ALBERT RAKIPI, PhD

Abstract

The increase in political communication between Albania and Serbia, including initiatives for economic co-operation, as well as heralding a new era in their relations has stimulated a surge in discussion about various themes: the capacity and will of the two states for collaboration; current and future problems in inter-state relations between Albania and Serbia; relations between Albanians and Serbs in the Balkans; the question of reconciliation; and, last but not least, the potential implications of an evolving and deepening Albania-Serbia relationship for inter-state relations between Albania and Kosovo and between Serbia and Kosovo.

Efforts to normalize inter-state relations between Albania and Serbia began immediately after the fall of the Milošević regime, and particularly after the redrawing of the Balkan political map after Kosovo’s independence in 2008. The recognition of Kosovo as an independent state marks an historic step in what, for the past century, had for Albanians represented the core of the national question. Starting in Autumn 2014 Tirana and Belgrade sent clear signals that they wished to inaugurate a new era in their generally conflictual relationship. Over the last five years Albania and Serbia have increased their political communication and undertaken several concrete steps to increase economic co-operation. Although progress has been modest so far, there is every chance of a new phase in relations between the two states. Yet the myth of the centuries-old enmity between Serbs and Albanians in the Balkans, the war in Kosovo with the Milošević regime’s extermination campaign there, and absent or weak economic interdependence, have meant that support on the ground remains limited for the meaningful establishment of a new relationship.

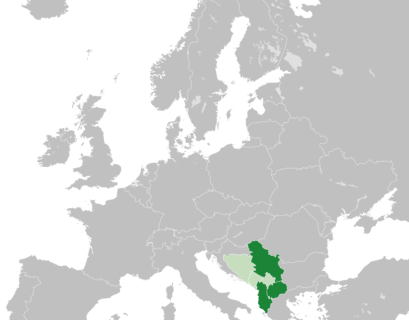

On the geo-political level, Albania and Serbia are two key countries for the western Balkans and beyond, bearing in mind that Albania has been a NATO member since 2009, is a candidate for EU membership, and has supported and continues unreservedly to support EU and more generally western foreign policy including towards the great powers outside the Balkans – above all Russia. At the same time, in the historical context Albania is seen as the mother-country for all those Albanians who, since the foundation of the Albanian state in 1913, have remained outside its borders and are now citizens of other states in the region: Kosovo since 2008, and North Macedonia and Montenegro following their departure from the Yugoslav Federation and establishment as independent states.

Although Albania’s role has diminished, and with Kosovo independence technically Albania can not be the mother-country for Kosovo’s Albanians, the country nonetheless retains strategic importance in the confrontation, competition, co-operation and balance between two peoples, the Albanians and the Serbs, whose relationship historically has been antagonistic, conflictual and often hostile.

On the other hand, with an historically consistent policy focused on dominating the other countries of the region, Serbia continues to refuse to recognize Kosovo’s independence, sustaining a frozen conflict between them, something that does nothing to improve relations between Albania and Serbia and indeed makes difficult, if not impossible, lasting peace between Kosovo and Serbia and in consequence reconciliation between the two peoples.

From a geo-political perspective, Serbia – which represents the largest and most competitive state and market in the region – pursues a policy at first glance open towards both the West and the East, an approach that recalls Yugoslavia’s foreign policy through the Non-Aligned Movement; but at heart, the current policy remains at the very least controversial. Although the first country to have opened EU membership negotiations, and having made significant progress in that process, Serbia has never supported the foreign policy of the EU, the club it wants to join, with regard to other powers – principally Russia. In 2007 the Serbian Parliament declared its neutrality, but in 2015 Serbia signed a NATO Individual Membership Action Plan, following a process of collaboration through the Partnership for Peace with the alliance – which had in 1999 undertaken military operations including airstrikes against the Milošević regime. While preparations continue for the adoption of a new Individual Partnership Plan[1], in parallel Serbia maintains a steady military co-operation with Russia.

In the context of historically inimical relations between Albanians and Serbs in the Balkans, and following the war in Kosovo which led to the country’s independence and a new geo-political arrangement, it is striking that since 2014 Albania and Serbia have strived to open a new chapter in their inter-state relationship.

The following study analyses current inter-state relations between Albania and Serbia, the implications that these might have for their future relationship, the potential consequences of Albania-Serbia relations for the question of reconciliation between Albanians and Serbs in the region, and last but not least the possible effects of this new engagement on state relations between Albania and Kosovo and indeed between Serbia and Kosovo.

CONFLICT AS THE DOMINANT MODE OF RELATIONSHIP

Enmity and hostility have been a dominant theme between Serbs and Albanians, with a persistent Serb effort to predominate, at least as far back as the creation of modern states in the Balkans – the period for which there is a relatively accessible factual record. Historically, Albania’s neighbours have argued, competed and fought over how they might divide the lands of the Albanian people and later the Albanian state, and in 1912 Serbia and Montenegro took the lion’s share, ’40 percent of the Albanian people and more than half of the territory occupied by Albanians’[2]. This was seen as a great injustice, for which Albania blamed the European Great Powers of the time as well as her neighbours. In a manner both paradoxical and tragic, the creation of the Albanian state did not resolve the Albanian national question, which in 1912 represented no more and no less than the collection and unification in one state of all the Albanian territories annexed by others – chiefly what would become Yugoslavia – with the support of the Great Powers. The laying of foundations for a modern Albanian state during the reign of King Zog was accompanied by what at first glance appears a contradictory foreign policy, especially as regards Belgrade, but Zog contrived a masterful Balkan balance in an environment almost entirely hostile towards such a state.[3]

After the end of the Second World War, Albanian-Serb relations developed in the context of the state relationship between Albania and the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. An extraordinary change, almost incredible and unimaginable in the traditional context, was marked immediately and for the first two or three years after the war, with communist Albania and Yugoslavia moving quickly through a number of agreements towards a special alliance.[4] Yugoslavia’s remarkable influence over Enver Hoxha’s communist government was understandable given the role the Yugoslav Communist Party had played in the formation of the Communist Party of Albania. Thus Albania was slipping rapidly and without fuss into the Yugoslav orbit, ready to be transformed into one of the federal republics. With the signing of a treaty of friendship in 1946, Albania and Yugoslavia entered into a political and military alliance which represented, as has been mentioned, a dramatic reversal of the whole foreign policy of the modern Albanian state. This alliance was reinforced by the signing of a treaty for the co-ordination of economic policy, customs co-operation and union of currency, and in 1947 Belgrade presented a plan for the unification of Albania and Yugoslavia on a federal basis. But in 1948, disagreements between the Soviet Union and the Yugoslav Federation also brought an end to the honeymoon between Albania and Yugoslavia.

Relations between Albanians and Serbs, within the framework of state relations between Albania and the Yugoslav Federation, were essentially frozen for more than two decades. But at the end of the sixties there was a new movement between the states, connected to a number of factors related chiefly to the dynamics of the Cold War, including the dramatic episode of Czechoslovakia’s invasion by the Soviet Union and the new alliance between Albania and China. This was the second non-conflictual phase in the period following the Second World War, and it enabled another relatively dynamic co-operation between Albania and Kosovo. At the beginning of the nineties Albania had just emerged from communism, and Milošević’s Yugoslavia was on the brink of a military conflict.

TOWARDS A NEW CHAPTER

Ever since the fall of the Milošević regime Albania has shown herself ready to establish dialogue and co-operation with Serbia. Even before the Serbian President’s fall, during a very tense period in relations between Albanians and Serbs, Albanian Prime Minister Fatos Nano had no hesitation in meeting him at the Crete Summit, in November 1997. The war in Kosovo – the last of the wars of the former Yugoslavia – was about to erupt and it was hard to imagine that the summit, and in particular the meeting between the Albanian Prime Minister and the Serbian President, could manage to prevent a new conflict between Serbs and Albanians in Kosovo, let alone establish a new atmosphere in the regime. Following the Crete Summit Milošević declared that Kosovo was an internal matter for Serbia and that the solution should be found in guaranteeing the fundamental rights of Albanians in Kosovo, not in autonomy.

After the fall of Milošević, political dialogue and relations between Tirana and Belgrade moved onto a more or less normal track, with what was in fact a rather engaged and constructive attitude by the Albanians. Immediately after the re-establishment of diplomatic relations, in January 2001, the two countries committed to increasing contacts. Deputy Prime Minister Ilir Meta visited Belgrade in 2003, and the Foreign Ministers exchanged visits.

Economic relations, though modest because of the prolonged split and lack of communication, stimulated interest in both countries, and a number of agreements were signed. Economic transactions rose from $233,000 in 2000 to $139,000,000 in 2010. From 2006 Albania and Serbia are both members of the Central European Free Trade Agreement (CEFTA), which has had a considerable impact on trade exchanges. After CEFTA accession Serbia became one of Albania’s largest trading partners.[5]

Over the last five years trade and other exchanges have grown, and a number of Serbian companies competing in the Balkans have shown interest in investing in the Albanian market. In 2014 annual economic exchanges passed 173 million euros.[6] Since 2016 there has been an increase in trade activity between the two countries, and in 2018 it reached 181 million euros.[7] In September 2014, Air Serbia began direct flights to Tirana, which brought practical improvement to communication, while statistics showed a growing number of Serb tourists choosing Albania as a destination.[8]

The relatively prolonged isolation between the two societies, the absence of communication including culturally, the undoubted myth of historical enmity between the two peoples particularly over Kosovo, the war there and then independence with substantial western backing, do not make co-operation and integration easy. Not a few Serbs, visiting Tirana and Albania for the first time today, are very surprised to find an open society and a non-hostile atmosphere; on the contrary, tourists find a friendly atmosphere and are made welcome.[9] Their great surprise is connected to the perception they seem to have of Albania and Albanians. The myth of the two historically opposed nations seems to trap in the past a significant portion of Serb society, media and unfortunately those in power. The same myth is apparent in the minds of Albanians, though principally among the diaspora in western countries as well as in North Macedonia and Kosovo.

According to an analysis by the Institute for International Studies, the majority of Albanians think that if there is a state that represents a threat to Albania, it is not Serbia – as many might suppose – but Greece.[10] In their efforts to establish meaningful relations with Serbia, it seems that the Albanian Government have the support of Albanian society too, the majority of whom consider relations with Serbia important.[11]

FROM ENTHUSIASM TO STATUS QUO

In 2014, the restoration of direct flights between Belgrade and Tirana was thought to herald a new phase in relations between Serbia and Albania. Attending the inauguration ceremony for the route, the Albanian Ambassador in Belgrade declared that the Albanian Prime Minister would himself use Air Serbia to travel to Belgrade[12] in a month’s time.[13] Everything suggested a new beginning: nearly 70 years had passed since the first and last visit by an Albanian Prime Minister to Belgrade. The JAT that had carried Enver Hoxha towards the city in 1946 had disappeared. Yugoslavia itself had disappeared too, after Serbia’s violent attempts to dominate the other republics. The political map of the Balkans had changed several times, most recently with the establishment of Kosovo as an independent state. There was great enthusiasm and expectation.[14] The international press spoke of a historic visit and in the same way European diplomats anticipated, wrongly in fact, that stronger relations between Albania and Serbia would automatically mean reconciliation between Albanians and Serbs in the region.[15]

Five years after this enthusiastic beginning, where have relations between Albania and Serbia got to? Unusually in international relations in the Balkans, the trajectory of Albania-Serbia bilateral relations is an example where perceptions are not so far from reality. Today only a third of Albanian citizens judge that relations with Serbia are good (24%) or very good (7%).[16] Albanians have almost the same perception of relations between the two governments.[17] At the same time, there are also perceptions of relations between Albania and Serbia[18] to indicate the trend in these relations and their condition today.

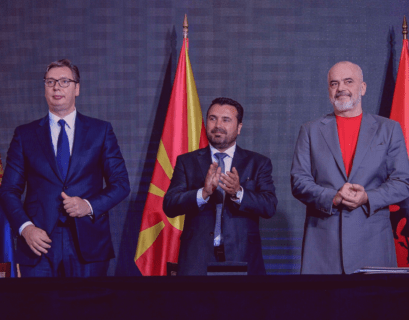

The fact that a majority of 44 percent believe that relations are neither good nor bad[19] suggests that a condition of status quo is a more realistic, meaningful and complete picture of relations today. Over the last four to five years there has been high-level communication and dialogue. The Prime Minister of Albania has visited Belgrade twice, and likewise Aleksandar Vuçiç visited Albania for the first time as Prime Minister and again as President of Serbia. Besides state visits, the countries’ two figureheads have often met under the auspices of the Berlin Process or of various regional initiatives[20], including the most recent Balkan Schengen initiative[21].

But despite bilateral contacts and communication in regional meetings, political relations between Albania and Serbia have not advanced in any substantial manner. In general, the optics of the meetings are excellent, and it seems clear that the two protagonists are taking enormous care that such images, which will be seen not only by their publics but in the global centres of decision-making in Brussels and Washington, should be precisely composed and above all that they transmit the message that Tirana and Belgrade are building new, collaborative and close relations. But behind the beautiful facades and the subtle nuances of staging there is little substance. This reflects the fact that high level meetings and dialogue, in which only the principles and readiness for co-operation are discussed, rarely if ever get down into the operational aspects of co-operation. It is true that economic relations between Albania and Serbia have improved relative to 2014, but after the initial boost in the second half of that year the progress and deepening of those relations has followed an ever-slower rhythm.

There is no doubt that economic relations received a jolt in 2014, also through the enthusiasm and friendly atmosphere that was created. But the vitality of trade between the two states has come to a considerable degree from membership of CEFTA and its instruments. In 2013, trade exchanges between the two countries totalled 103 million euros, and just a year later they reached 173 million. But in 2018, exchanges had only climbed to 181.4 million euros[22], experiencing an increase of 2.9% over that five year trajectory. Meanwhile, Serbian trade with Albania represents only a very small part of its general trade. In 2018, exports to Albania were only 0.8% of Serbia’s total, and imports from Albania only 0.2%. These figures had changed little since 2013: the Albanian element of Serbia’s imports had grown from 0.1% in 2013 to 0.2% in 2018.[23]

Although there is no doubt that economic relations between Albania and Serbia have reached a kind of status quo, a realistic appraisal of economic relations and mutual investment should take into consideration the weak and impoverished tradition of their economic links, leaving aside of course the honeymoon period between Albania and Yugoslavia in the first two years after the Second World War. This becomes clearer in a comparison of trade exchanges between Serbia and Albania with trade exchanges between Serbia and Kosovo[24], which are many times higher despite the fact that the two states do not recognize one another and remain in a frozen conflict. While trade exchanges between Serbia and Albania were 181 million euros in 2018, those between Serbia and Kosovo in 2017 were around 450 million euros, of which 420 million were Serbian exports to Kosovo.[25]

During the past five years several agreements have been signed, such as those for free movement of citizens[26], mutual recognition of driving licences, customs[27], aspects of cultural co-operation, trans-national transportation and tourism. But most of those agreements were signed in 2014, during the visit of the Albanian Prime Minister to Belgrade. Most of them, indeed, are agreements in principle, which are missing the concrete instruments that would deepen the co-operation. The only agreement that is judged to have increased interaction between the two countries appears to be that for free movement of citizens.

In practice, this agreement, signed in 2014, foresees travel by citizens of the two countries with identity card. But it is not clear how an agreement allowing their nationals to travel with identity cards instead of passports can achieve an increase in free movement. Even this agreement, though signed back in November 2014, has never been fully implemented, and five years after its signature Albania and Serbia are re-proposing the measure as part of a new initiative, the so-called Balkan Schengen.[28]

FROM STATUS QUO TO A FALSE STRATEGIC AGENDA

Since 2014, on the agenda of political meetings and dialogue between Albania and Serbia at the highest state and governmental level, issues of bilateral co-operation have been replaced by a more strategic approach, which relates principally to the future of the Western Balkans, peace-building and regional integration. From the first official discussions in November 2014, when the Albanian Prime Minister made his public call in Belgrade for the recognition of Kosovo, this last theme has been included and even predominant in every meeting and public message of Rama with Vuçiç, both ‘forgetting’ – each for his own reasons – that the bilateral agenda includes the business of a third state which neither had nor has the authority to represent. This inclusion ‘by force’ naturally makes the bilateral agenda between Albania and Serbia very political and strategic, and a hot topic for local and international media.

During the second half of 2019, time and space on the strategic agenda of the two countries was devoted to the Balkan Schengen, a controversial initiative based on the model of the EU’s Schengen arrangements, which would make possible and applicable four major freedoms: the movement of people, services, goods and capital among six states of the Western Balkans, three of whom – Serbia, Kosovo and Bosnia – do not recognize one another.[29]

Serbian President Vuçiç and Albanian Prime Minister Rama have begun to promote the Balkan Schengen through three summits, first in Novi Sad, then in Ohrid and finally in Tirana on 21st December 2019. North Macedonia has joined the initiative, while Montenegro and Bosnia have remained more or less reluctant to participate and Kosovo has categorically refused.

A commitment to reconciliation in the Balkans, peace-building, co-operation and regional integration is a billet-doux sent from the region to Brussels or Washington, and certainly welcome at least in so far as it would never be refused. In this way, there is less and less space on the Albania-Serbia bilateral agenda for concrete issues of political co-operation, economic co-operation for trade, investment, tourism, and energy, co-operation in the security sector or co-operation in the fields of education and culture.

In the narrative used domestically, the leaders of Albania and Serbia are careful to articulate the message that the strategic agenda they are now pursuing either, for Albania, has the full support of Brussels and Washington[30], or is happening because the time has come for the countries of the Balkans to take their fate in their own hands, for Serbia[31]. In both cases, today’s political elite in Tirana and Belgrade aim to increase support for their authority, in Albania’s case by buying legitimacy from outside (the European Union and the USA), and in Serbia’s case by striving to stir the public with a nationalist/populist narrative, blaming the intervention of foreign and principally western powers for problems old and new.[32]

The affectation by Albania and Serbia of a strategic agenda, purportedly helping reconciliation and making history[33], is unsustainable and even false, for at least two reasons. Firstly, however the political agenda of Albania-Serbia co-operation might appear from a preliminary strategic glance, the Serbian recognition of Kosovo’s independence that would mark the resolution of the frozen conflict between them, which remains undoubtedly the fundamental issue in inter-state relations in the Balkans, has not been on the agenda – setting aside the Serbian Prime Minister’s long panegyric in Belgrade in November 2014, when he called for Belgrade to recognize Kosovo independence.[34] Secondly, the resolution of this frozen conflict, which should be a sine qua non for the establishment of peace, cannot be something agreed within Albania-Serbia relations.

There can be no doubt that – while not automatically excluding Albania’s potential role in the issue of reconciliation between Albanians and Serbs in the region[35] – reconciliation in fact must involve Serbia and Kosovo.[36]

If, five years after the first burst of enthusiasm and similarly great expectations, relations between Albania and Serbia are ‘suffering’ under the ’tyranny of the status quo’, the fundamental question is: what are the causes and factors obstructing an emergence from this status quo, and then forward movement and the deepening of relations between these two states crucial to stability and regional balance? The answer to this question starts to become clear if we look at of the agreements proposed by Tirana over many years and consistently refused by Belgrade: an agreement in the field of education and the recognition of diplomas. This would be one of the agreements that would automatically bring Kosovo into the relationship between Albania and Serbia: the signing of such an accord and mutual recognition of diplomas between them would mean the recognition of diplomas earned by students from Kosovo, and also students from the Preshevo Valley in southern Serbia, who have studied or are studying in the University of Tirana. But the ‘road’ to the signing of this agreement between Serbia and Albania ‘goes through Prishtina’, in Albin Kurti’s metaphorical description of the importance and conditionality that Kosovo represents for the future of Serbia-Albania relations.[37]

But it is not only the leader of the Vetëvendosja Movement – in all likelihood Kosovo’s next Prime Minister – who insists that Kosovo must also be included in the equation for the future relationship between Albania and Serbia. Albanian citizens identify that one of the chief obstacles for the development and deepening of the relationship, in light of the historical enmity between the peoples, is Serbia’s non-recognition of Kosovo and current policy towards the country.[38]

Those two issues, which are seen as the chief obstacles to the development and strengthening of relations between Albania and Serbia, are at heart to do with Kosovo. Kosovo seems to have been and to remain fundamental and in no small measure decisive for the future of the relationship. A substantial majority – 88 per cent – of Albanian citizens think that Kosovo is important (51%) or very important (37%).[39]

Accordingly, the explanation for the status quo should be sought in fully answering the following questions. Firstly, is – or to what extent is – the development and strengthening of Albania-Serbia relations possible bearing in mind that Serbia not only does not recognize Kosovo but, as has been demonstrated in recent years, accompanies this frozen conflict with aggressive diplomacy aimed at the retraction of international recognitions?[40] Secondly, are Serbia-Albania relations influencing Albania-Kosovo relations, and if so how?

ALBANIA-SERBIA: KOSOVO AS A PROXY WAR

When the Albanian Prime Minister made his first visit to Belgrade in November 2014, the first visit by an Albanian Prime Minister since Enver Hoxha’s in 1946, it was more or less taken for granted that Kosovo would be on the agenda. It was understandable that the significance of the visit was less the agenda to be discussed and more that it was being made at all. More than the subjects under consideration, the attention of regional and international media, and of European diplomats, was concentrated simply on the notion that a Prime Minister of Albania was visiting Serbia after many decades of hostility. The symbolism of transformation was clear: ‘The two great Balkan rivals’ were putting the past behind them and moving towards peace.

But by the same token, besides agreements-in-principle to co-operate, the frailty of the relationship between Albania and Serbia did not encourage an agenda of immediate bilateral interactions, much less top-level meetings between the two governments. Meanwhile, at least three factors suggested that Kosovo would not be on the agenda of the two Prime Ministers.

First of all, Kosovo has been an independent state since 2008, recognized by more than one hundred states including Albania. Although Serbia has yet to recognize Kosovo, the two have been in a dialogue process for the past three years and have signed a number of agreements, thanks to the mediation of a third party, the European Union. The inclusion of Kosovo on the bilateral agenda between Albania and Serbia – in practice the inclusion of a third state – would be wholly inappropriate, raising the risk of a perception or interpretation that Kosovo is an issue to be decided between those two. This had not even happened before 2008, when after the fall of Milošević Kosovo’s status had still been under discussion. From the democratic changes of that period through to Kosovo’s independence, Albania had never attached conditions to the relationship with Serbia. Throughout the period, in an effort to stimulate dialogue and co-operation with Serbia, Albania adopted the formulation of agreeing to disagree when it came to the future of Kosovo.

Secondly, although the possibility of Albania successfully influencing and encouraging states who have not recognized Kosovo to do so cannot be ruled out, this has to date never happened and there seems little chance that it will[41] – among other factors because Albania is herself a small and weak state where the international community continues to a considerable extent to intervene in domestic and foreign affairs. Much less might Albania be expected to be able to influence Serbia to recognize independence.

Thirdly, the inclusion of an issue such as the independence of Kosovo, about which Albania and Serbia have diametrically opposed views, in a meeting happening after several decades of antipathy, would not improve the meeting or the likelihood of a new spirit in relations between the two, still overshadowed by the myth of historical enmity.

A further circumstantial factor excluding Kosovo from the high-level agenda was the infamous incident in the Belgrade football stadium, when a drone was flown carrying a flag interpreted as showing a Greater Albania. Only one week before the Albanian Prime Minister’s visit to the city, the two countries nearly slipped back into a hostility redolent of the past. Within twenty-four hours the two governments had exchanged protest notes.[42] The Ambassadors of the two countries were summoned urgently to the respective diplomatic headquarters. Senior officials of the two countries became involved in declarations, polemics and even long-distance accusations.

These and other details bore a terrible resemblance to the atmosphere of the Cold War seventy years earlier, when Albania and the Yugoslavia of Tito put an end to their honeymoon (1948). The myth of historical enmity between Albanians and Serbs in the Balkans reappeared in inter-state relations between Albania and Serbia unexpectedly and in the most absurd fashion.

Nevertheless, however irrational and unnecessary it was to include Kosovo in the first meeting of the Prime Ministers of Albania and Serbia after seventy years, it was included, and public discussion of the two Prime Ministers’ differing attitudes to the Kosovo state almost eclipsed the importance and symbolism of the whole visit. The Albanian Prime Minister’s disproportionate speech in Belgrade about ‘the Kosovo issue’ was welcomed by Albanian political leaders[43], especially in Albanian patriotic circles outside Albania, and even by some political leaders in Kosovo.

In a similar fashion in Serbia too, Kosovo served as a ‘proxy war’ for nationalists, populists and even Prime Minister Vuçiç himself, who expressed his regret at what he called ‘the Albanian Prime Minister’s provocation’, while local media unanimously exalted his ‘decisiveness in confronting provocations and defending Kosovo, the independence of which will never be recognized’.[44]

On the other hand, the government and officials in Kosovo were more restrained in describing this ‘patriotic act by the Prime Minister of Albania in the middle of Belgrade’, and among almost neutral comments underlined the fact that Kosovo and Serbia were at that moment in a process of dialogue with each other. The then-Prime Minister of Kosovo, Hashim Thaçi, while ‘congratulating Rama for his resilience about the necessity of a recognition of the reality of an independent Kosovo’, emphasized the matter of the dialogue between Serbia and Kosovo.[45] Meanwhile, independent analysts in Tirana and Prishtina highlighted the efforts of Rama and Vuçiç to project an image of co-operativeness, to Brussels and other western centres of decision-making, as an important factor of the meeting.[46]

But efforts at a new rapprochement between Albania and Serbia were not well-received in Kosovo. From their initial lack of enthusiasm and neutral attitude, political leaders there became increasingly critical of what was happening between Tirana and Belgrade. They judged that the former was being rushed into deepening its relations with the latter.

Why this reserve in Prishtina about Tirana’s rapprochement with Belgrade? From the political perspective, engaged in a process of dialogue with EU mediation, Kosovo and Serbia had managed to resolve or at least to set on the path to resolution a number of practical issues between their countries, with impact on the daily lives of citizens, regardless of Serbia’s non-recognition. From the economic perspective, there was more substance in Kosovo’s relationship with Serbia than in that with Albania.

However, it seems clear that Kosovo’s irritation and opposition was related neither to the development and deepening of the economic relationship between Albania and Serbia, nor to the fostering of inter-state relations or proximity per se. The initially guarded and eventually hostile attitude of the Kosovo government is related to the fact that Albania as well as Serbia continue to hold Kosovo on their bilateral agenda, when de facto Serbia has no sovereignty in Kosovo and de jure Albania has recognized the country’s independence, as have more than one hundred other states, the majority of the UN Security Council, most of the world’s great powers and almost all democracies.

ALBANIA AS KOSOVO’S MOTHER-COUNTRY IN ALBANIA-SERBIA DIPLOMACY

When in 1913 the European powers moved towards the recognition of an Albanian state, while dividing the Albanian lands, the Albanian state that they created became the mother-country for Kosovo and other states with Albanian populations, which would come to represent distinct communities in the Kingdom – and, after the Second World War, the Federation – of Yugoslavia. For most of her first one hundred years, Albania could not play this role, who remained outside her state borders with minority status. Even after the fall of the communist regime and the end of the Cold War, a weakened and even vulnerable Albania lacked the strength for the role, relative to Kosovo and to other Albanian minorities in a Yugoslav Federation that was starting to collapse in violence.

Albania was explicitly supportive of western policy in the Balkans, and her attitude to Kosovo independence was no different to that of the USA and various European powers. Although political leaders in Albania frequently declared that they supported Kosovo independence, Tirana’s official policy could not develop a distinct, autonomous view or option regarding the future there, at least until the Kosovo War. It would seem more than merely paradoxical or ironic that, having for well-established historical reasons never played the role of mother-country for Kosovo, Albania is now trying to do so, a hundred years on and when Kosovo is an independent state. There can be no doubt that since 2008 Albania can no longer be Kosovo’s mother-country, but the possibility of playing the role for the Albanians of the Preshevo Valley – a minority within Serbia – is still open to debate. It is entirely natural that the mother-country for the Albanians of the Valley should be Kosovo and not Albania, bearing in mind that they are in an economic and cultural network linking them to the former before it links them to the latter.[47]

But if Albania cannot play the role of mother-country to Kosovo even in theory, is Albania’s insistence on including Kosovo on the agenda of talks with Serbia a proxy war? Albania has consistently aspired to be ‘rewarded’ for her moderate policy in a Balkans bedevilled by bloody conflicts, disagreements and tensions that continue to this day. The international community has often spoken of Albania’s constructive role, and Albania has expected something in return for her constructiveness, the kind of reward that in the Balkans is usually linked with western support for individuals, for leaders and not for the states they lead. Today, this role for Albania in the Balkans has come to be diminished, for at least three reasons. Firstly, the recognition of Kosovo as an independent state with her own state institutions and government has naturally reduced Tirana’s potential scope. Secondly, Albania’s efforts to influence developments in Kosovo (and also North Macedonia) are increasingly seen as a paternalistic approach, which would also explain the increasing ambivalence of the political elite in Kosovo. Thirdly, Tirana’s attempts at political influence over Kosovo have become clientelism, in favour of particular parties or, worse, individuals. Additionally, and no less important, intermittent crises in Albania almost to the point of state failure have eroded her legitimacy, reputation and capacity to play a leading role as a model for Albanians in the Balkans.[48]

Efforts to establish a new atmosphere in relations between Albania and Serbia are in fact efforts for the normalization of bilateral relations. At first glance it appears paradoxical that two states which have no fundamental issue of disagreement between them should find the normalization of relations difficult – provided that neither of them puts their attitude to Kosovo on the agenda. And the inclusion of a third state on a bilateral agenda is itself a paradox.[49]

Given that the European Union was playing the role of third-party mediator in the normalization of relations between Serbia and Kosovo, what was the point of the same role being attempted by Albania, a small and weak state, not to mention the mother-country at least in theory of Kosovo until 2008? Furthermore, Albania has no mandate to negotiate with Serbia on Kosovo’s behalf, and there is no expectation – neither in Belgrade nor in Tirana – that Albania could influence Kosovo-Serbia relations.[50] Kosovo herself is against a mediating role for Albania, and because ‘Albania is not a global player like the USA or the EU’ it is rather they, who also have instruments of influence, whose support Kosovo seeks in her engagement with Serbia.[51]

But if Albania is a small and weak state, with a high degree of international intervention in her domestic and foreign affairs, and if Kosovo herself does not want Albanian intermediation in her relations with Serbia, and if an international force of the power of the EU has taken the role, why does Tirana insist on keeping the ‘Kosovo issue’ – a term that in essence symbolizes a mythical concept for political post-communist Albania – on the bilateral agenda with Serbia?[52]

THE RISKS OF KEEPING AN ELEPHANT IN THE ROOM

For the last thirty years, right from the dissolution of Yugoslavia, there has been a proxy element to Albania’s ‘battle’ over the ‘Kosovo issue’. Before and after independence, the Kosovo issue was used by Albania’s political leaders, firstly to advance their short-term domestic political interests, and secondly and perhaps more importantly to win legitimacy in the eyes of the international community for their moderate and constructive policy in the region. On the other hand, political leaders in Kosovo have well understood the proxy element within Albania’s support and contribution – and at the same time have used their connections and influence in Albania for their own domestic political interests. There have been ample disagreements and polemics in the complex relationship between Tirana and Prishtina, but for the first time there has also been a perceptible tension between the ‘two brothers’. The ‘battle’ that Tirana is currently waging with Belgrade over Kosovo gives the impression that Kosovo, actually a third state, is merely an issue to be resolved between Albania and Serbia.[53]

Tensions between Kosovo and Albania rose more significantly after the Albania Prime Minister’s visit to Belgrade in October 2016. Initially, independent voices in Prishtina compared Albania’s attitude to Kosovo with Serbia’s to the Republika Srpska, and regarded this approach as entirely unacceptable.[54] These very critical voices towards Tirana’s approach were joined by the Kosovo Government, in the form of comments by the Minister of Foreign Affairs who warned Tirana that ‘as regards the normalization of Kosovo-Serbia relations, Kosovo herself is a political actor, and Albania should be clear about this arrangement now and in the future’.[55]

Kosovo and the issue of her relations with Serbia have increasingly featured on the agenda of bilateral relations between Albania and Serbia, something that would normally be seen as the business of the third state and within the purview of the government of that state – in this case Kosovo.[56] Albania and Serbia have produced proposals for projects in the sector of road infrastructure, but the implementation of these projects – for example the highway between Durrës and Nish – implies the involvement of the third state geographically between them: Kosovo. The signing of bilateral protocols between the two for such projects caused discontent in Prishtina, alarmed that the protocols acknowledged Serbia’s sovereignty over Kosovo.[57]

It was not only the existence of the elephant in the room, and the elephant’s escape in 2008, that made Albania’s – and Serbia’s – proxy war for Kosovo dangerous as well as unnecessary. With the new rapprochement between Albania and Serbia, the former did not hide her ambition to lead – together with the latter – reconciliation between Albanians and Serbs in the Balkans.

According to the Albanian Prime Minister, ’Serbia and Albania must look forwards, doing together for the Balkans what Germany and France did for Europe after the Second World War.’[58] But could the Franco-German model be implemented in the case of Albania and Serbia? Enmity between the Serbs and Albanians is a myth, not so similar to Franco-German rivalry and past hostilities. And above all, in the modern contest between Albanians and Serbs, the issue of Kosovo has been central. Besides a conflictual atmosphere – and forgetting the efforts of Serbia, Montenegro, Greece and the European powers to divide up the Albanian lands on the eve of the creation and recognition of independence, Albania and Serbia have never fought one other as two independent states, as Germany and France did until the end of the Second World War. War, genocide, mass killings and wholesale evictions have occurred in Kosovo, not in Albania. In these circumstances, is it possible for Albania to lead efforts at reconciliation between Albanians and Serbs in the Balkans?[59] Kosovo President Hashim Thaçi has a clear and unequivocal answer to the question: ‘Full normalization of Albanian-Serb relations doesn’t pass from Belgrade through Tirana, but from Prishtina.’[60]

It is now becoming ever more clear that relations between Albania and Kosovo are not without tensions and clashes, sometimes accompanied by harsh rhetoric. At the same time, the sources of these tensions and disagreements are various. The first is economic, and related chiefly to trade exchanges. The border between Albania and Kosovo, in fact a border dividing one people, intermittently flares up in a minuscule war over honey, potatoes or milk. Behind the facade of excellent relations, it appears that the two countries are reluctant to step back from the factors obstructing an easing of trade, let alone to implement new more favourable arrangements.[61] In any case, tensions arising from economic issues are lower profile, and rarely attract the attention and engagement of Kosovo’s government or political institutions.

Rising tensions and serious disagreements between Albania and Kosovo are in fact political in character, and related to Albania’s relations with Serbia, which reflect Albania’s consistently and increasingly paternalistic attitude to Kosovo.

After the political tensions that accompanied Albania’s 2016 initiative with Serbia to lead reconciliation between Albanians and Serbs in the region, tensions and disagreements recurred during 2018 and then particularly in the second half of 2019. In both periods, the root of the trouble was once again the ‘strategic agenda’ in relations, in which Kosovo was once again included. In 2018 it appeared that the Albanian Prime Minister was actively supporting the achievement of an agreement between Serbia and Kosovo[62], an agreement that – as presented by Aleksandar Vuçiç and Hashim Thaçi – foresaw a territorial exchange or ‘correction of borders’. Such an agreement, the terms of which have never been made public, was not supported by other political leaders in Kosovo, fostering disagreement between them and the President and reviving tension with Tirana. It appeared that Prishtina was not willing to accept the Albanian Prime Minister’s political lead in an issue belonging exclusively to Kosovo and her institutions, especially bearing in mind the fact that the Kosovo President had not shared and was not ready to share with Kosovo’s parliament or government the concept or core of an agreement that the Albanian Prime Minister was aware of.[63]

With the other European powers taking different positions, Germany did not support a Serbia-Kosovo agreement based on land-swap/border correction in the Balkans[64], while it appeared that Washington was ready to back the resolution of the frozen conflict between Serbia and Kosovo even if it involved an agreement based on a correction of borders[65], provided that it was accepted by both states.[66] The western supporters – the USA but also others – of a reconciliation agreement between Serbia and Kosovo even involving change of borders[67] seemed to over-estimate the role that Albania and especially her Prime Minister could play in convincing Kosovo to accept the agreement. At the same time, although Prishtina had consistently refused to accept Tirana’s paternalism and activism in fundamental issues for Kosovo, especially in relations with Serbia and similar issues, the Albanian Prime Minister involved himself as a supporter of the Serbia-Kosovo agreement, almost to the extent of becoming an active player in the process, striving persistently to appear as a leader with influence among all of the region’s Albanians. Two proposals from the Prime Minister seemed to serve to reinforce his claim to leadership in the Albanian lands regardless of the fact that those lands are now divided into independent states: the first in 2018, when he suggested to the Kosovo Parliament that Albania and Kosovo should have a joint President, as a symbol of national unity[68], and second when he named as Foreign Minister of Albania[69] a young man from Kosovo[70].

Political tensions rose again in the second half of 2019, because of the joint initiative of Belgrade and Tirana for a Balkan Schengen[71], Kosovo having refused participation categorically and with full consensus among government, President and all political parties, including the Vetëvendosja Movement which would go on to lead the government after the parliamentary elections of 6 October 2019.

CONCLUSIONS

Albania and Serbia are essential for Balkan security, stability and development. These relationships are strategic and as such they demand, above all, ownership and support on the ground rather than just from European diplomacy. The new rapprochement between Albania and Serbia seems to have support and expectations from the European powers. EU and in particular German backing for a new era in inter-state relations between them is linked to the idea of a wider reconciliation between Albanians and Serbs as ‘the great rival peoples’ of the Balkans. The deepening and broadening of their relationship could also assist the establishment of a new spirit between the peoples, but reconciliation between Albanians and Serbs should happen between Serbia and Kosovo.

For established historical reasons, Albania cannot play the role of mother-country for Kosovo or for Albanian minorities elsewhere in the Balkans, and of course any attempt to do so in the post-independence context would be absurd and damaging. Instead of clashing, Kosovo and Albania must as two distinct independent states reach harmony in their regional policies, especially as regards Albanian minorities in neighbouring states.

In the relationship between Albania and Serbia since 2008, Kosovo has not been and cannot be the elephant in the room any more. The failure to move on from this approach ignores the fact that Kosovo is an independent state, and that could have serious implications for her relations with Serbia. On the other hand, if Albania manages not to undermine Kosovo she could adapt her role to that of international player, a third party between Serbia and Kosovo, as is the European Union. Lastly, but not less important, Tirana’s proxy war has heralded tension and clashes between Albania and Kosovo. In the best case, populist tendencies in Belgrade and Tirana might maintain the status quo in their inter-state relations without allowing fundamental progress, whereas they could damage inter-state relations between Albania and Kosovo.

[1] See Serbia Vows to Adopt New NATO Plan Soon, Maja Zivanovic, BIRN, October 30, 2019 at https://balkaninsight.com/2019/10/30/serbia-voës-to-adopt-neë-nato-plan-soon/

[2] See Elez Biberaj, Shqipëria në marrëdhëniet ndërkombëtare, ed. Albert Rakipi, (AIIS, Tiranë, 2013)

[3] For the best account of Albanian Foreign Policy during the Zog era see Bernd Fischer ‘King Zog and the struggle for stability’ ,AIIS 2012.

[4] For a full summary of Albania’s relations with the Yugoslav Federation, see Elez Biberaj, “Shqipëria: një fuqi e vogël në kërkim të sigurisë” në ‘Shqipëria dhe Kina – një aleancë e pabarabartë’ (AIIS, Tiranë 2011).

[6] See: ‘Albania, Serbia take further steps to normalize relations’, in Tirana Times, May 2014 at http://ëëë.tiranatimes.com/?s=Albanian+Serbia+Relations&paged=2.

[7] Privredna Komore Srbije, Sproljnotrgovinska razmena Republike Srbije i Republike Albanije, Beograd, February 2019

[8] According to BIRN data, 3-5,000 Serbian tourists visit Albania every year, while the number of tourists from Albania visiting Serbia is too small to register. According to data from Serbia’s Ministry of Tourism, Albania is not one of the 40 countries of origin with the highest number of visitors to Serbia.

[9] According to the most recent study in September 2019 by the Institute for International Studies and the Hans Seidel Foundation, the majority of Albanians (80 percent) declare that Serbian citizens are welcome as tourists in Albania, whereas only 10 percent think the opposite.

[10] See ‘Albanian Serbian Relations in the eyes of the Albanian public opinion’, 2015, Alba Cela, Albanian Institute for International Studies, Tirana, 2015, p. 22.

[11] The majority of Albanian citizens, 69 percent, consider relations with Serbia important or very important. See the survey by AIIS and HSS, Tirana Times, December 20, 2019 at www.tiranatimes.com/.

[12] Rama to Belgrade with Air Serbia – see http://illyriapress.com/rama-ne-beograd-air-serbia-perurohet-linja-e-re-e-fluturimit/.

[13] In the event, the Albanian Prime Ministerial visit to Belgrade planned for October was delayed to November because of developments surrounding the flight by a flag-carrying drone in Belgrade’s stadium. See https://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/21/world/europe/albania-edi-rama-belgrade-trip-soccer-match-drone.html

[14] See ‘Albania PM Makes Historic Visit to Serbia’ at https://balkaninsight.com/2014/11/07/albania-pm-to-hold-historic-visit-to-serbia/, ‘Serbia-Albania row over Kosovo mars historic Rama visit’ https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-29985048 ‘Albania’s premier makes historic visit to Belgrade’.

[15] Italian Foreign Minister and incoming EU High Representation for Foreign Affairs Federica Mogherini again arranged a series of joint Tirana-Belgrade meetings under Rome’s patronage. See Albert Rakipi, ‘Albania-Serbia – What is Italy mediating?: a strategic idea that should supported; does Italy have a concrete plan?’ Europa journal Nr. 2014 at http://europa.com.al/index.php/2015/02/05/shqiperi-serbi-cfare-ndermjeteson-italia/

[16] According to a survey by AIIS and the Hans Seidel Foundation only a minority of around 20% of Albanians think that relations are bad or very bad.

[17] Survey by AIIS and the Hans Seidel Foundation

[18] Meaning the perceptions of Albanian citizens

[19] Survey by AIIS and the Hans Seidel Foundation

[20] On May 8th 2019 Serbian President Vuçiç visited Tirana in the context of the Brdo-Brijuni Summit.

[21] In the framework of the Balkan Mini-Schengen initiative, Albanian Prime Minister Rama and Serbian President Vuçiç have met three times: first in Novi Sad, in November 2019 in Ohrid and then on 21st December in Tirana.

[22] Privredna Komore Srbije, Sproljnotrgovinska razmena Republike Srbije i Republike Albanije, Belgrade, February 2019.

[23] Privredna Komore Srbije, Sproljnotrgovinska razmena Republike Srbije i Republike Albanije, Belgrade, February 2019.

[24] Meaning economic relations and trade exchange Serbia-Kosovo before the imposition of 100% duty by the Haradinaj Government.

[25] Stevan Rapaić, Ekonomski aspekti srpsko-kosovskog pitanja, p. 5.

[26] The core of this agreement is that citizens can travel using their identity cards.

[27] According to the goals of this agreement, the contracting parties, represented by their customs authorities and consistent with the provisions specified in the Agreement, will offer one another mutual assistance with the aim of ensuring that customs legislation is implemented in the correct manner, and that breaches of customs legislation are prevented, investigated and/or combatted. All assistance in the context of the Agreement in question will be given by each Contracting Party in conformity with national legislation and within the competences and capabilities of the respective Customs Authority. This Agreement refers only to mutual administrative assistance by the Contracting Parties.

[28] For a fuller analysis of the Mini-Schengen see Agon Deahaja, Tirana Observatory, vol. I, nr. 2 or at www.tiranaobservatory.com.

[29] For a clear representation of the Balkan Schengen, see: Frans Lothar Altman, Tirana Observatory, Tirana Times, Veton Surroi in Tirana Times, January 7, 2020.

[30] ‘Shengeni i vogël, Rama: Kemi vullnet për ta bërë, është kapërcim historik’, dosja.al 10 October 2019 https://dosja.al/shengeni-i-vogel-rama-kemi-vullnet-per-ta-bere-eshte-kapercim-historik/

[31] ‘The Balkans are a chessboard of Great Powers’ Vuçiç declared in the Belgrade Security Forum in October 2018, referring to the lack of German support for an agreement between Serbia and Kosovo involving border correction. See Vessela Tcherneva, ‘The Price of normalisation: Serbia Kosovo and a risky border deal’ ECFR. Eu 13 November 2018, në https://www.ecfr.eu/article/commentary_the_price_of_normalisation_serbia_kosovo_and_a_risky_border_deal

[32] The well-known fairytale of ‘the Balkans for the people of the Balkans’.

[33] ‘Shengeni i vogël, Rama: Kemi vullnet për ta bërë, është kapërcim historik’, dosja.al 10 October 2019 https://dosja.al/shengeni-i-vogel-rama-kemi-vullnet-per-ta-bere-eshte-kapercim-historik/.

[34] Kosovo has featured in meetings and debates, especially those in public regarding generally technical issues (discussions about the Trepça mines, movement of vehicles in the north of Kosovo with number plates from Serbia or Kosovo, Serbian release of the Mitrovica Director of Police, and similar matters) which ought to be addressed by Serbia and Kosovo, but not by Serbia and Albania.

[35] According to the survey by AIIS and HSS, only 10 per cent think that reconciliation between the peoples depends on relations between Albania and Serbia. See Tirana Times.

[36] Indeed, by a substantial majority – 77 per cent – Albania’s citizens judge that it depends on reconciliation between Kosovo and Serbia.

[37] ‘Shengeni Ballkanik/ Kurti: Rruga nga Beogradi për në Tiranë kalon nga Prishtina! Bashkëpunim jo konfrontim’, Shqiptarja.com 23 December 2019, https://shqiptarja.com/lajm/rruga-nga-beogradi-per-ne-tirane-kalon-nga-prishtina-albin-kurti-reagon-per-shengenin-ballkanik-kemi-nevoje-per-bashkepunim-jo-konfrontim.

[38] Survey by AIIS and Hans Seidel Foundation, September 2019.

[39] Survey by AIIS and Hans Seidel Foundation, September 2019.

[40] ‘15 countries, and counting, revoke recognition of Kosovo, Serbia says’ Euractiv https://www.euractiv.com/section/enlargement/news/15-countries-and-counting-revoke-recognition-of-kosovo-serbia-says/

[41] In 2015 Albania played a leading role in Kosovo’s efforts to join UNESCO, but the efforts thanks to the abstentions of several states that had already recognized independence.

[42] The Albanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs presented a protest note to Serbian Government on 16th October 2014, in which it emphasized that the Albanian Government ‘decisively rejected the political mud-slinging by the leaders of Serbia against the Albanian people and state’. See Voice of America, http://www.zeriamerikes.com/a/deklarat-e-ditmir-bushatit/2486075.html. The Albanian Government’s protest note was in fact a reply to the protest note from the Serbian Government.

[43] http://infoalbania.al/adem-demaci-dhe-menduh-thaci-vleresojne-deklaratat-e-rames-ne-beograd/. The According to the activist Adem Demaçi, the Albanian Prime Minister’s speech in Belgrade was a courageous act. For him, Rama had shown the world that the Serbs continued to play a hypocritical role. ‘By his visit to Belgrade, Rama put an end to the centuries-old illusion of Serb politics that Albania should not speak for Kosovo. Albania showed Serbia that she is independent of Europe and Edi Rama showed them how they should act. He showed them that Serbs should be seen from Europe and that when it comes to Kosovo they should not dream with their eyes open.’ Demaçi declared.

[44] ‘Serbia-Albania row over Kosovo mars historic Rama visit’, BBC NEWS 10 November 2014, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-29985048

[45] See Maja Ponatov ‘“Historic” Albanian visit to Serbia leaves bitter aftertaste’ at https://www.euractiv.com/section/enlargement/neës/historic-albanian-visit-to-serbia-leaves-bitter-aftertaste/ November 13, 2014.

[46] See Enver Robelli ‘Vizita e Edi Ramës në Beograd dhe Selamet e panevojshme nga Kosova.’ Koha, net 12 October 2014

[47] ‘Rama Takohet me Vuçiç, Të bëjmë atë që Franca dhe Gjermania bënë pas Luftës së Dytë Botërore’; see Gazeta Dita, 21 April 2015.

[48] See ‘Talking Albanian Foreign Policy’, Tirana Times, May 27, 2016 http://www.tiranatimes.com/?p=127767.

[49] Almost as paradoxical was the Italian offer in summer 2014 to serve as an intermediary between Albania and Serbia, when there was no disagreement between them that needed intermediation by a third party, especially if a third state – Kosovo – was not brought into the matter of their relationship.

[50] See: ‘Serbia-Albania Relations: A Fragile Work in Progress As Albania’s PM visits Serbia, experts argue that improving Belgrade-Tirana relations are a result of their leaders’ hope of pleasing the EU rather than a real breakthrough between the two countries’, Natalia Zaba. See also at: http://www.balkaninsight.com/en/article/serbia-albania-relations-a-fragile-work-in-progress-10-13-2016#sthash.cTXRwJYa.dpuf.

[51] Comment by Foreign Minister Hoxhaj; see http://www.gazetadita.al/hoxhaj-nuk-na-duhet-ndihma-e-shqiperise-per-dialogun-me-serbine/.

[52] Ever since the break-up of Yugoslavia and throughout the past 25 years, it has been on the agenda for any meeting with a third-party by the President, the Prime Minister, the Foreign Minister and even local Mayors.

[53] During the most recent meeting in Belgrade between the Prime Ministers of Albania and Serbia, in October 2016, Kosovo was the issue that dominated a public debate between the two in front of an audience of students and journalists. For more, see Belgrade Security Forum, October 2016.

[54] See Dastid Pallaska ‘Pallaska: Shqipëria nuk mund të sillet me Kosovën si Serbia me Republikën Srpska. Sipas analistit dhe Juristit Pallaska “Republikën Srpska e ka krijuar Serbia, ndërsa Kosovën e kanë krijuar njerëzit e saj me luftë dhe me ndihmën e bashkësisë ndërkombëtare.”’ http://telegrafi.com/pallaska-shqiperia-nuk-mund-te-sillet-kosoven-si-serbia-republiken-srpska-video/.

[55] http://www.gazetadita.al/hoxhaj-nuk-na-duhet-ndihma-e-shqiperise-per-dialogun-me-serbine/.

[56] In an informal yet public meeting of the Albanian and Serbian Prime Ministers in Belgrade, on 12th October 2016, the issues dominating the discussion were the Kosovo government’s decision to nationalize Trepça, the arrest of the Director of Police of Mitrovica, and the like.

[57] For the signing of a co-operation protocol between Serbia and Albania see regarding infrastructure projects see Laura Hasani, ‘Shqipëria dhe Serbia ‘zhbëjnë’ Kosovën’.

[58] Ibid.

[59] ‘Pajtimi shqiptaro-serb: Këpucët e mëdha për Ramën dhe Vuçiçin’, Enver Robelli, Koha Jonë, 24.10. 2016

[60] Remarks by Kosovo President Hashim Thaçi on Klan Kosova TV.

[61] ‘Pas Serbisë, Kosova kërcënon edhe Shqipërinë me taksë 100%’, Gazeta Express 22 May 2019 https://www.gazetaexpress.com/pas-serbise-kosova-kercenon-edhe-shqiperine-me-takse-100/.

[62] See Marcus Tanner, ‘Correcting Kosovo’s Border Would Shake Postwar Europe’s Foundations’ at https://balkaninsight.com/2018/08/24/correcting-kosovo-s-border-would-shake-postwar-europe-s-foundations-08-24-2018/.

[63] Interview with a senior official in the Foreign Ministry of the Republic of Kosovo.

[64] Nenad Kreizer, Darko Janjevic, A Cold War solution for Serbia and Kosovo?, DW 29.04.2019 https://www.dw.com/en/a-cold-war-solution-for-serbia-and-kosovo/a-48527182.

[65] ‘Bolton Says U.S. Won’t Oppose Kosovo-Serbia Land Swap Deal’, Radio Free Europe August 24, 2018 https://www.rferl.org/a/bolton-says-u-s-won-t-oppose-kosovo-serbia-land-swap-deal/29451395.html

[66] Special Representative for the Western Balkans Matthew Palmer – Speech in Pristina, November 1, 2019. U.S Embassy in Kosovo, https://xk.usembassy.gov/special-representative-for-the-western-balkans-matthew-palmer/.

[67] It was never made clear how the border could be changed without priori recognition by both states of the existing border.

[68] ‘Edi Rama: Kosova dhe Shqipëria do ta kenë një president të përbashkët, të unitetit kombëtar!’, Bota Sot, 18 February 2018 https://www.botasot.info/lajme/837341/edi-rama-kosova-dhe-shqiperia-do-ta-kene-nje-president-te-perbashket-te-unitetit-kombetar/.

[69] A young woman from Kosovo was likewise appointed as Minister of Education

[70] The two gestures were greeted with surprise, and though there was no public statement, Prishtina let it be known that it did not agree with the idea of a common President. When the President of Albania refused to approve by decree the nominee for Foreign Minister, the Prime Minister reacted by publicly apologizing to Kosovo, reinforcing the impression that the Kosovan nominee as Minister would represent Kosovo in the Albanian government. Meanwhile, Kosovo Prime Minister Haradinaj fought fire with fire by emphasizing that nominations to the government of Albania were a matter for Albania and the Albanian Prime Minister, and not for the Republic of Kosovo – http://rtv21.tv/haradinaj-nuk-komentoi-mosdekretimin-e-gent-cakajt/.

[71] For a fuller analysis of this theme, see Agon Demjaha ‘Balkan Mini-Schengen: A Well Thought Regional Initiative or a Political Stunt?’ Tirana Observatory, Winter 2019, Vol 2.