By Albert Rakipi*

On July 1, 2016, at the inauguration of the massive Osman Gazi Bridge, Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama appeared as a passenger in a Turkish presidential limousine with President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan in the driving seat. The Albanian prime minister, the guest of honor and the only foreign guest, sat in the dignitary’s back seat, radiating a triumphant smile, as he tried to be attentive to the conversation led by the special driver.

Does the fact that the Prime Minister of Albania was the only foreign guest at the inauguration of the Osman Gazi Bridge have any meaning? Of course, there must be some significance as official channels in Ankara and Tirana distributed the video and news before the official ceremony was even over. Even more importantly, it is clear there was meaning in the President of Turkey himself coming out to greet the Albanian guest, even taking on the driver role.

Those who are most enthusiastic and supportive of the foreign policy of the government of Mr. Rama read the scene depicted above as proof of the special relations between Albania and Turkey, thanks to the excellent personal relations that Mr. Rama has managed to build with President Erdoğan.

For skeptics and critics, the scene was more proof that Albania is increasingly sinking into the orbit of Turkey, distancing from Europe. Some would go as far as saying Tirana has already handed over its foreign policy’s driving seat to Ankara. A more realistic explanation can and should be found somewhere between these two extreme positions in the ongoing debate on contemporary Albanian-Turkish relations.

The very fact that the debate about these relations has built and continues to build two conflicting narratives suggests the necessity to have a critical analysis of these relations — and their future in particular.

Albanian-Turkish relations are unique — first and foremost due to their strategic character when it comes to defense and security issues. These relations have always been strategic in the post-Cold War environment, and Turkey has played a balancing role in the geopolitical setting of the troubled Balkans. Having just emerged from communism as a failed state and lacking the capacities and abilities to defend itself under the threat of being involved in the Yugoslav wars, Albania based its defense on a close relationship with Turkey, in addition to its strong ties with the United States.

But Albania-Turkey relations are not strategic only because of certain historical events, such as the end of the Cold War or the disintegration of Yugoslavia. In Albania’s national security equation, Turkey plays a balancing role vis-a-vis Albania’s southern neighbor, Greece, which has historically had territorial claims based on what it calls “Vorio Epirus.”[1] So ingrained is this perception of the danger coming from its southern neighbor and the necessity of balancing it out with Turkey, a rival of Greece, that it continues to linger today even though all three countries are members of NATO.

Second, the relations between Albania and Turkey are also unique due to religious-cultural similarities and, at the same time, the differences that set up clear cultural boundaries between the two peoples.

Third, the relations between Albania and Turkey since the end of the Cold War are unique on another level. Turkey has been neutral toward Albania’s domestic policies. For Turkey, but also for Albania, it has never been important who was in power in Tirana or Ankara. Since the fall of communism in Albania and the new beginning of relations between the two countries, Turkey has never shown a preference for political parties in Albania or for particular leaders who have ruled Albania for almost three decades now. Ankara has never intervened in Albania’s internal political game to support political parties, or particular political leaders. Likewise, Turkey’s foreign policy towards Albania has not been influenced by the ruling political parties or by the ideologies they have represented. Although there is a perception that the Socialists in Albania have been more preferential in their relations with Greece while the Democratic Party has preferred Turkey, Ankara has pursued the same friendly policy and developed relations without being influenced by whether the Socialists or Democrats were in power.

Another almost permanent characteristic feature since the fall of the communist regime in 1990 is that Albanian-Turkish relations have developed linearly without ups and downs, without contrasts or reversals, something truly unique given the fact that Albania-Turkey relations are in a way postcolonial relations.

Last but not least, although Turkey is not Albania’s top economic partner, economic cooperation with Turkey is a strategic component of relations if we take into account the fact that Turkish investments are concentrated in energy, banking, infrastructure and telecommunications.

But what has led to the discussion over these relations splitting into two distinct and conflicting narratives over the past eight years? What has changed in these relationships, which for almost three decades had developed in a linear way? Is Albania losing its independence in foreign affairs under the influence of Turkey? Does Turkey continue to be neutral in Albania’s domestic politics? Is Turkey revising its foreign policy toward Albania? Is Turkey trying to turn Albania into an area of its influence as part of what is seen as a Neo-Ottoman policy in the Balkans? Is Turkey increasing its influence in Albania at the expense of other countries with which Albania claims a strategic relationship? Is Turkey an alternative to Albania’s hopes of joining the European Union? Last but not least, is Turkey trying to cross the cultural boundaries that exist between the two peoples based not only on cultural, religious and Ottoman heritage? The following chapter aims to answer the above questions.

Albanian-Turkish Relations during the Cold War

In general, Albanian-Turkish relations during the Cold War were poor. Before WWII, a Memorandum of Friendship was signed between the two countries in December 1923, one of the first agreements that Albania signed with foreign countries. More than a friendship treaty with the relevant instruments to develop cooperation and friendship, the memorandum was a demonstration of the political will of both countries. In the case of Albania, it was another step in consolidating its sovereignty in an unfriendly regional and international environment — to be accepted as a new state in the Balkans with the territories of which all its neighbors had claimed and continued to claim. The reason for the very sporadic and unsubstantial relations must be sought, among other things, in political instability and internal conflicts in the state-building process, as well as the very backward agrarian economy of Albania.

For almost two decades after the end of World War II, Albanian-Turkish relations were almost non-existent, excluding a small episode that took place at a distance, albeit one that was important. Thus, in December 1955, Turkey supported Albania’s membership in the United Nations, despite objections by other countries, including neighboring Greece. Albania responded with the same gesture a decade later, in 1965, when it backed Turkey in not recognizing Cyprus as a new UN member. Albania would have secured a seat at the United Nations even without Turkey’s vote, and, likewise, Albania’s first vote with Turkey against Cyprus’ UN accession in 1960 did not prevent the latter from being admitted as a UN member. But both gestures showed the countries were sympathetic to each other, even at a distance, and actually helped to start and develop some sort of relationship during the Cold War.

Two basic factors influenced the nature of Albanian-Turkish relations during that period. First, the regional geopolitical setting, in which relations among Albania, Turkey, Greece and Yugoslavia were influenced by bilateral relations, if not interdependent. In the post-Cold War environment, a fourth country, Italy, must be added to this geopolitical equation. A clear example of the impact of this regional geopolitical setting on Albania-Turkey relations is, for example, the breakdown of Albania’s relations with the Soviet Union in the 1960s. Relations with Turkey took precedence in this difficult period, and Albania began to see Turkey as a strategic ally (Xhaferi 2017,42-62) in the face of permanent dangers and threats coming from its northern and southern neighbors, respectively Yugoslavia and Greece. The influence of third countries, especially Greece, in bilateral relations between Albania and Turkey continued to be present after the end of the Cold War – and even continues today. While the real degree of this influence is very debatable, there is no doubt that there is a strong perception of its importance, up to the degree of dependence. Thus, a realistic and critical analysis of Albania-Turkey relations would not be complete without considering the influence, or perception of the influence, of Greece. As in bilateral relations between Albania and Greece, the potential influence of Turkey and up to a balancing role of Ankara with the relations between Tirana and Athens should be taken into consideration.[1]

The second factor that influenced Albanian-Turkish relations during the Cold War relates to the perceptions Tirana’s communist regime held about Turkey. Although Turkey had been a NATO member since 1952, it seemed that Tirana did not identify it as part of the “Western imperialist world,” much less as an enemy of Albania, a label reserved for the United States, and its “American imperialism,” and after 1961 also for the Soviet Union, or as the Tirana regime called it, “Soviet Social Imperialism.”

There is no doubt that such a perception has been influenced by history — the long coexistence resulting in shared cultural or religious components. However, softer language and almost neutral attitudes from communist Albania were also used with other countries in the West — members of NATO, an alliance that the regime called “a tool in the hands of American imperialism.” One significant example was the case of relations with Canada, a Western power with which the Albanian communist regime tried to establish relations, despite the fact that Canada was a purely capitalist country and, moreover, a NATO member.[2] Nonetheless, political relations throughout the Cold War between Albania and Turkey were sporadic but not insignificant, although contacts were limited. It is interesting, for example, that in 1968 the speaker of the Turkish parliament, a NATO member, visited Albania in an attempt to discuss cooperation between the two countries. During the late 1980s, the two countries intensified political communication, including visits at the ministerial level culminating in the visit of the Turkish Foreign Minister in 1988. In the meantime, there were cultural exchanges in the field of tourism. In 1982, the two countries signed a trade agreement. Two years later, an aviation agreement was signed, although flights did not start before 1986.[1] It appeared easier for Albania to open to the world starting with countries like Turkey, toward which the communist regime had not attempted to cultivate any particular hostility and had generally been shown to be neutral. Thus, when the regime in Tirana was still on its feet, although in its last throes, the communist president, Ramiz Alia, chose in 1991 to visit Turkey.

Post-Communist Albania: The Strategic Dimension of Relationships

For almost a quarter of a century after the fall of communism and Albania’s emergence from its long isolation and ideological bunker, Albanian-Turkish relations developed in a linear way, consolidating and advancing steadily. In the international relations of post-communist Albania, relations with Turkey were probably the only ones that didn’t go through ups and downs — there were no clashes, disagreements and even less any crisis — phenomena that have actually accompanied the relations with many other states, including countries with which Albania claims to have strategic relations. With the exception of the different positions regarding Turkish Cyprus, which Albania does not recognize as an independent state, there is no dispute between Albania and Turkey that could damage the relations and the climate of friendship that exists between the two peoples. The fact that Albania does not recognize Turkish Cyprus has not had any impact on relations, and Turkey has never conditioned the development of relations on the issue of recognition.[1]

For more than 25 years, Turkey has offered Albania a privileged relationship in the Balkans. Turkey was the first country to provide assistance to Albania’s devastated economy through a $13.87 million loan in 1991 when the communist government was still in power. Turkey was the first country with which Albania signed a Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation just three months after the first non-communist government came to power.[2] In three critical moments for the sovereignty and national security of Albania, in 1991, with the outbreak of wars in Yugoslavia, with the crisis of 1997 that led to the fall of the Albanian state, and in 1999 during Serbia’s aggression against Kosovo, Turkey has unreservedly supported Albania. In all three cases, the sovereignty, territorial integrity and security of the country were endangered.

Turkey was one of the first countries to recognize the independence of Kosovo and, since 2008, supports and helps the internal and external consolidation of the state of Kosovo. Consistently, Turkey has optimistically supported Albania’s membership in NATO.

From the first aid to soft loans, economic relations have grown, paving the way for investments in strategic sectors such as the banking system,[3]energy, telecommunications, education, construction and health. The revival of religious practices in Albania after a total ban under communism, Islam in particular, through the education and training of clerics, building infrastructure and religious institutions, was greatly assisted by Turkey and its relevant institutions.[4] In this solid development of relations, the strategic dimension is the basic feature. During the Cold War, Turkey had outlined a strategic and balancing role in the Balkans, especially in terms of Albania’s relations with Yugoslavia and Greece. With the dramatic developments of the late 1990s, the resurgence of national issues, the outbreak of conflict, especially the war in Kosovo and the resurgence of Greece’s aspirations in southern Albania, according to the Vorio Epirus platform, Turkey seemed to be Albania’s natural ally. In addition to the common historical past and Turkey’s own interest in expanding its influence in the Balkans, a fundamental reason why Turkey became Albania’s natural strategic ally was Turkey’s rivalry with Greece in the region.[1]

Throughout the trajectory of the development of Albanian-Turkish relations during the past three decades, one can notice the strategic character of the relations and the behavior of Turkey as a natural ally of Albania. First of all, this can be seen in the area of defense and security. In 1992, Albania and Turkey signed a special pact in the field of security and defense.[2] Emerging from communism with a bankrupt state, economy, and defense capabilities, Albania, which risked a military confrontation with Serbia, sought and supported its defense and security with special relationships with the United States, Turkey, and other NATO member states. (Biberaj, 1998).

The security and defense pact was first tested in the 1997 crisis, which accompanied the collapse of pyramid schemes and almost led to the failure of the Albanian state. The crisis of 1997, the most severe in the modern history of Albania, questioned the existence of the state and endangered the sovereignty and territorial integrity of the country. Anarchy and the loss of state control over its territory and international borders during this crisis encouraged nationalist forces and groups in the Balkans (Biberaj 2011, 312-341) and, in particular, extreme nationalist circles in Greece, which reverted to the narrative of Vorio Epirus. When a senior Greek government official visited southern Albania without announcing and coordinating with authorities in Tirana, it led to harsh words and conflict between Tirana and Athens.[3]The stern messages didn’t just come from Albania, but Turkey too. Ankara sent a clear message that it supported Albania, its sovereignty, and territorial integrity.[4] During Albania’s turbulent years in relations with Greece in 1994[5] and 1997[6] or the risk of a military confrontation with Serbia in 1999, Turkey was not really tested in terms of a possible military engagement. However, in the diplomatic field, in both cases, in 1997 and 1999, Turkey sided with Albania, sending clear messages to Belgrade and Athens. When war broke out in Kosovo, the risk of Albania’s involvement in the conflict with Milosevic’s remaining Yugoslavia was imminent, and the Albanian Prime Minister turned to Turkey for military assistance. Following Albania’s request, Turkish Prime Minister Bulent Ecevit responded that “Turkey and its Armed Forces were ready to defend the territorial integrity of Albania.”[1]

But the strategic character of Albania-Turkey relations goes beyond the new geopolitical map created by the end of the Cold War and the fall of totalitarian/authoritarian regimes in the Balkans or subsequent changes on this map. Moreover, the relations’ strategic character relates to more than just security and defense issues. The two countries’ economies and the complex economic relations between them make Turkey an important and strategic country for Albania.[2] The two countries have signed several agreements on economic cooperation and investments. And, in 2018, Albania and Turkey signed a new economic agreement, which provides for the establishment and functioning of joint committees. In 2019, Turkey was one of the four most important trading partners of Albania besides Italy, Greece, and China, with the volume of trade exchanges reaching 512 million Euros.[3] Although trade exchanges have increased, and these are quite competitive with EU member states Greece and Italy and outside the EU with China, in fact, it is Turkish investment and its ever-increasing level and above all the nature of investment that makes economic relations with Turkey strategic.

Turkey is one of the largest foreign investors in Albania, ranking third overall. Since 2014, Turkish investments have reached 419 million Euros[4]. Turkish investments include strategic sectors such as energy, banking, telecommunications, health, construction, education, and communications.

Albania’s newly-established national flag carrier, Air Albania, is also a partially Turkish investment, with Turkish Airlines owning 49.1 percent. Recently, Turkey also discussed investing in the construction of Vlora Airport, the third international airport after the one in Kukes, which started operations in the summer of 2021.[5]

Turkish investments in the field of education have also been particularly important during the post-communist transition in Albania. In a way, these investments in a chain of secondary schools saved the quality of Albanian education, which had declined after the fall of the regime. Turkish colleges in Albania became famous for their high standards, high level of teaching and enrichment of curricula at a difficult time for education in Albania. Meanwhile, several hundred Albanian students studied at Turkish universities with financial support from the Turkish government. In the first decade of the transition, Albania had a privileged relationship with security and defense schools and academies, a tradition that continues today. Last but not least, Turkey’s investment and assistance in reviving Islam in Albania after an extreme ban of almost half a century has been truly strategic. At the beginning of the Albanian transition, at least in the first decade, the tradition of Albanian Islam, a modern tradition based on tolerance and coexistence with other religions in Albania, was endangered by a kind of invasion from abroad and the importing of a more radical Islam. This contained the risk of securitization of Islam as well as a greater role of Islam in the organization of society, when historically in Albania religion has never served as an organizing ideology of society or even less of the state. The help of Turkey, the religious institutions of Turkey, for the reconstruction of the infrastructure, the education of the clergy and the reopening of the madrasas helped a lot in stopping the penetration of radical Islam. Also, the ideological revival of Albanian Islam was based on the Hanafi school, the same as the Turkish school of Islam.

“Shqiperin’ e mori turku, i vu zjarr!”[1]

In September 2020, ten years after the signing of the Albania-Greece maritime border and continental shelf agreement,[2] Dora Bakoyannis, Greece’s former foreign affairs minister who signed the agreement in 2009 as her country’s representative in Tirana, said that Albania had ultimately voided the deal in 2010 under Turkey’s influence. According to her, the decision of the Albanian Constitutional Court to declare the agreement invalid was not a sovereign decision of Albania but an intervention of third parties, namely Turkey.[3]

The accusation that Albania’s foreign policy in the Balkans, especially in dealings with Greece, is dictated by Ankara is a constant and consistent topic in the Greek press. Even though such a perception had existed since the beginning of the opening of Albania after the fall of communism, during the last decade, and especially after 2013, when the Socialists led by Edi Rama came to power, it is ever more present.

However, the perception that Ankara, if not in direct control of Tirana’s foreign policy, at least substantially influences it, doesn’t just relate to Albania’s foreign policy toward Greece. According to Romano Prodi, the former Italian prime minister, Turkey is advancing in Albania by increasing its area of influence at the expense of Italy.

… There is some positive data on cooperation between Italy and Albania. However, it is getting harder every day to strengthen them or just renew them. The curriculum of our language suffers from limited resources, while [Italian public broadcaster] Rai’s presence has become marginal and given way to Turkey, which is becoming increasingly active with broadcasts in Turkish, translated into Albanian. Although not yet with the same intensity as in other Balkan countries, the Turkish presence is growing in all areas, from public works to culture, from the military sector to an ever deeper penetration into the religious field, through support for a widespread network of mosques. The presence is strengthened by the friendly relationship between Turkish President Erdogan and Albanian Prime Minister Rama, who is increasingly attentive to the political choices of his colleague…[4] Last but not least, the nature of the current relations of Albania with Turkey has raised questions about Albania’s foreign policy toward the European Union. There is a view that such close ties between Albania and Turkey could undermine Albania’s aspirations for membership in the European Union.[1] In some EU institutions, there have even been rumors that Turkey is using Albania as a base for its expansion toward Europe.[2]

There are three basic views that are becoming ever more present in the discussion about the nature of Albania-Turkey relations in the period that started with the coming to power of Edi Rama’s Socialists in 2013. First, there is the view that Albania is increasingly losing its independence in foreign affairs in favor of Turkey. Second, Albania is gradually sinking into the orbit of Turkey, which is taking Albania away from Europe. Third, Turkey is expanding its influence in Albania at the expense of other countries, with Albania even serving as a Turkish base for expansion toward Europe.

All these three points of view prevalent in the current debate are interrelated, and they project a vassal relationship. Or, to quote the verses of Çajupi, a prominent poet of the Albanian National Renaissance: Albania has been taken by the Turks. Those verses inspired Albanians in the early 20th century to liberate themselves from the Ottoman Empire.

Of course, the three points of view mentioned above project a reactionary Turkey, one working against Europe, a Turkey that is against the integration of Albania or other Western Balkan countries into the European Union and as such contain risks. But is it true — that — in the words of Çajupi — Albania was taken by the Turks and set on fire? Is there really any evidence that would suggest substantial changes in the nature of interstate relations and, in particular, what evidence is there for the thesis that Albania is losing its independence in foreign affairs in favor of Ankara?

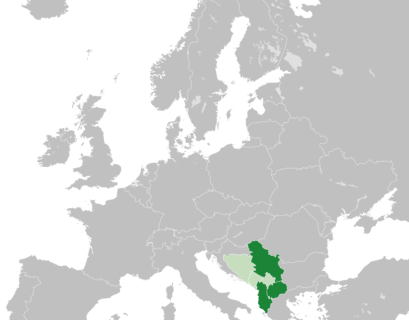

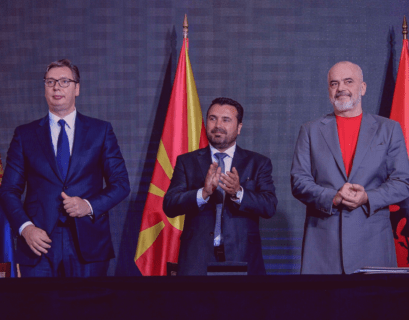

What many observers agree on is that there is currently a new approach to developing relations with Turkey, a change in form rather than in content: from the traditional institutional approach to a new approach based on the personal relations between the two leaders (Madhi 2021, Lami 2020, Krisafi 2021). But Albania-Turkey bilateral relations are not alone in operating in the eight years based on personal relations between the leaders. Relations between Turkish President Erdoğan and Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić resemble those between Mr. Erdoğan and Mr. Rama and vice versa. And the same approach can be seen in the interstate relations between Turkey and other countries in the Western Balkans.

The issue of sovereignty and independence in foreign affairs, both theoretically and practically, is more complex in the case of small states, especially in the case of small states that are also weak states, which is the case with Albania. Small and weak states in the international political arena have their behaviors conditioned by, among other things, the nature of the international environment. During the Cold War, Albania applied asymmetric relations with the Great Powers as a way of survival, and in any case, when it chose independence in foreign affairs the result was isolation. But, in the post-Cold War environment, independence in foreign affairs, especially for small and weak states, is limited. Albania is no exception to that rule. Although there is episodic evidence that shows it conducting a foreign policy reminiscent of client state behavior, Albania is currently a NATO member, and it seems paradoxical to believe that it can “hand over its independence” in foreign affairs in favor of another country, which also happens to be a member of the alliance, albeit a much larger state and a Middle Power like Turkey. If there is one country that has had more influence than the rest over the past 30 years in Albania’s foreign policy, it is the United States.[3] According to the annual studies conducted by the Albanian Institute for International Studies, several other countries — Italy, Germany, and even Greece — but not Turkey — have had an impact on Albania’s policies, including in the foreign policy realm.

The thesis of handing over the driving seat in foreign policy to Ankara is not the case even in the Albania-Turkey-Greece triangle, where Turkey has always played the balancing role. The majority of Albanian citizens believe that relations with Greece are important and that the government should pay special attention to the development of these relations.[1] The example that former Greek Foreign Minister Bakoyannis brought to argue the influence of Turkey on Albania’s policy toward Greece shows how baseless and unrealistic the argument she made is — even as a perception. In 2010, when the Albanian Constitutional Court voided the agreement on the delimitation of the maritime border and continental shelf between Albania and Greece, the Socialist Party and Edi Rama were in opposition, which excludes the influence the former Greek foreign minister proposes.[2]

But the thesis of handing over independence in foreign affairs is not supported even by a simple analysis of Albania’s behavior and actions during the last ten years, which, in fact, coincide with major achievements of Albania’s foreign policy: NATO membership in 2009 and obtaining the status of EU candidate country in 2013.

Regardless of the nuances reflecting changes in different Albanian administrations, Albania has generally supported the policies of the West in the Balkans — those of the United States, European Union and NATO. And Turkey’s foreign policy in the Balkans has not been substantially different, much less the opposite of that of Western countries when it comes to fundamental issues such as peace and security, including the European future of the Balkans.

Ahmet Davutoğlu’s 2009 reference to the “golden era” of the Ottoman Empire in the Balkans started many debates, with some even warning of the “risk” of Turkish Neo-Ottomanism in the Balkans, including Albania[3].

But for more than a decade, it has been proven that there is no qualitative change or deviation from the policy that Turkey pursued in the Balkans the first two decades after the beginning of the disintegration of Yugoslavia. Turkey has not made and does not make any changes to its development of relations with the Balkan countries. It has joined peace-building efforts and supports efforts to resolve the frozen Serbia-Kosovo conflict. Turkey has supported Kosovo’s independence as the second country to recognize its independence but currently also has excellent relations with Serbia. This policy is quite similar to that of the leading Western countries, which supported NATO’s engagement against Slobodan Milošević’s Serbia and then Kosovo’s independence. At the same time, the Italian worries that Turkey is advancing in Albania at the expense of Italy[4] prove unfounded when we compare Albania’s relations with Italy and Turkey in the political, economic and cultural fields. Italy has been and remains one of the most strategic and important partners for Albania, and the development of relations with Turkey cannot compete with an ally like Italy.[5] On the economic front, Italy has been and continues to be the top partner for Albania. In the cultural arena, Italy does not have the supremacy that it had in the early 1990s. RAI and other Italian channels, which were often the only window Albanians had to the West, have of course lost some ground, but that ground has not been lost to the so-called “aggression of Turkish television shows,”[1] which in reality have a minor and peripheral influence on Albanians.[2]

European Suzerainty vs. Turkish Suzerainty

For more than two decades after the fall of communism, interstate relations with Turkey were an important component of Albanian diplomacy’s efforts to lift the country out of isolation and link it to the West. Neither the Albanian government nor the Albanian society at large,[3] had any dilemma during that period that growing good relations with Turkey would not be helpful with Albania’s integration into the Western world, much less of a dilemma that cooperation with Turkey could damage Albania’s Western aspirations.

On the other hand, in its politics and engagement in the Balkans, Turkey has seen itself as a member of the Western alliance[4] not simply because of its NATO membership but also because of its traditional Western identity (Demirtas, Birgul 2013). Over the past ten years, Turkey’s foreign policy, in the Balkans, including Albania, and beyond, has been influenced by Davutoğlu’s “Strategic Depth” doctrine, which essentially aims at multidimensional diplomacy, claiming to play a greater role in global politics. Although he called for an increased role for Turkey in the Balkans, referring to the “golden era” of the Balkans under Ottoman rule, Davutoğlu did not aim for his country’s diplomatic engagement to restore this “golden age” against the aspirations of Balkan societies to integrate into the European Union.

Despite the thesis that, under the new ideology of Ottomanism, Turkey intends to control the Balkans, Ankara has supported the idea that the region will have peace and security united under the same roof, and now that roof – according to former Turkish President Abdullah Gül – is the European Union umbrella.[5] The changes of the last five or six years and the accommodation of Turkey’s foreign policy in the Balkans are not related to any substantial changes that oppose the European future of the Balkans. Turkey’s new strategy in the Western Balkans is a pragmatic approach with a very central role of President Erdoğan through personal connections with the respective leaders of each state.[6]

But despite all this, there is a growing perception that Turkey is increasing its influence in the Balkans at the expense of Brussels.[7] And Albania is seen as one of the most vulnerable links, a country that could end up in Turkish orbit, forced to choose between Turkey and the European Union. In fact, three theses are being discussed in the current debate about Turkey’s role and ambitions in the Balkans. The first refers to the return of geopolitics to a new context where third powers outside the Balkans are in a strong competition to influence and control the Balkans, including Turkey – along with Russia, and further afield, China and the Gulf countries.

The second thesis, which is tied to the first, postulates that Balkan countries, frustrated by the slowness, powerlessness and lack of will of the European Union, are increasingly turning their attention to other powers — and in the case of Albania, in the most plausible scenario, that alternate is Turkey.

The third thesis refers to the nature of regimes in the Balkan countries. According to this third point of view, the regimes in the Western Balkans are increasingly resembling more and more autocratic political models seen today not only in Russia but also in present-day Turkey. The ultimate irony is that in the Balkans political elites are building regimes that increasingly resemble Kremlin Inc. – all this while ringing alarm bells on the threat of Russian imperialism in the Balkans to scare the rest of Europe in order to take in the region.[1]

While the first thesis is not valid in the case of Turkey, which has shown that it supports the “European Suzerainty” of the region, the second thesis is in itself baseless. European integration is not a foreign policy issue. The case of Albania is quite significant. Support for European integration in Albania is total, with more than 90 percent of Albanians that would support integration in the event of a referendum. In Albania, there is no influential political party or individual that advocates against integration, and recently Albania has consistently supported the European Union’s foreign policy. However, progress on the path to EU integration has been very slow, with Albania standing still in its status quo for at least five years. The European Commission has proposed to the European Council the opening of Albania’s EU accession talks three times in a row, only to have the decision postponed. A look at the recommendations EU institutions or member states make to Albania, (for example the German parliament), shows that the conditioning of opening membership negotiations relates to the functioning of the state, rule of law, democratic standards, legitimacy of institutions as well as the necessity of organizing free electoral processes, the fight against corruption and organized crime.[2] There is no mention of the foreign policy, orientation, or strengthening/weakening political or economic relations with Turkey.

In many cases, this thesis has been used by political leaders in the Western Balkans to urge the speeding up of the accession process, based on the logic that if the EU does not accept Albania or the rest of the Western Balkans, then Russia or other competing powers will move in to replace the EU. The argument and the meaningless hope in this case is to blackmail the EU and/or EU member states.[3]

The vein of concern about a sort of vassal relationship between Tirana and Ankara and the idea that, between Turkey and the European Union, Albania is choosing Turkey are two issues that largely started to come up for discussion after the failed coup attempt in Turkey in 2016. The first event that led to strong debate was in the summer of 2019 in Tirana, when the local authorities allowed the erection of a monument commemorating the victims of the failed coup in Turkey. The erection of the monument in Tirana seemed like an attempt to give legitimacy to the policies and actions the government took after the coup was suppressed. The establishment of the memorial in Albania was seen by many as wrong, among other things, because the decision-making process was not transparent. According to critics, if Turkey wants to erect a memorial for its citizens, let it do so in Marmaris or somewhere else in Turkey, where it would make a lot of sense. The establishment of a memorial in Tirana violates Albania’s sovereignty. The critics, mostly independent experts in international relations, questioned whether Albania had become a colony of Turkey or whether Turkey controlled Albania’s politics and economy.[1]

The second event was the deportation of the first “Gülenist” from Albania to Turkey. The Balkans became kind of a proxy territory in the conflict between President Erdoğan and members of the movement led by cleric Fethullah Gülen. The movement is accused of being the force behind the failed coup attempt in 2016. The Balkans became in fact the exclusive region where the attention and actions of the Turkish authorities, mainly the intelligence services, were concentrated, which in cooperation with the governments of the Balkan states began searching for and extraditing members of the Gülen movement. In 2018, the Turkish intelligence services in cooperation with the Kosovo intelligence service — in the words of the UN Human Rights Council report — “effectively kidnapped” six teachers, accused of being members of the Gülen movement. In January 2020, Turkey hailed the deportation of the first Gülenist from Albania as another MIT intelligence operation.[2] The Albanian authorities denied that the forcible return of the “Gülenist” Harun Çelik was the result of close relations between President Erdoğan and Prime Minister Rama. “This is a matter of legal procedures, not related to the Prime Minister’s Office,” the spokesman of the Prime Minister of Albania told the media.[3] The case of Harun Çelik is so far the only one from a relatively considerable number of Turkish teachers who, until 2016, worked in the network of Turkish colleges in Albania, distinguished for high standards and performance, but who after the coup were identified as part of the Gülen movement.

From the legal standpoint, the “handover” of Mr. Çelik to the Turkish authorities by the Albanian authorities seems like a normal action and a formal procedure. The legal reason for the “handover” was related to the fact that Mr. Çelik had used forged travel documents. This seemed to provide a good opportunity for the Albanian government to satisfy Ankara’s insistence and, at the same time, justify the handover of the “Gülenist” based on a legal procedure. That case might have helped get rid of other “Gülenists” from Albanian territory. It is likely that many others were also encouraged into “voluntary departure” after being identified as members or supporters of the cleric Fethullah Gülen.[4]

Although both of these developments are questionable, they are not enough to arrive at the conclusion that Albania has lost its sovereignty or that it is becoming a Turkish colony. However, both of these developments cast deep doubt on the democratic credentials of the political system and government in Albania, including law enforcement and the rule of law, which are fundamental and non-negotiable for European integration.

A “kurban” to the Sultan?[5]

On May 28, 2013, the chairman of the Socialist Party of Albania, Edi Rama, was traveling on a Turkish Airlines flight to Ankara. A journalist who communicated with one of the aides of the VIP passenger was given the hint that the then leader of the Albanian opposition was going to a meeting with the “Sultan.” Immediately after the meeting, Edi Rama stated that “with rare hospitality” during the “unforgettable meeting” they had discussed with Prime Minister Erdoğan on “the fight against corruption and unemployment, stopping the devastation in education and health, the economic and social renaissance, [Erdoğan’s] achievements today and ours tomorrow”.[1] The meeting was only three weeks before the June 23 parliamentary elections in Albania, which would bring Edi Rama’s Socialists to power. There is an unwritten rule that is generally followed prudently by the governments of other countries in the case of political elections. During the election period, high-level visits of the government and especially the opposition of a friendly country are avoided in order to maintain neutrality toward the parties in the race.[2]

Turkey and Prime Minister Erdoğan chose not to adhere to this unwritten rule that is typically consistently followed. The candidate for Prime Minister of Albania was received with great honors by the Prime Minister of Turkey, who wished him success at the peak of the electoral campaign in Albania. Both the host and the guest exchanged gifts, books, to be precise. According to the Albanian press reporting on the meeting, Mr. Rama gave a gift — his book “Kurbani,” whose title is a Turkish word widely used in Albania to signify a sacrificial lamb to God or a person made to pay the price for a cause. But it was a lapse in reporting, as it was the other way around: then Prime Minister Erdoğan gave his book to Rama. But that misreport added fuel to voices critical of Turkey’s policies, labeling Mr. Rama’s visit to Ankara as “The Sacrifice to the Sultan”. That first meeting would pave the way for an ever closer relationship between the Prime Minister of Albania Rama and the Prime Minister/President of Turkey Erdoğan.[3]

The past eight years have seen an intensification of Albania-Turkey relations. In addition to trade exchanges, investments have increased or maintained a steady trend. More than 600 Turkish companies currently operate in Albania and if service contracts are included, Turkish investments reach the figure of USD 3.5 billion.[4] Turkey was one of the first countries to come to the aid of Albania after the earthquake of November 2019 and one of the major contributors to the alleviation of the consequences of the earthquake.[5]

In January 2021, Turkey and Albania signed a political declaration for the establishment of the High-Level Strategic Cooperation Council,[6] a new mechanism proposed by Ankara to strengthen and enhance bilateral cooperation in the Balkans.

This was the second proposal on the establishment of the council, but the body is not yet operational. Initially, this instrument was proposed to Serbia in 2018 and gave a new impetus to the development of its relations with Turkey.[7] In January 2021, President Erdoğan stated that Turkey’s relations with Albania were raised to the level of strategic partnership.[8]

However, despite the insistence of both Turkey and Albania to label relations as a strategic partnership – which is, based on the statements of January 2021, seen as a major achievement and qualitative change in interstate relations – in fact, the relations between Albania and Turkey have been strategic since their inception in 1992. There are two reasons for that conclusion. The first reason is geopolitical and concerns Albania’s relations with Greece but also Serbia. In a broader geopolitical context, the equation according to which Serbia develops strategic relations with Russia and Albania develops strategic relations with Turkey – a narrative that is part of more than just conspiratorial circles in the Balkan capitals, starting with Belgrade – does not correspond to reality.[1] In that geopolitical aspect, Albania does not balance the Serbia-Russia axis with Turkey, but with the United States and NATO, and Turkey is also a member of the latter.

Second, in the economic field, the relations were and are strategic because Turkish investments have always been in the most strategic sectors. Since 2013, Turkish investments in Albania have not seen any substantial changes. After almost a decade of the increasingly close personal relationship between Mr. Rama and Mr. Erdoğan, critical voices have become louder in noting that Rama has become a victim of the “Sultan” in the sense that Albania is increasingly dependent on Turkey.

If the risk of “Turkish Suzerainty” against “European Suzerainty” over Albania is a perception that does not seem to coincide with reality, another factor has changed, and it has the potential to damage interstate relations. For the first time in the past 30 years, Turkey no longer seems to be neutral in Tirana’s political power competition. What has changed is not in fact the strategic character of the relations but the spectacular support that President Erdoğan has shown for Prime Minister Rama in the game of power within Albania. Some of the recent Turkish investments in Albania, such as the establishment of a regional hospital in central Albania, which Erdoğan himself said would be completed before the elections,[2] and the construction of more than 500 homes by Turkey at the height of the election campaign as part of earthquake aid were spectacular in their support of the governing party on the eve of the 2021 elections in Albania.

Historically, Ankara has been careful not to support one political party more than others in Albania. Turkey’s focus has not been on whether Albania is ruled by the Socialists or the Democrats, the two main political groupings that have exchanged in power in Albania since 1992. It showed no hesitation in 1991 to have a fresh start in relations with Albania even though the head of state was still Ramiz Alia, the country’s last communist leader and direct successor of the dictator Enver Hoxha. Such political behavior by Turkey has had a positive impact on the leaders of Albania. In 1997, the ruling Democrats assumed that Turkey would definitely support the Democratic Party government and President Sali Berisha in the conflict with the Socialist opposition. This is also due to the fact that the Socialist opposition demonstrated a kind of preference for cooperation with Greece over Turkey.[3] However, Ankara was determined to be neutral in the political competition among political parties or individuals in Albania and determined not to support one government over another but rather the Albanian state. When the Socialists came to power after the 1997 elections, Ankara showed the same readiness and offered Prime Minister Fatos Nano an excellent cooperation relationship. Last but not least, there is a perception that religion is being used as a political instrument in contemporary Turkey-Albania relations. According to the critics, Turkey is using religion as a political tool, it is politicizing religion, and this politicization in Albania could have catastrophic consequences.[1] This would mark a significant change in Turkey’s foreign policy toward Albania. It’s the first time that the discussion on relations between Albania and Turkey deals with concerns on the use of religion as a political factor. As noted, the resurgence of religious belief, Islam in Albania, the construction of infrastructure and the training of clerics were greatly assisted by Turkey in the first two decades of transition. However, Turkey’s help during that period was in a way neutral and stripped of political interests. It helped revive traditional Albanian Islam, which, although similar to Turkish Islam and the Turkish practice of Islam, had managed to develop an identity of its own until the communists came to power after the Second World War, first limiting and then outright banning all religious practices – making Albania the first atheist country in the world.

Furthermore, the assistance provided by Turkey in the revival and reconstruction of religious institutions and infrastructure in Albania was not used by Ankara to advance its political interests. But, currently, there is a perception that Turkey is investing in the construction of new mosques[2] to create an Ottoman virtual space in Albania. Three years ago, Turkey financed the construction of the largest mosque in Albania — with a fund of 60 million Euros.[3] The Turkish investment in the construction of mosques seems to be a strategic interest and does not only include Albania.[4] The construction of the mosques is linked to President Erdoğan’s efforts to advance Islam with the aim of leaving a legacy both at home and abroad as a man who has advanced the interests of Muslims around the world.[5] But religion, including Islam, is certainly peripheral to Albanians, and, moreover, religion has never defined Albanian identity.

Back to the Future –In Lieu of Conclusions

Modern Albania-Turkey relations have developed in a linear way since the fall of communism in 1991 when Albania started to open up to the world. There are no disagreements between the two countries. Cooperation is strong in all areas, with security and defense as well as economic cooperation standing out. That has created a solid relationship without any ups and downs. Turkey is a strategically important country for Albania. In the current geopolitical setting in the Balkans and in the national security equation of Albania, Turkey has had and continues to have a balancing role. The nature of Turkey’s investments in Albania — in the most important sectors of the economy — also makes relations with Turkey strategic.

Regardless of the shared Ottoman legacy and religious ties, there are cultural boundaries between Albanians and Turks, the observance of which occurs naturally. Crossing or attempting to blur these cultural boundaries may carry risks.

The development and deepening of relations with Turkey, a NATO member country and an EU aspirant, cannot prevent Albania from joining the European Union. Turkey’s use of religion as a political instrument to advance and deepen relations and increase its influence in Albania is unhelpful and may have the opposite effect. For Albania, a country where religion has never served as an organizing ideology for society and even less for the state, this would have serious implications for national security and its European future. The transformation of Albania into a proxy territory where an internal conflict of Turkey is exported does not fit well with the consolidated tradition of relations. The episodes in which Albania has been such a proxy reveal Albania’s weak democratic credentials and may damage Albania’s European prospects. Moreover, these proxy episodes simultaneously create the image and perception of Tirana’s dependence on Ankara. The close personal relations between the political leaders which are not at all a novelty in the international relations cannot damage the Albanian-Turkish relations as long as these personal relations translate into an institutional cooperation that coincides with the best tradition of modern relations seen after the end of the Cold War.

Ankara’s moving away from a clear neutrality approach in Tirana’s internal political power plays could undermine the future of interstate relations while a return to a neutral approach is a guarantee for a better future.

Footnotes:

[1]Northern Epirus is an essential part of the Greek nationalist platform Megali Idea or Greater Greece, as a political territorial claim of parts of today’s southern Albania.

[2] See Krisafi, Ledion, Albania between Turkey and Greece, Tirana Observatory, Winter 2021, Vol 3 NO 1, p 16. Also see Lami, Blendi, Albania in the Turkish Greek Conflict, Tirana Observatory Fall 2020, Vol 2 NO.4 p 322- 326.

[3]See Triadafilopulos, Triadafilos. A Reluctant Gesture: The Establishment of Canadian- Albanian Diplomatic Relations, at Rakipi, Albert (ed) Albania in International Relations, Albanian Institute for International Studies, (AIIS ) p 254- 270 Tirana, 2013.

[4]Tzounis, L. Albania in 1985, Tirana Observatory, Foreign Policy and International Relations , Vol1 No.1 Albanian Institute for International Studies (AIIS), Tirana 2019, p.37-41

[5] Interview with R. A., former senior diplomat of the Albanian government (1992- 1997)

[6] Treaty of Friendship and Cooperation signed on June 1, 1992.

[7] Turkish-owned National Commercial Bank, BKT, is the first foreign commercial bank in post-communist t Albania.

[8] See Rakipi, Albert. Tranzicionii Islamit Shqiptar- Ringjallja e njeprojekti liberal (in Albanian) Transition of Albanian Islam, Revival of a Liberal Project, Interreligious Institute, Tirana 2020

[9] See Gangloff, Sylvie. The Politics of Turkey. Quoted at Ledion Krisafi, Albania-Turkey relations: In the Shadow of History, AIIS 2020.

[10] Agreement in the field of Defense and Security 1 July, Ankara. In 1998, Albania and Turkey signed another agreement in the field of security and defense, according to which Turkey undertook the reconstruction of the naval military base in Pasha Liman and the Naval Academy in Vlora. Since 1995, the two countries have been organizing joint military exercises.

[11]The Albanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs called the Greek Ambassador to Tirana to seek an explanation for the unauthorized visit of the Greek Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs to southern Albania but also to convey the disappointment and frustration of the Albanian diplomatic authorities. Interview with a former high official of the Albanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, August 2021.

[12] Statement of the Minister of Foreign Affairs of Turkey was made public after the visit of a high-ranking Albanian diplomat in Ankara whose purpose of travel was consultations with the Turkish government and delivery of a message that the President of Albania Sali Berisha sent to the President of Turkey Demirel. See “TURKEY WILL NOT STAY SPECTATOR TOWARDS EFFORTS TO DIVIDE ALBANIA” – declares Tansu Ciller –“ Albanian Telegraphic Agency ( ATA) March 21, 1997, at http://www.hri.org/neës/balkans/ata/1997/97-03-21.ata.html

[13]See Biberaj, Eleza. Albania in Transition , The Rocky Road to Democracy, AIIS,2011

[14] Calls for autonomy of Northern Epirus and partition of Albania.

[15] Quoted by Ledion Krisafi, Leonard Veizi.

[16] According to several AIIS polls, Albanian citizens feel that in considering Turkey as a strategic country for Albania, economic issues should also be taken into account.

[17] See Krisafi, Ledion. Economic Relations Albania and Turkey: In the shadow of History. AIIS, 2020

[18] Ibid

[19] Ibid

[20] The words mean “Albania has been taken by the Turks … set on fire.” The verse is the beginning of a poem titled “The Albanian” by Andon Zako Çajupi (27 March 1866 – 11 July 1930). The poem in question has been identified as an anthem for freedom and the liberation of Albanians from the Ottoman Empire. Çajupi was a prominent activist of the Albanian National Renaissance and one of the most prominent poets of that period.

[21] The agreement between Greece and Albania on the delimitation of the continental shelf and other maritime areas between Albania and Greece was signed in Tirana on April 27, 2009, during a visit of the Greek Prime Minister Karamanlis. The Socialist Party, at the time in opposition, led by Edi Rama, challenged the legitimacy of this agreement in the Constitutional Court, which voided the agreement a year later.

[22] See The Economist Conference: The Balkans beyond 2020, at https: //euroneës.al/al/vendi/2020/09/16/perplasje-per-detin-rama-e-bakoyannis-replika-per-nderhyrjen-turke-ne -vitin-2009/

[23] See Prodi, Romano: Il Caso Albania / I rapportinelMediterraneocheservano al Meridione. Il Messaggero. Aug. 15, 2020 https://www.ilmessaggero.it/editoriali/primopiano/romano_prodi_il_caso_albania_i_rapporti_nel_mediterraneo_che_servono_al_meridione-5405655.html

[24] See Hoxha, Erlis. Albania under the influence of non-Western powers. Turkey’s neo-Ottoman foreign policy agenda; at https: //www.eupolicyhub.eu/perspektiva-europiane-e-shqiperise-nen-trysnine-e-vendeve-jo-perendimore/ Dec. 3,2020.

[25]Exit. al. MEPs Raise Concerns Over Turkish Influence in Albania[1] See Albania ten years after: People on state and Democracy, Albanian Institute for International Studies, Tirana, 2020. Also see Albania and EU Perceptions and Realities, 2005-2015, AIIS, 2015

[26] See Albania ten years after: People on state and Democracy, Albanian Institute for International Studies, Tirana, 2020. Also see Albania and EU Perceptions and Realities, 2005-2015, AIIS, 2015

[27] See Albania-Greece relations: Shaping the future outlook, AIIS forthcoming publication, fall 2021.

[28] The Constitutional Court of Albania overturned the agreement in 2010, when the government of the Democratic Party headed by Sali Berisha was in power. The Socialist Party and Edi Rama, who demanded that the agreement be declared invalid, had no contact with the Turkish government of the time, much less with former Prime Minister Erdogan. See The Economist Conference, Athens, 2020.

[29] See Misha, Piro. Neotomanizmi dhe Shqiperia (in Albanian ) Zemra Shqiptare , 21.02.2010, at http://www.zemrashqiptare.net/news/13170/pirro-misha-neo-otomanizmi-dhe-shqiperia.html?skeyword=a

[30] For a more elaborate account of this idea see Romano Prodi’s book.

[31] Interview with a former high official of the Albanian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. August 2021.

[32] Interview with Ledion Krisafi, Senior Research Fellow AIIS, Director of Tirana Center for Journalistic Excellence. www.TCJE.org

[33] See Balaban, Adem. The Impact of Turkish TV Serials Broadcasted in Albania on Albanian and Turkish Relations, European Journal of Social Science Education and Research, September -December 2015 Volume 2, Issue 4

[34] Turkey was constantly perceived by the Albanian public as a place that is important to Albania and with which the government should develop strategic relations. See AIIS annual studies on the European perspective for Albania, 2003-2016.

[35] See Aydıntaşbaş, Asli, From Myth to Reality: How to Understand Turkey’s Role in the Western Balkans. European Council on Foreign Relations

[36] Statement of former Turkish President Abdullah Gül, as quoted by Asli.

[37] Ibid , Asli.

[38] See Wiesse, Zia. Turkey’s Balkan comeback, Politico. EU, May 15, 2018 at https: //www.politico.eu/article/turkey-western-balkans-comeback-european-union-recep-tayyip-erdogan/

[39] See Rakipi, Albert. European Integration: In search for the enemy, Tirana Times, June 23, 2019.

[40] See Ruttershof, Tobbias. The opening of Accession Negotiations: A new Hope for Albania, Tirana Observatory, Foreign Policy & International Relations, Vol.2 No.2 Spring 2020, Tirana 2020.

[41]Rakipi, Albert. Albania’s European Union Integration, In search of an enemy, Tirana Times www.tiranatimes.com

[42] See Philips, David. Call for Transparency for the Turkish Memorial in Tirana, Voice of America, Interview. Aug. 13, 2019. https://www.zeriamerikes.com/a/phillips-turkish-memorial/5040532.html

[43] See Buyuk, Hamdi Firat & Erebara, Gjergj. Turkey Hails Gulenist Deportation from Albania as MIT Success BIRN, Jan. 3, 2020 https://balkaninsight.com/2020/01/03/turkey-hails-gulenist-deportation-from-albania-as-mit-success/

[44]Hopkins, Valerie & Pitel, Laura. Erdogan’s great game: Turkish intrigue in the Balkans. Financial Times, January 14, 2021. https://www.ft.com/content/d99f7b3d-5dcc-4894-a455-1af5a433175f

[45] Interview with Lutfi Dervishi, Senior Journalist, Director of TV show Program Public TV, Tirana

[46] A sacrificial lamb offered to the Sultan.

[47]Shqip newspaper, Edi Rama meets with Prime Minister Erdogan. 30 May 2013. https://www.gazeta-shqip.com///2013/05/30/edi-rama-takon-kryeministrin-erdogan/

[48]Italy seems to be an excellent example of maintaining balance, neutrality to the domestic political game in Albania. No Italian Foreign Minister has ever visited Albania without meeting both the government and the opposition leaders.

[49] For a more detailed account see Madhi, Gentiola. Our brother Erdogan- From official to personal relations of political leaders of Albania and Kosovo with Turkish President Prague Security Institute, February 2021, Prague

[50] See “We plan to increase our investment in infrastructure and tourism in Albania, Presidency of the Republic of Turkey at https://www.tccb.gov.tr/en/news/542/123478/-w-plan-to-increase-our-investments-in-infrastructure-and-tourism-in-albania-

[51] Turkey is contributing with the construction of 525 houses for earthquake victims.

[52]Bir, Burak&Aydogan, Merve.Turkey Albania upgrade ties to strategic partnership Anadolu Agency Jan. 6 2021. https: //www.aa.com.tr/en/politics/turkey-albania-upgrade-ties-to-strategic-partnership/2100611

[53] Western Balkans Playbook

[54] Statement by President Erdogan during the meeting with the Prime Minister of Albania Rama, Ibid

[1] Interview with Remzi Lani.

[55] See Exit. al. Erdogan Promises to Build a Hospital in Albania before April Elections Jan. 6, 2021, at https://exit.al/en/2021/01/06/erdogan-promises-to-build-a-hospital-in-albania-before-april-elections/

[57] Interview with an Albanian former senior diplomat. August 2021.

[60] See Piro Misha, researcher, interview at Kapital TV show on Vizion Plus. Interview can be found here: “What’s the business of the Turkish president in building mosques in Albania” at https://lexo-shqip.net/archives/103392/studiuesi-Piro-Misha-cpune-ka-presidenti-i-turqise -te-ndertoje-xhami-ne-shqiperi /

[61] See Turkey starts restoration of Islamic heritage works in Albania at www.tiranatimes.com

[62] See Grand mosque given green light to start construction at Tirana Times at www.tiranatimes.com

[63]Panorama.com.al, Turkey is building 18 large mosques around the world, including one in Tirana, March 1, 2015. http://www.panorama.com.al/turqia-po-nderton-18-xhami-te-medha-ne-mbare-globin -include-one-in-tirana

[64] Ibid. In fact, the newspaper is referring to Aslı Aydıntaşbaş, a political analyst at the Turkish newspaper Milliyet.

Bibliography

Aydıntaşbaş, Asli. From Myth to Reality: How to understand Turkey’s Role in the Western Balkans. European Council on Foreign Relations

Biberaj Elez, In Transition, The rocky road to democracy, AIIS, 2011

Financial Times, Erdogan’s great game: Turkish intrigue in the Balkans String of extractions of Turkish citizens from countries beholden to Ankara is raising alarm,

Fischer, Bernd. King Zog and the struggle for Stability in Albania, AIIS Tirana, 2012

Gangloff, Sylvie. La politique dela Turquie dans les Balkans depuis 1990. Université Panthéon-Sorbonne-Paris. 2000.

Krisafi, Ledion, Albania Turkish Relations: in the Shadow of History, at Tirana Observatory, International Relations and Foreign Policy, Winter 2021, Vol 3 NO 1. AIIS, Tirana 2021.

Lami, Blendi. Albania in the Turkish Greek Conflict, Tirana Observatory, International Relations and Foreign Policy, AIIS Fall 2020, Vol 2 NO.4

Misha, Piro. Neo-Ottomanism and Albania (in Albanian), http://www. peshkupauje.com/2010/02/neootomanizmi-dhe-shqiperia, accessed March 2, 2018; 27. 28.

Prodi, Romano. Strana Vita, la mia, Solferino, September 2021

Rakipi, Albert ed, Shqipërianë Marrdheniet Ndërkombëtare (Albania in International Relations) Albanian Institute for International Studies, Tirana 2012,

Rakipi, Albert ed, Albania and Greece Understanding and Explaining Albanian Institute for International Studies, AIIS Tirana, 2018

Rakipi, Albert. Radicalization in Albania, Searching for ideological and structural roots, AIIS, Tirana 2019.

Xhaferi, Përparim. The Post Ottoman Era: A fresh start for bilateral relations between Albania and Turkey, Journal of European Studies, 2017. Vol 9 (1)

Interviews

Interview with Remzi Lani, Director Albanian Media Institute August 2021

Interview with Ledion Krisafi, Senior Research Fellow AIIS, Director of the Tirana Center for Journalistic Excellence, August 2021

Interview with Lutfi Dervishi, Senior Journalist, Director of Program Public TV, August 2021