LULZIM PECI

ABSTRACT

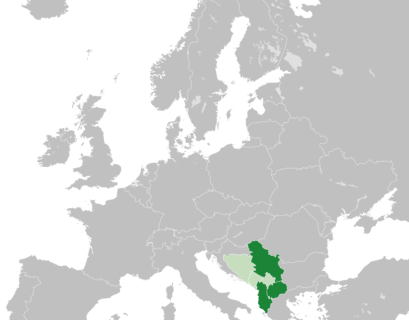

After the liberation of Kosovo in 1999 and its declaration of independence in 2008, opportunities emerged for more intensive bilateral relations between Kosovo and Albania. However, in despite of this newfound momentum for increased cooperation, the opinion prevails that bilateral cooperation in general is formal and emotional, rather than substantial and in the interest of citizens. Recently, the stumble and delay of the process of integration of Albania and Kosovo in the European Union has increased the nationalist tendencies in both countries, and has vocalized the issue of unification of the two states. Furthermore, dissatisfaction toward the European Union regarding its noncomittal stance on enlargement has sparked renewed interest in unification among well-connected politicos in both Tirana and Prishtina, though for popullist purposes.

During the last two years, the idea of the unification of Kosovo and Albania was among the most prominent issues in the public discourses of both countries. This idea, as well as its implications for both countries, were not elaborated profoundly, and particularly regarding their implications in relation to the International Law and the key international institutions, namely, the United Nations, NATO, and the European Union.

The goal of the following paper is to deconstruct the idea of potential unification of Albania and Kosovo by analyzing possible implications of different modalities of this issue. Particularly the international considerations will be analysed as they have a direct impact on the feasibility and sustainability of the idea of unification of the two countries. The external considerations are acknowledged in unification proposals, drawing on the international law literature. The paper also sheds light on how international bodies, such as the United Nations (UN), the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), and the European Union (EU), would respond to an proposed unification plan.

The Modalities of the Unification and Association of Independent and Sovereign States

The conscience of “peoples“ or “nations“ for (re-)constituting particular political-legal entitites has always been an essential factor in international relations. The importance of this geopolitical parameter has increased significantly from the 19th century, and in the first part of the 20th,[2] and has continued to unfold up to the recent days. However, the transformation of ethnic and cultural affinities in a single territorial organization is, neither easy, nor simple, as was shown in the cases of the creation and dissolution of the states in the Balkans during the last two centuries. The Albanian people, when compared with other peoples in the Balkans, are not an exception from this phenomenon. Their independence struggle began with the movement for the creation of an independent Albania (1908–12), and reached its apex with the declaration of independence of Kosovo (2008).

From this point of view, International Law does not recognize “divided peoples“ as a particular legal category, whereas the very concept of “divided states“ is seen as useless in the legal aspect, in despite of the fact that sometimes they can be treated as a single state divided in different entities. However, in respect to International Law, such cases are refered to general principles of statehood and succession, rather than to any particular legal category.[3] Consequently, in the domain of international law, Kosovo and Albania, given that they were never a single state, cannot be treated with the narrative of the divided states, as was the case of the two Germanies, or that of China, Vietnam, and the two Koreas, after the Second World War.

For this reason, the deconstruction of the idea of unification of Kosovo and Albania must be viewed through the prism of unification between two sovereign states. Moreover, in this particular case, Albania enjoys the full international legitimacy, while Kosovo is confronted with the challenge of truncated legitimacy and partial integration in international organizations, which makes the discussion of this deconstruction even more difficult.

In analogy with the process of the creation of new states, International Law, in general, remains silent regarding the unification of two independent states as well – except for the cases when this touches upon the jus cogens [compelling law] norms, or any particular international obligation (for instance, when there is any particular agreement/treaty which refers to some particular situation). In most of the cases, however, the unification of independent and sovereign states is treated through succession of states. This implies the replacement of one state with another one, regarding the responsibility in international relations for the territory in question.

However, the issue of succession in International Law is not fully regulated. In this respect, many practices of succession were developed as a consequence of particular political changes, which, on the other hand, were not treated in a consistent manner by the international community.[4] In a large measure, the international aspects of succession are recently regulated by the Vienna Convention on Succession of States in Respect of Treaties (1978),[5] and the Vienna Convention on Succession of States in Respect of State Property, Archives and Debts (which has not entered yet into force),[6] and this reflects the state of contemporary International Law.[7]

On the other hand, under international law, there are two methods of unification of two independent and sovereign states. One is mergering two entities into a completely new state, a situation that unfolded when the Arab Republic of Yemen joined with the Democratic Republic of Yemen in 1990. The second is the voluntary absorbtion of one state by the other, in which case the absorbed state ceases to exist, while the absorbing one preserves its state continuity with an increased territory and population (such as the case of two Germanies).[8]

Other forms of integration of states, but not of their political unification, is the one of associated states. These refer to states which have the international subjectivity of their own as independent states, but due to their smallness and limited human resources, have forged particular relations with some bigger states that usually take the role of their protectors. Examples include the associations betwen Lichtenstein and Switzerland, Monaco and France, and San Marino with Italy. Another type of arrangement can be seen in Commonwealth, which is another form of association of independent states that gathers sovereign countries based on common interests and their historic ties. Meanwhile, the most advanced form of the associated states is the European Union, a regional organization that imposes its laws to its member countries, negotiates agreements with third parties, and represents itself in international organizations.[9]

However, as far as succession of states that are united is concerned (the states that were merged, or enlarged through the absorption of one state by another), their membership and contractual relations in international organizations depend on the norms and legal regulations of the respective organizations. Meanwhile, given that member countries of association of states have distinct international legal personality and enjoy distinct membership in international organizations, legal provisions of the succession in cases of their association with one-another are consequently inapplicable.

With this in mind, the deconstruction of the idea of unification of Kosovo and Albania will be discussed through the options of absorption of Kosovo by Albania, of the merger of Kosovo and Albania into a new state, and of their association with one another as independent states. This will be done from the point of view of the options of unification in relation with considerations and implications of the (non)-membership in the United Nations, NATO, and the integration process and membership of the two countries in the European Union.

The Options of Unification and of Association in Relation to the United Nations

Regarding the succession of membership in a case of creation of a new state through merger of two member states, the legal framework of the United Nations provides the replacement of the membership of predecessor states in this organization with the membership of the new state, and in the case of a voluntary absorption of one state by another, the membership of the absorbed state in this organization ceases to exist.[10]

When thinking of Kosovo’s absorption into Albania, the membership of Albania in the United Nations will continue. However, the legality of the absorption of Kosovo could be challenged by a number of the UN member countries given the country’s disputed international status.

Moreover, if Prishtina and Tirana undertake such a step without prior support of the Western countries who are permanent members of the Security Council of the United Nations, it is likely that severe measures might be taken against both, Albania, and Kosovo, including here the re-enactment of the provisions of the Resolution 1244 (1999), as well as the imposition of sanctions against Albania. Furthermore, even if measures against such an act are blocked by any from the permanent members of the Security Council, they can be proceeded by the General Assembly of the United Nations to the International Court of Justice, and this can bring unanticipated consequences for both countries, notwithstanding the fact that this court can provide only advisory opinions.

Undertaking of this step will give an irreparable blow to the statehood of Kosovo, rendering its sovereignty into a bargaining issue between Tirana and Belgrade. In this situation, Serbia and its allies could challenge the absorption deal by arguing that the Resolution 1244 (1999) considers Kosovo as part of Serbia. Furthermore, in accordance with the Articles 25 and 103 of the Charter of the United Nations,[11] Albania should give priority to the Resolution 1244. On the other hand, Albania can use as an argument the Advisory Opinion of the International Court of Justice, and the point 113, based on which the political solution of the status of Kosovo is outside of the scope of the Resolution 1244 (1999). Having in mind the actual international constellation regarding the independence of Kosovo, such a scenario would be ideal for satisfying the territorial apetites of Serbia towards Kosovo, which in such a situation would not end only on the North of the country, but would extend into other parts of Kosovo inhabited by the Serbian community as well.

On the other hand, in the case of membership of Kosovo in the United Nations, the realization of any option of unification between Prishtina and Tirana should not have any consequences by this organization, except for the case of substitution of the Resolution 1244 (1999) with some other resolution of the Security Council, which would explicitly prohibit Kosovo from unification with other countries or with parts of their territories. In the last scenario, the unification of Kosovo with Albania, either through merger, or through absorption, would present clear violation of the International Law, in which case both countries could be sanctioned for undertaking such an action, and eventually they would be constrained to undo their unification.

Meanwhile, the option of association of Kosovo with Albania, which would involve the modalities of cooperation and integration between the two countries up to the level of creation of a new legal international personality, cannot be expected to cause reaction by the Security Council and the Assembly of the United Nations, given that this option would not imply in any form the delegation of any part of the sovereignty of Prishtina to Tirana, or the common sovereignty of two countries over the territory of one another.

However, if the association between Prishtina and Tirana reaches the level of the creation of a new international legal personality, at the time when Kosovo does not enjoy the status of the United Nations member, this can cause reaction by certain countries of the Security Council, as well as among those in the General Assembly, which can challenge the legality of this association, in the most extreme case by proceeding it to the International Court of Justice, for interpretation of the “treaty of association“ in relation to eventual violation of the International Law.[12]

The Options of Unification and Association in Relation to NATO

In contrast to United Nations, which have regulated the succession of member states in the event of unification, the North-Atlantic Treaty does not regulate this issue explicitly.[13] Moreover, membership in NATO is not limited to countries that are members of the United Nations.[14] On the other hand, the first and the only case up to now of a unification of a NATO country with a non-member was the one of the absorption of the Democratic Republic of Germany by the Federal Republic of Germany, in fall 1990, which was treated widely in the academic literature.[15]

German unification, which was achieved through the implementation of the Treaty on Unification between the Federal Republic of Germany and the Democratic Republic of Germany of August 31st, 1990,[16] was a result of extraordinary circumstances that emerged in Europe with the end of the Cold War. Specifically, the Four Power Authorities (Soviet Union, Great Britain, France, and the United States of America) agreed to support the absorption of the Democratic Republic of Germany by the Federal Republic of Germany, including the membership of this enlarged state in NATO.[17]

This case created an important precedent, the one of the unification of a NATO member country with another country that is not a member of the alliance. From the legal point of view, the NATO member countries previously provided support to the unification of two Germanys, at the meeting of the North-Atlantic Council at the ministerial level of June 7–8, 1990, in which they took the decision to extend the security guarantees specified in the Articles 5 and 6 of the North-Atlantic Treaty to the entire territory of the united Germany.[18]

In principle, Albania as a member of NATO, and Kosovo which is not its member, based on the precedent of the German unification, theoretically can unite through the absorption of Kosovo by Albania, if such an option would obtain the prior support of all the countries that are members of NATO, for extending the guarantees of the Articles 5 and 6 of the North-Atlantic Treaty in the entire territory of this enlarged state. Moreover, the fact that Kosovo is not a member of the United Nations would not cause a problem for NATO regarding the extension of its security guarantees to the territory of Kosovo.

Nevertheless, the implementation of this scenario in the current situation is almost impossible, given the non-recognition and contestation of the independence of Kosovo by four members of NATO (Greece, Romania, Slovakia, and Spain), as well as by Serbia which continues to consider it as a part of its territory. However, even if these issues would be solved in some future, it is difficult to imagine that the key members of NATO, but also the other countries in the region, would agree with the unification of Kosovo and Albania, not only because of the balances in the region, but also because of the possibility of emergence of new cases of similar nature, such as, for instance, the case of unification of Moldova with Romania.[19]

Another issue that is to be raised here is the one of the consequences of undertaking of some unilateral act of unification of Kosovo with Albania, either through absorption, or through merger, in the current situation in which the statehood of Kosovo is contested by four NATO members. If Kosovo would be absorbed by Albania through such an act, it will loose its statehood, and, at the same time, its territory would not be covered by the security guarantees of NATO that are provided to its member countries. Moreover, if such an act will be taken in opposition to the USA, France, and Great Britain, one from the possible consequences would be the re-enactment of the Resolution 1244 (1999) of the Security Council of the UN, implying the possible return of the full authority of UNMIK (the Mission of the United Nations in Kosovo), the suspension of national authorities and the enactment of the component of peace implementation by KFOR, which, in practical terms, would return Kosovo’s statehood to point zero, that is, in June 1999.

On the other hand, despite of the fact that NATO does not have legal provisions for the suspension of its members,[20] in such a case, based on the Article 60 of the Vienna Convetion of the Law on Treaties (1960),[21] the member countries could claim that Albania has conducted “material violation” of the North-Atlantic Treaty, and would suspend and discontinue its membership in the North-Atlantic Treaty.[22] Such a scenario would be fatal to Albania (as well as to all the Albanians in the region), given that it will loose its membership in NATO, and will be considered by the Western world as a “rogue state,” that is, a country that endangers the international order and security.

In current circumstances, if Kosovo and Albania decide to merge through an unilateral act, the consequences would be approximately the same as those in the case of the absorption of Kosovo by Albania. A minor difference would be that Albania’s membership in NATO would be thrown into jeopardy. Opponents could charge that since Albania has ceased to exist as a state, its membership in NATO should also be voided.

In a case when Kosovo is recognized by all NATO members, which might be expected to happen after its recognition by Serbia, in a situation when Albania is member of NATO and Kosovo does not enjoy this status, the undertaking of any unilateral steps towards unification of both forms would have similar implications with the above scenarios, with the difference that Kosovo would voluntarily loose its statehood, including here its possible membership in the United Nations, while Albania would endanger its suspension and discontinuation of its membership in NATO. This could have unpredictable consequences for both countries, which would hardly be repairable for a very long time.

An interesting scenario to be discussed is the option of unification of Kosovo and Albania in a situation in which both countries would be members of NATO, without prior approval by all the other member countries of the North-Atlantic Alliance. In the case of absorption, in despite of the fact that the territory of Kosovo would enjoy up to then the security guarantees of NATO, those guarantees can be lost, given that with this act, with the cessation of its existence as a state, Kosovo will, both, de facto and de iure, exclude itself from the North-Atlantic Alliance. Except for the undoing of Kosovo statehood, such an option could lead to the suspension or discontinuation of the membership of Albania in NATO, and these would have unpredictable consequences for both countries.

In a case of unilateral unification of Kosovo and Albania into a single state through merger, depending on the political interpretation of other NATO members, both countries could confront their own self-dismissal from the Alliance, since very easily an interpretation that both countries have ceased to exist might prevail, and that if the new state wants to become a member of NATO, it should re-apply for membership in this organization.

Regarding the option of soft association between Kosovo and Albania, for as long as it doesn’t create e new international legal person, and for as long as it doesn’t violate NATO’s defence and security policies, it cannot be expected that this option will cause any problem with NATO member countries. However, if this association is carried out unilaterally and includes a component of bilateral self-defence, this can cause problems with the countries of NATO, and particularly in a situation in which Kosovo would not be a member of the North-Atlantic Alliance. This, on the one hand, could be interpreted as misuse of the security guarantees of NATO by Albania, and, on the other, such an act could lead to suspension or even cessation of the process of integration of Kosovo in NATO.

In the case of Kosovo’s membership in NATO, the association of the two countries which would include the defence component would be completely unnecessary, given that both countries would formally be allies, and, on the other hand, the Article 3 of the North-Atlantic Treaty encourages the cooperation between its members in the development of their capacities for individual and collective defence for resisting armed attacks.[23]

The Options of Unification and Association in Relation to the European Union

While the German unification was the referent case used in the above analysis, in relation to the European Union it cannot be taken as a reference for the unification or association of Kosovo and Albania, since the unification of two Germanys (1990) was achieved before the establishment of the European Union with the Treaty of Maastricht (February 1992) and the agreement on the Copenhagen Criteria (June 1993) for candidate countries for membership in the EU, as well as prior to its further evolution through the Treaties of Amsterdam (1997), Nice (2001) and Lisbon (2007).

Thus, the following analysis of the options for the unification of Kosovo with Albania, through undertaking of unilateral steps and without prior approval of all the countries of the European Union, will be discussed through the legal lenses of the Lisbon Treaty.[24]

Albania has signed the Association-Stabilization Agreement with the European Union, in June 2006, while the candidate status for membership was given to it in June 2014. In May 2019, the European Commission recommended the opening of membership negotiations.[25] However, the green light for this was not given by the European Council on October 18,th 2019.[26] As for Kosovo, the country has only signed the Stabilization and Association Agreement with the EU[27] and it is not recognized by five EU members (Greece, Cyprus, Romania, Slovakia, and Spain).

Even if the EU opens talks on Albania’s succession in the near future, undertaking any unilateral steps towards unification of Kosovo with Albania could cause grave consequences for the European future of both countries. With the option of unification through absorption of Kosovo by Albania, the Stabilization and Association Agreement between the EU and Kosovo would be automatically undone given that Kosovo would cease its existence as a state. On the other hand, the EU might terminate or block the process of negotiations for the membership of Albania, including also the suspension of the Association and Stabilization Agreement between the EU and Albania. In the case of the option of unification through merger of Kosovo and Albania into a new state, in the EU could prevail the interpretation that this new state cannot inherit the previous contractual and integration statuses with the EU, which would effectively return the situation in relation to EU in both countries into the year 1999, but with the difference that, from the ally countries of the West, they would both become rogue states isolated from the democratic world.

In an assumed situation in which both countries would be members of the EU, and if they would unilaterally pursue unification through absorption of Kosovo by Albania, Kosovo will automatically loose its statehood and the “European regime” in its territory, including the European citizenship of its citizens. On the other hand, the membership of Albania in the EU, in the best case scenario, might be suspended with a decision by the qualified majority of the member states,[28] and in the most extreme case, it might be expelled from the EU, if this case would be interpreted based on the Article 60 of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (1960),[29] by considering that Albania has committed “material breach” of the Treaty of the European Union. In the case of unilateral unification through merger of the two states into a single one, the other member states might consider that the memberships of Kosovo and Albania in the EU have ceased to exist, and that the new state should start the procedure of application from the beginning, which could have unpredictable consequences for both countries.

Regarding the models of association between Kosovo and Albania up to the level of the international legal personality, as long as they will assist the process of integration of both countries into the EU, it can be expected that Brussels will not look at them with suspicion. On the contrary, the EU may even encourage them if Kosovo and Albania clarify that they do not intend to unify.

The Discussion of the Research of the Idea of Unification in Relation to International Considerations

The interviewees in this research, both, in Kosovo and Albania, were divided regarding the idea of unification of the two countries. Furthermore, this idea was rightly characterized as abstract and discussed superficially,[30] one that in both countries has remained a far-off dream in public discourse.[31]

In this respect, some from the interviewees think that populations of both countries have looked at themselves as temporarily divided as a consequence of a mistake of the international politics, namely, of the Conference of Ambassadors of London (1913). Furthermore, they consider that the major obstacle for attaining unification is non-achievement of a final agreement between Kosovo and Serbia,[32] whereas the contractual obligations towards NATO and EU are not considered as insuperable obstacles for the unification of two countries.[33]

From this point of view, it is argued that the will for unification of a nation cannot be impeded by International Law, having in mind that according to the advisory opinion of the International Court of Justice, the independence of Kosovo does not contradict the International Law.[34] In this regard, a distinct approach by some from the interviewees related to the idea of unification is that this will become an imperative, if the membership into the UN, NATO, and the EU will be rendered impossible for Kosovo.[35]

On the other hand, this approach is, however, considered as a use of this idea for blackmailing and intimidating the EU, given that unification of the two countries is considered to be a result of the success of Kosovo’s statehood.[36]

Regarding regional implications of unification of the two countries, it is argued that it will not have any noted consequences, given that unification will improve the peace and security in the Balkans.[37] Aside from the case of Republika Srpska, international actors may support unification as a means to promote long-term stability and security.[38]

In contrast to these established viewpoints, other interviewees argue that no unilateral steps should be undertaken in this direction[39] given that it would be impossible to achieve unification in this way.[40] Additionally, this could simultaneously endanger the membership of Albania in NATO, as well as present a risk for the return of the Resolution 1244 (1999) of the Security Council of the UN, which will damage heavily the process of integration of both countries into the EU as well.[41]

Despite of the fact that the most efficient way of unification is the absorption of Kosovo by Albania through the principle of moving borders, in which case Albania could remain member of international organizations and uphold its international agreements,[42] it is clear that this cannot happen in any way as a decision of only two countries, and without international support.[43]

On the other hand, the argument is raised of the existence of two factors that cannot co-exist with the idea of the state of Kosovo.[44] Firstly, of Serbian ethno-nationalism, which has the existence of the independent and sovereign state of Kosovo as an essential problem, and, secondly, of the Albanian ethno-nationalism, which sees Kosovo as a temporary creation until its unification with Albania.[45] In this line of argument, it is stressed that the best way towards de facto unification of two countries is within the European Union and NATO[46] This is supported by the fact that Kosovo was built as a state based on the principle of non-unification with other countries.[47] Moreover, it is considered that this idea cannot have as its reference the case of the German unification,[48] and, in the current situation, when Kosovo has a limited international legitimacy, the unification of the two countries can be perceived as a camouflaged “a la Crimea” unification.[49]

In addition, some of the interviewees consider that unification within the EU and unification in a single state are complementary.[50] According to them, the idea of unification is contradictory to the one of the integration in the EU given that the aspiration for integration in the EU would not have any meaning if at the same time the unification of the two countries is achieved.[51] Moreover, it is argued that Kosovo and Albania need a “Greater EU”, rather than “Greater Albania,” which will most probably be isolated and suffer from weak governance.[52] From this point of view, the unification of the two countries is seen as a realistic option only if the EU ceases to exist,[53] or if large changes occur in the international arena that would create circumstances supportive towards this idea.[54]

These interviewees also highlight the potential regional consequences of implementation this option, in which case an uncontrolled process of the re-drawing the maps of the Western Balkans might come into place,[55] given that this could open the so-called “Pandora’s Box” by crafting borders along ethnic lines.[56] Such a change of borders could affect Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia, Montenegro, and Greece,[57] which would cause a high regional instability,[58] by including here a possibility of the opening of the issue of Vorio-Epir by Athens.[59]

In the line of this argument, it is considered that the idea of unification should not be opened at all, since it will damage seriously both, Albania, and Kosovo,[60] bearing in mind that this idea is unacceptable for the key Western actors and for the regional geopolitics,[61] and also given that it paves the way for the return of the major influence of Russia in the Balkans.[62]

Conclusions

The above political-legal analysis highlights the arguments that if these two countries would move unilaterally, without full transatlantic consensus, either by absorption or merger of the two states, then this would have dire consequences for the statehood of Kosovo, and will dramatically damage the existential interests of Albania. In this case, Kosovo can quite easily loose its statehood, and this could simultaneously lead towards the imposition of sanctions by the United Nations, expulsion from NATO, and the blockade of the process of integration, or the full expulsion of Albania from the EU. In such circumstances, except of the fact that both, Kosovo and Albania, will be considered by the West as rogue states, Prishtina and Tirana would risk the vital interests of the West regarding the security and the stability of the region, including here the weakening of the cohesion of NATO and the EU.

Furthermore, it should be stressed that the idea of unification of Kosovo and Albania cannot be compared with the case of the German unification, and as such, in current circumstances, is in full collision with the idea of the enlargement of the EU and NATO, which is not based on the principle of the change of borders, but on the one of integration of states within the supra-national umbrella of Brussels. The pursue of the idea of unification by holders of institutions and political parties in both countries would create obstacles for their integration in the Euro-Atlantic institutions, as was noted on the occasion of the conditioning of Albania by Germany to give up from the ambitions for unification with Kosovo in relation with the negotiations for accession in the EU.[63]

On the other hand, the associational initiatives between Kosovo and Albania, which would not create a new subject of International Law, but will have instead integrative character between the two countries, and which will be in line with the European integrations, with the policies of NATO, and with cooperative regional initiatives, could even have the support of Brussels and Washington. However, a necessary precondition for such associational initiatives to be useful for both countries, and to be complementary, rather than in collision with the policies of the West in the region, is that they should be carried out in a transparent manner with political and civil actors in both countries.

Lulzim Peci is the Executive Director of Kosovo Institute for Policy Research and Development( KIPRED) based in Pristina, Republic of Kosovo. Lulzim Peci used to serve also as Ambassador of Kosovo in Stockholm (Dec. 2009 – June 2013

[2] James R. Crawford, The Creation of States in International Law, Second Edition, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2007, pg. 449.

[3] Ibid, pg. 477.

[4] Malcom N. Shaw, International Law, Sixth Edition, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2008, pg. 958.

[5] Vienna Convention on Succession of States in Respect of Treaties, Vienna, 23 August 1978. Entered into force on 6 November 1996. United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 1946, http://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/conventions/3_2_1978.pdf

[6] Vienna Convention on Succession of States in Respect of State Property, Archives and Debts, Vienna, 8 April 1983. (It has not entered into force yet), http://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/conventions/3_3_1983.pdf

[7] Malcom N. Shaw, International Law, Sixth Edition, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2008, pg. 963 – 964.

[8] See: James R. Crawford, The Creation of States in International Law, Second Edition, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2007, pg. 705.

[9] Malcolm R. Shaw, International Law, Sixth Edition, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2008, pg. 238-242.

[10] Ibid.

[11] The United Nations Charter, San Francisco, 1945, https://treaties.un.org/doc/publication/ctc/uncharter.pdf

[12] The Statute of the International Court of Justice, Article 36, https://www.icj-cij.org/en/statute

[13] See: North Atlantic Treaty, Washington D.C., April 4th, 1949, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/stock_publications/20120822_nato_treaty_en_light_2009.pdf

[14] Italy and Portugal, as founding countries of NATO, were not members of the UN until the end of the year 1955, meanwhile, the Western Germany, which joined NATO in the year 1954, was not member of the UN until the year 1973.

[15] See, for instance, Stefan Oeter, German Unification and State Succession, Heidelberg Journal of International Law, Heidelberg: Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law, 1991; Frans G. von der Dunk and Peter H. Kooijmans, The Unification of Germany and International Law, Michigan Journal of International Law, Michigan: Spring 1991; and, Michael Cox and Steven Hurst, “His finest hour: George Bush and the Diplomacy of German Unification”, Diplomacy & Statecraft, London: Frank Cass, Vol. 13, No. 4, December 2002.

[16] The Unification Treaty between the FRG and the GDR (Berlin, 31 August 1990), signed by Wolfgang Schäuble, Interior Minister of the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG), and Günther Krause, Junior Minister to Lothar de Maizière, Prime Minister of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) https://www.cvce.eu/content/publication/1997/10/13/2c391661-db4e-42e5-84f7-bd86108c0b9c/publishable_en.pdf

[17] For further research, see: Michael Cox and Steven Hurst, “His finest hour: George Bush and the Diplomacy of German Unification”, Diplomacy & Statecraft, London: Frank Cass, Vol. 13, No. 4, December 2002.

[18] Final Communique: Meeting of the North Atlantic Council at the Level of Foreign Ministers, 7–8 June 1990, point 15, https://www.nato.int/cps/su/natohq/official_texts_23696.htm?selectedLocale=en

[19] See, for instance, Romanian Parliament says would back Reunification with Moldova, Reuters, March, 27th, 2018 https://www.reuters.com/article/us-romania-moldova/romanian-parliament-says-would-back-reunification-with-moldova-idUSKBN1H32CS. Moldova had joined the the Romanian Kingdon in the year 1918, but it was annexed by the Soviet Union in the year 1940.

[20] See, for instance: Can NATO Members Kick Turkey Out of the Military Alliance?, Haaretz, October 16, 2019, https://www.haaretz.com/middle-east-news/turkey/can-nato-members-kick-turkey-out-of-the-military-alliance-1.7993968

[21] Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, Vienna, 23 May 1969, Entered into force on 27 January 1980, http://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/conventions/1_1_1969.pdf

[22] See, for instance, the analysis on the suspension or discontinuation of the membership of Turkey in NATO: Aurel Sari, Can Turkey be Expelled from NATO? It’s Legally Possible, Whether or Not Politically Prudent, Just Security, New York: Reiss Center of Law, New York University School of Law, October 15, 2019, https://www.justsecurity.org/66574/can-turkey-be-expelled-from-nato/

[23] See: Article 3. North-Atlantic Treaty: North Atlantic Treaty, Washington D.C., April 4th, 1949, https://www.nato.int/nato_static_fl2014/assets/pdf/stock_publications/20120822_nato_treaty_en_light_2009.pdf

[24] See the consolidated text of the Treaties of the European Union amended by the Treaty of Lisbon, https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/228848/7310.pdf

[25] See: EC: Albania and North Macedonia to open the negotiations, European Western Balkans, 29 May, 2019, https://europeanwesternbalkans.com/2019/05/29/ec-albania-north-macedonia-open-negotiations/

[26] For details see, for instance, EU blocks Albania and North Macedonia membership bids, BBC News, October 18, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-50100201

[27] The Stabilization Association Agreement between the EU and Kosovo, http://data.consilium.europa.eu/doc/document/ST-10728-2015-REV-1/en/pdf

[28] Article 7, The European Union Treaty.

[29] Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, Vienna, 23 May 1969, Entered into force on 27 January 1980, http://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/conventions/1_1_1969.pdf

[30] Interview with Robert Muharremi, Professor at the American University in Kosovo (AUK), Prishtina, June 4th, 2019.

[31] Interview with Jakup Krasniqi, President of the National Council of the Socialdemocratic Initiative, and former President of the Kosovo Assembly, Prishtina, June 11th, 2019.

[32] Interview with Arian Starova, former Foreign Minister of Albania, Tirana, September 2nd, 2019, and with Valon Murati, President of the Movement for Unification, Prishtina, June 19th, 2019.

[33] Interview with Bekim Çollaku, Chief of the Cabinet of President of Kosovo, and former Minister for European Integrations, Prishtina, June 12th, 2019, with Arian Starova, former Foreign Minister of Albania, Tirana, September 2nd, 2019, with Zef Preci, the Albanian Center for Economic Research, Executive Director, Tirana, September 11th, 2019, and with Valon Murati, President of the Movement for Unification, Prishtina, June 19th, 2019.

[34] Interview with Jakup Krasniqi, President of the National Council of the Socialdemocratic Initiative, and the former President of the Kosovo Assembly, Prishtina, June 11th, 2019.

[35] Interview with Bekim Çollaku, Chief of the Cabinet of President of Kosovo, and former Minister for European Integrations, Prishtina, June 12th, 2019, and with Sotiraq Hroni, the Institute for Democracy and Mediation, Executive Director, Tirana, September 3d, 2019.

[36] Interview with Albin Kurti, President of the Vetëvendosje Movement, Prishtina, June 10th, 2019.

[37] Interview with Jakup Krasniqi, President of the National Council of the Socialdemocratic Initiative, and the former President of the Kosovo Assembly, Prishtina, June 11th, 2019.

[38] Interview with Arian Starova, former Foreign Minister of Albania, Tirana, September 2d, 2019.

[39] Interview with Agron Bajrami, Editor in Chief of Koha Ditore, Prishtina, June 10th, 2019, and with Valon Murati, President of the Movement for Unification, Prishtina, June 19th, 2019.

[40] Interview with Visar Ymeri, Vice President of the Social Democratic Party, Prishtina, June 20th, 2019.

[41] Interview with Hajredin Kuçi, Vice President of the Democratic Party of Kosovo, and former Deputy Prime Minister of Kosovo, Prishtina, May 27th, 2019.

[42] Interview with Robert Muharremi, Professor at the American University in Kosovo (AUK), Prishtina, June 4th, 2019.

[43] Interview with Gazmend Oketa, former Deputy Prime Minister, Tirana, June 6th, 2019, and with Ilir Kalemaj, Vice Rector of the Department of Social Sciences, University of New York in Tirana, Tirana, July 15th, 2019.

[44] Interview with Arben Hajrullahu, Professor at the University of Prishtina, May 28th, 2019.

[45] Similar opinions has also Nexhmedin Spahiu, Professor at the AAB College, Interview, Mitrovica, July 1st, 2019.

[46] Interview with Përparim Kabo, Professor at the Mediteranian University, Tirana, September 9th, 2019.

[47] Interview with Remzi Lani, The Albanian Institute of Media, Executive Director, Tirana, September 2d, 2019.

[48] Interview with Arben Hajrullahu, Professor at the University of Prishtina, May 28th, 2019.

[49] Interview with Enver Hasani, Professor at the University of Prishtina, and former President of the Constitutional Court of the Republic of Kosovo, June 10th, 2019.

[50] Interview with Genc Ruli, former Minister of Finances, Tirana, September 15th, 2019, and with Zef Preci, the Albanian Center for Economic Research, Executive Director, Tirana, September 11th, 2019.

[51] Interview with Tonin Gjuraj, Professor, European University of Tirana, Tirana, September 2d, 2019.

[52] Interview with Arta Dade, former Minister of Foreign Affairs, Tirana, September 16th, 2019.

[53] Interview with Marko Bello, Deputy at the Albanian Assembly, Tirana, September 2d, 2019.

[54] Interview with Jetlir Zyberaj, Advisor to the Foreign Minister of Kosovo, Tirana, June 21st, 2019.

[55] Interview with Aldo Bumçi, former Minister of Justice, Tirana, September 3d, 2019.

[56] Interview with Jetlir Zyberaj, Advisor to the Foreign Minister of Kosovo, Tirana, June 21st, 2019.

[57] Interview with Dalibor Jevtić, Deputy Prime Minister of Kosovo, Prishtina, June 11th, 2019, with Miodrag Milićević, NGO Aktiv, Executive Director, Prishtina, June 25th, 2019, and with Rada Trajković, former deputy at the Kosovo Assembly, Prishtina, June 8th, 2019.

[58] Interview with Rada Trajković, former deputy at the Kosovo Assembly, Prishtina, June 8th, 2019.

[59] Interview with Enver Hasani, Professor at the University of Prishtina, and former President of the Constitutional Court of the Republic of Kosovo, June 10th, 2019.

[60] Interview with Mimi Kodheli, former Minister of Defense, Tirana, September 4th, 2019.

[61] Interview with Ferdinand Gjana, Rector of the University College Beder, Tirana, September 3d, 2019.

[62] Interview with Fatmir Mediu, former Minister of Defense, September 2d, 2019.

[63] Berlin warns Tirana: Forget ambitions for Greater Albania (Προειδοποίηση Βερολίνου σε Τίρανα: Ξεχάστε τις φιλοδοξίες για «Μεγάλη Αλβανία»), Skai, 26 September, 2019: https://www.skai.gr/news/world/proeidopoiisi-verolinou-se-tirana-ksexaste-tis-filodoksies-gia-megali-alvania.