By Ilir Konomi

An Albanian legation in Washington

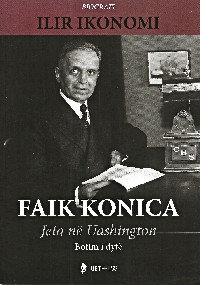

On July 11, 1926, a sturdy, handsome man by the name of Faik Bey Konitza arrived from Boston in Washington, D.C. where he was to serve as the diplomatic envoy of Ahmet Zogu’s Albania. His appointment as the first Albanian Minister to the U.S. had been several months in the making.

In April of that year, the office of President Calvin Coolidge received a letter signed by the Secretary of State Frank Kellogg. The letter stated that President Zogu wanted to open a legation in Washington and appoint Faik Bey Konitza as Minister Plenipotentiary to the United States.

“According to the information in the Department – the letter said – Mr. Konitza is distinctly friendly to this country where he has resided for a number of years. He is said to have received part of his education at Harvard University and to hold a degree from that institution. Our legation reports that he enjoys considerable influence in Albania where he is widely known, although he has held aloof from personal politics and has not identified himself with any political party. He has, however, represented his country at a number of international conferences and was prominent in the movements which led to the independence of Albania. I know of no reason Mr. Konitza should not be received by this Government and if you so desire I will instruct our Minister to inform the Albanian Government that the appointment will be acceptable.”[1]

On the opposite side of the ocean, Zogu was impatiently waiting for an answer. Thanks to Everett Sanders, Coolidge’s private secretary, things moved rather swiftly and the U.S. President gave his consent by writing “Done! Let him come!” at the upper left corner of Kellogg’s letter.

Konitza came to Washington’s diplomatic world from an Albanian environment, after five years as chairman of the Pan Albanian Federation Vatra in Boston. Vatra’s leaders held him in great esteem and revered him immensely. That veneration came mostly from the reputation as a scholar that he projected on Vatra, the largest and the most stable organization of the Albanians in America. None of Vatra’s leaders were as learned as he was. The only one who came close was Bishop Theophan Noli, who had his adherents among the Albanians of Boston. But Noli had left for Europe several years before, and was regularly being attacked as a “bolshevik” by Vatra’s newspaper Dielli, which until June 1926 was led personally by Konitza.

Faik Konitza’s appointment was viewed with suspicion by some Albanians. Those who harbored doubt said that he was seduced by Zogu’s money, something he denied categorically. “The salary of a Minister Plenipotentiary is very low” said a Dielli editorial that appeared to be written either by Konitza or with his instructions. “Therefore it cannot be said that he accepted the appointment because of material interest. Since 1914 various governments had offered him to serve as a diplomatic representative in Washington, London and Italy. He always rejected.” Then the editorial explains the reasons why he accepted Zog’s offer: “Mr. Faik Konitza believes the government (in Albania) must have the support of all good willing individuals to ensure stability within the nation and to preserve its honor without. He undertook the burden with the intention of helping in this patriotic endeavor. We believe that once the state is fully strengthened and the opposition has calmed down, Mr. Faik Konitza will ask the government to step aside in order to pursue a literary career.”

According to Konitza, Zogu’s Albania being too weak and surrounded by enemies, needed peace and disipline, unity inside and respect abroad. And he said Ahmet Zogu was the leader “capable of uniting and governing this divided and disobedient people.”[2]

The chief American diplomat in Tirana, Charles Hart, believed that patriotism, not money, was the main reason Faik Konitza accepted Zogu’s offer. In December 1925, when word had spread on the nomination Zog was about to make, Hart wrote to the State Department the following: “He (Konitza) has held aloof from personal politics, commiting himself at no time in favor of any Albanian administration. Instead of politician he is credited even among those he has opposed as preferring the novel position of patriot, a specimen which some observers vehemently declare is almost extinct among the so-called upper class Albanians.”[3]

Those who hated Konitza had their arguments ready. They criticized him for trying to disunite the Christian and Muslim Albanians of America. They claimed he believed in the violent overthrow of government, as he had publicly stated in Dielli when he expressed support for Noli’s revolution in June 1924. And this, they believed, ran contrary to the U.S. Constitution. They also claimed that when he first came to the U.S. and was asked by Immigration officials whether in the future he intended to become a U.S. citizen, he had replied “no.” They alleged he had tried to evade personal income taxes and had paid his dues only after being forced to do so.[4]

Just one week before leaving Boston, in an obvious attempt to reassure himself and put criticism to rest, Konitza explained in Dielli that every individual has inside oneself the yardstick with which to measure one’s own actions. “Measured against conscience, I know what others may not know, that my actions were both sincere and reasonable,” he wrote.[5]

Despite all the envy and the suspicions that the new appointment had generated, Konitza would not break his ties with Vatra and this was part of a gentleman agreement with President Zogu. From now on, he would be the honorary chairman of the organization.

It was clearly in the interest of the President of Albania to have Vatra on his side. Zogu did not want any propaganda against himself among the Albanians of America and this could be made possible by having Konitza in control of the Albanian immigrant community. The Department of State thought the same. A note by the Division of Near Eastern Affairs said that all political factions in Albania desire the support and approval of Vatra which indirectly enjoys great influence in the mother country. Therefore, it said, “the wish of the Albanian President to appoint Konitza as minister to the United States is very likely an attempt to ensure the political support of the Vatra Society.”[6]

On July 13, 1926, the Foreign Ministry in Tirana received a telegram in which Konitza informed his superiors that he had arrived in Washington and had left copies of the credentials at the State Department. He first settled at the Willard, a hotel where Mark Twain was said to have written two books and where the term lobbying was born.”[7] The Willard was located on the Pensylvannia Avenue and was a short walk away from the White House.

Since Albania had never had a legation in Washington, Konitza’s arrival was greeted with curiousity in the press. The Washington Post, The Sun, and a number of less important dailies reported on the new envoy, who was called Frank by his American friends. Some newspapers also printed his official photograph which showed a man with hair split in the middle and with expressive, piercing eyes. There was certainly no lack of interest in the capital’s social circles, especially among the young women who were just starting a career; Konitza happened to be unmarried and the demand for bachelor diplomats was great among hostesses. This Albanian minister “ought to be extremely appealing. He is dark, suave and in the interesting fourties,” a newswire report claimed. In fact, Konitza had just passed fifty but looked much younger in the photo.

The reporters would soon learn that Albania, an extremely poor country with practically no influence in international affairs, would be represented in the American capital by an erudite individual whose interests spanned from music and literature to ancient and modern history, fashion, painting, cooking, and so on. After having completed elementary school in Turkey and later being educated in France, he had received a degree from Harvard, one of America’s premier universities. His French was perfect but his ability to phrase in English was also superb. His speech was flavorful and had the distinct accent that prompts one to guess the interlocutor’s country of origin.

On August 19, 1926 Konitza settled in The Mayflower, a hotel that was dedicated the year before. A suite of rooms would serve both as a legation and as living quarters for the new Albanian minister. The Mayflower had begun to be referred to as The Grande Dame of Washington. Everyone agreed that the nickname fit it perfectly, for this was the most luxurious hotel in America and the second best address in town after the White House.

The Albanian government would pay Konitza a monthly salary of 120 dollars, almost as much as he was paid as chairman of Vatra. However, the government would cover for him the costly hotel suite as well as all other expenses, including the entertainment of guests, travel, and a secretary.[8]

For Konitza, The Mayflower was the ideal place to stay. The hotel, a short walk from both the White House and the State Department, was a meeting place for some of the most prominent people of America, high ranking politicians, rich businessmen and famous artists.[9] President Coolidge often went there for official meetings or to see old friends. Some renowned individuals had rented apartments in the hotel. Among them were Everett Sanders, the President’s secretary, William Jardine, Secretary of Agriculture, Senators Rice Means of Colorado and Samuel Shortridge of California and Fleming Newbold, president of The Evening Star, rival of The Washington Post.[10]

Konitza brought hundreds of books to the Mayflower. A talking-machine with a meter-long master’s-voice horn was visible by the fireplace in the drawing room. His collection of clocks, big and small, was displayed near the book shelves. A bit further was a saxophone he had brought from England. A portrait of President Zogu alongside a picture of a little girl with flowers in her hands greeted the guests from a small table facing the door.

Opening a legation in Washington by Ahmet Zogu was undoubtedly a costly diplomatic move for Albania, the distant country little known by the Americans.

The history of Albania’s diplomatic representation in the U.S. capital had begun in March 1920, before the country won recognition by America. On that month, Constantine C. Chekrezi, a 27-year old youth from the Albanian village of Ziçisht, presented the credentials signed by Prime Minister Sulejman Delvina and Foreign Minister Mehmet Konitza, Faik Konitza’s brother.[11] Chekrezi, a Harvard graduated historian and a former Dielli editor, acted as “Commissioner of Albania in the United States” and maintained contacts with the Department of State. His salary was paid by Vatra. He was a semi-official representative and his name was not included in the diplomatic list contained in the Blue Book of the State Department. Like Chekrezi, there were more than 20 other representatives from countries with which the United States had no diplomatic ties. They tried to win the attention of the State Department in the hope that their country could one day be recognized by official Washington.[12]

On October 23, 1920, the Albanian government, through a letter to President Woodrow Wilson, appointed Charles Telford Erickson, a U.S. citizen, as “extraordinary envoy and plenipotentiary minister,” as always, in a semi-official capacity. Erickson, a Christian missionary, knew Albania better than any other American and regarded it as his second homeland. Mehmet Konitza believed that Erickson, who in the Paris Peace Conference had helped a great deal on the question of Albania’s borders and mandate, could give the small nation a strong voice in Washington, which in turn could result in its recognition by the United States. A week after his arrival in Washington, Erickson received a telegram informing him that Albania had changed government, the opposition had come to power with a cabinet headed by Iljas Vrioni and that in the new circumstances he should not expect any funds. Erickson had not been paid anyway because the expectation was that Chekrezi would hand him over the account and the office. That had not happened, and Erickson was faced with a dilemma.[13] In any case, he remained in Washington and continued to represent Albania in his capacity as a private citizen. Erickson did not even have enough money to pay the apartment rent, but the generous landlord helped him with with a little room in the attic.[14] Chekrezi did not like Erickson’s appointment and complained that this episode had delayed the recognition of Albania by the U.S. He boasted that he had brought the issue of recognition almost to a conclusion and that the arrival of Erickson had caused an interruption in his communications with the Department of State. Soon, Erickson left for Europe and Chekrezi remained “commissioner”. During his brief stay in Washington, Erickson insisted in his reports for the State Department that it was time for the United States to recognize Albania. “There are thousands of American Albanians to whom America is almost as dear as their motherland and upon whom no other country has such a hold on their imagination and affection,” he wrote.[15]

There were numerous other calls for recognition. Among the most impressive was that of a 28-year-old officer in Tirana. He was the Interior Minister Ahmed Bej Zogu from the Zogolli clan of Mat. When approached by an Associated Press reporter, the handsome young man who stood above the crowd and was routinely called “the hero of Albania” told him: “If America recognizes us and sends a diplomatic representative to Albania, it will be the biggest boost Albania can have. It would be the greatest encouragement this country would receive. America, whose pages of history gleam with glorious deeds in the cause of human liberty, should recognize Albania, for it is a country which has suffered long centuries of serfdom and now, born again as a nation, wants to retain the liberty so long withheld.”[16]

On August 28, 1922, after many hesitations, the United States granted de jure recognition to Albania. This came after the State Department was beginning to realize that the monopoly of the Albanian oil was ending up in Italian and British hands, leaving the American companies behind. However, the recognition was not simply a result of cold calculations by the bureaucrats in Washington and it appears that the lure of oil was only one reason. Another important reason was to give “moral encouragement to the Albanian people in a critical phase of their struggle for independence.”[17] Maxwell Blake, the Commissioner in Albania, in a letter to the Secretary of State, Charles Hughes, stated that “the Albanians, in spite of grave difficulties, have given sufficient evidence of political stability.”[18]

In Boston, Faik Konitza, as chairman of Vatra, immediately thanked the Secretary of State. His telegram was sent “in the name of the Albanians residing in America, some of whom fought and shed their blood in the ranks of the American army.”[19]

Although the office of Chekrezi in the capital had been closed on April 1922,[20] he continued to act occasionally as a commissioner while teaching modern history at Washington’s National University.[21]

After that, for four full years, Albania held no representation in the U. S. capital. The country was going through difficult times. According to an American newspaper, “cabinets passed in and out of the government house like trains through a tunnel. Any man with a sufficient following of rifle bearers and a desire to be prime minister would quietly organize his forces, wait for a night of full moon, which to all Albanians is an omen of good fortune, and then proceed to unseat the prevailing cabinet.”[22]

An attempt to open diplomatic representation in Washington was made in 1922, after the establishment of diplomatic relations with the U. S. At the end of August of that year Mithat Frashëri was proposed for plenipotentiary minister.[23] Konitza reacted immediately from Boston. In a confidential letter to the State Department, he pleaded with the Americans in the name of Vatra not to accept the appointment. “France and Italy have both rejected him, when the Albanian government tried to appoint Mr. Mithat Frasheri first to Paris, and then to Rome,” insisted Konitza in the handwritten letter in Autumn 1922.[24] In a memo accompanying his letter, a State Department official wrote: “It is possible that Mr. Faik Konitza is disappointed at not being selected for the Washington post.”[25] In the end, Konitza had his way. In January 1923, Albania’s Foreign Ministry decided to indefinitely postpone Frasheri’s appoinment. The U.S. Minister in Tirana, Ulysses Grant-Smith wrote to the State Departament that for the peace of the Albanian Colony in the United States “it would seem just as well that Mr. Frashëri should definitely renounce his intention of representing his country in Washington since it appears that Faik Konitza, President of the Albanian Federation Vatra is openly opposed to him.”[26]

In July 1924, when a government led by Fan Noli was in power, Albania’s consul in New York, Abdul Sula, visited the State Department and inquired whether it would be difficult to get the American approval were the Albanian government to open a legation in Washington. He was told that such a request would be examined immediately and that the State Department would be pleased to see an Albanian legation on the American soil.[27] However Noli had no time for legation. In December 1924, a brief uprising that brought the Bishop to premiership came to an end and Ahmed Zogu returned to power with the help of the Yugoslavs.

It was financially impossible for the new government to maintain many legations abroad. But Zogu, who regarded the United States as a future ally that could help him establish order and consolidate power, decided that opening a diplomatic representation in Washington should come without delay. The candidate for the new position had to be a learned Albanian, possibly a good speaker of English and a person who had strong ties with the Albanian community in America.

In January 1925, when he had just become prime minister, Zogu asked the acting Albanian consul in New York, Koço Tashko, to travel to Washington and contact the State Department to see what the U. S. Administration thought of the new Albanian government. Tashko told the officials that the Albanians had preferred the mountain man (Zogu) to the Harvard man (Noli), adding that it would be rather difficult for Zogu to find anyone to represent him in the U. S. since “the Vatra Society had in the past been hostile to the Ahmed Zogu faction and that such a powerful Albanian as Faik Konitza had also been in the opposition.”[28] However, things evolved rapidly. In a little more than a year, it was no other than Faik Konitza, formerly a bitter enemy of Zogu who was installed as plenipotentiary minister.

On July 16, 1926 the new Albanian Minister was received at the State Department by Secretary Kellogg, a small man with grey, glassy eyes. This was mostly a get acquainted session without much substance. They spoke about things that lay ahead, mainly a number of treaties to be signed between the two countries. The State Department had detailed information about Albania, thanks to the long cables it received from Charles Hart, the head of the Albanian mission in Tirana. In April of that year, Hart related that in Albania, there was nothing left from the republican atmosphere and that the regime was becoming monarchic.[29] In foreign relations, the pressure of the Italians on Zogu had substantially increased to the point that they had demanded Albania to become a protectorate, based on a decision of the Ambassadors Conference on November 9, 1921.[30] Obviously, the United States was too far away and uninterested in those developments.

On October 8, 1926, Konitza presented his credentials to President Coolidge in the White House. The ceremony took place in the blue room, an oval shaped space where the Presidents received their guests. “I consider myself fortunate in having the distinction of being the first Envoy of Albania to the great American Nation, a Nation I have long ago learned to love and to respect, and whose glorious history and wonderful achievements are sincerely admired by the Albanian people,” Konitza told the President.[31]

Coolidge, who had a reputation as a timid and modest president, replied that he appreciated the comment on the American nation and on the feelings cherished by the Albanian people for America. At the end, he wished Konitza a pleasant stay in Washington and the two men shook hands. For the President, the brief ceremony was nothing more than a routine required by the protocol. For Konitza however, it was a rare occasion in which a U. S. president was meeting face to face with a diplomatic representative of Albania, a nation whose very existence had been in question for a long time.

After the Credentials, one important act of Konitza in Washington was to visit the grave of the late President Woodrow Wilson, who was regarded as a hero by the Albanians. Wilson had died in 1924, four years after the Paris Peace Conference, where some of his actions had been critical in staving off the dismemberment of Albania among its neighbors. In Albania he was highly regarded by those who knew history. Among the common Albanians, his actions were not totally unknown either. The name Vilson or its version Yllson, had started to become popular in the Albanian towns.[32] In 1921, professor Elmer Jones from Evanston, Illinois, had discovered a song the Albanians had dedicated to Wilson. It was rare for people in a foreign country to sing the praises of an American president. Therefore professor Jones translated the lyrics and sent them to President Wilson who thanked him for the pleasant surprise.[33]

Konitza placed a wreath on the late President’s sarcophagus located in the lower part of the National Cathedral. The wreath, about three feet in diameter, was formed of pink and white roses and bore the simple inscription “From the Republic of Albania”.[34] Cathedral officials described it as one of the largest and most impressive floral tributes ever brought to the chapel.[35]

At last, Albania was being represented with some dignity in Washington. An Albanian flag was placed at the legation’s door, the telephone number 6288 was registered in the Blue Book of the State Department and the man inside that hotel office was liked by the U. S. hosts. In mid September, Konitza asked his foreign minister, Hysen Vrioni, to be more generous with the budget for the new legation. “It may be a good idea for a poor country to keep its expenses at a minimum and I am happy with what I am paid although sometimes I had to cope with money shortages,”he wrote the foreign minister Hysen Vrioni. “The only thing I am asking, if at all possible, is: I settled in a decent place for legation at a monthly rent of 250 dollars (instead of the estimated 200) for here all the services are included, meaning whenever I have guests, there are servants who can cater for them. This place called The Mayflower is a sort of hotel with a separate section of apartments where a number of senators and diplomats reside.”[36] Vrioni assured the Minister that everything would be taken care of. He promised he would find the money to pay for the expensive rent.

But soon thereafter it became clear that the government was short of money. The funds for the legation routinely arrived late. In November, the Ministry received an ultimatum from Konitza, who complained that he was not being paid. “The logical conclusion is that this legation should be eliminated,” his telegram said.[37] This was his first direct encounter with the Ministry in Tirana. It must have beeen a unique case in which a diplomatic representative asked the Albanian government to close his position. The Ministry tried to calm the situation. Obviously, the funds for the Albanian legation were not a priority for Zogu who was faced with other troubles. On November 20th, a rebellion that shook the regime erupted in the North. Its origin was unclear. It could have been a work of the Yugoslavs, who like the Italians had proposed to Zogu a treaty of friendship and security. The President sounded the alarm and several thousand troops and gendarmes were sent to the North. On November 23rd, Konitza went to the State Department and reported that the uprising was put down and that the actions of the Albanian refugees in Yugoslavia against the Albanian government were funded by Moscow.[38] Konitza was referring to Fan Noli and his followers, who were being labeled as “reds” by Dielli.

After this, the image of the Albanian President abroad needed a boost. In an interview that was printed in many U. S. newspapers, Konitza told the Associated Press: “Albania has one of the most remarkable state executives now in office any where in the world… a man peculiarly fitted to lead his nation towards independence after more than 500 years of Turkish domination. An hereditary bey – a title he has discarded – he is one of the few who has survived the ravages of malaria and other deseases and retained the energy which, in classic times was attributed to Albanians generally.” Konitza went on to describe the meteoric rise in power of Ahmet Zogu, who became interior minister at 26 and prime minister at 28, and his other qualities. “Zogu forced the aristocratic class to pay taxes. Although he works 14 hours a day he takes great pleasure in social functions, is a patron of the arts and recognized as the best dressed man in Albania and a most desirable dancing partner by the young women who know him,” Konitza said in an obvious attempt to lure newspapers that had an appetite for sensational news from exotic lands. He illustrated the energy of his boss with an example from the uprising in the North: “News of a revolution reached Zogu late one night at a large formal dinner. Leaving immediately, he assembled a handful of loyal troops, led them into the mountain stronghold of the rebels, and quelled the disturbance in short order.”[39]

Two American diplomats

In the second half of 1929, after more than four years of diplomatic service in Albania, Charles Hart was appointed by President Herbert Hoover as plenipotentiary minister to Persia. Hart had started his career as a Washington correspondent for several newspapers based in Portland, Spokane and Minneapolis and one could easily spot in him the curiosity and the spirit of an explorer. He had a special link with Albania and played a remarkable role in helping the country in a number of aspects he considered of vital importance, such as education and the fight against malaria. Konitza had a great appreciation for all this.

However, in the summer of 1929, when Hart came to Washington, D.C., for a brief stay, Konitza was away, vacationing on the ocean shore in Swamscott, Massachusetts. Zog’s closest confidant, Abdurahman Krosi, became irritated and called Konitza’s behaviour an affront to the American friend.[40] He told the American Minister on his return to Tirana that if Konitza had a sense of duty, he should have accompanied the Minister during his entire stay in Washington.[41] Hart did not make a big deal of it but later, it turned out that Konitza had been advised by his personal doctor, Robert Oden, to take a vacation as a cure for his hypertension.[42] It is not clear whether Konitza learned of Krosi’s complaint but in October, when Hart returned to the U.S., Konitza invited him to Boston and visit Vatra’s office. He put up a large dinner in The Bellevue hotel and both he and Hart made speeches. Konitza urged Hart not to interrupt his links with Albania. He said: “Your many friends in Albania wish that in the future, you return there every year to spend part of your vacation among the people who know and love you.”[43] Hart said, in Albania he witnessed the “stabilisation of government, and the implementation of a great program of improvements, such as the construction of roads, bridges and power stations and more importantly of a general expansion of the public school system.”[44] “I would not exchange my four and a half years in Albania with any other period of my life,” the American Minister said.

In fact, Hart’s service in Albania had all the elements of an adventure. He had closely followed the strengthening of the new state under King Zog. He had witnessed the arduous efforts of the poverty stricken society to learn from the outside world and rid the blood feuds. He had also witnessed the increase of the Italian influence in Albania. Personally, Hart didn’t appear to have great sympathy for the King, and on one occasion he even reported to Washington that Zog “has done nothing for his own people”.[45] However, he maintained close relations with the King, whose respect for America was indisputable. Those relations were such that in one case, when the Minister was about to travel back home, Zog asked him if he could find him an American wife provided that she was both attractive and rich. As the Associated Press reported later, Minister Hart searched and returned to Albania with a long list. However, the condition that the girls had one million dollars disqualified them all.[46]

In 1929, Presidenti Hoover appointed another journalist to replace Hart as Minister to Albania. This was a prominent Jew named Herman Bernstein. He was born in Russia and had come to the U.S. when he was 17. Bernstein had made quite a career with the interviews that, as a New York Times correspondent in Europe, he had done with some of the world’s best known personalities, such as Pope Benedict XV, Woodrow Wilson, Henry Ford, Leo Tolstoi, Leo Trotzki, Albert Einstein, Hans Delbrück, Henri Bergson, Bernard Show and Auguste Rodin.[47] Bernstein had authored the book Herbert Hoover, the Man who Broght America to the World. His impressive resume also included novels and literary translations from the Russian language.

Bernstein was nominated to serve in Albania in unusual circumstances. In 1920, the sensational newspaper The Dearborn Independent, controlled by Henry Ford, the automobile magnate and the richest man in America, began publishing a series of antisemitic articles. A year later, asked about the articles, Ford said that a prominent Jew had stated to him that the Jews were responsible for the World War and that they controlled the world through the control of gold.[48] Later, when pressed, Ford disclosed that this man was no other than journalist Herman Bernstein. In 1923 Bernstein sued Ford for defamation, demanding that he pay him 200 thousand dollars in damages. Four years latter, the case was settled in Bernstein’s favor.[49] Ford apologised and retracted the writings. The two men remained friends. According to press reports, Bernstein believed that Ford had intervened with President Hoover to make him America’s diplomatic representative to Albania.[50]

At the end of March 1930 a great dinner was put up in New York’s Astor hotel on the eve of Bernstein’s departure to Albania. Konitza, who was among the guests, held a speech. “Bernstein – he said – incoporates in his persona two things that rarely stay together: the dream and the action. He is both a man of letters and of action, both a dreamer and a fighter.”As usual, here too Konitza used his sarcastic style harping on his beloved theme, the image of Albania: “There is something that Bernstein will notice immediately – he said – and that is the big difference between Albania as it is and Albania as it has been described by the journalists. There are two kinds of journalists: the historian journalists, who follow carefully and with conscience the present history as it unfolds before our eyes, and the poet journalists, who get their news not from the outside sources but only from their phantasy. So far, most of the journalists that have dealt with Albania are of the second kind.”[51] Konitza had harsh words especially against those who “invented news about the King of the Albanians”: “Sometimes they describe him as a small and fat man dressed without taste, sometimes they portray him as a merciless person, other times as a scared man that goes out of his way to protect himself and other nonsense. In fact, King Zog is a young man of 35 years, civilized and with a fine taste. He dresses in style and without glitter. He is not only the most handsome but also the ablest of all the living kings today… The value of a person, especially a man of that stature is not measured through phantasy but through a patient and thorough study of the facts.”

Bernstein presented his credentials to Zog on April 29, 1930. Since then, this untiring man never ceased sending detailed reports on Albania to the State Department. The National Archive near Washington, D.C. contains his long letters on the reality of King Zog’s Albania, with which a whole history of that period could be written. Faik Konitza’s brother, Mehmed, was an important source for those reports. Between 1930 and 1933, Mehmed, this fragile man, was one of closest advisors to the King and Bernstein could not expect more confidential and accurate information than what he got from his pro-American friend, whom he described as a patriotic, humanitarian and wise human being.

As a professional journalist and writer, Bernstein was extremely interested in learning the internal workings of the Albanian Kingdom. He wanted to be informed on the sympathies of the cabinet ministers, how corrupt they were and which foreign country they served. On one instance, the diplomatic representative of Yugoslavia in Tirana, Nastasijevic, had implied to him that he saw nothing wrong in the fact that the Interior Minister, Musa Juka, the most powerful man in the cabinet, had been in his pay. Nastasijevic was simply irritated that Mr. Juka was now receiving money from the Italians.[52] Bernstein believed that corruption among Zog’s ministers had become routine. This was reinforced by what Mehmed confessed to him about the ministers. “They take money from both sides, sometimes from three,” Mehmed had told Bernstein on one occasion. “But as a rule they give nothing back to those who pay. In most cases they do what is best for Albania.”[53]

By an interesting coincidence, both Herman Bernstein and his counterpart in Washington, Faik Konitza, were ministers of high learning; they were both prominent writers and historians each in his own merit. But while Konitza did not bother to write reports to his Foreign Ministry, Bernstein could not resist the temptation of describing in minute details to his superiors everything interesting he saw and heard in Albania. He was intrigued by King Zog’s Court, in which conspiracies and dirty little schemes thrived.

The friendship with Mehmed may have helped the American Minister form a positive impression of Albania and Faik Konitza highly appreciated that. In 1932, when Bernstein returned to the U.S. for a short vacation, Konitza went to New York to meet him and invite him to dinner as if he was an old friend.[54] During his stay in the U.S. Bernstein said a lot of good things about Albania. In a romantic portrait of the country and its customs, Bernstein wrote: “In Albania, the Orient and the Occident rub shoulders as in few other lands. The Albanian women are held in high esteem by the men. A woman traveling alone is safe anywhere in Albania. And no man need fear the ancient vengeance of a foe if accompanied by one of his women-folk.”[55] On Zog he said: “He is a tall, intelligent young man of 36 who bears himself with simple but impressive dignity and poise.”[56]

His relations with the King became very close. Zog had asked Bernstein several times to help him find an American bride, just as he had done with Hart before. Zog approached the Minister through his confidant, Abdurahman Krosi. “A refined, energetic and democratic American woman would be a fine example to our people…and if such a match could not be arranged, Zog would rather remain a bachelor,” Krosi told Bernstein. The American Minister declined to help in this delicate matter.[57] In one instance, Zog noticed Bernstein’s mechanical refrigerator in the Minister’s residence and asked him to order one for himself. In no time, the refrigerator arrived, the third such machine ever imported in Albania after the first two in the American legation.[58] In 1933, in a case that can be seen as rare for a U.S. chief of diplomatic mission, Berstein undertook to write a detailed story of King Zog’s life on the basis of many questions he had presented to him through Mehmed. The result was a long biography of the Albanian monarch narrated in the third person by the American Minister.[59]

When President Hoover lost his reelection bid in 1932, Konitza wrote to Bernstein: “The result of the elections might, I fear, curtail your diplomatic mission to Albania; and I know that Albania would thereby lose a good and sincere friend. Howeever I hope that your connection with the country will never cease.”[60] Bernstein left Tirana in September 1933. A few months later, King Zog honored him with the Grand Cross of the Order of Skanderbeg, the highest award conferred to a foreigner by Albania. Konitza brought the medal and the diploma to a ceremony organized on March 23, 1934 at the New York’s Ritz Carlton. Bernstein could not hold back the emotions. Turning to Konitza and others he said: “America and the Americans are extremely popular in your country. They remember how President Wilson helped Albania at the Peace Conference to regain her independence, and they also remember what the Albanians in the United States have done to save and make secure your independence. Albania is one of the few countries in Europe that owe the United States only moral obligations and debts. That has added to America’s popularity in Albania.”[61]

About a year later, when Bernstein published his book entitled Can We Abolish War? with opinions from dozens of world celebrities on war and peace issues, Konitza was among the first to congratulate his friend.[62] This was his last letter to him, because shortly afterward, on August 31, 1935 Bernstein died of a heart attack. Konitza learned the sad news a few weeks later from the press when he returned to Washington from his vacation in Swamscott.

[1] Frank Kellogg to President Coolidge, April 5, 1926, Calvin Coolidge Papers 1915-1932, Library of Congress, Manuscript Division, Microform 178/3456.

[2] Faik Konitza, “Lamtumir”, Dielli, July 3, 1926.

[3] C. C. Hart to Secretary of State, December 10, 1925, National Archives at College Park, Maryland [NACP] 701.7511/12.

[4] Athanas T. Body (Boston), Letter to the Department of State, June 27, 1926, NACP 701.7511/16.

[5] Faik Konitza, “Lamtumir”, Dielli, July 3, 1926.

[6] Division of Near Eastern Affairs, “Memorandum”, April 1, 1926, NACP 701.7511/13.

[7] Telegram of Faik Konitza to the Foreign Ministry, July 13, 1926. Archive of Foreign Ministry of Albania, Tirana, 1926.

[8] “Mbi kompetencat: Korrik, Gusht e Shtator”, Foreign Ministry letter to Konitza, July 11, 1926. Foreign Ministry Archive.

[9] Diana L. Bailey, The Mayflower, Washington’s Second Best Address (Virginia Beach: The Donning Company Publishers, 2001).

[10] The Mayflower Log, July, August, September 1926 issues, Martin Luther King Library, Washington, DC.

[11] Haris Silajxhic, Shqipëria dhe SHBA në arkivat e Washingtonit (Tiranë: Dituria, 1999), translated by Xh. Fejza, p. 127.

[12] W. S. Mann: “Diplomats Many Lands Crowding Nat’l Capital”, Fayetteville Democrat (Arkansas), May 12, 1920.

[13] Phyllis Cole Braunlich, Stone Pillows, (Xlibris Corporation, 2003), p. 221.

[14] Ibid.

[15] “Ambassador to Italy (Child) to Secretary of State”, April 3, 1922. Foreign Relations of the United States [FRUS], (Washington: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1922), V. I, pp. 594-596.

[16] “Albania Desires U.S. Recognition”, Reno Evening Gazette, (By Associated Press Mail). June 17, 1922.

[17] “Commissioner in Albania (Blake) to Secretary of State”, June 28, 1922. FRUS V. I, pp. 602-603.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Jup Kastrati, Faik Konitza (Monografi) (New York: Gjonlekaj Publishing Company, 1995), p. 171.

[20] H. Silajxhiç, Shqipëria dhe SHBA në arkivat e Washingtonit, p. 127.

[21] Today Georgetown University. Chekrezi returned to Albania in 1925.

[22] “Royal Mate Sought By Zog”, The San Antonio Light, (Universal Service) December 6, 1931, p. 11.

[23] Uran Butka, Gjeniu i Kombit (Tiranë: Drier, 2000), p. 221.

[24] F. Konitza to Secretary of State, undated letter, received on September 19, 1922, NACP 701.7511/3.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ulysses Grant-Smith to Secretary of State, Tirana, January 6, 1923, NACP 701.7511/6.

[27] “Memorandum of Conversation with the Consul of Albania, Mr. Sula”, July 16, 1924, NACP 701.7511/11.

[28] “Conversation with Mr. Tashko, Acting Consul of Albania in New York City”, January 25, 1925, NACP 875.01/262.

[29] C. C. Hart to Secretary of State, November 23, 1926, NACP 875.00/215.

[30] Owen Pearson, Albania and King Zog, (London: Centre for Albanian Studies, I B Tauris & Co Ltd, 2004), p. 285.

[31] F. Konitza, Letter to Secretary F. Kellogg, October 1, 1926, NACP 701.7511/22. Also see Dielli October 15, 1926: “Z. Konitza çmon përkrahjen amerikane për indipendencën e Shqipërisë pas Luftës së Madhe”.

[32] The tradition continues today. In the 2010 electoral lists in Tirana, there were 218 voters named Vilson and 47 Yllson.

[33] “An Ode to Wilson and America”, 02.28.1921, NACP Microfilm Publications, M1211, Roll 15. Also see Wilson’s letter to Prof. Elmer E. Jones.

[34] Wilson’s tomb was later placed in another part of the Cathedral.

[35] “Albanian Minister At Tomb of Wilson”, The Washington Post, October 26, 1926, p. 24.

[36] F. Konitza, Letter to Minister Vrioni, September 17, 1926. Foreign Ministry Archive.

[37] F. Konitza, Telegram to the Foreign Ministry, November 8, 1926. Foreign Ministry Archive.

[38] Maynard B. Barnes. “Department of State. Conversation with Albanian Minister, Mr. Konitza”, November 24, 1926. NACP 875.00/214.

[39] “Strenous and youthful, Zogu leads Albania towards freedom”, The Havre Daily News-Promoter, March 14, 1927.

[40] After proclaiming himself King in the fall of 1928, Zogu changed his last name to Zog.

[41] C. C. Hart to Secretary of State, August 1, 1929, NACP 875.00/273.

[42] “Mr. Faik Konitza”, Dielli, June 7, 1929.

[43] “Ministri i Amerikës Charles C. Hart vizitor i Vatrës”, Dielli, October 25, 1929.

[44] “Një intervistë me ekselencën e tij Ministrin Charles C. Hart”, Dielli, November 22, 1929.

[45] C. C. Hart to Secretary of State, November 23, 1926, NACP 875.00/214.

[46] Associated Press, “King Zog Wants American Spouse”, The Kingsport Times (Tennessee), January 21, 1935, pp. 1, 6. Hart denied the newspaper reports.

[47] H. Bernstein, Celebrities of Our Time, (New York: Joseph Lawren Publisher, 1924).

[48] Neil Baldwin, Henry Ford and the Jews, (New York: Public Affairs, 2001), p. 164.

[49] Ibid, p. 241.

[50] UP, “Man Who Sued Ford Appointed Minister”, The Charleston Daily Mail, February 9, 1930.

[51] “Një darkë nderi për Ministrin e ri t’Amerikës”, Dielli, April 4, 1930.

[52] H. Bernstein to Secretary of State, March 12, 1931. NACP, M1211, Roll 8.

[53] Ibid.

[54] “Një darkë për nder të Ministrit t’Amerikës në Shqipëri”, Dielli, May 20, 1932.

[55] Harold T. Horan: “The Land of the Eagle People”, The Washington Post, March 6, 1932. p. 7

[56] Ibid.

[57] H. Bernstein to Secretary of State, December 5, 1930, NACP 875.001-ZOG/35.

[58] “Introduced Mechanical Refrigeration In Albania”, Hamilton Evening Journal, May 9, 1932.

[59] The origjinal of the biography is in The Papers of Herman Bernstein, Box 31. Also see R. Elsie, “King Zog Tells His Story”, www.albanianhistory.net.

[60] F. Konitza to H. Bernstein, November 15, 1932, The Papers of Herman Bernstein, Folder 758.

[61] Speech by H. Bernstein, March 23, 1934. Ibid, Folder 751.

[62] F. Konitza to H. Bernstein, The Papers of Herman Bernstein, Folder 758.