ALTIN GJETA

Introduction

European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) established in 1951 after the end of World War II has evolved through two axes, deepening and widening integration into what we know today as the European Union (EU). The horizontal axis of the EU integration is known as the enlargement process, through which the EU has expanded its territory “from Mediterranean shores to the Baltic Sea and from the Atlantic to the Black Sea, in just over four decades”.[1] Enlargement of the then European Economic Community was narrowly put into the Treaty of Rome, Article 273 which asserted that “any European state may apply to become a member of the Community”.[2] Since then, the membership of the EU has increased drastically from 6 countries originally to 28 members.[3] Admittedly from these figures, enlargement may be considered one of the most successful policies of the EU. “The enlargement from a Community of six member states to a Union of 27 is widely regarded as the EU’s greatest policy triumph”.[4]

In that regard, the EU enlargement has been extensively theorized by field scholars and practitioners. They have applied different theoretical approaches in explaining it, from neofunctionalism to intergovernmentalism and constructivism. Needless to say, each of them has given a good contribution in elucidating such a complex aspect of the EU integration. However, this paper will argue that intergovernmentalism offers a much more comprehensive theoretical approach in understanding the EU enlargement. Although one could argue that the EU enlargement process from the first round in 1973 with the UK, Ireland and Denmark to the last one with Croatia in 2013 has bureaucratically evolved to a more supranational level, we hold that the key decision makers have remained the same actors, member states of the EU.

The paper will proceed as follows. In the first part we will give a brief introduction of intergovernmentalism. This section will elaborate shortly the main tenets of intergovernmentalism in order to illuminate the reasons why member states have supported and at the same time remained the core actors of the EU enlargement. The second section will elaborate the decision-making process of the EU on the enlargement policy. Here we will argue that despite of the changes over the time in the institutional architecture of the EU with regard to the enlargement policy, the process in itself has largely remained under the control of member states.

Intergovernmentalism in short

Until the 1960-s the dominant theoretical approach towards the EU integration has been supranational theory or as it has largely been known as neofunctionalism. The most prominent scholar of neofunctionalism is Haas, whose argument is that “the creation of a central authority would lead to the emergence of supranational trade associations, labor unions and political parties that would increasingly pursue their interest at the European level”.[5] Thereby, neofunctionalists’ paradigm holds that national states are not the only actors of the international stage and that the EU integration proceeds through the spillover concept. Schmitter in Haas and the legacy of neofunctionalism points out that “states are not the exclusive and may no longer be the predominant actors in the regional and international system”.[6] However, the empty chair crisis during the mid-1965-s when the French President Charles de Gaulle boycotted the European institutions showed that national states matter.

The emergence of intergovernmentalism is precisely linked with the enlargement process of the EU during the 1960-s. French President de Gaulle vetoed twice the UK application for Community membership which blocked the first attempt of the Union to expand with new countries. France returned to the EU institutions after the so-called Luxemburg Compromises in 1966, where the unanimity voting was introduced within the European Council. This led to the emergence of the intergovernmentalism, prominently put forward by Hoffman who “argued that nation states would remain the key players in international politics”.[7] Intergovernmentalists hold that the national states are unitary actors in international relations that seek their own national interest. As Cini maintain “intergovernmentalism is drawn from classical theories of international relations, most notably from realist or neo-realist accounts of inter-state bargaining”. [8]

Leaving the general perspective of intergovernmentalism and coming back the EU integration, intergovernmentalism assumes that member states are the most important actors within the EU which cooperate and co-ordinate with each other and external actors upon a cost-benefit analysis. The main aim in engaging in this qualitative cost-benefit analysis is to protect national interests.[9] This cost-benefit analysis is closely interlinked with the utility concept (economic, political and security advantages). “Utility refers to an effort to find efficient solutions to concrete problems or dilemmas. Policy-makers seek legitimisation by achieving an output that could be seen as beneficial to given interests and preferences”.[10] In this context, intergovernmentalists maintain that member states tend to retain their sovereignty and act as the main players of the EU integration in their own interests. Bache et al, synthesising intergovernmentalism argue that national governments were unique actors in the process of EU integration […] they controlled the nature and pace of integration guided by their national interests.[11] However, as the EU integration changed over the years through deepening and widening axes, the theoretical perspectives explaining it evolved as well. Classical intergovernmentalism of Hofmann moved to liberal intergovernmentalism of Moravcsik and finally to the new intergovernmentalism of Bickerton.[12] “Liberal intergovernmentalism, as proposed by Andrew Moravcsik, holds that the steps towards further integration in the 1980-s and 1990-s should be best understood as a result of the convergence of member states preferences”.[13]

While the EU integration progressed faster and the enlargement process experienced its first two rounds, member states pooled more sovereignty to the EU supranational institutions, namely to the European Commission and European Parliament. Nonetheless, Moravcsik argues that this is mostly done to facilitate cooperation and legitimate decision making of member states by strengthening the power of governments into two ways: “increase the efficiency of interstate bargaining and strengthen the autonomy of national political leaders vis-à-vis particularistic social groups within their domestic polity”.[14] Whereas, Bickerton, Hodson and Puetter call for a new intergovernmentalism after the Maastricht era where the EU integration is pursued through policy co-ordination between member states […] but it consistently avoids transferring more powers to traditional supranational bodies – notably the Commission and the Court”.[15]

However, the aim of this paper is not to analyse the nuances of intergovernmentalism per se but its relevance in explaining the EU enlargement. Therefore, in sum we would like to re-stress that the core element of intergovernmentalism is that member states are the most important political actors, who seek to maximize their benefits throughout the integration process of the EU. We shall see below that they have been and continue to remain the key decision makers of the EU enlargement over the years.

The process and actors

Although the EU has expanded its membership progressively, enlargement was not considered a proactive policy of the Union in its very beginning. Interestingly, the EU has never asked other countries to join the Union, but it has been opened if they would like to become members. Thus, Treaty of Rome vaguely foresaw this in the Article 273, which promulgate that “any European state may apply to become a member of the Community”.[16] While the EU started to enlarge with other countries, it was deliberatively tailored into a more active and detailed policy. Hence, Article 49 of the Treaty on European Union asserts that “any European State which respects the values referred to in Article 2 and is committed to promoting them may apply to become a member of the Union”.[17] Based on these two articles, the EU has drastically increased its membership through the enlargement process.

Nevertheless, although the EU enlargement has evolved throughout the time, “it still remains largely under control of member states”.[18] This is mostly due to the institutional structure of the EU where member states interact intergovernmentally. The enlargement cycle of the EU begins with the approval of the member states in the European Council and ends with the ratification by national parliaments or else as it is regulated by their respective constitutional requirements. Thereby, “when a potential candidate approaches to the EU, the first step is for the European Council to consider whether the application is acceptable in principle”.[19] This is an important stage because it sets the prospect and the pace of the process. It is already a well-known fact now that the first enlargement of the EU was blocked by a member state in the beginning of 1960-s. Nugent in his seminal book The Government and Politics of the European Union asserts that “the first enlargement of the Community could, in fact, have occurred much earlier than it did, had the President de Gaulle not opposed UK application in 1963 and 1967”.[20]In doing so, the President of France acted based on his national interest, because regarding his point of view, the UK would unsettle the Franco-German alliance.

However, intergovernmentalists do not assume that supranational institutions do not play any significant role. For instance, if the European Council is positive to a potential candidate, it forwards its opinion to the European Commission, which is responsible for monitoring the accession process and formulates an opinion whether to open or not the accession negotiations with a candidate country. It fulfills this mission through the Directorate-General (DG Near) which would act as gatekeeper, deciding when countries have fulfilled the criteria […] and whether they are ready to move to the next stage”.[21]

Nonetheless, “Commission’s opinion is not legally binding on the Council, which decides unanimously on whether to open the accession negotiations with an applicant”.[22] During southern enlargement, the Council overruled the negative opinion of the Commission towards Greece candidacy. “The Commission issued a formal opinion which stated that Greece wasn’t economically ready to start accession negotiations and instead it proposed a pre-accession period of unlimited duration”.[23] At that time Greece was coming from a military dictatorship and it insisted to join the Union on grounds that this would help it to consolidate its new democracy and forge ties with the Western Alliance. “The Council of Ministers was sympathetic to these arguments and rejected Commission’s proposal. Membership negotiations were opened in July 1976 and Greece became full member of the Community in 1981”.[24] This case shows the importance of member states as the key decision makers of the EU enlargement. In this vein, Juncos and Perez-Solorzano Borragan point out that “from the beginning, enlargement has been an intergovernmental policy, strongly in the hands of member states”.[25]

Starting from a neofunctionalist/supranational perspective one could argue that after the Maastricht Treaty European Commission and European Parliament’s (EP) powers were proportionately increased vis-à-vis European Council and the Council. The introduction of the Copenhagen criteria in 1993, accordingly the political, economic and acquis-communautaire, were set to increase the role of the Commission over the enlargement process. Admittedly, conditionality turned enlargement into a more bureaucratic and therefore more incremental process. Sedelmeier posits that “although the treaty rules for enlargement identify member states as central actors, in practice European Commission has played a very significant role in each of the main phases of enlargement process, association, alignment and accession negotiations”.[26] However, from an intergovernmentalist’s perspective, introduction of the Copenhagen’s criteria tells more about the bargaining process between member states. Juncos and Perez-Solorzano Borragan contend that “the establishment of clear membership conditions satisfied both for and anti-enlargement camps”.[27] For instance, during the third round of the enlargement (EFTA) applicant states were quite prepared politically and economically therefore they were seen as a benefit in paving the way for future expansion of the EU. “The EFTA applicants were wealthy and potential net contributors to a common budget that would come under much greater pressure if the Central and Eastern European countries (CEESs) were eventually accepted”.[28]

In the spirit of the institutional changes that Maastricht Treaty brought in, EP’s power “was increased in several areas, notably in respect to the making of legislation under a newly created co-decision procedure”.[29] Whereas, Qualified Majority Vote procedure in the Council (QMV) was extended. Article 16 on the Treaty of the European Union (TEU) envisioned that “the Council shall jointly with the EP exercise legislative and budgetary functions. It shall carry out policy-making and coordinating functions as laid down in the Treaties. The Council shall act by a qualified majority vote except where treaties provide otherwise”.[30] However, enlargement was not crucially affected by those changes because they fell under the scope of the so-called “high” politics (Common Foreign and Security Policy). In this regard though the power of the European Commission and the EP increased significantly, yet enlargement remained under much more control of member states. Thereby, Article 49 on the TEU promulgated that “the applicant state shall address its application to the Council, which shall act unanimously after consulting European Commission and after receiving the consent of the EP which shall act by a majority of its component members. This agreement shall be submitted for ratification by all states in accordance with their respective constitutional requirements”.[31] This meant that the EU enlargement would proceed with the consent of the EP, but the principle of the unanimity within the Council and the ratification procedure by member states’ national parliaments shows once again that the real decision makers are Union’s member states.

Plausibly European Commission’s proactive role in the EU enlargement towards CEESs and Western Balkans was increased over the years. It is essentially strengthened respectively through the Association Processes (AP) and Stabilization and Association Process (SAP) which at some extend gave European Commission a leadership role in the process. However, member states still continued to ‘dictate’ the pace and the geography of the process. The Eastern enlargement has been one the most challenging process of the EU, concerning its size and the preparedness degree of candidate countries. Nevertheless, the EU proceeded toward Big Bang enlargement through an intergovernmental process. With regard to this, it is true that socio-economic, security and value-based factors were at stake. Constructivists would argue that values played a crucial role over the decision of the EU to enlarge with the CEESs. For instance, Schimmelfenning asserts that “liberal norms and values of the European Community are the basis of the membership criteria and commit member states to the accession of states that share the collective identity and adhere to its constituent values and norms”.[32]

On the other hand, while there is no doubt that a measure of idealism played a supporting role in the EU’s decision to enlarge, we would do well to consider the context of national interests and power. It is no secret that Germany, the UK and Denmark were the biggest supporters of the Eastern enlargement as it added to the inner market 100 million consumers in fast growing economies. Thus socio-economic factors informed preference formation of member state because countries that benefitted the most from market expansion, such as Germany and the UK, were supportive of rapid and all-inclusive enlargement”.[33] In this context, although some countries fell behind with the regard to the accession criteria such as Bulgaria and Romania, European Council decided in 2004 summit to give the green light for the signing of the accession treaties with both states.

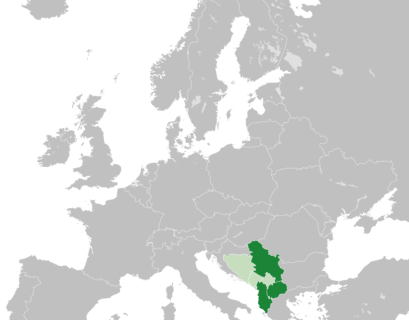

The last round of enlargement is the ongoing process with the Western Balkans (WB). So far, only Croatia has joined the EU in 2013, whereas six other countries are currently at different stages in the process. The European Commission’s role in the EU enlargement with the WB has been and continues to be fundamental because of two reasons: first, WB countries have shown little progress in meeting the accession criteria and second, after the financial crisis member states have been reluctant to enlarge due to increasing public’s skepticism in expanding with new states. In this context, Commission emerged as the leading actor of the process. It has set the agenda and constantly pushes forward the process through monitoring and giving recommendations to candidate and potential countries.

In 2018 and 2019 European Commission unconditionally recommended the Council to open accession negotiations with Albania and North Macedonia. “The European Commission recommends that the Council decides that accession negotiations be opened with Albania in light of the progress achieved, maintaining and deepening the current reform momentum”.[34] Nonetheless, the Council’s meeting in June 2018 postponed the opening of negotiations as France and the Netherlands were skeptic on the progress being made by candidate countries. “The Council recalls that the decision to open accession negotiations with Albania will be subject to completion of national parliamentary procedures and endorsement by the European Council and will swiftly thereafter be followed by the first Intergovernmental Conference by the end of 2019, depending on progress made”.[35] The same decision was taken last year when France vetoed the opening of the accession talks with Albania and North Macedonia on the grounds that the process has become obsolete and therefore it should be reformed.[36] This shows once again that member states are the key decision makers of the EU enlargement. Moreover, they are even claiming back their power in the enlargement policy which indicates that it will continue to remain an intergovernmental bargaining process in the hands of member states.

Conclusion

The EU enlargement is a complex process which includes a wide range of actors, from member states to the EU supranational institutions. From the first round to the ongoing one with the WB, the process has evolved with major implications on the political, economic and geographical landscape of the EU. Therefore, it is difficult to fully explain it solely from a theoretical perspective. However, as we have seen throughout this paper it can be better grasped through the lens of intergovernmentalism. The EU enlargement has from the beginning been much more under control of the member states as they supported or blocked it based on their national interests. Thus, the first round of enlargement was delayed because France saw UK as a threat to its national interests, whereas during the second round, Greece was granted accession despite the Commission’s negative opinion on its progress in meeting outlined criteria. In this regard, the EU enlargement was seen mostly as a bargaining game based on a cost-benefit analysis.

It is undeniable that supranational institutions matter for intergovernmentalists as well, but they see them merely as facilitators of the integration rather than as real decision-makers. Thereby, the treaties on the institutional structure rule out more power to member states pertaining to the enlargement policy. As the EU expansion continued, European Commission and EP’s power were significantly increased and strengthened pertaining to the enlargement policy. Particularly, European Commission took a crucial role in the EU enlargement after introduction of the Copenhagen criteria. The process became more incremental and therefore Commission’s role in monitoring the association process of candidate countries was increased substantially.

However, this falls short vis-à-vis unanimity voting system in the European Council and the Council. This is reflected throughout the enlargement process where member states emerged as the key decision makers. They have set the pace and geography of the process during the Eastern and Western Balkans enlargement despite increased role of the Commission. In addition, EP’s boosted role as co-legislator with the Council was out of the scope with regard to the enlargement policy. In order to advance towards EU accession a candidate country needs Council’s consent and ratification of member states’ parliaments based on their constitutional requirements. Therefore, the EU enlargement cycle starts with the approval of member states in the European Council and ends up with their final ratification which indicates that it has stubbornly remained an intergovernmental process.

Altin Gjeta holds a Master of Arts in International Relations and Democratic Politics from University of Westminster, London.

References

Bache et al. Politics in the European Union. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Bickerton, Christopher J., Hodson, Dermot and Puetter, Uwe. “The New Intergovernmentalism: European Integration in the Post-Maastricht Era.” Journal of Common Market Studies, 53, no. 4, (2015): 703-722.

Cini, Michelle. “Intergovernmentalism” in European Union Politics. edited by Michelle Cini and Nieves Perez-Solorzano Borragan, 65-79. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

European Commission Staff working document. Albania 2018 Report. Communication on EU Enlargement Policy: final report, 2018. Strasbourg. European Commission. Available from http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_MEMO-18-3403_en.htm [Accessed 23 December 2018].

European Commission Staff working document. Albania 2019 Report 260. Communication on EU Enlargement Policy: final report, 2019. Strasbourg. France.

General Affair Council. Council conclusions on enlargement and stabilization and association process: final report, 2018. Brussels. Council of the European Union. Available from https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/35863/st10555-en18.pdf [Accessed 24 December 2018].

Juncos, Ana E. and Perez-Solorzano Borragan, Nieves. “Enlargement” in European Union Politics, edited by Michelle Cini and Nieves Perez-Solorzano Borragan, 227-241. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Library of the European Parliament. EU Accession procedure, 2018. Available from www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/bibliotheque/briefing/2013 [Accessed 20 December 2018].

Moravcsik, Andrew. Preferences and Power in the European Community: Liberal Intergovernmentalism Approach. Journal of Common Market Studies, 31, no. 4 (1993): 473-519.

Nugent, Neill. The Governance and Politics of the European Union. 8th ed. London: Macmillan Education, Palgrave, 2017.

Peel, Michael and Hopkins, Valerie. “France objects to North Macedonia and Albania EU accession talks.” Financial Times, October 15, 2019. Available from https://www.ft.com/content/fce9e9a0-ef36-11e9-ad1e-4367d8281195 [Accessed 10 February 2020].

Sedelmeier, Ulrich. “Enlargement: Constituent Policy and Tool for External Governance”, in Policy Making in the European Union, edited by Helen Wallace, Mark A. Pollack and Alasdair R. Young. 7th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015.

Sjursen, Helen. Why Expand? The Question of Legitimacy and Justification in the EU’s Enlargement Policy. Journal of Common Market Studies, 40, no. 3, (2002): 491–513.

Treaty on European Union, Maastricht, 1993. C 326/13.

Treaty of Rome, 1957. Available from https://ec.europa.eu/romania/sites/romania/files/tratatul_de_la_roma.pdf [Accessed 18 December 2018].

Zimmermann, Hubert and Dur, Andreas. Key

Controversies in European Integration. London: Macmillan Education,

Palgrave, 2016.

[1] Ana E. Juncos and Nieves Perez-Solorzano Borragan, “Enlargement” in European Union Politics, ed. Michelle Cini and Nieves Perez-Solorzano Borragan (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 228.

[2] See Treaty of Rome (1957)

[3] The EU membership dropped to 27 states on 31st of January 2020 when the UK officially left the Union.

[4] See Library of the European Parliament, EU Accession procedure (2018).

[5] Hubert Zimmermann and Andreas Dur, Key Controversies in European Integration (London: Macmillan Education, Palgrave, 2016), 5.

[6] Philippe C. Schmitter, “Ernst B. Haas and the legacy of neofunctionalism”, Journal of European Public Policy, 12, no. 2, (2005): 259.

[7] See Zimmermann and Dur, Controversies in European Integration, 5.

[8] Cini, “Intergovernmentalism”, 68.

[9] Ibid

[10] Helene Sjursen, “Why Expand? The Question of Legitimacy and Justification in the EU’s Enlargement Policy”, Journal of Common Market Studies 40, no. 3, (2002), 495-497.

[11] Bache et al, Politics in the European Union (4th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015).

[12] Christopher J. Bickerton, Dermot Hodson and Uwe Puetter, “The New Intergovernmentalism: European Integration in the Post-Maastricht Era”, Journal of Common Market Studies 53 no. 4, (2014), 703-722.

[13] Zimmermann and Dur, Controversies in European Integration, 5.

[14] Andrew Moravcsik, “Preferences and Power in the European Community: Liberal Intergovernmentalism Approach”, Journal of Common Market Studies 31 no. 4, (1993). 507.

[15] Bickerton, Hodson and Puetter, “The New Intergovernmentalism”, 704.

[16] See Treaty of Rome (1957).

[17] See Treaty on European Union, Maastricht (1993).

[18] Juncos and Perez-Solorzano Borragan, “Enlargement”, 228-234.

[19] Bache et al, “Politics in the European Union”, 519

[20] Neill Nugent, The Governance and Politics of the European Union (8th ed. London: Macmillan Education, 2017), 58.

[21] Juncos and Perez-Solorzano Borragan, “Enlargement”, 232

[22] Ulrich Sedelmeier, “Enlargement: Constituent Policy and Tool for External Governance”, in Policy Making in the European Union, ed. Helen Wallace, Mark A. Pollack and Alasdair R. Young, (7th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2015), 422.

[23] Neill Nugent, “The Governance and Politics of the European Union”, 60

[24] Ibid, 60

[25] Juncos and Perez-Solorzano Borragan, “Enlargement”, 231

[26] Ulrich Sedelmeier, “Enlargement: Constituent Policy and Tool for External Governance”, 424

[27] Juncos and Perez-Solorzano Borragan, “Enlargement”, 231

[28] Bache et al, “Politics in the European Union”, 526

[29] Neill Nugent, “The Governance and Politics of the European Union”, 82

[30] Treaty on European Union, Maastricht 1993, C 326/13, Official Journal of the European Union, (2012).

[31] Ibid

[32] Michelle Cini and Nieves Perez-Solorzano Borragan, “European Union Politics”, 236

[33] Ibid

[34] See European Commission report 2018 and 2019.

[35] See General Affair Council’s conclusions on enlargement and stabilization and association process: final report. Brussels. Council of the European Union. Available from https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/35863/st10555-en18.pdf [Accessed 24 December 2018].

[36] Michael Peel and Valerie Hopkins, “France objects to North Macedonia and Albania EU accession talks”, Financial Times, October 15, 2019.