanian dynamics show that socialism had worked well enough to create transnational affinities. It had generated a shared language among people inhabiting distant parts of the globe, who used that shared language to describe realities far removed from their own. This was no small thing. But socialism had not yet provided a formula for defeating postwar capitalism and it had not provided an enduring way to handle foreign affairs. Without Soviet subsidies and hardware, building Albania’s socialism would have been a steep challenge. China’s own interests and Mao’s reservations, on the other hand, created some unexpected room for maneuver. These were external factors that Hoxha could not control. His cunning instinct was to try and exploit them, to make international disarray politically useful. The schism shows how strongmen strive by infusing global developments with local meaning. They describe their own struggles in the language of a world-spanning conflict between good and evil.

3. The Uses of China: 1960-1976

The loss of Soviet credits and personnel was a serious problem for the economy’s immediate planning. So Tirana turned to Beijing for support. Over the years, the requests ranged from specialized factories to weapons, gear, and military installations. At times, the bloated requests irritated Chinese government officials. The Chinese premier Zhou Enlai, who visited Albania three times between 1963 and 1966, complained about them. Nevertheless, Beijing went along with the requests, occasionally opting to satisfy Albanian demands by purchasing supplies in the West. Unequal as it was, the relationship also carried symbolic significance. Albania served as an advocate for China’s membership in the United Nations. Moscow, in turn, initially attacked the top leadership in Tirana as an indirect way of criticizing the Chinese.

Throughout the 1960s, a number of high-ranking Chinese officials made the trip to Albania. These included Politburo member Kang Sheng, deputy premier Li Xiannian, and leading Cultural Revolution activist Yao Wenyuan. After the Soviet-led invasion of Prague in 1968, as panic set in about a possible military confrontation, the Chinese sent a delegation headed by Chief of the General Staff of the People’s Liberation Army Huang Yongsheng. At the height of Mao’s Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (1966–70), moreover, Chinese workers, engineers, scientists, athletes, agricultural specialists, women activists, and youths made choreographed visits to Tirana. From the outside, such exchanges and profuse professions of admiration made the Sino-Albanian bond seemed strong.

Looking deeper, however, it becomes clear that the relations were constantly tested both at the party and government levels. Hoxha was initially nervous about the Cultural Revolution’s destructive potential in China. With little information forthcoming initially, he panicked that Mao’s rule might be in jeopardy. All the frenzied talk of revolutionary action was shared between the two sides. But was Mao going too far? It took strong reassurances from Beijing to make Hoxha throw his support behind the campaign. At the same time, he was careful to portray the events in China as necessitated by distinct local circumstances. The upshot was that one could not generalize from the Chinese context into the Albanian one. In 1967, as Albanian delegations were invited to witness the revolutionary upheaval firsthand, officials in Tirana spoke enthusiastically of the struggle for the soul of China’s future. In his later accounts, published after relations with Beijing had soured, Hoxha painted a favorable picture of this period. Since his books were translated into foreign languages, the manipulations took on a transnational life of their own. They have perpetuated the myth that Hoxha had maintained a standing against Mao all along.

It is true that reservations about China predated the Cultural Revolution. In the early 1960s, for example, Hoxha had warned his close colleagues not to exaggerate Mao’s global significance. The possibility of improved Sino-Soviet relations back then had also left him cold. Public pronouncements spoke of rock-solid unity between the two far-flung countries. Internally, however, the Politburo discussions were about being cautious. While Mao’s publications were eventually translated into Albanian, state-enforced propaganda for the Chairman was kept in check. Then, as the Cultural Revolution peaked in 1967, propagandists disseminated Mao’s translated quotations. Hoxha embraced the Red Guards in Tirana, showering them with praise. Still, higher-ups were careful to portray Mao as one political thinker among many and certainly not the greatest.

Albania’s party apparatus launched its own revolutionary campaign in early 1967, designed to look like a spontaneous bottom-up effort aimed at revitalizing party discipline and rooting out bureaucracy and bourgeois practices. Erroneously, Western observers assumed (and some still continue to claim) that Albania copied Mao’s Cultural Revolution. This sees the Balkan country as a perennial client state. In fact, anti-bureaucracy talk was not new in Albania; party higher-ups had spoken about it for years. Hoxha saw an opportunity in 1967 to escalate this “uninterrupted revolution.” And though Albania’s revolutionary campaign coincided with the Chinese, it was crucially different in scope. The movement involved attacks against customs and norms deemed to impede a socialist way of life. Administrators shuttled to the countryside to learn from the masses and to engage in physical labor. Places of worship came under vicious attack, as churches and mosques were sacked, destroyed, or converted into warehouses. But this was hardly designed as an attack against the party apparatus. Indeed, the party was thoroughly in control of the process. Mao’s gamble was thus read as a warning. China also served as a counter-example.

Hoxha’s later memoirs ridiculed Mao’s personality cult, but by the late 1960s his own personality cult was growing. His citations (like Mao’s) appeared on the title pages of academic books, on building façades, and on gold-trimmed red banners in workplaces. In 1968, a specialized party section began collecting and publishing his speeches, articles, and wide-ranging directives on subjects ranging from party discipline and agriculture to aesthetics and music. Seventy-one volumes were put out until 1990. The maroon-covered Works became a common feature of daily life in the 1970s and 1980s. At the same time, speeches at congresses and party gatherings were sprinkled with references to Albania’s push for “self-reliance” (mbështetje në forcat tona). Against the “blockade” that had been imposed by the Soviet Union and the other “revisionist” countries, Albanians were repeatedly told, the country had to learn to stand on its own.

Within a few years, there were signs of a shifting Chinese foreign policy. Suggestions from Chinese top officials that Tirana might rethink relations with Yugoslavia produced displeasure. Chinese overtures towards Romania were similarly unwelcome. The meeting between Soviet premier Aleksei Kosygin and Zhou Enlai in September 1969 was disconcerting. Finally, Kissinger’s visit to Beijing and the news of a planned visit by Richard Nixon, were hard blows. This was taken as definitive confirmation that Beijing had moved away from its ideological resolve. The Chinese premier rushed to Hanoi and Pyongyang to brief local officials on the rationale behind Nixon’s visit. But the Vietnamese appeared unconvinced, and so did the Albanian higher-ups. Zhou tried to convince the Albanian ambassador that Nixon’s trip was an “escalation” of earlier meetings. But he could not downplay its significance, much as he tried. “Of course, Nixon is not coming as a tourist,” Zhou offered. “What would be the point of that?”

In a tense Politburo meeting in August 1971, Hoxha warned that the Chinese aimed to become the world’s third superpower. In this “game of big alliances,” he warned his colleagues, Albania might fall through the cracks. “The time will come when we will be in conflict with the Chinese,” he went on, “unless they backtrack from this path that they have taken. We did not change course. They did.” There was concern that if the Albanians voiced their opposition, Beijing might curtail or even cut assistance. Hoxha and his colleagues thus weighed the options. The Chinese had lavishly praised Albania so the thinking was that they might be reluctant to cut everything off immediately. Still, Hoxha urged vigilance within party ranks because news of Nixon’s visit might cause, as he put it, “some people to waver.” The near future might call for more sacrifices. Albanians “had experience with these situations,” he explained, “so these events should not find us unarmed.” A few days later, the party boss signed a long letter to Beijing detailing all the reasons why bringing Nixon to China was a mistake.

The irony of Sino-Albanian relations was that both sides had worked hard to sustain the myth of deep friendship, only then to find themselves in the awkward position of having to explain Nixon in China. In Tirana, a Central Committee letter instructed local party chiefs to be careful “not to go into too much detail” when talking about Nixon in China. Administrators, managers, and party members were not to discuss it at all with their Chinese counterparts. A few years earlier, as the Cultural Revolution was raging, Chinese officials had asked their Albanian counterparts to criticize them for their ideological errors. In 1971, Tirana did indeed take Beijing to task on account of Nixon, with the consequence of infuriating the Chinese. After the letter, Beijing explained that it would not send a delegation to an upcoming Albanian party congress. In a tense discussion, premier Mehmet Shehu called the act “despicable, brutal, contemptuous—the posturing of a big state against a small one.”

At such key moments, Hoxha took care to appear assured and steady. Other Politburo members raged as they vigorously criticized the Chinese. He urged caution. A discussion about world politics was also a performance of power within a small Balkan political circle. Back in the 1940s, the Albanians had been upstarts. By the 1970s, however, they could claim to have sparred with Stalin, Tito, Khrushchev, and now Mao Zedong. The Chinese, Hoxha explained, were moving away from the ethos of the Cultural Revolution. At the same time, he referred to “good currents” in China, which left a future possibility for a reversal. In the meantime, local propaganda for Mao would be pared down. “The interests of our country and the international communist movement,” Hoxha explained, “require that we do not break with China, even though it is clear to us who we are dealing with.” Continuing to squeeze Beijing as much as possible was not hypocritical, he reasoned. Socialism required it.

Even the applause at the upcoming party congress had to be proper and measured: not too much applause for Mao and China, but no dead silence either. Delegates would receive “signals” about when to applaud. They were to show enthusiasm when China was mentioned in speeches – but not too much enthusiasm.

4. The Price of Self-Reliance: 1976-1990

The 1970s were marked by a series of internal purges. These attacks came in waves, targeting specific sectors: arts and culture, the army, and economic planning. A speech by Hoxha railing against “foreign influences” in 1973, for example, would be followed by top-down investigations against “liberalism” in music, novels, and architecture. References to supposed saboteurs in the army and in planning would be followed by frenzied “party work” to identify culprits. Arrests and internment followed, as did the execution of high-level officials. The long-serving Minister of Defense Beqir Balluku was arrested in 1974 on fabricated charges of organizing a coup and sentenced to death. This was followed by the arrest of the Chairman of the State Planning Commission, Abdyl Këllezi, the Trade Minister Kiço Ngjela, and the Minister of Industries and Mining Koço Theodhosi. Punishment was not exclusively an individual affair; the accused’s immediate family and relatives would also suffer.

In 1976, the country got a new constitution, which enshrined Marxist-Leninism as official ideology. The document forbade credits from or concessions to foreign companies of “capitalist, bourgeois and revisionist states.” This had the effect of enshrining an autarkic mentality that had developed over time. As a result, unlike other Eastern bloc states, Albania did not rush into foreign borrowing to mask its economic problems. Instead, the regime tightened people’s belts and demanded grueling savings campaigns under the much-touted banner of “self-reliance.” Chinese generosity had provided hydroelectric plants, copper- and iron-smelting plants, oil refineries, textile mills, and more. And while Sino-Albanian relations were not severed by Nixon’s visit, they did not survive Mao’s death in 1976 and the ensuing power struggle in Beijing. Even before relations with Chinese had completely broken down, state planners had understood the necessity of making do with internal resources. But the “siege mentality” also proved costly, as resources were funneled into the construction of military tunnels, fortifications, and pillboxes around the country.

In December 1981, Hoxha’s long-time collaborator Mehmet Shehu was found dead in his family villa. The official cause was given as suicide. The event has been a matter of controversy ever since. Shehu had been widely expected to succeed the ailing party chief. He had been unflinchingly loyal for forty years. Shortly after his death, Hoxha declared that Shehu had been a foreign agent all along. After Hoxha’s own death in 1985, Ramiz Alia, a longstanding Central Committee official, assumed leadership. Born in 1925, Alia had initially joined the Communist youth and then the party. He rose through the ranks, becoming a full Politburo member at the time of the Soviet-Albanian crisis. Alia promised to stay the course, but by the late 1980s Albania’s economic catastrophe was evident. Boosting foreign trade had come up before, but how? Forays to West Germany had amounted to little. As agricultural production tumbled, the state went after villagers’ livestock and tiny plots. Crucially, the momentous events of 1989 emboldened youths, especially university students in Tirana. When faced with mass storming of foreign embassies in the capital and mounting pressure throughout 1990, Alia strove to play a difficult balancing act. Soon, the country headed towards chaotic multi-party elections, as thousands of Albanians desperately fled the country.

5. The Endurance of Warlike Thinking

More than forty years of fractures and purges also came with constant revisions to history textbooks. Records had to be “corrected,” party lineages revised, myths maintained. In writing and rewriting the history of the National Liberation War—enforcing the idea of 1945 as a kind of “zero hour”—Albania’s officialdom projected itself as both embattled and internationally relevant. Later geopolitical squabbles with Yugoslavia, the Soviet Union, and China, which I have briefly surveyed in this essay, facilitated the making of this worldview. My point in doing this has been to show that it makes no historical sense—as many in Albania continue to insist—to study the war as detached from the postwar period. As destabilizing as it could be, a history of geopolitical ruptures was also productive for writing narratives of resolve against nefarious enemies. Understanding how dictatorships do this requires sensitivity to the interconnected nature of domestic and foreign politics. From today’s perspective, quarrels within Marxism-Leninism seem hopelessly outdated, even bizarre. In the background, however, were the fears and the hopes of millions of people.

Elidor Mëhilli is Associate Professor of History and Public Policy at City University of New York.

[1] A study of the longer-term development of Studime historike and the historical profession’s role under socialism would be a useful subject to pursue separately. See Marenglen Verli, ‘50-vjet revistë ‘Studime historike’ (1964-2014)’, Studime historike 3-4 (2014): 281-288. The institutional framework for conducting professional historical research is itself a legacy of central planning. The Institute of Studies, started in 1946, had a section on history. It was later renamed Institute of Sciences. When the Academy of Sciences was established in the 1970s, the Institute of History was attached to it. In recent years, the state’s role in organizing research (including the uncertain future of the Academy of Sciences and the formal place of Albanian Studies within public funding schemes) has been a source of contention. A representative example of the Institute of History’s collective effort is Historia e popullit shqiptar: në katër vëllime, 4 vols. (Tirana: Toena/Akademia e Shkencave, 2002-2008).

[2] Many of the so-called polemics have come with select archival documents attached. For example, Ndreçi Plasari and Luan Malltezi, Politikë antikombëtare e Enver Hoxhës: Plenumi i 2-të i KQ të PKSH, Berat, 23-27 nëntor 1944: dokumente (Tirana: Drejtoria e Përgjithshme e Arkivave, 1996). See also Uran Butka, Dritëhije të historisë: (polemikë me Kristo Frashërin) (Tirana: Maluka, 2012); and Lufta civile në Shqipëri: 1943-1945 (Tirana: ISKPK, 2015); Uran Butka, Mukja – shans i bashkimit, peng i tradhtisë (Tirana: Naim Frashëri, 1998). Butka, for example, has taken issue with the work of Kristo Frashëri, who was one of the principal historians of the left in Albania and co-author of some of the country’s textbooks. Among Frashëri’s more recent works, see Historia e qytetërimit shqiptar: nga kohët e lashta deri në fund të Luftës së Dytë Botërore (Tirana: Akademia e Shkencave e Shqipërisë, 2008); Mbi historinë e Ballit Kombëtar: (vështrim kritik) (Tirana: Dudaj, 2012); Kongresi i Përmetit (24-28 maj 1944): vështrim historik dhe burime dokumentare (Tirana: Akademia e Shkencave, 2015); Shqipëria në Konferencën e Paqes, Paris 1946: (vështrim historik) (Tirana: Akademia e Shkencave e Shqipërisë, 2015). For an overview of Frashëri’s role in Albanian historiography, see Michael Schmidt-Neke, ‘Kristo Frashëri (1920-2016)’, Südost-Forschungen, 74, 1 (August 2015): 208-210.

[3] Examples of general 20th century texts include Valentina Duka, Histori e Shqipërisë, 1912-2000 (Tirana: Kristalina, 2007) and Kastriot Dervishi, Historia e Shtetit shqiptar 1912-2005 (Tirana: 55, 2006). Specifically on the postwar period, see Hamit Kaba, Shqipëria në rrjedhën e luftës së ftohtë (studime dhe dokumenta) (Tirana: Botimpex, 2007), and Shqipëria dhe të mëdhenjtë: nga Lufta e Dytë Botërore në Luftën e Ftohtë (Tirana: Klean, 2015). Ana Lalaj’s Pranvera e rrejshme e pesëdhjetegjashtës: vështrim studimor mbi Konferencën e Tiranës dhe dokumente për protagonistët e saj (Tirana: Infbotues, 2015), examines the 1956 challenge of de-Stalinisation by combining attention to domestic pressures with foreign policy imperatives. This is not a comprehensive list of titles—merely a selection.

[4] An exception to this point is recent work on socialist morality and the creation of a “new man.” See, for example, Idrit Idrizi, “Der Neue Mensch in der Politik und Propaganda der Partei der Arbeit Albaniens in den 1960er Jahren,” Südost-Forschungen, 69/70 (2010/2011): 252-283; and Herrschaft und Alltag im albanischen Spätsozialismus (1976-1985) (Berlin: De Gruyter Oldenbourg, 2018).

[5] A welcome recent dissertation shows how Albanian activists pursued objectives within a multinational framework throughout the first half of the century, reinstating Ottoman-era precedents and associations to the history of interwar activism and Communist organization. Lejnar Mitrojorgji, ‘Between Nation and State: Albanian Associations from Ottoman Origins to a Communist Party, 1880-1945’, PhD dissertation, University of Maryland, 2016.

[6] Jan Gross, “The Social Consequences of War: Preliminaries for the Study of the Imposition of Communist Regimes in East Central Europe,” East European Politics and Societies 3:2 (Spring 1989): 198-214.

[7] Bernd J. Fischer, Albania at War, 1939-1945 (West Lafayette, Ind.: Purdue University Press, 1999), p. 3.

[8] François Fejtő, “La deviazione albanese,” Comunità, Nr. 107 (1963): 18-32 (at 19).

[9] Elidor Mëhilli, From Stalin to Mao: Albania and the Socialist World (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2017).

[10] For a recent compelling example of placing the Albanian episode in a comparative framework, see Naimark, Norman, Stalin and the Fate of Europe: The Postwar Struggle for Sovereignty (Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2019.

[11] Elena Zubkova, Russia after the war hopes, illusions, and disappointments, 1945-1957 (London: Routledge, 2015).