NAIM RASHITI

Executive Director

Senior Policy Analyst, Western Balkans and EU

Balkans Policy Research Group

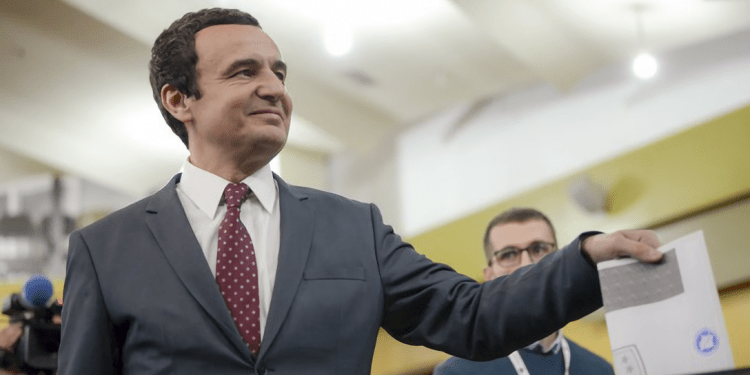

Kosovo held new snap elections on 6 October this year. The record-high turnout brought change in the political landscape. Vetëvendosje Movement (LVV) of Albin Kurti won the elections with 29 out of 120 seats of the Kosovo parliament. Democratic League of Kosovo (LDK) came second with 28 seats. The governing coalition of warriors lost elections. Democratic Party of Kosovo (PDK) of Kadri Veseli came third with 24 seats. The Alliance for the Future of Kosovo (AAK) of Prime Minister Ramush Haradinaj earned only 13 seats. The victory of the opposition parties, VV and LDK

need still work to materialise. Elections results were certified only in late November, almost two months after the vote and the electoral system impose coalitions of large number of parties.

In public, the opposition parties until now, LVV and LDK brought hopes. Voters expect them to change governance, fight corruption, attract investments and stand up against any possible

‘controversial options” for an agreement with Serbia. Kosovo’s context offers

little room for radical improvement; it will be constrained by both the

socio-economic reality, with an inefficient, starved-for-funds state and a

dysfunctional party system, and the need to move forward in the various

international-sponsored processes. All of this, in a difficult political

landscape.

Despite the generally cordial campaign that

preceded the elections, relations between key political actors remain tense;

leaders do not trust each other and basic norms of cooperation between actors

are still missing. That is especially true for the case of Albin Kurti, the

leader of Vetëvendosje, who has spent much of his time in opposition (and

before that, as an activist) attacking other parties, including his current potential

partner LDK.

Last two years, Prime Minister Haradinaj had

tense exchanges with President Hashim Thaçi, and the President of the Assembly,

Kadri Veseli, the leader of PDK, the largest party of the coalition. At some

point, relations between them broke down to a point of refusing to talk one to

another. Vetëvendosje and LDK made a strong largely not-so-loyal opposition to

Haradinaj; should they join forces in power, they will face the same treatment

by the remnants of the PAN coalition. In particular, Haradinaj’s AAK will harshly

defend the tariffs against Serbian goods once Kurti will remove them. In

addition, PDK, which would then be the largest party in opposition, will be a

challenging partner for the new government.

Furthermore, how the new government will

interact with President Thaçi and his office remains doubtful. President Thaçi

has so far exercised a more central role in Kosovar politics than his

predecessors, due to the continuous presence of his former party in the

previous governments. However, in a government led by Vetëvendosje and LDK, his

influence will certainly diminish. In fact, given past animosities with them,

it is likely that conflict will continue, at least until Thaçi’s end of mandate

in 2021. Should the Head of State fail to build a working relationship with the

Head of Government, a number of issues will risk stalling, including Foreign

Affairs and the Dialogue with Serbia. Similarly, various appointments for

independent constitutional institutions require consensus of both and can

become a source of conflict between them. Sustained personal distaste, a shared

history of mistrust and discord, and conflicting egos will make building

constructive relations difficult, if not impossible.

If Kurti were to secure the premiership, he

ought to build some relations with both his coalition partner and the

opposition, with whom he never tried to reconcile. Any new government will have

to create a favourable climate to enact the promised reforms. In the case of

Kurti, especially, would entail making a U- turn and engaging with the

opposition from day one.

First, he has to agree with LDK on a governing

coalition and share of power; both had long engaged in talks and claimed to have

come together to a joint governing program, a structure of the government,

priority policies, dialogue with Serbia etc. Yet all broke down when they set

to negotiate posts. LDK leader wants VV to grant him the post of the country

President in 2021, after the mandate of Hashim Thaci end. For Kurti this is too

much. Even if an agreement between LVV and LDK is reached soon, they ought to

negotiate with minorities, including Serbs to vote their government, whose

position is still unknown.

Kurti chose LDK with whom have considerable differences; LDK is a conservative party that is loyal to the statehood and identity of Kosovo, and fully adhere to liberal policies of economy, governance etc. VV insists on opposite policies. For example. LDK supports full privatisation of socially owned and public enterprises, Vetëvendosje wants to put all companies under a government scheme. LDK’s trust on its potential is very low, and worry that it will be marginalised in the Kurti government or divert policies. It’s a relation that was never tired; often conflicts between them were much higher than with others, in particular when LDK leader Isa Mustafa led the government of Kosovo between 2015 and 2017.

Both, LVV and LDK oppose new compromises in the dialogue with Serbia. For Albin Kurti, dialogue with Belgrade is not a top

priority. EU and U.S. expect the new government to immediately engage in the

dialogue. The Kurti-led government will remove the 100 percent tariffs imposed

on goods coming from Serbia and Bosnia but will impose “full reciprocity” that

will not make any easier for Belgrade. Kosovo’s allies worry that new measures

can delay dialogue and if does not start soon, “the dialogue will pose for much

longer”. U.S. with two envoys, and EU

to-soon-appoint a new special envoy expect Albin Kurti to appoint a broad-based

negotiating team and together with President Hashim Thaçi to soon participate

in the high-level dialogue, i.e. upcoming Paris Summit that French President

Emanuel Macron has long aimed at doing.

LDK is more sensitive than VV toward the demands coming from

international friends of Kosovo.

In recent months Albin Kurti has attempted to

make himself a more Kosovo centric politician. Yet, LDK remains concerned and

worry that Kurti can change position toward Kosovo statehood, its symbols, constitution, territory etc. Led

by Vjosa Osmani, but not only, LDK wants to consolidate ‘Dardania’ identity of

Kosovo, established by the former leader Ibrahim Rugova. This is not one of

Kurti.

Many local and international actors worry that

should Albin Kurti fail to conduct or conclude the dialogue with Serbia, he may

shift to his old agenda, the laisse deep in his hear, a confederation with

Albania. It has become a practice for the leaders of Kosovo and Albania to

promote unification every time they fail at home, but all doubts intentions of

Edi Rama or Hashim Thaçi when they do so. In the case of Albin Kurti is

different; he had long promoted this policy. LDK will oppose any formal rapprochement with

Albania; it will rigidly oppose the debate for any special arrangement, a

confederation or any institutional make between two countries, that undermines

the sole sovereignty of Kosovo.

Likewise, LDK will strongly oppose new regional

initiatives, i.e. min-Schengen that recently leaders of Serbia, North Macedonia

and Albania launched. Kurti objected cautiously, largely aiming at avoiding

public disagreements with Albanian Prime minister Edi Rama. LDK will oppose

Rama too.

Kosovo domestic problems are enormous too.

Yet, the new government can find a much greater leeway to launch its own

initiatives on key reforms, accountability of government, functioning of the institutions,

depolitisation and effectives of highly corrupted independent agencies and

regulatory bodies, foreign policy and attracting investments. It shall

priorities strength of the institutions, fight against the informal economy and

employ competent officials.

Kurti needs to strengthen rule of law and

reforms of judiciary, increase pace on the fight against corruption and organised

crime and lobby to the EU member states to secure

long-delayed free visa travel for Kosovo citizens, no later than second

half of 2020, when Germany preside the council. Low quality Education and a

dysfunctional healthcare are in high demand better policies. Citizens expect

Vetëvendosje and LDK to soon deliver on all those ‘priorities’. Kurti needs

to show rapid change to meet the high expectations, to which he has long

contributed too. The composition of the government, domestic politics and

international developments will determine the success or failure of Albin Kurti

as leader of Kosovo.

*This article is written before the new Kosovo institutions are constituted, and anticipate that Vetëvendosje and LDK will reach an agreement to form a majority and Albin Kurti to lead the government.