By Dr. Taulant Hasa

Abstract

Now, we are stepping into the fourth decade of the ongoing Albanian transition process. It is nearly a decade ago, from the existence of the totalitarian regime. Both periods have remarkably affected the social and economic development of the country. These pillars are considered as the aim of every society, democratic or not, regardless of the perspective, path, methodology, subsequently political intention. The Taliban, according to their political statement, one day after the fall of Kabul at the beginning of August, sought the prosperity of Afghan people, even though under the Sharia law[1]. Similarly, in the constitution of North Korea, as a paradox of the political system, the prosperity of the North Koreans[2] is the purpose of the most terrible regime still alive around the globe. In this regard, political rhetoric, and regimes beyond theoretical definition, typically is perceived as “dogma” or cliché. The European Integration (hereafter EI) has been during the transition the goal of the Albanian political agenda. Even in the darkest moment of transition, EI has been considered as the lighthouse of hope and progress. The EI, undoubtedly, has been a mechanism of modernization to improve and strengthen the rule of law; implement European legislation, and reduce the gap with the most advanced legal framework in the world regarding social-fundamental rights and democratic standards. This paper will try to sum up the factors that have marked the agenda of EI, considering the political cliché as the conjectural factor to diminish this process.Keywords: Transition, integration, Albania, EU, democratization

[1] https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2021/08/22/taliban-historical-rhetoric/

[2] Preamble and Article 2 of the Constitution, https://www.constituteproject.org/constitution/Peoples_Republic_of_Korea_1998.pdf

Introduction

26 years ago, Albania was accepted as the 35th member of the Council of Europe. Back then, the atmosphere was a celebration day. Tens of cars flagging EU symbols paraded across Nation’s Heroes Boulevard, a national symbol, while the Democratic Party in power was trumpeting the membership as a step close to the EU. The enthusiasm might have been perceived as a confusing mechanism under the propaganda mechanism, to promote the idea that the EU was a step closer. Still, almost three decades after that moment, the political message intends to create enthusiasm for the EU integration process, and use this policy as a mechanism to persuade public opinions. EI in Albania is considerably linked to the political agenda and less to public debate. This was a commune observation similar to occurrences in other European countries, but since the spread of Covid-19, citizens are more confident and interested in EU [1].

Back to the argument, the Council of Europe (CE), undoubtedly, represents a liberal view of Europe, “quasi” a spillover and functionalism theory (Hass 1958) after WWII, which targeted the Fundamental Rights, considering the lack of this “chapter” as a condition to breed totalitarian systems. The European Convention of Fundamental Rights is a part of EU legislation enacted after the Treaty of Lisbon in 2009[2]. While its application, is a fundamental part of International Public Law and European Acquis, acquiring consequently an extra-Constitutional Consensus among EU pyramidal legal hierarchy[3]. Albania is one of the most “obedient” countries among CE members to fulfill the European Court of Human Rights rules[4]. But to conclude CE is not EU, even back in that day, the message was to perceive it as similar.

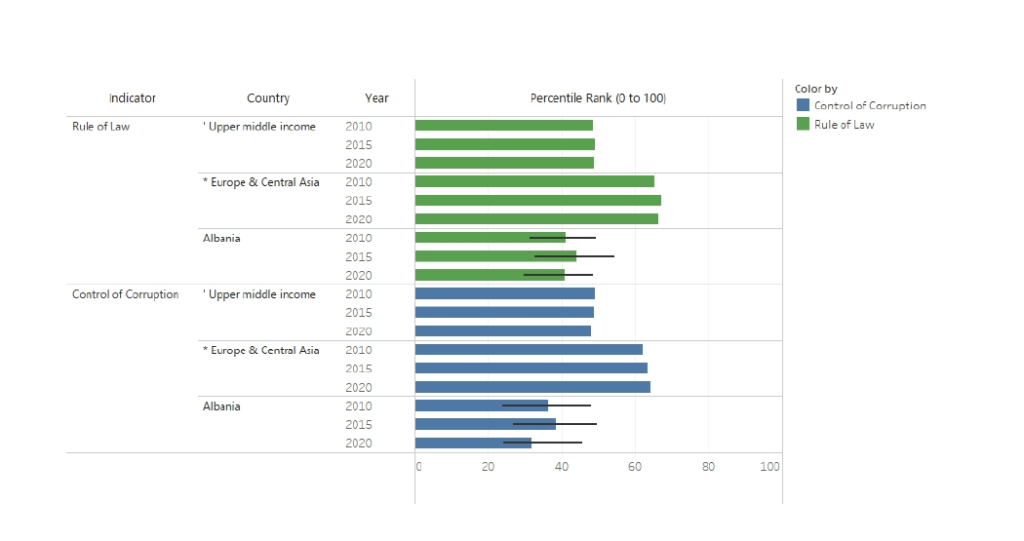

Two years after obtaining CE membership, Albania failed to successfully manage a financial crisis, the most dramatic crisis in the modern history of the country. The crisis of 1997 was a state collapse and a regression to ground-zero concerning the transition process[5].The effects of this crisis were devastating for society, and still, nowadays the aftermath of it is noticeable, principally in the public security sphere and informality. This article will target the division that exists in the social debate over EI. To clarify this, we have to split the EI process into two categories the integral process: including all public policy; and European Membership: which is “solemn moment” and political decision in a moment where European “polity” (Hooghe, Marks 1997) has turned asymmetric and gradually the process to join EU. This article will symbolically analyze arguments that have increasingly caught the public interest to the detriment of political propaganda, and this is a positive turnout for the public benefit. The hypothesis is that when public opinion receives a direct message on European Membership, the “euro-optimism” decrease”. Studies evidence this process in Serbia, Montenegro North Macedonia[6]. EI is in the interest of the actors involved in this process. EU institutions from the geostrategic agenda need to sustain European values within the societies in development to guarantee that European Governance continues to be a gravitational element (Telo 2007). On the other side, national political parties and governments need the EI agenda to back both social and economic development and consolidate their role in international relations.

This article is organized in the following way; the first section is an introduction and conceptualization of what the author is working to deliver; the second section will bring to the argument theoretical approach and an approximation on the study of political transition; the third section summons a view from a theoretical perspective on Albanian transition; the fourth section analyzes the role of the International Community (IC) as an important pillar of transition scenarios; the fifth section introduces to the debate of the EI, and how the political transition has obstructed this process; the sixth section sums up the state of the integration process, and the seventh brings about the conclusion of this process and a hypothesis relating enlargement process in this decade.

[1] https://www.europarl.europa.eu/at-your-service/files/be-heard/eurobarometer/2021/spring-2021-survey/report.pdf

[2] https://www.echr.coe.int/Pages/home.aspx?p=basictexts/accessioneu&c=

[3]Bellamy, R, Schönlau, J; (2004) The Normality of Constitutional Politics: An Analysis of the Drafting of the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights Constellations: An International Journal of Critical and Democratic Theory, Vol. 11, No. 3, pp. 412-433

[4] Violation by states and article of the Human Right Convent, https://www.echr.coe.int/Documents/Stats_violation_1959_2020_ENG.pdf

[5]Bezemer, D. J. (2001). Post-socialist financial fragility: the case of Albania. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 25(1), 1–23.

[6]Eurobarometer findings in Serbia, North Macedonia, Albania. https://europeanwesternbalkans.com/2019/08/06/serbia-the-only-wb-country-with-more-trust-in-the-government-than-in-the-eu/

The theoretical background of political transition

The political transition is related to the democratic maturity of societies. According to John Rawls (1971), its success remains deeply in the interaction between state and citizens. Governors have to rule legitimately, democratically, transparently and citizens to be reasonable and oblige rules. In this context the concert of “comprehension” takes place, considering states, spaces where all have to be benefitted. Rawls brings out four elements in his political philosophy judgment that characterizes the progress of societies; political culture, efficient and continuous institutions, liberal tradition and religion tending through Christianity, and its influence on the liberal constitutions. Protestantism and Catholicism tradition are perceived as cultural factors that lead to democratization because their traditions are based on individualism, tolerance, and secularism. Culturally, these elements provide a better understanding of peaceful competition and power alternation[1].

For Weber (1920), the state is a relation of domination throughout legitimacy. The state represents a complex nature and is used to designate the form of political organization and the public powers of a political community. This applied to different social realities in different geographical, demographic, economic, or social aspects. The state is a necessity of civilized societies (Mann 1997) and is frequently linked with liberal democracies and the state itself is a product of a free exercise of will. According to the World Bank, the most developed societies are liberal democracies[2].

The course of political and regime transitions is crucial to determine the efficiency of structural reforms, regarding the social-economic development and rule of law. Several elements influence the state of transition; the type of regime previous to the transition, the character of new leaders, elections, non-state actors, political parties, ICT (Information and Communication Technologies), and international actors. These elements have to do with structural factors and according to Lowenthal and Bitar (2015), usually are linked to the studies of East Europe after the fall of the Berlin Wall. In other scenarios, in Africa or South and Central America, the role of the military forces is decisive to determine the political transition.

According to Fukuyama (2016), political transitions are characterized by three elements; mobilization to oust the old regime, free elections, institutional capability to provide services, and implementing public policies. The second and third element according to its judgment tends to not succeed in the political transition, due to the lack of experience. The new political elites that replace the old regimes are very important to manage the fresh enthusiasm that characterizes periods post-regime. They handle the illusions for change, and people have high expectations on how this new political power meets their demands. Their success is narrowly linked with the efficiency of social-economic development and the state of the rule of law. Last but not less, international actors are crucial to force democratic change in those cases where transition tends to follow liberal values generally Western Democracies.

Usually, the political transition period is associated with an economic crisis. Studies show how this indicator usually makes more unstable this process (Gasiorowski 1995 and Przeworski 1996). The volatility during the transitional process does not create a solid environment to strengthen democracy and inclusive economic development. Equal economic redistribution and high income are precious assets to improve a representative democracy and the rule of law. According to the World Bank, this is an indispensable variable for prosperity.

[1]Fagan. A and Kopecky, P (2017) “The Routledge Handbook of East European Politics” Abingdon, Routledge. Pg 15-20

[2] Human development index data, https://databank.worldbank.org/Human-development-index/id/363d401b

Usually, the transitional process triggers inequality, a corruptive privatization process[1], informality, and a lack of fiscal pressure among elites. According to Acemoglu and Robinson (2001), nondemocratic societies are dominated by rich elites. These authors underline the fact that at this stage countries are prone to a volatile fiscal system that allows new elites to oppose democracy. The figure of “tycoons” and “oligarchs” is very present in these scenarios. During the political transition, Russia saw how numerous billionaires emerged to the detriment of public assets, also east European Countries[2] saw how old elites during the communist regime were very active to participate in the privatization process, influencing to increase unequal distribution of public wealth and gain political influence[3].

[1] The Government of Albania in 1992 applied a similar massive process of privatization as in the Czech Republic or Poland, despite that a country was far behind on economic development and rule of law standard to guaranty an equitable process. For more info see, Hashi, Iraj&Xhillari, Lindita. (1999). Privatization and Transition in Albania.Post-Communist Economies. 11. 99-125.

[2]For more info see the case of Czech Republic, “Elites in Central-Eastern Europe”, pg 64-66 https://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/budapest/04578.pdf

[3]Bloomberg research on the figure of oligarchs in East Europe https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2019-12-21/how-east-europe-s-billionaires-rose-from-the-fall-of-communism

The post-totalitarian process as a hybrid regime

Political activity is the executive base of democracy. Those in positions of the governor have direct responsibility for the development of the country. Political transitions after the fall of totalitarian regimes produce new political and economic master elites. The integrity of elites is an important factor from the perspective of human development theory (Welzel, Ingelhart, 2001). The transitions process creates an ance among political and businesses able to hinder aspiration of the liberal process and alter democratic and economic opportunities. Often these elites are still seeking to control the public sphere even after the old regime has collapsed. This tendency is narrowly linked with the ideology, legitimacy of power, and charisma of its leaders and how they perceive democratization processes. Post-totalitarian periods are characterized by limited social-economic and institutional pluralism (Acemoglu and Robinson 2001). Leaders tend to check party structures, legal and administrative procedures, political parties’ internal democracy and state bureaucracy, and other branches of power like the judiciary system. In other words, post-totalitarian periods tend to be “single-mind structures”.[1] One of the most notable effects on the social structures is the growing gap among social classes and potential economic crises, on the other side, it creates more economic opportunities, which not necessarily can be reflected in lower unemployment. One of the facets at the social level that jeopardize the evolution of transition is the high rates of corruption which lead to the “culture of corruption” eroding public services. Societies with low incomes and with certain degrees of collectivism and exposed to traditionalism are prone to high rates of corruption. For Javidan Mansour (2007), who led the World Bank project, GLOBE[2], the culture of corruption is a phenomenon in those situations where public administrations politically polarized offer an unprofessional quality of services and where public employees are governed by poor professional training[3].

[1] Council of Foreign Policy provides a special edition from the journalism perspective on the ongoing transition process in the world. For more information; https://www.cfr.org/politics-and-government/political-transitions

[2] For more information https://globeproject.com/publications

[3] Freedom House report in 2020 considers the country according to the public perception as highly corrupted. 85% of citizens consider this phenomenon widespread across the country and public administration. https://freedomhouse.org/country/albania/nations-transit/2020

The previous paragraphs are part of the vast literature on the study of the transitions process and reflect this pedagogy on the post-totalitarian period and transition process in Albania.[1] Theoretically, this period can be considered as a mirage of what political transition have experimented with after the fall of the communist regime. Among many observations, that from a personal perspective can surge, is evident how these “pathologies” have affected this process; how ex-communist bureaucrats at lower levels participated actively in the democratization processes, affecting the quality of it; how leader`s personalities have conditioned the outcome of reforms, the democratization of political parties and independence of institutions, and how inequality has been a social inquietude.

All these post-traumatic political conditions can not necessarily lead to the fail of the state. It can worsen and affect the democratic perspective, cause a debacle of liberal standards, and affect public policy, but what makes the difference is that the lack of political debate and the immaturity of considering politics as private territory not as a public asset, lead to a misunderstanding of the democratization process. All these elements, “river-mouthed” the first part of political transition in 1997, causing the collapse of the whole pillars of the state[2]. The GDP of the country fell by 8%, which altered furthermore the poor economic-social conditions still pertinent after the fall of communism[3].

It is not the aim of this article to categorize the reasons for this collapse. However, from the retrospective, we have various indicators to build our personal opinion on how post-totalitarian societies can at least avoid this drama. During this period, domestically, government and other state actors were unable to promote security to citizens, preserve the legitimate monopoly of force, and offer public services. This crisis above all shows the failure of the political class, and the deprivation of politics as a tool to find solutions, overcome obstacles, and prevent conflicts.

Regardless that since the fall of communism, a liberal constitutional system and democratic form were adopted; the ability to guarantee a legitimate monopoly of the rule of law[4] was eroded by the indoctrination of the public policy sphere[5]. Last but not less, the tragic events in 1997 obstructed a historical chance to deliver a peaceful regime change, and implement state vision, instead of personalizing the power and extending the totalitarian methodology to a liberal system, which is also one of the indicators of the society post-totalitarian, but not necessarily a “habitat” to darken the ambitions for a more prosperous society.

[1] The last report of Freedom House considers the country partly democratized, worsening in all the indicators that this think tank used to measure Nation in Transits

[2] This article explained in details the reasons of the financial collapse in Albania, including also economic data before that period. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/1999/wp9998.pdf

[3]The Conflict Studies Research Center, https://www.files.ethz.ch/isn/43795/03_Aug_11.pdf

[4]One of the indicators that IMF measures the relations between rule of law and economic development is the percentage of the tax revenue compared to GDP. Albania during the 90-s has one of the lowest in East Europe, even lower than Moldavia. Tax revenues were only 16% of GDP in 2001, Stabilization Policies and Structural Reforms in Albania Since 1997 : Achievements And Remaining Challenges, pg 18

[5] Human rights in Post-Communism in Albania, Human Rights Watch publication March 1996, https://www.hrw.org/legacy/summaries/s.albania963.html#TOC

International factor as babysitting instrument

As mentioned previously, one of the facets of the transitions is how the International Community (IC) assumes, recognizes, and guides the democratization process. Following the end of the cold war, the promotion of democracy and international assistance to strengthen liberal processes became a key element of foreign policy. On the European level, this diplomatic evolution was reflected in the Treaty of Maastricht. This phenomenon was extended also to the non-governmental sphere, giving rise to many international initiatives from the liberal perspective mostly west democracies. It was perhaps this moment to consider democracy as a global aspiration, and in this context, IC sought to extend the wave of democratization which gave somehow space to globalization. This element and how the IC participates in the “share” of sovereignty fits under the second wave of neo-functionalism, and constructivism, linked with the fall of the Berlin Wall (Rosamond 1999) (Moravcsik 2001). The participation of IC in the case of study has sociological nuances. This factor has acquired a controversial condition in the transition process, consolidating its role as a decision influencer on foreign policy, constitutional and economic reform, and political debate.

The story of Albania during the XX century is closely related to the presence of these elements. This has been a condition to consider the course of the transition process and democratization. Furthermore, IC has been a necessary element to strengthen institutional efficiency and lead legal reforms[1]. It is not the aim of this article to reorder the historical process linked with the role of the IC. However, we can agree that the period after 90-s is quite interesting to evaluate how this element has followed the Albanian transition. We will underline this presence from a theoretical perspective, not a historical one.

It is quite common in the Albanian political debate to assume that the “International Factor” as routinely is so-called, is a conditional must. This conditionality has been an active conjectural actor in the political crisis, legal reforms, etc. This happens not only on the central level, including political parties and institutions that carry out important reforms but also on the periphery level. Many regional governors seek international “remedies” through diplomatic representations, to intermediate institutional or political conflict. Also, many citizens address international presence in the country to claim rights and justice, which is reasonably paradoxical. From a personal perspective is fairly bizarre that some institutions at all levels flag US and EU symbols, despite that we are not part of the EU, neither an associated state of the USA. This might be considered a violation of the constitution, which determined what our national symbols are. In this context, seems that citizens are socialized with the “International Factor” considering this stage as a necessary condition to make the reforms and democratic process, appear quite acceptable for the “legitimacy” of it. This phenomenon is a handicap of the transition process.

The IC has been a promoter of good governance, democratization, and Europeanization. There is a broad consensus on how this element has maintained at least the democratic aspiration alive, which is the lowest reclaim on the pyramid of the democratization process. Aspiration is an emotional inquietude while the democratic process requires an imperative institutional performance, rule of law, and sustainable economic development, among other factors[2].

Back to the argument, there are plenty of reasons to consider the EU as an extra-IC actor, and an important factor in overlapping national consensus, which includes legal imperatives in the case of Albania. The absorption of EU Acquis is part of this trend. We cannot reflect on the EU as a mere IC but as a third way of legal and economic reformation for the country, after considering the role of parliamentary and executive governance as the first two ways of this reformation. EU and the USA are the most exposed international factors in this process. The role of the EU tends to be more structural, involving legal imperatives, which is reflected in the process of EI mostly since the start of the Stabilization and Association Process. In the USA case, there are geostrategic and historical ties that characterized the conjectural share-power process. We have witnessed very frequently how this conjectural element has been a crucial factor to put in many occasions the country on the track of political agreement and force legal transformation and institutional strengthening.

The EU membership has been to some degree a stabilization factor that assists the transformation process. Nevertheless, the increasing debates between the Member States have notably eroded the ability of European governance to reduce the gap with, WB. The background of the EU as a crucial factor to speed political transition in Albania has experimented with a metamorphosis. Its role as a quasi-state player in the democratization process has been intensified since the launch of the Stabilization and Association Process in 2000. In the 90-s the EU’s presence in the country was focused as a diplomatic player, observing the democratization process more than participating in it. This has been also the role of the EU as an international actor, characterized by its softness, and later on as a normative power rising its influence as an important actor on world governance. The association and later on, the membership process turn the EU into an imperative element of transformation. Before this stage, the EU reflected more diplomatic participation when it comes to bilateral relations, and this was the disposition of the EU`s presence in Albania in the 90-s.

[1] Nearly 45% of the IPA financial assistance 2016-2020, targeted the component of “Assistance for Transition and Institution Building, which includes “ Democracy and Governance ” and “ Rule of Law and fundamental Rights”; for more information see, https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/enlargement-policy/overview-instrument-pre-accession-assistance/albania-financial-assistance-under_en

[2]Bertelsmann transformation index (BTI) uses democratization, governance, and economic transformation indicators to evaluate the countries in process of transition or transformation. For 2020 Albania ranked among countries with the lowest transformation index for the East and Southern Europe area. For more info see https://atlas.bti-project.org/1*2020*CV:CTC:SELALB*CAT*ALB*REG:TAB

European Integration as a “metaphysical” state of play

According to Hass (1958)[1] one of the theoretical founders of functionalism and European policy through “Spillover” mechanisms, EI is a process in which political actors in different national contexts are persuaded to shift their loyalty, expectations, and political activities towards a new center, whose institutions own or claim jurisdiction over pre-existing national states. The outcome of this process is the economic integration, and a new political community, superimposing the existing ones. The process of EI has guided states towards a new form of regionalism based on its singular model of governance. This model has pacified and unified Europe, socially, economically, politically and has been a mechanism to face the challenges of globalization. Europeanization, Integration, and European governance are not compatible with the “Westphalian state” and being a member of the EU or being in this process entails a slow and rational change towards shared sovereignty.

The EI politically and Enlargement Policy technically have turned Europe from a historic and geographic point of reference into the larger democratic and prospered area of the world. In terms of human development and democratic quality, there is no doubt that the EU is a leading project for the whole of humanity, providing peace, economic development, and the highest indicators in the world to protect human and fundamental rights.

Since the fall of the communist regime, Albania has prioritized EI as a public policy paradigm. EU scheduled the first stage of this national priority as a diplomatic player to assist Albanian transition and to help social-economic recovery. Both sides in the 90-s established a rapport characterized by diplomatic and commercial ties. The first agreement between Albania and EC was signed in 1992. It was a trade and cooperation agreement which among others allowed Albania to apply for the PHARE[2] funds, a program launched in 1989 to support central European countries to join the EU[3]. Since then and more firmly when the SAA entered into force, the EU has been a singular and a structural player of the public policy, which is the highest distinction to carry out the progress on the way of EI but also lead democratization and modernization of the country.

One of the facets of this process is that the state of play of relations is based on three elements; how the country perceives EI, how prepared is to implement EU rules, and if the EU is politically ready to advance on the membership perspective. We mentioned previously that EC[4] launched in 1989, an important economic program to support East European countries to join the EU. This economic program was planned before the fall of the Berlin Wall but after the Solidarnost movement in Poland. In this context, the EU had a vision for the future, to enlarge the single market and start a journey to move from an economic union to a political one. On the other hand, despite that Poland or Hungary, lacked institutional and political conditions to start negotiation accession back in the 90, EI was perceived as a cultural-based process, which turns to be a political asset to sustain the integration process. From the EU perspective, the East Enlargement was a rational choice to strengthen the single market and extend European Governance. In this context, this can be considered a space where all actors involved benefit from this relation and create a political habitat to make possible an EU membership.

In the case of Albania, in the 90-s, EI was perceived as a visionary project without considering the normative burden of the process. The state of development and the democratic maturity was not at the level to provide a solid economic relation or association. Politically EU did not consider that the state of the play was sufficient to indulge the Member States (MS) to see the membership of the country through the lenses of the European vision, instead of a normative burden. Moreover, economically and the preparation of public administration was not in a condition to provide more than a mere trade and humanitarian aid partnership. The GDP of the country between 1991-1993 fell by 48%, industrial production by 90%, and budgetary deficit by 68% of the GDP. Regardless that after 1990 world economy entered into recession, the Albanian case is the most controversial. According to the World Bank, only Iraq and Lebanon experimented a higher recession than Albania, respectively 64% because of the War of Golf, and 49% due to the civil war in the country.[5]

This perspective still lacks on the vision of MS. Albania is a controversial case on the way of EU membership. Regardless, that during the transition period existed opportunities to advance as an independent player on this path, the country had a lame dynamic to reduce the gap with the EU. Albania did not undergo the structural “pathologies” of the Western Balkans like ethnic confrontation, war, or regional disputes. The country was on the fate of its own to establish a European agenda and be at the forefront of the process as a candidate country, since the first EU-WB summit held in Thessaloniki in June 2003. To exanimate the state of the play of the ambition to be part of the EU, all the variables induce the lack of political maturity to perceive the integration process beyond the lenses of political-archaic vision and personal interest. This process can be observed from different perspectives but there is a common sense that the political class in the country failed to guaranty sustainable progress and establish an overlapping consensus. This is a minimum criterion to consider politics as a tool in service of the public policy, a space where all citizens must be benefiting.

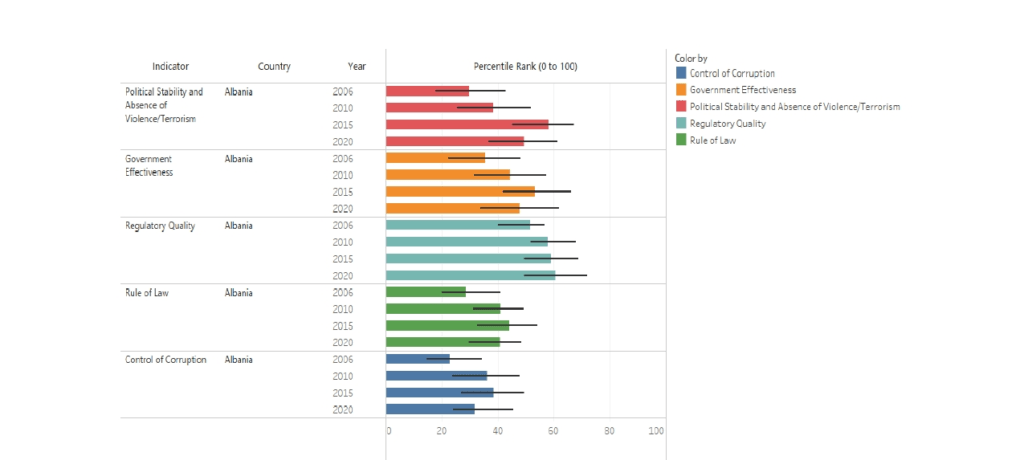

Since the SAA enters into force EU commission has evaluated the country yearly under Progress Report. The common denominator of these reports remains on the fact that the EU considers the political class not in the condition to face integration process and all branches of it; implementation of EU Acquis, political agreements to face structural reforms, the transformation of Public Administration, fight against corruption, and criminal activity and strengthened of the rule of law, etc. Despite that Albanian governments consider EI as the gear of the whole public policy, including also foreign policy as part of public interest, is not in the condition to optimize the European aid. EI is a scenario of the political debate, parliamentary and overwhelming legislation process. On the other hand, the EU commission is the watchdog of the whole state reformation. Even that Albania is not a member country, we have reconsidered national sovereignty under the rational choice to coop with the requirement of this process.

[1]Haas, E. The Uniting of Europe: Political, Social, and Economic Forces 1950-1957. Stanford: Stanford University.

[2] https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/MEMO_98_89

[3] Background of the technical relations EU-Albania https://ec.europa.eu/neighbourhood-enlargement/enlargement-policy/negotiations-status/albania_en

[4] European Community before changing the name to European Union.

[5]For more information and to compare data see World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?end=1991&start=1988&view=chart

EU enlargement: many sticks, fewer carrots

Metaphorically on the EU policy, the stick is paraphrased as the meaning for conditionality, reforms, regulatory burden, etc, related to the integration approach. While the carrot to sustain EU governance in Western Balkans since the first EU-Western Balkans summit in Thessaloniki in June 2003. The social progression and human development spurred among others by the multidimensional presence of the EU in the area rationally have shoved WB on the track of Europeanization. By this, we understand a socialization process with EU values and adaptation with European laws. This certainly will happen despite WB membership and is an ongoing process. WB is too small to resist EU governance, representing less than 1% of its economy and trade flows. EU is the biggest FDI (Foreign Direct Investment) in the area, the biggest trade partner, the most important financial donor throughout all phases of IPA (Instrument of Pre Accession), and also a regional policymaker in the area.

During the last summit, EU-WB, in Slovenia, we expected a deadline over the first intergovernmental meeting to discuss when North Macedonia and Albania will start to negotiate 35 chapters and probably more than 1000 benchmarks[1]. The starting of the negotiation process takes place in three decisions. First, a political statement of the EU Council to start the negotiations, second, the EU Council of general affairs decides the date for the first inter-governmental meeting, and the third, EU Commission delivers a guideline on how to do so. In this process even that the EU Parliament has too much to say is not being a relevant player to face the political volatility of EU Member States (MS). In all these stages aggregated interest by MS, can block the negotiations. This is not included in the Copenhagen Criteria but is used by MS to strengthen public diplomacy, and force candidate countries to accept national preferences, which usually has to do with historic background or bilateral relations.

The mechanism of decisions making of the Council, using the power of veto ignoring technical recommendations of the Commission is making less resilient the process, and “nationalizing” the enlargement policy. In February of 2020 EU[2]proposed to change the methodology of enlargement, stressing out the dynamic of negotiations of the 35 chapters. In this regard, the country’s part of the negotiation process will need to close the chapters related to the reform of public administration, rule of law, and economic criteria, before continuing with other clusters. According to the EU Commission, rule of law will be the last chapter to close, which means that during this decade the system of Justice will be under the strict observation of the Commission. It seems that the Commission does not want to face the same legal debate as is currently happening in Poland[3], Hungary[4] but also in Bulgaria and Rumania[5]. These chapters have paramount importance not only for the progress of the process but also for society per se. This dynamic might extend more the negotiation process and alter the enlargement fatigue on both sides.

We mentioned before how defenselessly are WB on public policy to attend 27 governments. First of all, this area faces structural challenges implementing EU Acquis, attend the burden of the EU Commission during the association process, following the guidelines on regional policy including intra-regional relation and stabilization in those areas where is still needed, for example, BiH and Kosovo. Next year will be crucial for this policy. French elections can probably affect this process, and can even be an argument on the campaign. The new coming German government has not clear yet what visions have for the enlargement and what to do with the Berlin Process blue moment. On the other side, the EU is on the brink of challenges like; energy crisis, high inflation rates, post-pandemic recovery, the green economy “revolution” and how will affect the economic structure. From this perspective, is difficult for the EU to find an opportunity to spill over on the enlargement process.

Economically EU doesn’t need to enlarge herself to bust competitiveness and growth. EU doesn’t need either to make more attractive its governance. However, the EU needs to enlarge its perspective on how will adapt herself in post-globalization and how will attend to global challenges including security and defense. The current enlargement process is a new experience for the EU. Peace and stability are cornerstones for EU integration, interior market, and how relevant the EU wants to be in the world. This exam and the balance of opportunities will establish a different agenda for enlargement. The last summit had the chance to be a turning point to stop the integration fatigue that WB are witnessing since the previous Commission under the Juncker presidency, but it only repeated the rhetoric of institutional commitment to enlarge the EU, without offering details[6].

This dynamic might add more fatigue to the subjects of this policy. Serbia is being blocked on the way to negotiate more chapters, facing Kosovo normalization and recognition issue. EU is using a confusing strategy hoping that Serbia will do so by negotiating technical questions like taxation, environmental challenges, monetary policy, or even general issues under the 35-the chapter. Governors in Belgrade are not willing to make a historical decision by negotiating technical issues with the EU, which does not guarantee membership. They might do so if they have a clear membership perspective soon as the political decision among 27 will allow Serbia to be a member no later than 2025. EU is forcing Serbia for recognition at an early stage of membership perspective. Serbia might recognize Kosovo only if is a member and to do so a clear perspective is needed. Furthermore, Serbia has becomea financial and economic anchor of the Chinese investment in Europe and soon might be extended to the defense industry and policy[7].

IPA program in the area is not attending public policies that can turn WB into a loyal partner. Enlargement fatigue is being now turning into European integration fatigue from a WB perspective. This summit had paramount importance to keep the integration pulse alive and clarify what vision EU has for the area and enlargement perspective and in this context added 9 billion euro to the Economic and Investment plan for the area. The total amount that the EU promised for the area, almost 40 billion euros, is nearly half of the area’s GDP. Undoubtedly is a significant amount to support economic development and somehow the economic recovery as a result of the Covid-19 crisis, but the pessimism among Balkan countries is turning to integration fatigue.

Despite this financial support, the lack of political commitment will soon turn the area into an easy area eager to anchor economic and geostrategic interests for other international emergent actors. Membership is a political decision of MS. Hence, the EU Commission might propose different ways of cooperation extending perhaps the EEA (European Economic Area) zone to WB, which means four EU freedoms[8] and participation on the single market, but not a seat on the EU decision making. WB is progressing in this direction, developing initiatives as Open Balkan. This is not a plan B to the non-enlargement option but a mechanism that is pressuring the EU to be more credible on enlargement policy.

[1]Estimation of the author

[2]For more information see, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/de/qanda_20_182

[3]Regardless than exists a vast jurisprudence over the supremacy of EU law, Poland Constitutional court decided that EU Law remain at a lower level than Poland Constitution, putting both parts on a legal crisis https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/speech_21_5361

[4]https://www.euronews.com/2021/07/15/eu-begins-legal-action-against-hungary-over-anti-lgbt-law

[5]Romania and Bulgaria are under the Cooperation and Verification Mechanism to coop with the EU requisites on the Rule of Law; https://ec.europa.eu/info/policies/justice-and-fundamental-rights/upholding-rule-law/rule-law/assistance-bulgaria-and-romania-under-cvm_en

[6]Final declaration after the summit EU-WB, 6 of October, https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2021/10/06/brdo-declaration-6-october-2021/

[7]For more information see, http://www.ras.gov.rs/uploads/2020/10/eng-opportunities-for-investors-from-china-ras-1.pdf

[8] Movements of persons, capitals, goods, and freedom to establish and provide services.

Conclusion

This article aimed to bring to the debate of the transition process and EI, few reflections that have characterized this period, facing theoretical perspective and the results of this policy. Transitions processes measure the pulse of societies and might be historical opportunities that create the habitat for progress. In this article, we mention a few variables which make possible normal and equitable progress including the social-economic sphere and democratization. In the case of study is quite assumable to distinguish from several periods and processes how the political class fails to put on the rail of integration a historical ambition, to be part of the EU under rational space of time, as much as the conditional burden of European rules allows a country to be part of the union. Albanian society has never doubted the rational choice of assuming European values as part of their identity, but this social and cultural perception has crashed on the wall of an archaic model of doing politics, an extension of the version of anarchism and folkloric acuity, quite far away from contemporary political discourse.

This handicap has harmed the ambitions for a more prosperous society and the historical chance to be at the forefront of European integration in the southeast of Europe. Institutionally we have assumed this goal and positioned the enlargement policy as a national imperative priority, but considering how the political class has managed this paramount ambition, we can deduce that this national preference is more likely to be a declaration of intention and less an integral process of good governance.

On the other hand, this promise was launched as a political project to strengthen peace and security in this area, but now that Western Balkans seems to be more mature on ethnic connivance and regional policy, the EU is missing a fable to keep its promise. The MS, not EU institutions, as the protagonists of decision-making, since the big enlargement of 2004 have reconsidered the dynamic of this process. From the lenses of the balances of cost-opportunities, EU Member States does not find an inspiration on national and European politics to have a vision of the enlargement beyond the pragmatism that causes the lack of this process on security and stability in Europe. This enlargement is a new experience for the EU seeking a security approach, but as long as the EU considers the area as a security provider, will not move forward on the enlargement process. This is part of contemporary EU pragmatism.

The union lacks the political motivation to finish the process, and this will be the gameplay for this decade. Undoubtedly, back in the 90s, we lost a unique chance to build a better perspective when the enlargement policy was launched as a visionary project and less as a normative burden. Probably, this might be considered as one of the transition “sins”.

Bibliography and other sources

Acemoglu, D. & Robinson, J. A. (2001) A Theory of Political Transitions.The American Economic Review, 91(4), 938–963.

Abrahams, F. C. (2015). Modern Albania: From Dictatorship to Democracy in Europe. NYU Press.

Bitar, S, Lowenthal, A.F., Hagman, L. (2015). Democratic Transitions: Conversations with World Leaders. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Brainf, M. (2011), Integrating Balkans .Conflict Resolution and impact of EU enlargement, Taurus, Nueva York, pp. 145-147.

Delanti, G. Rumford, C. (2005). Rethinking Europe: Social Theory and the Implications of Europeanization. Routledge London, pg. 3-25.

Fagan. A and Kopecky, P (2017) “The Routledge Handbook of East European Politics” Abingdon, Routledge.

Fukuyama, F. (2020). 30 Years of World Politics: What Has Changed? Journal of Democracy, 31(1), 11-21.

Goetz.K, (2000). Europeanized Politics. European Integration and National political system. West European Politics. Edition Especial. Vol 23. Num 4.

Hashi, I &Xhillari, L. (1999).Privatization and Transition in Albania. Post-Communist Economies.Pg 99-125, Staffordshire University, 1999

Hooghe, L & Marks, G. (1997). The Making of a Polity: The Struggle Over European Integration. European Integration online Papers (EIoP).1. 10.2139/ssrn.302663.

Inglehart, Ronald–Christian Wetzel (2005) Modernization, Cultural Change and Democracy. The Human Development Sequence. Cambridge UP, Cambridge

Rawls, J, (1971). A theory of justice. Cambridge, Massachusetts :The Belknap Press ofHarvard University Press,

Resick, C & Deuling, J & Dickson, M & Hanges, P. (2009). Culture, corruption, and the endorsement of ethical leadership.Advances in Global Leadership. 5. 113-144.

Somers, M. (2007).The Political Culture Concept: The Empirical Power of Conceptual Transformations. Sociological Theory, American Sociological AssociationVol. 13, No. 2 pp. 113-144

Schimmelfenniget, F (2002) “Costs, Commitment, and Compliance. The Impact of EU Democratic Conditionality on the European Non-Member States,” EUI Working Paper RSC 2002/29 58

Telo. M., 2007/ European Union and New Regionalism: Regional Actors and Global Governance in New regionalism / Ashgate England, pp. 12.

Waltz, K, Rosamond, B, (2000) Theories of European Integration.Houndsmills: MacMillan, pp. 132.

Weber, S. (1995). “European Union Conditionality.” In Politics and Institutions in an Integrated Europe (B. Eichengreen et al, eds.). Berlin: Springer-Verlag, pp. 193–220.

Welfens P.J. (2001), Stabilizing and Integrating the Balkans: economic analysis of the stability, Heilenberg, pp. 32-36.

Zoukui, L. (2010). EU s Conditionality and the Western Balacans Accession Road.Jouranl of European Persepctives of the WB, VOL. 2, pp. 79-98.

https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/7c2fa8bd-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/7c2fa8bd-en

Albania: From Isolation Toward Reform, INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND Washington DC September 1992 link, https://www.elibrary.imf.org/view/books/084/00201-9781557752666-en/00201-9781557752666-en-book.xml

Albania : Income Distribution, Poverty, and Social Safety Nets in the Transition, 1991-1993; IMF Library, link https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2016/12/30/Albania-Income-Distribution-Poverty-and-Social-Safety-Nets-in-the-Transition-1991-1993-1315

https://www.imf.org/en/Countries/ALB#

https://data.worldbank.org/country/AL

https://freedomhouse.org/report/nations-transit/2021/antidemocratic-turn

https://data.worldbank.org/country/AL

https://bti-project.org/en/index/governance

https://ec.europa.eu/info/policies/eu-enlargement_en

https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_21_5275

https://www.wbif.eu/wbif-projects

https://www.echr.coe.int/Pages/home.aspx?p=reports&c

http://visionofhumanity.org/app/uploads/2018/06/Global-Peace-Index-2018-2.pdf

Dr.Taulant Hasa is a visiting fellow at London School of Economics and Political Science. He holds a PhD in European Studies and Governance from the Complutense University of Madrid and his research interests focus on the EU Governance and the Enlargement Policy towards Western Balkans.