By Sokol Lleshi

Introduction

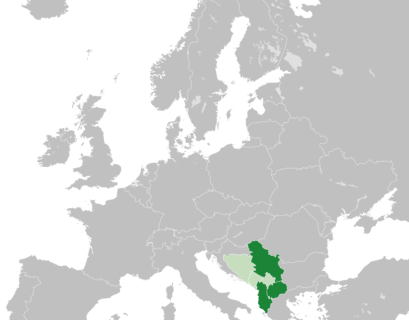

The fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 and the relative ineffectiveness of the Gorbachev’s reforms (Lewin, 2005; Petrov 2008) in order to restore the revolutionary ethos of the pre-Stalinist Bolshevik ruling practices and accelerate the process of reconstructing the political and economic spheres towards further inclusion and accountability between state and society has had diverse consequences in Eastern Europe. In fact, the assumed universality of the terms such as perestroika and glasnost (Petrov, 2008, p. 187) was not reflected equally on the verge of political and economic transformations across East Central Europe. In countries such as Poland, Hungary or Czechoslovakia there existed, to different degrees, social mobilizations against the regime and a resurgence of civil society that was gaining its autonomy from the party state. On the other hand, the social category of dissidents in the above mentioned countries produced genuine political thought and concepts (Falk, 2003) that were rooted in their cultural tradition and actual political dynamics of intellectual dissent since the early 1960s until 1989 in the region. Whereas in communist countries where such a tradition of dissent was lacking or quite sparse one witnesses a circulation and dissemination of the concepts and approaches designed by Gorbachev and the intra-elite group that supported the transformation of the status-quo in the Soviet Union. I am referring here to countries that could be placed in semi-periphery or periphery of the global influence of the Soviet Union within Eastern Europe such as Bulgaria, Albania, or Romania. In this respect, the focus of this paper is to address the extent to which relevant factions of the ruling elite of the state socialist regime in the periphery of the East Central Europe, such as Albania, borrowed and used the ideological blueprint of perestroika in order to solve the legitimation crisis of the late 1980s.

The objective of the paper is to reconsider the common sense understanding of the communist regime in Albania, which is generally characterized as remaining Stalinist and totalitarian since its inception until the end. That is not to condone the crimes and the repressive features of the dictatorship neither to praise the assumed modernizing or so-called emancipatory goal of the communist regime itself. Yet, the empirical evidence indicates that in the late 1980s the Albanian state socialist regime considers replacing the dogmatic Marxist-Leninist ideological legitimation and the nationalist legitimation (see Tismăneanu, 2003) of Stalinist type with a more expertise-based and universalistic ideology that would temper the schematic and doctrinaire features of the Marxist-Leninist ideology. Despite the proclaimed continuity with the previous Stalinist ruling practices of the regime, and the ferocious public criticism of current revisionism (an allusion to Gorbachev) and bourgeois capitalist states, a close circle of party ideologues and key representatives of the nomenklatura led by Ramiz Alia started using a different ideological frame and terminology regarding the ‘construction of socialism’ in Albania. By studying and exploring the official public discourse of these representatives and other influential members of the regime one notices a difference between two prevailing factions within the Albanian Labor Party. One faction represented by conservative and loyalists to the Stalinist legacy of the communist regime emphasizes continuity and status-quo, being not in favor of reforms. The other faction represented primarily by the General Secretary of the PLA and his inner circle does not disavow socialism completely yet aims to restructure the command economy by providing more autonomy to the managers and to induce the professional class to deliberate on innovative or creative ways of reforming socialism. The more reformist faction had the upper hand despite the discursive ambiguity and hesitations regarding the scope of the reforms. Challenges to regime transition were not lacking either. One could refer to the societal mobilizations of dogmatic regime supporters from local communities in defense of the Stalinist legacy of the dictatorship and the attempted military uprising by cadets of the Army School in February 1991. The protracted dynamics of regime change in Albania, this paper claims, could be better explained by the conceptual framework devised by McFaul (2001) to explain regime dynamics in the Soviet Union. This framework could actually provide a plausible explanation to absence of democratic consolidation and frequency of regime cycles (Hale, 2005) in Albania.

The first part of the paper delineates the historical context of the political dynamics of the Soviet Union aiming to reform existing socialism and how this process, which was initially conceptually distinct from liberalization led to regime transition in which the validity of the perestroika reforms is disputed. The second part of the paper focuses on the attempts by the Albanian state socialist ruling elites to provide a different grounding of the state socialist regime, without relinquishing the power monopoly of the PLA, by borrowing from the ideological framework of perestroika and glasnost. The conclusion tries to address the broader issues and implications of the fall of the Soviet Union on political and economic transformations in post-communist Albania.

Soviet Union: From Stalinist legacy and command economy to the reconstruction of socialism

High Stalinism

It is already a shared understanding, if not a trivial common-sense, that the fall of the Soviet Union was not predicted neither predictable by the scholarly community. Moreover, the actual economic and societal indicators did not reveal a crisis (Rutland, 1994). As Moshe Lewin (2005) argues, a linear and fixed conceptualization of the Soviet Union, or any other state socialist regime for that matter, would be misleading and not empirically grounded. “The tendency to perpetuate Stalinism by backdating it to 1917 and extending it to the end of the Soviet Union, pertains to those ‘uses and abuses’ of history which there are many examples” (Lewin, 2005, p. 4). Hence, in order to understand internal changes or transformations within the Soviet Union a certain periodization of the regime is warranted. The period coined as High Stalinism was characterized by industrialization that entailed “the replacement of small, supposedly inefficient producers by larger and therefore mightier ones” (Kotkin, 1995, p. 20). Five-year plans became a central feature of the command economy, which persisted despite the radical period of market reforms initiated by Gorbachev. Collectivization, in fact a forced one, became another important staple of Stalinism. Paul R. Gregory (2004) summarizes quite well the political economy and political institutions of Stalinism: “The Soviet Union would thereafter be directed by a national plan to create an industrialized economy in the shortest possible time, characterized by collectivized agriculture, state ownership, and a dictatorship by the Communist Party, which would speak with one voice and would allow no internal opposition” (2004, p. 24). Scholars such as Stephen Kotkin (1995), observing similarities between the West and Soviet Russia in terms of what Kotkin terms as “progressive modernity” consider High Stalinism as a period of ushering “a new civilization called socialism” (1995, p. 14). What remains important to the focus of this paper is the interaction between state bureaucracy and party apparatus as well as the composition of the social forces under Stalinism. The state bureaucracy was not fully under the control of the party. Parallel structures were created with the same function in the party apparatus to mimic the functions of the state bureaucracy (McCauley, 2007, p. 170). The Party nomenklatura (McCauley, 2007) was reinstated as the mechanism to influence the appointments of key state and party positions. This particular overlap between party apparatus and state bureaucracy led to what was called during Gorbachev’s rule as the bureaucratization of the party (Lewin, 2005, p. 40). The party, according to Lewin (2005, p. 37) was transformed by Stalin in an instrument to control the state. The unintended consequence of the establishment of the parallel structures and the nomenklatura mechanism was the bureaucratization of the party, which Gorbachev and his inner circle intended to change.

The configuration of the social forces during the Stalinist phase of the Soviet Union persisted even in later stages of the regime. Workers and peasants were distinguished from the category of specialists, managers, creative intelligentsia and party bureaucracy. What actually changed during perestroika and glasnost was the balance of forces within the ruling elite. Albeit the fact that the social category of the specialists, with technical education mostly, were important for the industrialization (McCauley, 2007, p. 166; Lewin, 2005, p. 55) and those managers of enterprises being members of the technical intelligentsia (McCauley, 2007, p. 167) were influential to some extent, the prevailing capital was the political capital represented by the party bureaucracy. The balance of forces changes during the time of perestroika, in which the technocratic intelligentsia and the creative intelligentsia (Lewin, 1989) is granted more autonomy and becomes part of the ruling elite of the late socialism during Gorbachev.

The Ambiguity and Irony of the Perestroika

What initially started as reconstruction and reformation of existing socialism turned out to be ultimately a first stage of the regime transition to market economy and a post-authoritarian regime after the fall of the Soviet Union. The disintegration of the Soviet Union as a federation was predicated on societal and national mobilization against the existing institutional structures of the Soviet Union. The Baltic republics, and particularly in Lithuania with the establishment of the Sąjūdis movement in 1988, claimed pro-independence goals (McCauley, 2007, p. 413). Purposeful societal mobilization at the level of the republics was due to the recognition by the Soviet elite that the reconstruction of existing socialism entailed the inclusion of the masses and not simply the party bureaucracy in what was termed as reformism or democratization. On the other hand, the balance of power (McFaul, 2001) between reformist and the conservative faction within the Russian republic of the Soviet Union that had its pinnacle with the August coup attempt in 1991 led to the establishment of an independent Russia. Henceforth, the intention to preserve the Soviet Union federation was challenged. As Petrov emphasizes: “Perestroika and other key concepts were erased from the political map along with the Soviet collapse. The concepts had been used to comprise many increasingly diverging and contradictory notion” (2008, p. 186). In fact, ultimately the reformist reconstruction became prone to de-ideologization because of the “disappearance of the last remnants of the ideology’s specific identity” (Petrov, 2008, p. 187). There was more and more reference to market economy reforms and capitalist undertones. However, it is important to disentangle the process of reforming existing state socialism in Soviet Union and the repercussions that this process had for the periphery of the countries in communist Eastern Europe as well as for the outcome of regime transition.

Supported by internal members of the Politburo, Gorbachev obtained the position of the General Secretary of the CPSU in 1985. He defined the need for reforms as: “We are living through a very difficult period of transition. Our economy needs rejuvenation as does our democracy, and foreign policy…we must move ahead, identify defects, and remove them” (McCauley, 2007, p. 398). The most obvious culprit for the stalling of reforms and the status quo according to Gorbachev was the party bureaucracy. “The drift of the letter was that the Party administrative stratum, the middle level officials, was holding up the transformation of the country” (McCauley, 2007, p. 402). The initial aim of the restructuring was the economy. Later this goal was accompanied with that of glasnost, that involved open deliberations on policy matters, that should not remain an exclusive domain of the party bureaucracy. We experience the same policy goals in the late 1980s in the state socialist regime of Albania, although the ideological buzzwords remained that of ‘building socialism’ and ‘revolutionary militantism’. Despite this contradiction, there is an actual resemblance of the attempted reforms of the Albanian ruling elite and the reforms of Gorbachev.

Moshe Lewin contends that under Stalin the party was an instrument of the dictator. After the thaw, Khrushchev “aimed to reinvigorate the party and restore the status and power of its apparatus by strengthening its ideological role” (2005, p. 218). Iakovlev, a key representative of the inner circle of Gorbachev that actually embraced social-democracy earlier than Gorbachev, identified the existence of parallel structures between the party and state administration as a pressing issue: “…a struggle of utmost vigor must be conducted against bureaucratization inside the party itself. According to him the phenomenon could be explained by the fact that so many party members worked in the state administration and there acquired pernicious habits with which they were contaminating the party” (Lewin, 2005, p. 40). To remedy this condition Gorbachev started to disinvest the party bureaucracy from controlling the economy and giving the managers and professional class more autonomy. On the other hand, allowing the masses and citizens to have a say in party structures or to establish informal association and pitting them against the intelligentsia was another strategy that was used. “Another group which came in for sharp criticism was the intelligentsia. A campaign began in the second half of 1987 and continued until early 1989. This was a period when peasants and workers were being favored over the intelligentsia” (McCauley, 2007, p. 415). However, what distinguishes the outcomes of the perestroika and glasnost in the case of the Soviet Union, from the one in state socialist Albania, besides the fact that the former was a federative structure and the latter a unitary one, before regime transition took place, was the establishment of informal associations against the regime and an initial reckoning with the authoritarian past. “In September 1987, the Politburo set up a commission on the rehabilitation of the victims of repression” (2007, p. 407). At the same time informal associations in civil society and civic demonstrations took place in Moscow in 1987 (2007, p. 408). The Albanian state socialist regime did not initiate any measure, albeit limited, concerning the authoritarian past while aiming to sustain the regime with reformist instruments. On the other hand, with the exception of a demonstration in January 1990 in Shkodër, there was no demonstration in the capital city throughout the late 1980s.

As for economic reforms, which initially constituted the backbone of the perestroika, by 1988 the ruling elite aimed for market reforms, which actually diluted, as Petrov (2008) argues, the ideological dimension of reinvigorating existing socialism. The law on enterprises: “This law permitted the election of managers and the setting up of workers’ collectives. Full self-financing and self-accounting were envisaged” (McCauley, 2007, p. 405). Another step in the process was the election to the local Soviets and the election to the Congress of People’s Deputies. You could run as an independent candidate not backed by the Party. Informal associations, that became opposition political parties, such as the one headed by Sakharov and Afanasov, created their own caucus in this institution. In fact, what transpired is that “Elections to the CPD permitted the formation of movements, national fronts, single issue groups, and an array of social democratic and religious formations”. (2007, p. 416). Being against the regime increased the chances of winning a contest in this election (2007, p. 416).

It is interesting to note the conceptual transformations and contradictions of the reform initiated by Gorbachev. Petrov (2008) argues that the conceptual foundation of perestroika could be traced back to what he calls the “Soviet ideology of productivity” (2008, p. 182). This feature is also compared to forced industrialization or other innovative and radical transformations in earlier periods of the Soviet regime. The reconstruction of existing socialism in the Soviet Union, albeit the intention to reinvigorate internal deliberations within the Party, could not be perceived as a restoration of past ruling practices before Stalin. In fact, the whole reformist blueprint is fraught with contradictions. The intention to “revise dogmas” (Petrov, 2008, p. 184) that Gorbachev had as a consequence of his political socialization in the 1960s, had led Gorbachev and his allies to identify the “irrational elements in socialism” (2008, p. 183). Yet what happened is that socialism was less and less evoked and the reform actually became anti-Soviet because of not justifying the imperfections of reality for the sake of a distant future (2008, p. 184). It is at this juncture that the party was factionalized into two main groups, the reformers headed by Gorbachev and those that opposed the reform (McCauley, 2007, p. 414).

The equal balance of power between the main factions within the CPSU became, as McFaul (2001) argues, one of the factors that led to the polarization in the early stage of regime transition and inhibited the formation of stable and consensual institutional choice. The process of regime transition after the disintegration of the Soviet Union is categorized as protracted and confrontational (2001, p. 21). A key concept that McFaul uses to explain the cause of the confrontational and absence of a stable institutional choice is the concept of “contested agenda of change” (2001, p. 12). This important concept is defined as follows: “The extent to which plans for reform become contested agendas is the function of the degree of consensus among important political actors and the balance of power among these actors” (McFaul, 2001, p. 12). The attempted military coup in August 1991 and the lack of consensus on the future of the Soviet Union Federation that pitted Yeltsin against Gorbachev indicated an equal balance of power between contending forces during regime transition. As the agenda for reform widened so did the lack of consensus on institutional choice (McFaul, 2001, p. 20). This framework is used to explain the protracted transition and absence of stable institutional choice in the regime change in Albania from 1990-1992. The next part of the paper will discuss the political dynamics of the state socialist regime in Albania in the late 1980s. At this period the ruling elite replaces the regime legitimation based on nationalist-Stalinism with expertise-based legitimation by incorporating as part of the ruling elite the technocratic and creative intelligentsia. Moshe Lewin (1989, pp. 98-99) argues that in the Soviet Union during the perestroika, the Soviet regime put together a new ideology which he describes as: “…a sociopolitical philosophy, an ideology, is coalescing in intellectual, notably scholarly, circles. And the new program is finding support among the political leadership. Is this the renewal of a Soviet version of humanism, is it ‘a liberalism’ Soviet style?”

Ersatz Reconstruction of Socialism in the Late 1980s in Albania

Stages of State Socialist Regime Development

When contrasting the period of the late 1950s to the late 1980s with the time from the mid- 1980s to 1990, one could obtain a better understanding on the transformation of the state socialist regime in Albania as well as the new role of the socialist intelligentsia in relation to the regime. This study bases its arguments partly on Ken Jowitt’s theory (1992) of the stages of Leninist regimes. The Albanian state socialist regime hindered the establishment of a technocratic intelligentsia that could have been influential in the construction of market socialism. However, a process of “opening up [the party bureaucracy] ranks to the intelligentsia” (Szelényi & Martin, 1988, p. 665) took place the late 1980s. The Marxist-Leninist ideological legitimation and the nationalist ideological legitimation, producing a version of national-Stalinism, was in crisis in the mid -1980s. At this critical juncture, the reformist faction of the ruling elite initiates an ersatz reconstruction of socialism as part of a process that could be termed an intra-regime reformist cycle. The ascendency of the cultural intelligentsia, and partly of the technocratic intelligentsia, in the Albanian state socialist regime during the late 1980s reduces the power of the party bureaucracy. The unintended consequences of this process has been that representative members of the cultural intelligentsia ascended to power in the post-socialist regime.

Initially with the ascent to power of the communists after the Second World War, the goals of the socialist dictatorship were to uproot the interwar social formation by weakening and persecuting the representatives of the national bourgeoisie, the merchants, public intellectuals and collectivize the agrarian economy. The coercive mode of legitimation was rather dominant during this period. At this stage, the regime had not established yet a national higher educational system. During the consolidation stage, which could be defined as the period between the 1960s and 1979, the regime attempted certain unsuccessful or intermittent liberalizing reforms. The linkages between the socialist intelligentsia and the state socialist regime were based on “ideological-political orientation” (Jowitt, 1992, p. 74). The socialist intelligentsia followed the party line and its role was to enhance Party propaganda and the ideological education of society. At this stage, political capital was the prevailing capital in the field of power of the state socialist social formation. No clear distinction was made between experts with a “formal role prescription” (Jowitt, 1992, p. 64) and the “politically relevant behavior” (1992, p. 64) of the party cadres.

The weakened role of Marxist-Leninist ideology in the 1980s, and the discontinuity of dependency on a socialist hegemonic power such as the Soviet Union or China, forced the state socialist regime open its ranks in the administrative apparatus and economic sector to non-party members of the socialist intelligentsia. The party bureaucracy was being replaced by the “more professional, skilled and articulate strata (Jowitt, 1992, p. 95). This professional stratum was tasked to respond to the legitimation crisis of the regime and formulated policies in particular to social problems that the regime faced. These changes in the ruling practices constituted an attempt to continue building socialism with other means. It is at this juncture that the regime aimed to “enhance its legitimacy without sacrificing the charismatic exclusiveness of its apparatchik component” (Jowitt, 1992, p. 93). That means that the ruling elite did not renounce the PLA’s monopoly on power. The notion of the co-existence of various principles of legitimation (Rigby, 1982, p. 15) indicates that the symbolic-ideological legitimation (Verdery, 1991) of the Albanian socialist regime was based on national ideology as well as Marxist-Leninist ideology. As stated earlier, the legitimation based on national ideology was less efficient in the mid-1980s, or at least functioned only as a smokescreen. A similar process to the one that took place in the late 1980s in the Soviet Union (see Lewin, 1989), in which the social scientists became instrumental in proposing solutions to the problems faced by the CPSU, took place in the late 1980s in Albania.

Reformist Cycle and Ideological Shift

The Ninth Party Congress of the Party of Labor of Albania (hereafter PLA), held in November 1986, constituted a turning point in the ideological discourse of the leading heights of the Party-state and in the process of reconfiguring the field of power. Ramiz Alia became the first secretary of the PLA after the death of Enver Hoxha in 1985. As Vickers summarizes (2001, p. 210) Nexhmije Hoxha became in 1986 “the chair of the Democratic Front, a mass organization of the PLA in charge of organizing elections and maintaining internal security”. However, as Vickers claims she had little role to play in the reformist cycle (2001, p. 210). The regime’s new leadership loosened the ideological restrictions and limited the use of coercion. Although the regime publicly manifested its ideological objection to “revisionist” policies in the Soviet Union and to “the restoration of the bourgeoisie” in East Central Europe, in facing the uncertain prospective trajectory of the state socialist regime and the existing immobility of the centralized economy, with the waning of its legitimacy among the working classes and young generation (Biberaj, 1998, p. 30), it initiated a reform cycle. The ideological discourse delineated in the political speeches of Ramiz Alia and other leading members of the Party that were part of Alia’s inner circle and supported the reformist cycle, emphasized a recognition of Albania’s changing external and internal conditions. Behind the veneer of ideological correctness and rhetorical exhortations to base “scientific work on revolutionary theory and the on the correct line of the Party” (Alia, 1986, p. 21), the regime recognized and promoted specialization and the expertise of cultural producers. Economists, physicists, mathematicians, and social scientists were asked to provide recommendations and solutions to the pressing problems facing the regime. In consequence, the sharp distinction between the Party bureaucracy and the “unreformed” society was overcome.

During this stage, more and more members of the cultural intelligentsia were recruited to the state bureaucracy and non-party positions. In 1990, before regime change, in a speech on the democratization of social life, Ramiz Alia informed the members of the Central Committee that “in the apparatus of the central departments and institutions, the communists make up only 33 percent of the total number of employees and functionaries, while 67 percent of them are not party members (1990, p. 4). This process, which had evolved over time, happened prior to regime change in 1991. The official discourse during the late 1980s specified the increasing role of cultural capital and the authority of the cultural producers. The existing practice of ideological work was considered by Party ideologues such as Foto Çami to be inefficient and burdened with empty slogans and cliches (1986, p. 36). What was required was “more knowledge, more facts, and arguments” (1986, p. 36). The lofty ideological battles were replaced by concrete social issues (Alia, 1986, p. 12). The state socialist regime accepted the necessity of recognizing the changing role and importance of cultural producers, as part of the socialist intelligentsia. “Currently, society needs people who are quite able professionally and passionate about their expertise, as well as competent in their field” (Alia, 1986, p. 27).

The public speeches of the leading representatives of the Albanian state socialist regime reveal a rift between the conservative faction of the PLA and the reformist faction of the Party headed by Ramiz Alia. It should be mentioned that the representatives of the reformist faction, or that faction that initiated the reformist cycle in the late 1980s did not explicitly refer to the terminology of perestroika or glasnost nor did they present a clear and coherent reformist platform. Yet, in practice, at the center of their ideological shift has been reducing the effect of the party bureaucracy and relying more on the cultural intelligentsia. The agenda of change involved not the relinquishing of the monopoly of power of the PLA but continuing to build socialism through different means. Key terms that are found in the public speeches and official documents of this faction include democratization of the life of the party, expertise, separation of the party bureaucracy from the economic field.

The attack on socialist intelligentsia with the intention to reinvigorate what is usually termed as “our communist militantism” (Çami, 1986, p. 33) was seen as a temporary strategy to increase the participation of the cultural intelligentsia in the “ideological front of the Party”. (1986, p. 33). “All those that are militating in the ideological front, should always be attached to the life of the masses and to the duties demanded by the Party, and not to be bystanders and onlookers, but active participants in the battles for the socialist construction of the country, social activists engaged and interested on everything happens in the life of the country” (1986, p. 33). Discussing what are the sources of the ideological shift and of the reformist cycle, the Party ideologue that was closer to the reformist faction of the PLA hints that progress or humanism widely conceived are the basis of the change rather than “copying or mechanical application of the experience of others” (1986, p. 34). “[Reforms] do not mean to remain isolated. Instead, the Party and its worldview requires that our people master and obtain every single thing that is good, useful and progressive created by humanity and to apply that in the service of the people, motherland, and socialism” (1986, p. 34). The actual practice through which the absorption of new ideas and progressive ideas need to take place, according to Foto Çami, under conditions of “open deliberation where everything follows the sound logic of scientific argumentation, free from any arbitrary qualification of thought that is usually manifested through the false imposition of authority of the status and rank” (1986, p. 34). It seems like the Albanian version of glasnost based on Habermasian communicative rationalism.

There is also a recognition of partial failure of economic policies. “There have been years now since the Party has observed a certain lagging behind of the economic thought, which despite all the efforts taken, has not been overcome yet. This backwardness is manifested particularly in the studies that have to do with the improvement of the relations in the production sphere” (1986, p. 35). Later during the reformist cycle, the First Secretary of the PLA made a strong statement: “The Party cannot interfere in the economy” (Alia, 1990, p. 17). After initially proclaiming the Marxist-Leninist doctrine as theoretical basis upon which socialism is built (Alia, 1986, p. 9), the General Secretary late in the text admonishes the laggards and the bureaucrats “who stick to one way of doing things and do not want to think or move their body” (1986, p. 11). He argues that what the Party demands is that “in every department, party committee, state bureaucracy, economic sector, at scientific institutions and at university, the creative initiative and thought of the masses needs to be reinvigorated and that people need to express their ideas and thought openly without constrain making suggestions and proposals for the betterment of the processes in the benefit of building socialism” (1986, p.11). Ramiz Alia does not renounce socialism and its ideology, yet he uses the practices of glasnost borrowed from Gorbachev’s universalized frame of perestroika. Further on, in the official report to the Ninth Congress of the PLA, the General Secretary seems to emphasize at the level of political rhetoric and discourse the political goal for “regular systematic and open information on everything that happens in the life of the country, which increases the creative initiative and active participation of the masses in the government of the country and increases the democracy of our socialism” (p. 20).

The conservative faction of the PLA did not seem to welcome the reformist cycle of the Secretary General of the Party. This faction emphasized continuity and the assumed uniqueness of building socialism in Albania. “The historical duties that we are facing today as a society require that even the scientific activity should be permeated by militant revolutionary spirit” (Hoxha, 1986, p. 39). These official documents are characterized by praise for the ‘authenticity’ of socialism in Albania: “There is no secret or Albanian “enigma”. But there is an experience which we may consider unique” (Hoxha, 1986, p. 40). Direct attack against the Soviet Union’s reforms are made by this particular representatives of the status quo in the Party: “It is precisely this path that our Party has taken, which is loyal to the Marxist-Leninist ideology that has actually stabilized the foundations of socialism in Albania. Meanwhile, the revisionists in the Soviet Union and in other countries gave in to pressure of the bourgeoisie and imperialism and opened the way to the restoration of capitalism” (1986, p. 41). The more liberal faction of the PLA ruling elite had the upper hand in the process of controlling the process of liberalization prior to regime change. Despite the assumed loyalty expressed to the Stalinist legacy of the state socialist regime since the post-war period, influential members of the ruling elite initiated certain changes, however insufficient or timid (Vickers, 2001, p. 213), that built upon the ideological and normative borrowings from the template of perestroika and glasnost in the Soviet Union. This process was done quite indirectly and without any explicit support or reference to the reformism of Gorbachev. Referring to humanity, progress, democratization of party life and the need for professional expertise constituted the linchpin of the reformist cycle strategy of the General Secretary of the PLA and inner circle within the Party.

It is ironic, and probably a moment of reflection, that the General Secretary of the PLA in the late 1980s does not refer any longer to the imperfect present that needs to be accepted as a consequence of a better future, to borrow the terminology used by Lewin when referring to Gorbachev. Some of the statements made in the official texts by Ramiz Alia indicate an assessment of what socialism was in Albania and what its after-effects were: “If we consider our progress in the economy as incomparable with the past, the transformation of political and ideological persuasions of the people, changes in mentality and individual psychology, as well as the way of life and social relations are unprecedented” (1986, p. 7). It seems more like a reflection of what has transpired rather than what is about to happen in the future regarding the building of socialism in Albania.

Conclusion

The theoretical goal of this paper was to reconsider the assumed one-dimensional character of the state socialist regime in Albania as totalitarian or Stalinist from the beginning after the end of the World War II till its fall in 1991. The empirical evidence based on the public discourse of the key representatives of the regime shows that the national ideology and Marxist Leninist doctrine were no longer useful for the legitimation of the state socialist regime. Albeit the fact that the Party did not renounce the monopoly of power and embrace political pluralism, certain strategies were followed to include non-party members and representatives of the cultural intelligentsia in the decision making of the regime. As a consequence, there was an opening towards the social scientists in the late 1980s and towards more practical changes in the policy that had to do with tackling social problems and the economy.

On the other hand, the goal of the paper has been to show the similarities and the difference between the reforms initiated by Gorbachev from 1985-1990 based on the key concepts of perestroika and glasnost and the reformist cycle undertaken by the liberal faction of the PLA headed by Ramiz Alia. This is not to exonerate the state socialist regime representatives neither to glorify them. The empirical evidence and in particular the political discourse shows that ideological and normative borrowings, albeit implicitly, have taken place. The outcome of the reformist cycle was most probably the continuous influence of the state socialist regime representatives in the process of regime transition. Contrary to other post-communist transformations where the representatives of ancien regime surrendered to the mobilizational pressure of civil society and democratic opposition, in the case of Albania the regime transition pitted two equally strong groups. On the one hand, there was the reformist group of the state socialist regime that had the upper hand compared to the conservative faction, and on the other hand there were the representatives of the cultural intelligentsia that had migrated to the civil society and established the Democratic Party of Albania, as the first opposition party against the regime. The process of democratic transition was rather protracted and non-conclusive in terms of institutional choice and consensus-based pacts.

The initial agenda of change that focused on economic reform towards market capitalism and the building of new political institutions of the post-communist Albanian society converged towards some degree of mutual consensus between the Democratic Party and the ex-communists represented by the Socialist Party of Albania (Biberaj, 1998). However, the co-existence of the two equally powerful political blocs did not last long as a consequence of other items that were included in the agenda of change. A key feature of the contested agenda of change, to borrow the term coined by McFaul, had to do with transitional justice policies during and immediately after regime transition. There were attempts to draw a thick line on the past and to achieve some modicum of reconciliation between the parties and social groups. Yet, there was no consensus between the Democratic Party and the Socialist Party how reconciliation had to take place and through what mechanisms. The Democratic Party left the care-taker government in December 1991 and changed the electoral strategy from cooperation and pacts towards social mobilization and confrontation. Henceforth, the initial institutions of the regime change in 1990-1992 were rather inexistent and did not take root. The outcome of the contested agenda of change and the equal balance of power between the two main political parties was the establishment of a hybrid not-fully democratic regime that have led to what is usually termed as a protracted transition in Albania. The regime cycle framework could actually help to indicate the shift towards a more authoritarian regime starting after the defeat in the referendum for the Constitution in 1994 initiated by the Democratic Party, in government at that time. The process of dealing with the past became more polarizing and politicized (Elbasani & Lipinski, 2011).

References:

Alia, R. (1990). Democratizaton of the Socio-Economic Life Strengthens the Thinking and Actions of the People. 8 Nëntori

Alia, R. (1986). Të ngremë më lart punën ideologjike të Partisë dhe frymën e militantizmit revolucionar. Studime Politiko- Shoqërore, 11, 7-29.

Biberaj, E. (1998). Albania in Transition: The Rocky Road to Democracy. Routledge.

Çami, F. 1986. Të mbajmë lart frymën miltante, të zhvillojmë mendimin krijues. Studime Politiko-Shoqërore, 11, 30-37.

Elbasani, A., & Lipinski, A. (2011, 02). Public contestation and politics of transitional justice: Poland and Albania compared. (EUI Working Paper SPS).

Falk, B.J. (2003). The Dilemmas of Dissidence in East-Central Europe: Citizen Intellectuals and Philosopher Kings. CEU Press.

Gregory, P. R. (2004). The Political Economy of Stalinism: Evidence from the Soviet Secret Archives. Cambridge University Press.

Hale, H. E. (2005). Regime cycles: Democracy, autocracy, and revolution in Post-Soviet Eurasia. World Politics, 58(1), 133-165. https://dx.doi.org/10.1353/wp.2006.0019

Hoxha, N. (1986). Veprimtaria shklencore tw pwrshkohet tejembanw nga fryma militante revolucionare. Studime Politiko- Shoqërore, 11, 38-46.

Jowitt, K. (1992). The New World Disorder: The Leninist Extinction. University of California Press.

Kotkin, S. (1995). Magnetic Mountain: Stalinism as a Civilization. University of California Press: Berkley.

Lewin, M. (1989). The Gorbachev Phenomenon: A Historical Interpretation. University of California Press: Berkley.

Lewin, M. (2005). The Soviet Century. Verso.

McFaul, M. (2001). Russia’s Unfinished Revolution: Political Change from Gorbachev to Putin. Cornell University Press.

McCauley, M. (2007). The Rise and Fall of the Soviet Union. Routledge.

Petrov, K. (2008). Construction, reconstruction, deconstruction: The fall of the Soviet Union from the point of view of conceptual history. Studies of Eastern European Thought, 60, 179-205. https://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11212-008-9056-9

Rigby, T.H., & Fehér, F. (Eds.). (1982). Political Legitimation in Communist States. Palgrave Macmillan.

Rutland, P. (1994). The end of the Soviet Union: Did it fall or was it pushed? Critical Review: A Journal of Politics and Society, 8(4), 565-578. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08913819408443361

Szelény, I., & Martin, B. (1988). The three waves of new class theories. Theory and Society, 17(5), 645-667.

Tismăneanu, V. (2003). Stalinism for All Seasons: A Political History of Romanian Communism. University of California Press.

Verdery, K. (1991). National Ideology Under Socialism: Identity and Cultural Politics in Ceauşescu Romania. University of California Press.

Vickers, M. (2001). The Albanians: A Modern History. I.B. Tauris.