BLEDAR FETA

International Relations Analyst

Research Associate, South East Europe Programme

Hellenic Foundation for European and Foreign Policy (ELIAMEP)

If Greece has returned to normality with the victory of the center-right New Democracy (ND) of Kyriakos Mitsotakis that held power before the far-left SYRIZA of Alexis Tsipras, the new normality could in some ways be a lot like the old one.

The main question is whether the newly elected government will keep up the current momentum of change in Greece’s foreign policy in the Balkans or it will reverted to old-fashioned geopolitics where Athens was more part of the Balkan problem rather than part of its solution.

For a long time, Greece’s foreign policy in the Balkans remained at the back burner of Greek politics, reflecting country’s economic agonies. At the same time it has been hostage to the populist version of Greek nationalism. As a result, no real progress was achieved in any of the longstanding bilateral disputes that Greece has with its northern neighbors.

This stagnation is not only due to Greece’s preoccupation with domestic economic governance issues which in some way have diverted the political will. But it is also the result of political calculations. Country’s leading political parties have been reluctant to take the political risk of addressing issues of national interest.

Greece’s foreign policy shift in the Balkans

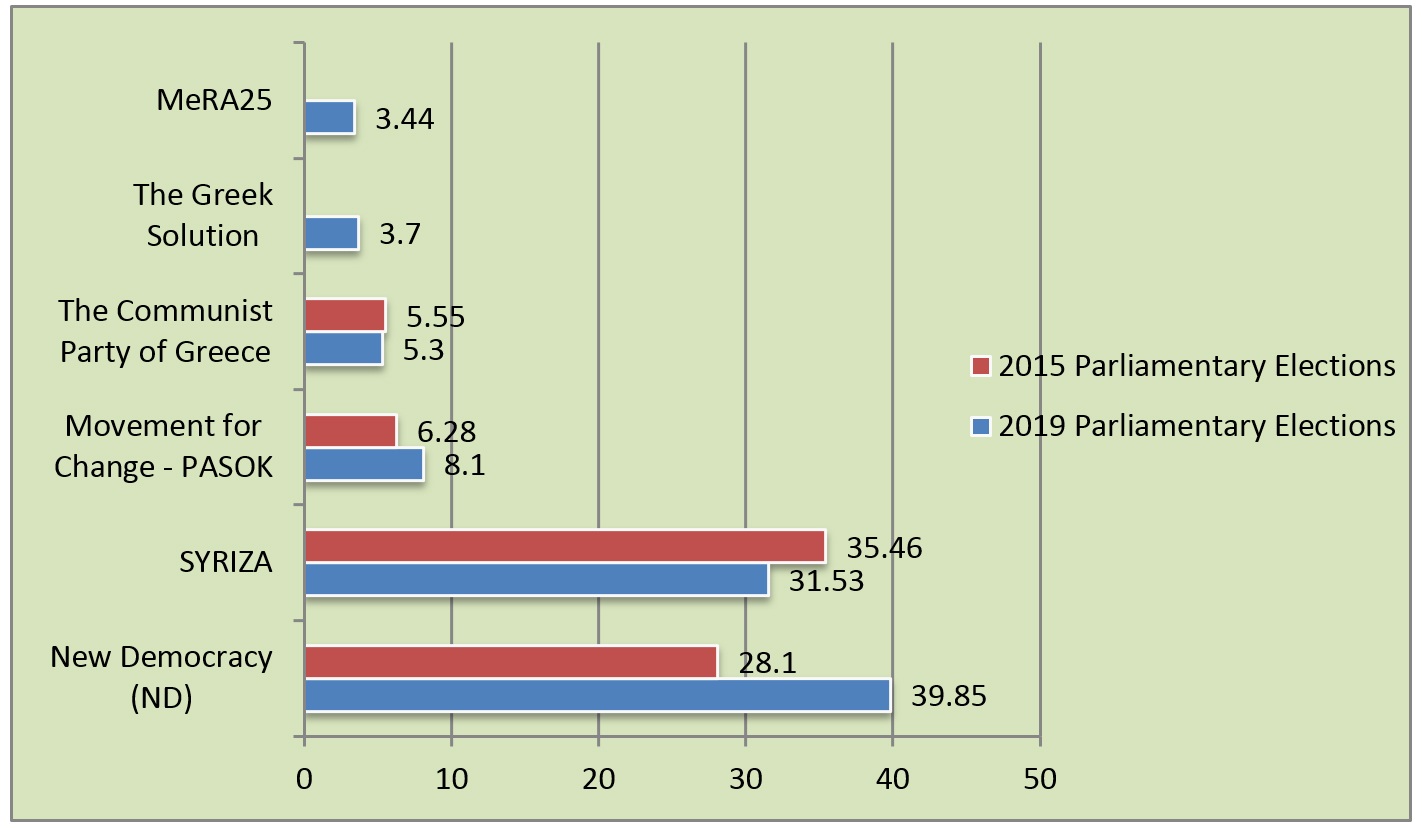

When SYRIZA unseated the New Democracy in January 2015, party’s anti-nationalist credentials were seen as a positive sign for the solution of Greece’s bilateral disputes with its neighbors. However, the expectations for major regional initiatives were extremely low due to the demands of domestic politics. Despite low expectations, the SYRIZA-led government found the political courage to tackle sensitive national issues at a considerable electoral cost.

The then Minister of Foreign Affairs, Nikos Kotzias underlined the need for an active foreign policy in the region that will bring a more collaborative spirit. In that context, he articulated the solution of chronic problems, whose perpetuation had damaged Greece’s interests in the Balkans, as one of the main leading principles of SYRIZA’s foreign policy. In line with this principle, he tried to close all pending issues with North Macedonia and Albania in an effort to break the impasse in relation with them.

The will to resolve the deep-seated and open issues that collides bilateral relations with neighboring Albania and the constructive engagement with North Macedonia for a compromise to the name issue as well as with Kosovo for stronger cooperation were crucial indicators of Greece’s delicate foreign policy shift in the Balkans.

The intense diplomatic engagement between Athens and its northern neighbors not only did much to live up to Greece’s traditionally active role in the Balkans but it also started to bear other significant fruits. The biggest success of this interaction is the Prespa Agreement which put an end to the diplomatic riddle over the name conundrum turning over a new page in Athens-Skopje relationship.

Flirtation with populist nationalism a cause for great concern

Greek political class did not manage to reach a political consensus over the Prespa Agreement. On the contrary, the political debate escalated as the then government and opposition became embroiled in an inflammatory rhetoric over the benefits or not of the agreement. While in opposition, the New Democracy rejected the deal voting against its ratification in the Greek parliament presenting this decision as the will of the vast majority of the Greek people.

Now, under New Democracy government, the future of the Greece-North Macedonia Prespa Agreement remains uncertain. New Democracy leader, Kyriakos Mitsotakis not only is against it, but most importantly while in opposition he put the issue into a nationalist and patriotic gear considering the deal between Athens and Skopje as an act of betrayal to Greece.

This tactic can be considered as an action of New Democracy to reap benefits in the domestic political competition. This approach left little space for rational argumentation in the public debate and fuelled nationalist tendencies in the country, complicating further Mitsotakis’s task to deal now from the position of Prime Minister with the future implementation of the agreement.

Therefore, this nationalist rhetoric enhanced ND’ image as a force that is “more patriotic” than SYRIZA improving the image of his leader as a visionary pioneer with regards to national issues.

Now, with the New Democracy return to power, the newly established government has to preserve a difficult equilibrium by addressing this very sensitive issue in a very measured way, recognizing the important of not angering Greek people especially ND’s right-wing voters by seeming too lenient, while preserving good relations with North Macedonia and at the same time not upsetting Greece’s western allies who strongly support the agreement as a pillar of stability in the region.

Nevertheless, if one looks into the first steps of the newly elected government compromise rather than rupture or intransigence appear to be the rule. The declaration of Greece’s new Prime Minster that the New Democracy will respect the Prespa Agreement seems to be in this direction. The adoption of this moderate stance after the elections seems to eliminate any possibility for radical modification on Greece’s official position in relation to the agreement.

The risk of losing his reputation abroad, where the popularity of his main political opponent Alexis Tsipras has increased significantly mainly because of the name deal, may corral Mitsotaki from adopting any radical action on the issue.

However, any soft approach towards the issue will anger the million of Greek people and ND’s electorate damaging his reputation at home. The statement of Mitsotaki that his government will work to improve aspects of the agreement that are currently not in Greece’s interest may be interpreted as an effort to protect his reputation and satisfy his domestic audience.

Keeping the international-domestic equilibrium will be a real challenging task for him especially after the emergence of a new far-right political party in Greece’s political landscape. Kyriakos Velopoulos’s Greek Solution has a nationalist platform geared towards the patriotic vote. He has already started to criticize ND officials for toning down their rhetoric against the Prespa Agreement characterizing the party as insufficiently patriotic, with the intention to make gains from the ND far-right electoral base.

In any case, the rise of populist nationalism is a very worrying phenomenon. If the new government continues to flirt with nationalistic resentments, it will put the new positive momentum in the Balkans at risk.

Agreement’s implementation intractably linked to accession negotiations

In the coming months, all eyes in Greece will be in the implementation of the Agreement, a development that will determine Greece’s further steps in relation to the accession of North Macedonia into the European Union (EU). The scenario of blocking the accession negotiations with North Macedonia in October does not seem realistic, since Athens may find it more beneficial to actively promote its interests during the negotiations of each chapter. ND officials consider that the chapters negotiation process will create the necessary room for corrections or improvements in parts of the agreement that according to them goes against Greece’s national interests.

It is likely that Western mediators actively wielding carrots and sticks will be the only hedge against the problems that could prolong North Macedonia’s accession process. In that case, the stick would be related to the full implementation of the agreement and to the address of outstanding issues not touched by it, and the carrot North Macedonia’s closing of EU accession chapters. It falls to Athens to deal with this issue in a very measured way without being perceived as standing in Skopje’s way towards the EU.

A basket of problems that complicates Albania’s EU accession process

The Greek diplomacy should also maintain a delicate balance of keeping Albania’s European perspective opened, while trying to resolve bilateral issues. During the last 5 years, Athens’s relations with Tirana followed a more cooperative track with many high-level contacts which have led to the establishment of joint expert meetings where bilateral open issues were discussed in details.

The both sides were negotiating solutions for these thorny issues through the finalization of a mechanism that will result in a package agreement. Bilateral issues were categorized on different baskets with the principle that nothing has been agreed as long as there is no agreement to all issues.

Through this policy of small steps Tirana and Athens set the train in motion again but the train never reached its final destination. The resignation of the then Minister of Foreign Affairs and the internal tensions over the deal with North Macedonia left the completion of the agreement with Albania in a pending status.

The main concern now is whether the new government could reverse this positive political momentum or will continue the progress their predecessors left. New Democracy has strongly criticized the way that SYRIZA was negotiating with Albania. ND politicians have raised doubts about the transparency of the all process.

The mixed messages coming for ND officials does not lead to a clear conclusion of whether the new government will continue to negotiate all pending issues with Albania: the unresolved maritime dispute, the cemeteries of Greek soldiers in Albania, the technical state of war still in place and the Cham’s claims of their confiscated property. So far, ND has remained adamant in Albania’s demands considering the maritime deal agreed by its officials a non-negotiable issue, turning down Tirana’s claims over the existence of war law and rejecting to include in the table of negotiations the non-existent for them Cham issue. There is thus an elevated risk these issues to remain unresolved for a long time.

However, Athens knows that the longer the open issues remains at limbo, the more the danger increases of these issues being hijacked by extremist forces and this is not profitable for none of the states. Therefore, the new government will probably link the solution of pending issues with the fate of the ethnic Greek minority in southern Albania.

Greek minority: a barometer of Athens-Tirana relations

The safeguard of the Greek minority rights constitutes a significant foreign policy objective of Greece. ND has directly connected the question of Greek minority rights with Greek support for Albania’s European perspective. Athens has said Albania’s EU aspirations may be compromised if Tirana fails to protect minority rights, encouraging speculations the new government to block Albania’s start of accession negotiations in October.

During a meeting with Greek minority representatives in Athens, Kyriakos Mitsotakis made clear that the progress in Tirana-Athens bilateral relations and the opening of EU accession negotiations will depend on the respect of the Greek minority’s property rights in Albania as well as on the Albanian government’s willingness to abolish the so-called minority zones.

It seems that the new government will wait for Tirana’s concrete actions towards this direction to give the green light in October. If Athens is not convinced, it will reject the opening of accession negations with Albania following the example of other Member States such as the Netherlands and France which have declared to do the same depending on the progress made in the five key priority areas.

Athens has wider strategic interests in promoting cooperation and the European integration of Albania, but frictions over minority rights cannot be precluded as uncontrolled local problems evolve especially in the predominantly ethnic Greek town of Himara, which plays a hugely disproportionate role for its size in Greek-Albanian relations.

Tensions and ethnically related incidents do occur, particularly in Himara. Yes it is in neither side’s interest to allow them to sour relations at the international level between Athens and Tirana, and this should exercise a powerful moderating effect.

Rejecting Albania’s EU accession dreams is not profitable for Greece. If the planned extension of EU membership extension to Albania is not becoming a reality or is being delayed, the country will suffer a long term political uncertainty and the emergence of an enlarged Albanian state will become even more likely. Therefore, Greece will have the very challenging task to pressure Albania over sensitive national issues keeping at the same time Tirana’s European path in track.

In the light of recent developments, the prospect for opening accession negotiations for Albania is becoming significantly more distant.

Kosovo: non-recognition but stronger cooperation

Although Greece remains one of the five EU member states that have not recognized Kosovo’s independence, Athens has followed a policy of engagement with Pristina and bilateral governmental communication has been quite intensive. It is exactly this policy of constructive cooperation that has made New Democracy more popular among Kosovars.

It was the previous government of New Democracy that gave the first positive signals to Kosovo when it agreed to put Schengen visa stamps on Kosovo citizens’ passports. One other highly indicative example of this positive momentum is the agreement that was signed in March 2013 between the then Greek Minister of Foreign Affairs Dimitris Avramopoulos, a prominent figure of ND party, and his counterpart from Kosovo, Enver Hoxhaj. The agreement set the stage for the establishment of a Kosovo Liaison Office for Economic and Trade Relations in Athens, a decision not having implemented yet.

ND has no reason to abandon this policy of engagement with Kosovo remaining highly supportive of increased cooperation between Pristina and Athens, with a particular emphasis on strengthening economic relations and trade. However, the possibility of the new government to recognize Kosovo is extremely low as long as Pristina has not resolved its dispute with Serbia, in a way that is fully satisfactory for the latter. In essence, ND will hold a waiting stance allowing for the EU to conclude its conflict resolution initiatives vis-a-vis Serbia and Kosovo, before decides on its final position regarding Kosovo’s recognition. Despite the non-recognition status, there is quite some room for improving and expanding current relations.

There is no doubt that the dialogue between Kosovo and Serbia influences also EU-Kosovo relations. Kosovo’s commitment and constructive approach in the dialogue is seen to be a precondition for strengthening its path towards European integration. Athens has always supported the European perspective of Kosovo and the strengthening of EU-Kosovo relations as a necessity for the stability of the entire region. Keeping Kosovo on this track would be in the interest of Greece excluding the scenario of Kosovo’s unification with Albania.

Outlook

The new Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis promised to return Greece back to normality offering a fresh perspective in all aspects of country’s political life. But no one is quite sure what that perspective actually entails and how fresh or old it really is. The fact that New Democracy did not diverge from domestic populism could be interpreted as a return to a more nationalistic foreign policy. If this is the case, Greece will stick again in the past, a development that will isolate Athens weakening significantly its international position. However, the Greek leadership has not the luxury to lose the great historic opportunity that has been created in the Balkan region after Prespa Agreement. On the contrary, it seems that the new government will take the advantage of this new momentum through the adoption of a more moderate foreign policy to reorient Greek interests towards the Balkans. The revision and the modernization of Greece’s foreign policy in the region would be the best scenario for returning to normality. The ideal normality will be to the large extent oriented towards the closing of all pending issues inherited by the past allowing Greek diplomacy to invest more capital in other more pressing issues in the east.