ADEA GAFURI

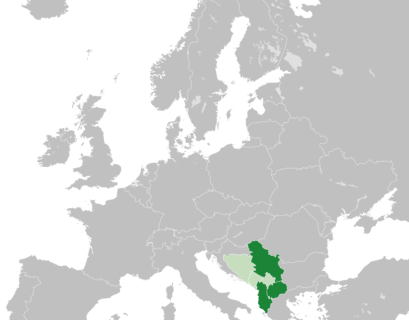

The Western Balkans Six Western Balkans Six (WB6/WB) Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Montenegro, Kosovo, North Macedonia (NM), and Serbia have been recipients of EU democracy assistance for more than three decades. The European Union is heavily involved in the political processes of these countries, not the least because these countries are also on the accession pipeline. To date, all the countries are stuck in the hybrid status and a political landscape dominated by corrupt strongmen, democratic erosions and illiberal practices. Despite the EU’s substantial support and democracy assistance, WB6 have been experiencing serious backsliding in democratic components for over a decade. What’s more in the recent decade, the role of China and Russia is pushing back the democratic establishment and compliance with the EU standards. Here, I argue that the role of China and Russia inadvertently diminishes further the role of the EU and the US in furthering democratic norms in the region.

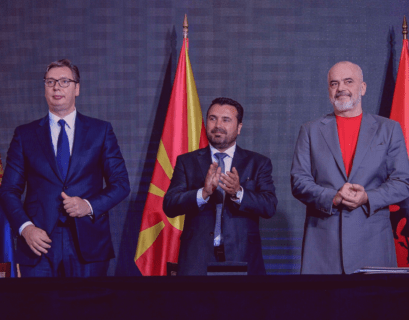

While Western Balkan countries have proceeded gradually in the EU membership, they have not improved democratic conditions. In contrary, while proceeding in accession criteria, the region, has experienced democratic erosions.[1] Moreover, several authors argue that the EU’s successful use of political conditionality in aspiring member countries has reduced following the enlargement of 2004 and 2007. In the case of the Western Balkan countries, the EU’s support has allowed leaders with undemocratic tendencies to strengthen their power and entrench informal networks. This is the case of Vucic in Serbia, Djukanovic in Montenegro, Rama in Albania.[2] Even though, among WB6 Serbia and Montenegro are frontrunners in the EU accession process to date they are both considered electoral autocracies.[3]

On the other hand, the European Union’s has not been able to maintain a credible commitment perspective and involvement with the WB. In the words of Professor Florian Bieber “The European Union has been invisible, slow and undecided.“ Notably, the lack of unity between EU member countries toward Western Balkans future has sent mixed signals to the people and WB6 leaders. To begin with, the lack of EU presence during Serbia’s elections in June 2020 which were one of the most fraudulent elections in Serbia’s history.[4]The invisibility of the EU in Montenegro during protests against church law and the August 2020 elections that witnessed the victory of several parties including the Serbian nationalist party, but also marked an end to Djukanovic’s “one-man rule” for the first time in more than three decades. The slowness of the EU to act as a meditator on the normalization of Kosovo-Serbia relations, that led to the involvement of the US with a vague and highly politicized economic agreement which could pave the way for more problems than solutions in the future. The lack of a clear path for BiH accession path and last but not least, the delay of accession negotiation for North Macedonia and Albania despite their fulfilment of criteria’s – mainly due to the lack of unity inside the EU, has left the region confused and hopeless to maintain a credible EU accession prospect. This, in turn, has created grounds for actors like China and Russia to gain traction and instrumentalize the lack of economic development, weak democratic institutions and in some cases exacerbate ethnic divisions to push their policies.

When the EU and the US have watered down their commitment to the region, Beijing and Moscow have gained momentum by offering quick solutions without conditionality for democratic reforms. China and Russia when offering financial support do not require that WB member states reform their state enterprises, rule of law or ousting of the corrupted officials. On the contrary, they prefer top-down, state-led, leader to leader agreements. More often than not, with agreements signed behind closed doors without providing transparency to the public, facilitating the already prevalent grand corruption at the highest levels of elites, which haunts every country in the region.

Small, developing, economically unstable countries dominated with rife corruption give opportunity to powerful actors like China and Russia to acquire influence. Moreover, russian elites have overtly announced that they are not hesitant to support self-interested groups against western international influence.[5] This is shown in the case of Russian support to Macedonian Revolutionary Organisation (VMRO) one of the most corrupt and scandalous parties in Macedonia’s history; the separatist group in Bosnia – the Republika Srpska; the support of Serbian autocratic strongman Aleksandar Vučić and even leading a coup attack in Montenegro in 2016.

Strikingly, China has included WB6 countries into one of its largest investment frameworks worldwide – the Chinese Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). WB countries excluding Kosovo are part of the China-Central Eastern Europe Cooperation Forum, 17 + 1 with Greece as the last participant included in this project.[6] Important to note, compared to other Central and Eastern European countries and other EU members, the capacities in the region are on average are much lower when it comes to transport infrastructure – railways, highways and energy production.[7] This initiative will fill some of these gaps in transport and infrastructure.

The WB region is geostrategically important for China to deepen its influence on the European continent and their involvement with the EU markets. This project is a bridge that connects the Chinese road with the port of Piraeus in Greece (owned by Chinese Companies 67%) which means access to the Mediterranean Sea and other markets in the EU. For Central, Eastern and Southeastern European countries between 2007-2017 the investment loans amounted up to 12.2 bn EUR. In Serbia alone, China has invested 1 billion euros mostly loans, to develop infrastructure and energy projects. In terms of cooperation, Serbia remains the key partner of China in the region. Also, Serbia considered by V-Dem Report 2020 an electoral autocracy is currently among the top ten autocratizing countries worldwide.[8]Over the past year, Serbia has increased media censorship, violations of civil rights and freedoms, and election irregularities and fraudulence have become more prevalent.

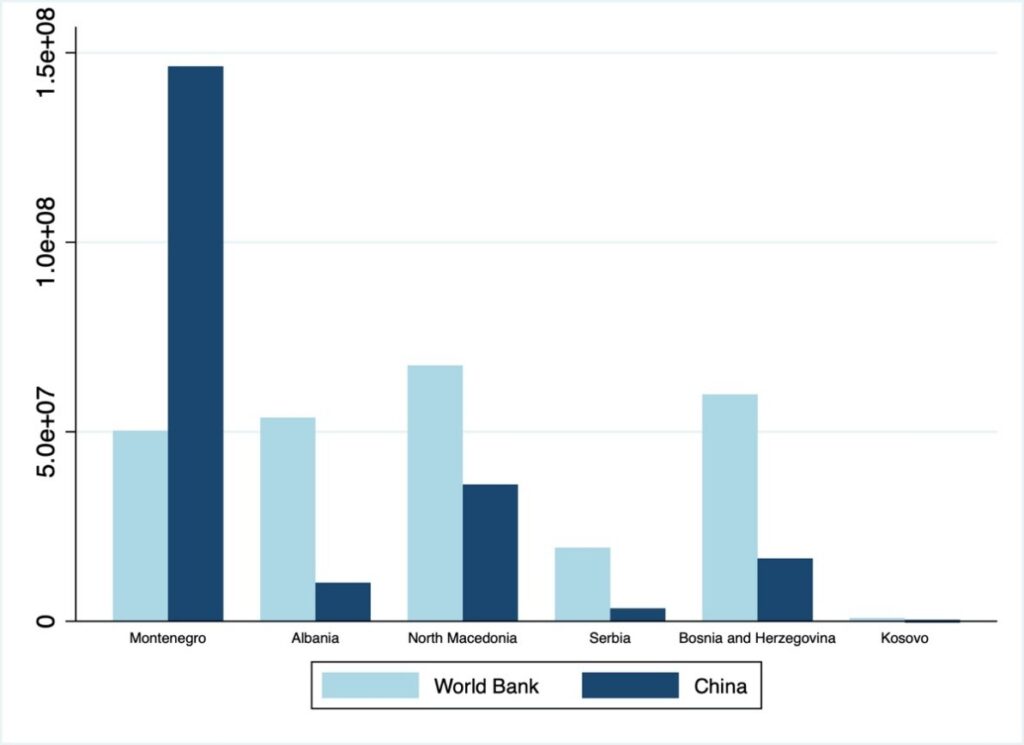

Figure 1: Comparing World Bank and Chinese Financial Flows by Country per population (Data: GeoQuery AidDATA)

Other countries including Bosnia and Herzegovina, North Macedonia, Montenegro and to a lesser extent Albania and Kosovo have also been targeted by Chinese financial flows. To illustrate, Figure 1 displays the amount of funds by the World Bank and China to WB countries by population. Compared to each country’s population, it is clear that Montenegro and North Macedonia have received largest sums. It is evident that in Serbia, Chinese funds still seem much smaller compared to World Bank funds. On the other hand, in the case of Montenegro, the amount of Chinese investment exceeds the initiatives of the World Bank. As Montenegro hosts only one Chinese infrastructure project yet it is the largest and most ambitious project in the Western Balkans.[9]

An important point of contention between international actors in the region is Kosovo’s statehood. Kosovo’s independence in 2008 is supported by both the EU (as an institution) and the US while it is strongly opposed by Russia, China and Serbia. China recognizes Kosovo as part of Serbia, citing this as the main point of the “Sino-Serbian” partnership. Thus, China and Russia’s support of Serbia in Kosovo-Serbia conflict and this shared anti-Western sentiment, remain the foundation of the partnership with Serbia. To boost, president Vucic has consistently leveraged their support to undermine democratic institutions, strengthen his grip of power, much like Chinese and Russian styles of governance. Although, president Vucic has been good at maintaining a pro-European facade, praising democratic values and using pro-European rhetoric while doing the opposite. And so, China and Russia’s support to autocratic leaders has by far paved the way for more autocratic practices and also contributed to increasing tensions between ethnic groups.

Moreover, in the Western Balkan countries, Chinese-led initiatives do not prioritize strict measures for clean and environmentally friendly projects. Two accidents that showed that lack of environmental measures are the calamity of Tara river in Montenegro, with soil and chemical waste released into the river caused by the construction project led by China. Also, the hazardous accident with black powder smoke from the steel power plant in Smederevo river port in Belgrade, owned by China’s Heibei Iron & Steel Group.[10] Both incidents related to China led the regional project “Road and Bridge Corporation” initiative. Several activists have called them “ecological terrorism.” These incidents not only offer quick and risky solutions that pose multiple problems but also further the alignment with the EU standards and procedures. As a result, these unsafe infrastructures posing environmental hazards, further the divide between the WB and the EU standards and delay WB countries path towards meeting the conditions for the EU accession.

Among the main issues of concern is that Chinese investments are mainly based on loans rather than financial aid. As in the case of African countries, which have been the target of Chinese investment and are considered among the fastest-growing economies in the world, their debt burden has soared. Moreover, with the current economic crisis brought by Covid19 pandemic, these countries are already seeking debt relief as they are unable to pay. To some, the Chinese investment approach has been coined as “Debt Trap Diplomacy,” – an attempt to attract poor countries with small emerging economies, which in reality can never pay back.[11]Additionally, China’s investments are bestowed upon with higher interests’ rates and shorter repayment schedules as compared to loans from the World Bank or Asian Development Bank. Montenegro’s government borrowed from China €1.3bn, this huge amount of debt for such a small country has increased its GDP-to-debt ratio to 80 percent.[12] MNE could fall into the “debt trap” similar to the case of Sri Lanka – which was forced to lease one of its port to China.[13]To make matters worse, with this high percentage of debt Montenegro cannot enter the EU.

While the EU is the largest donor in the region, few people in the region are aware that the EU granted around 3.3 billion dollars as a recovery package during COVID19 crisis. Meanwhile, China sent medical equipment help and only 6 doctors to Belgrade. The President of Serbia – Aleksander Vucic greeted them in person and kissed the Chinese flag. This gesture marked Serbia’s participation in “mask diplomacy.”[14] On the other hand, the EU’s inability to voice its efforts and the large assistance they give to these countries has overshadowed their endeavours in the eyes of citizens in WB. Whereas, Chinese counterparts ostentatiously show their assistance, making citizens more susceptible to think that China is more ready to assist in times of crisis than other Western donors.

In the words of the senior fellow for political and security affairs at the National Bureau of Asian Research, Nadège Rolland “It is not so much the physical manifestation (roads and railways) of the Belt and Road Projects, it’s about the intangible outcomes, people- to -people exchanges, elite capture, the formation of future elites, penetration of universities, changing the minds of the journalists. Investments are just a tool to open doors and entice other parties to cooperate with China, to create a community that respects China’s interest, doesn’t criticise its activities and abides by China’s rules.” [15]

While China’s influence in the region is largely based on economic ties, Russia’s influence rests on ethnological and political connections. Their approaches although different, they complement each other. Both China and Russia undermine democratic values and support for strongmen whose past is marred with corruption scandals, nationalist movements, share anti-Western ideals in the region and provide financial support unconditional on democratic progress.

On the other hand, Russia provides support to the orthodox church and religious communities in Serbia, BiH, and Montenegro and North Macedonia. However, Moscow’s interference is limited in Albania and almost none in Kosovo, which Russia strongly rejects as an independent country.

Russian intervention is felt mainly through the widespread Russian media in the region, support for Serb nationalist communities and the Serbian Orthodox Church, the supply of weapons to ethnic groups, and siding with nationalist and often undemocratic leaders.

Russia’s biggest ally in the region is Serbia, as they enjoy deep cultural and political ties. Moscow is also the biggest supporter of Belgrade’s stance on Kosovo-Serbia conflict. For several years now, Serbia has been reluctant to make any concession in the EU and US-led Kosovo- Serbia negotiations, if it jeopardizes its relation with Russia.[16] According to Gallup International poll, Putin is the most popular leader in Serbia, and 47% of respondents are convinced that Russia provides the largest amount of aid to Serbia.[17] While in fact, the EU and the US provide 90% of foreign aid to Serbia.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, a country already divided along ethnoreligious lines, Croatians and Bosniak entities follow a pro-Western policy. In fact, Serbian counterparts “Republika Srpska” led by Dodik receive direct support and assistance from Serbian and Russian leaders. Moscow’s support to the Serbian entity, hinders BiH accession to EU and NATO membership. Moreover, although Dodik-led Republika Srpska does not have an army, Russia donated weapons and training troops to their special branch of force, rising the tensions in the country. As a consequence, of Russia’s of the Serbian ethnic group in an already divided society encourages further fragmentation of existing divisions and destabilization of the country, which may have a spill-over effect on other existing conflicts in the region.

On the other hand, relations between Russia and Montenegro and North Macedonia are rather bitter. Both countries accuse Russia of interfering in their domestic political landscape. In 2016, the Montenegrin government accused Russia of launching a coup attack in cooperation with the opposition parties, to overthrow the MNE government and prevent NATO membership. Nevertheless, Montenegro eventually joined NATO in 2017. In Montenegro, Serbian Orthodox Church is the largest religious institutions attempting to position itself among key political players, also backed heavily by Russian. To date, Russia continues to support the Serbian nationalist party supported by the Serbian Orthodox Church, in forming a new government and ousting the ruling pro-Western party which held power for 30 years. Although we have yet to see the formation of a government after the August 2020 elections, it is likely that Russian and Serbian influence will dominate and anti-Western sentiments will rise.

In the case of Northern Macedonia, the Russian government is suspected of interfering in the referendum in 2018 on the name issue with Greece. Western diplomats claimed that Russia led a boycott campaign on Facebook. People would see up to forty posts a day in their feed with the text “Are you going to let Albanians change your name”? an attempt to increase the tension among ethnic minorities in the country.[18] The results of the referendum results supported the Russian position and the turnout was very low. However, the Macedonian government pushed the name change through the parliamentary vote, which eventually paved the way for NATO accession and proceeding with EU accession criteria.

What does it Mean for the State of Democracy?

Foreign aid and direct investment are not in themselves a threat to the already weak democratic regimes in the Western Balkans. These provide opportunities for the WB to meet its demands and develop a modern infrastructure, high-speed rail, modern ports. What is troubling are the intended and unintended consequences of China’s and Russia’s support of undemocratic leaders, ethnic and religious groups, media censorship, surveillance, data collection breaches, the spread of control and misinformation which are likely to hamper the development of fragile institutions of these countries.

While it remains to be analyzed how foreign powers influence citizens’ perception of democratic values in the region, recent polls show that support for Russia in Serbia has increased by 20% and China is viewed more positively than the EU and U.S.[19] Existing literature on democratization highlights that citizens’ perception and support for democratic structures is essential for the establishment and consolidation of democratic regimes.

One the other hand the EU has given priority to stability, conflict resolution and has made secondary democratic reforms.[20] This has enabled autocratic leaders to strengthen their grip of power and rely on the EU as an external source of legitimation. Despite, the European Union’s deep involvement in the region with EU membership prospect, conditionality reforms and democracy aid programs the region has experienced democratic erosions. Although, countries of the Western Balkans have never fully democratized, and these erosions have occurred against the backdrop of fragile democratic institutions.[21]

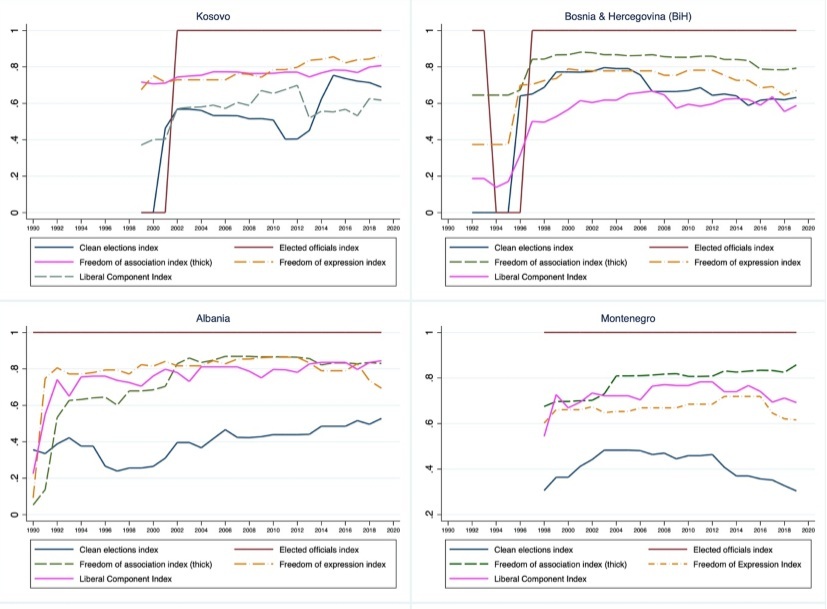

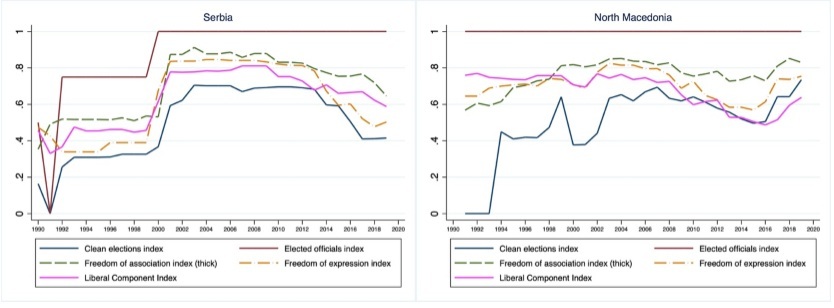

The main impediments to democratic progress in WB countries are attacks on media freedoms, election irregularities and the overlap of the executive, judiciary and legislative branches (see figure 3 for more details). Other indicators which are not directly related to democracy, that are widespread and impact largely the democratic institutional qualities include grand corruption, clientelistic networks, ethnic and religious divisions, polarization, unresolved conflicts from the past and the interference of undemocratic foreign powers.

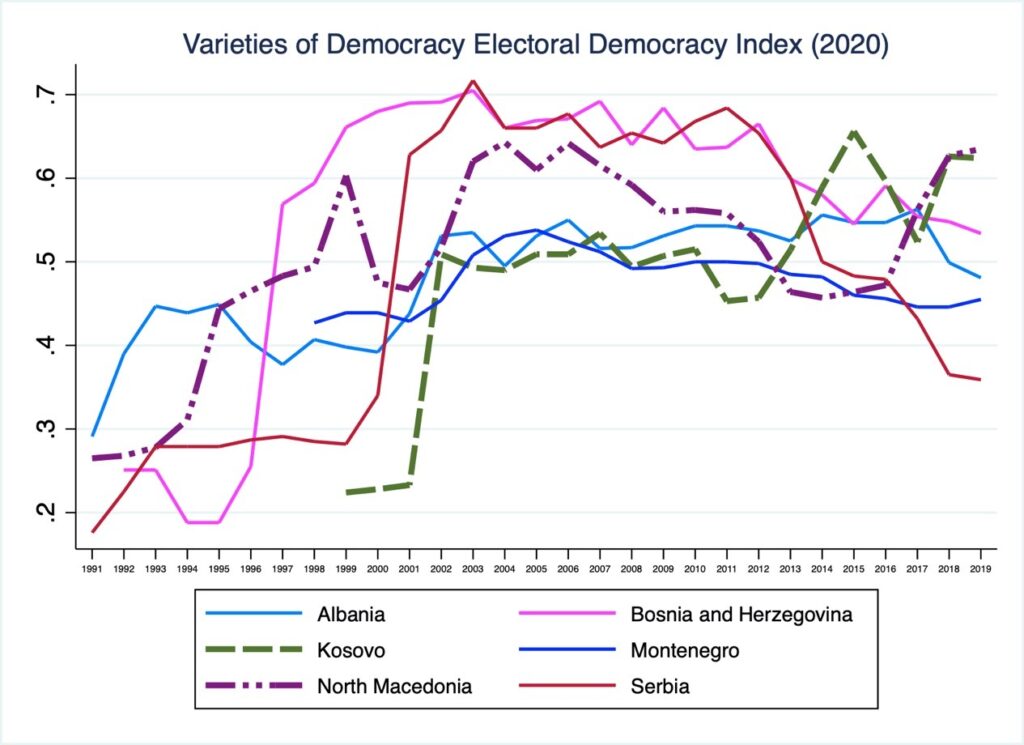

Figure 2: Electoral Democracy Index for each country, 1990-2019.

Figure 2 shows that almost every country has experienced democratic erosion, besides North Macedonia and Kosovo, I give a brief overview below. For specific democracy indicators for each country, please check Figure 3.

To start with, democracy in Serbia has struggled since Aleksandar Vučić came to power. First as deputy minister, then as prime minister and finally as president, he has steadily strengthened his control over the executive, the judiciary, the security services and all media outlets. While one of the most advanced countries in EU membership project, to this day Serbia has not only become more autocratic over the years but is also currently among the leading countries in the world that experienced major human rights violations and restrictions on democratic freedom during the Covid19 pandemic.

The government of Montenegro ruled by a pro-Western leader for more than three decades coined as “one-man” rule has experienced regression in democratic qualities with issues related to judicial institutions and scandals undermining public trust, high profile corruption and deep political and societal cleavages. The results of Montenegro’s election in August 2020 marked an end to Djukanovic’s rule. However, a new government is likely to form between opposition parties that include a radical right-wing party that is pro-Serbian and pro-Russian and could potentially destabilize the whole region.

On the other hand, Kosovo’s institutions suffer from informal international intervention, contested pluralism within the country, endemic corruption, state capture, and almost a failed judiciary system. Although several democracy indices have praised Kosovo’s election results and the forming of government from opposition-led coalitions and independence of media.[22]This was short-lived (less than two months) and the government was ousted through a no-confidence vote in parliament. Showing that state capture and political corruption are prevalent in almost every institution in the country.

The main impediments in Bosnia & Hercegovina are the complex decision-making procedures, ethnicity-based veto power, entrenched ethnic divisions and the rise of nationalistic populism. As well as support from international powers for certain ethnic groups like the Serb-majority Republika Srpska (RS), which trigger a constant political crisis. While, Albania an official candidate in EU accession is among the most corrupt countries in Europe dealing with massive organized crime issues, challenges to free media and low electoral integrity.

Lastly, North Macedonia is the only country that has shown progress first with the name change from “Republic of Macedonia” to “Republic of North Macedonia” paving the way to NATO accession and EU membership. Over the past years, NM has improved its election quality, media independence, cooperation between government and civil society, however, high-profile corruption, judicial independence and state capture by partisan forces remain key issues.

It remains an empirical puzzle on how different actors in the region, who pursue opposing policies are impacting the process of democratization in these countries. By disregard of democratic values and empowering of certain political elites, the growing influence of non-democratic actors such as Russia, China and Turkey is likely to have an impact on WB countries ‘weak institutions, but also in altering citizens’ perceptions of democratic ideals. And, we have yet to see if the influence of different international actors will present new alternative models of governance and if democratization will remain the only aspiration in these countries.

Figure 3: V-Dem Indicators For Each Country, 1990-2019

Adea Gafuri is PhD candidate at the Department of Political Science at Gothenburg University. Sweden. She holds a master’s degree in Political Science from Sabanci University. Her main research interests include democratization, democracy, foreign aid, and political methodology. She works with quantitative and qualitative methods and previously has conducted fieldwork in the countries of the Western Balkans on EU integration and democracy assistance. She is also affiliated with the Varieties of Democracy Institute (V-Dem) at Gothenburg University.

[1] Adea Gafuri and Meltem Muftuler-Bac. “Caught between Stability and Democracy in the Western Balkans: A Comparative Analysis of Paths of Accession to the European Union.” East European Politics, 1–25, 2020.

[2] Richter Solveig and Natasha Wunsch. “Money, Power, Glory: the Linkages between EU Conditionality and State Capture in the Western Balkans.” Journal of European Public Policy 27:1, 41-62 .2020. DOI: 10.1080/13501763.2019.1578815

Florian Bieber. “The Rise of Authoritarianism in the Western Balkans.” Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020.

[3] Varieties of Democracy Report. 2020. “Autocratization Surges – Resistance Grows”

[4] Aleksandar Ivković. “Election Day in Serbia: Massive Irregularities Even without True Competition and Uncertainty,” European Western Balkans, 2020.

[5] Mark Galeotti. “Do the Western Balkans Face a Coming Russian Storm?,” ECFR, 2018. https://www.ecfr.eu/publications/summary/do_the_western_balkans_face_a_coming_russian_storm.

[6] “China’s Economic Footprint in the Western Balkans,” Bertlesmann Stiftung, 2020. https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/fileadmin/files/BSt/Publikationen/GrauePublikationen/asia-policy-brief-chinas-economic-footprint-in-the-western-balkans-28c4d775834edcc469f4f737664f79f932d6f9a1.pdf.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Varieties of Democracy Report. 2020. “Autocratization Surges – Resistance Grows– “ https://www.v-dem.net/media/filer_public/f0/5d/f05d46d8-626f-4b20-8e4e-53d4b134bfcb/democracy_report_2020_low.pdf.

[9] “China’s Economic Footprint in the Western Balkans,” 2020. https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/fileadmin/files/BSt/Publikationen/GrauePublikationen/asia-policy-brief-chinas-economic-footprint-in-the-western-balkans-28c4d775834edcc469f4f737664f79f932d6f9a1.pdf.

[10] Igor Todorović. “Protest Held in Serbia’s Smederevo against Pollution from China-Owned Steelworks,” 2020. https://balkangreenenergynews.com/protest-held-in-serbias-smederevo-against-pollution-from-china-owned-steelworks/.

[11] Austin Doehler. “How China Challenges the EU in the Western Balkans.” 2019. https://thediplomat.com/2019/09/how-china-challenges-the-eu-in-the-western-balkans/

[12] James Kynge and Valerie Hopkins. “Montenegro Fears China-Backed Highway Will Put It on Road to Ruin,” 2019. https://www-ft-com.newman.richmond.edu/content/d3d56d20-5a8d-11e9-9dde-7aedca0a081a.

[13] Due to Sri Lanka’s government inability to pay its debt to China, Sri Lanka was forced to allow China to take physical control of one of its port.

[14] Vesko Garcevic. “Russia and China Are Penetrating Balkans at West’s Expense,” 2020. https://balkaninsight.com/2020/08/18/russia-and-china-are-penetrating-balkans-at-wests-expense/.

[15] Nadège Rolland. “Presented at the Power 3.0 Podcast Episodes: The Evolution Of China’s Belt And Road: A Conversation With Nadège Rolland” 2019. https://www.power3point0.org/2019/01/08/the-evolution-of-chinas-belt-and-road-a-conversation-with-nadege-rolland/.

[16] Abdullah Keşvelioğlu. “European Union Challenged: Russia and China in the Western Balkans.” Accessed September 25, 2020. https://researchcentre.trtworld.com/publications/policy-outlook/european-union-challenged-russia-and-china-in-the-western-balkans.

[17] Snezana Bjelotomic. “The Pope and Merkel the Most Popular World Leaders; Putin ‘Wins’ in Serbia,” 2020. https://www.serbianmonitor.com/en/the-pope-and-merkel-the-most-popular-world-leaders-putin-wins-in-serbia/.

[18] Simon Tisdall. “Result of Macedonia’s Referendum Is Another Victory for Russia,” 2018. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/oct/01/result-of-macedonia-referendum-is-another-victory-for-russia.

[19] “Between East and West: Public Opinion & Media Disinformation in the Western Balkans.” National Democratic Institute, May 23, 2019. https://www.ndi.org/publications/between-east-and-west-public-opinion-media-disinformation-western-balkans.

[20]Marko Kmezić and Florian Bieber “The Crisis of Democracy in the Western Balkans. An Anatomy of Stabilitocracy and the Limits of EU Democracy Promotion”Balkans in Europe Policy Advisory Group. 2017.

Gafuri, Adea, and Meltem Muftuler-Bac. “Caught between Stability and Democracy in the Western Balkans: A Comparative Analysis of Paths of Accession to the European Union.” East European Politics, 1–25, 2020.

[21] Florian Bieber. “The Rise of Authoritarianism in the Western Balkans.” Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020.

[22] “Freedom in the World” Accessed 2020. from:https://freedomhouse.org/report/freedom-world.

Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, David Altman, Michael Bernhard, M. Steven Fish, Adam Glynn, Allen Hicken, Anna Luhrmann, Kyle L. Marquardt, Kelly McMann, Pamela Paxton, Daniel Pemstein, Brigitte Seim, Rachel Sigman, Svend-Erik Skaaning, Jeffrey Staton, Steven Wilson, Agnes Cornell, Nazifa Alizada, Lisa Gastaldi, Haakon Gjerløw, Garry Hindle, Nina Ilchenko, Laura Maxwell, Valeriya Mechkova, Juraj Medzihorsky, Johannes von Römer, Aksel Sundström, Eitan Tzelgov, Yi-ting Wang, Tore Wig, and Daniel Ziblatt. 2020. ”V-Dem [Country–Year/Country–Date] Dataset v10”. Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. https://doi.org/10.23696/vdemds20.