ELTION MEKA

Abstract

The Western Balkans is arguably the world’s biggest case-study of internationally-led democratization. Yet despite the great attention and resources dedicated to the region, international efforts have not produced the outcome we would expect. Democratization is at a standstill or even regressing and the stalled process of European enlargement has all but diminished any chance of substantial change. The regions stagnated process of democratization is, from the perspective of the international dimension of democratization, surprising. Public support and trust in the European Union and other Western-led international organization is much higher in the region than Western Europe and political parties have closely aligned their political programs with the accession criteria. Under such conditions, we would expect the region to have performed much better. This article will therefore take stock of the European integration literature on the Western Balkans in order to show the ways in which the European Union is aiding democratization in the Western Balkans.

Introduction

At the time of writing the European Council has just adopted a draft decision which gives Albania and North Macedonia the green light to commence accession negotiations. This is a welcoming sign to the citizens of the Western Balkans (WB) after years of delay. While Serbia and Montenegro have already began negotiations, the delays with Albania and North Macedonia had forced many to question to credibility of the enlargement process for the WB.[1] Democracy on the other hand, has either stalled or is regressing as a prominent scholar of the region has recently highlighted.[2] In this paper we seek to explore the relationship between European integration and democratization by asking how does European integration effect democracy in the WB.

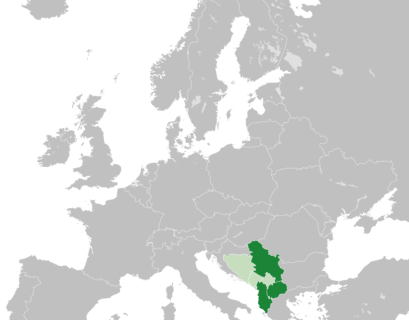

The role of European integration (and international forces more generally) in shaping transitional politics is perhaps one of the most widely researched topics in political science and international relations literature. And it is in this respect, that the EU has been labeled as the prime benefactor of new democracies in Europe.[3] The WB, however, seem to have resisted the effects of European integration. Despite being offered a credible membership perspective, apart from Croatia which became the latest EU member state in 2013, the region has stagnated. Bosnian and Herzegovina remains emblematic of a state with significant challenges in overcoming its ethnic divisions; Kosovo remains a contested state; North Macedonia has only recently been able to overcome its longstanding name dispute with Greece; Albania epitomizes most of the challenges transitioning societies face; Serbia has yet to come to terms with its recent past; meanwhile Montenegro may represent the only beacon of hope for the region. While each of these cases are fraught with peculiar challenges of their own, they have all been and continue to remain under the influence of integration process.

There is substantial evidence in support of the claim that international actors help move democracy forward, be it the post-communist world, Latin America, or the global south more generally.[4] While different international actors promote different kinds of democracy and through different means, the literature is conclusive on these distinctions and has consistently shown the superiority of conditional approaches.[5] Conditional approaches here refer to cases where the recipient state has to undertake reforms before receiving a reward, as opposed to incentivized approaches where a recipient state receives an initial reward with the hope that it will implement democratic reforms in order to continue receiving aid. Meanwhile, by democracy promotion we mean “the processes by which an external actor intervenes to install or assist in the institution of democratic government in a target state.”[6]

The EU’s enlargement policy which requires applicant candidate states to undertake reforms before moving closer to eventual full membership is a prime example for exploring the effects of the conditional approach. Yet, as this article will show, even this approach has its limitations, particularly when democracy promotion is confronted with simultaneous domestic challenges that may not necessarily require the same strategies and instruments. This is the case in the WB where democratization, reconciliation, and state building are developing side by side, but may not necessarily be complimentary with one another. In the remainder of the article, we will first provide a short overview of the democracy and democracy promotion literatures. Second, we provide an overview of the EU’s presence in the region by highlighting some of its achievements and failures. Last, the article concludes by emphasizing the major takeaways as well as highlighting some expectations for the near future.

Democracy and Democracy Promotion

Every democracy has a starting point, a birthday, which in new democracies often represents the country’s first democratic elections. At this point, the pillars of representative democracy are institutionalized into the new democracy’s body of laws. These pillars, first and foremost, refer to political rights and civil liberties such as the right to vote, the freedom of expression, the right to assembly and so on. However, the institutionalization of these right, in the legal sense of the word, does not necessarily secure the new democracy’s future. As the authoritarian and populist trend of the post-2008 global economic recession has shown, institutionalization is not enough in securing democracy. The rise of populism in Europe, the election of Donald Trump to the White House, and the democratic backsliding in some of the EU’s newest member states provide a clear illustration to the limits of institutionalist arguments. It is in this respect, the Linz and Stepan have argued that democracies become consolidate and endure not only when “governmental and nongovernmental forces alike…become subjected to, and habituated to, the resolution of conflict within the specific laws, procedures, and institutions sanctioned by the new democratic process,” but when such institutional changes are associated with behavioral and attitudinal shifts.[7]

It is the attitudinal and behavioral aspects of democracy which today have taken center stage in the study of democracy. Thus, questions such as who supports populist parties, who supports anti-immigration policies, who voted for Donald Trump or Brexit, and how do political parties respond to such changes have become of increasing importance.[8] Transitioning democracies, however, are almost never dealing with a single transition. As Offe and Adler have argued, the post-communist democratic transitions of Eastern Europe evolved simultaneously with the region’s economic transition and process of nation building.[9] The latter is particularly relevant in the WB where the breakup of the former Yugoslavia has led to the creation of seven successor states. The issue that we want to address in this article is to illustrate how democracy promotion is undermined due to the simultaneous promoting of other ideas such as ethnic reconciliation and regional stability.

The WB are ideal testing grounds for such questions for the simple reason that the region has been a major recipient of EU democracy promotion and efforts to restore friendly relations within states and between them. For example, the Stabilization and Association Process (SAP) which serves as the framework for the region’s European aspirations requires that each state first stabilize its relations with neighboring states, and only subsequently accede into the EU. It is under this framework that democracy, reconciliation, and regional stability are promoted. In the remainder of the article we provide an overview of the EU’s presence in the region and how it has been able to shape political developments.

Promoting What?

The body of literature that is democracy promotion has addressed a significant number of questions. Questions that can be broadly stated in the following lines: Who is it that is doing the promoting? What is it that is being promoted? How is the promotion being carried out? Why is democracy being promoted? And what effects are we observing? Most researchers, however, would agree that Western actors promote a liberal version of democracy, consisting of a set of partial regimes, that is, free and fair elections, political rights, civil rights, horizontal accountability, and effective representation.[10] Yet, even within the liberal model we find variation such as the social democratic model of Western Europe and the more liberal American variant. Although, there is some evidence in support of the claim the US to promotes a model of democracy closely linked with capitalism, while the EU is perceived as less ideologically committed by promoting a “fuzzy liberal” model of democracy.[11] Moreover, there are some indications showing that the EU promotes Lijphart’s consensual model of democracy compared to the majoritarian model.[12]

In the last decade, the promotion of democratic governance has also received substantial attention. Democratic governance, however, should not be conflated with democracy itself. As one prominent scholar of the field has pointed out, while democratic governance in not incompatible with liberal democracy, “the promotion of democratic governance does not target the core institutions of the democratic state – the electoral regime, individual rights, and the checks and balances of legislative, executive, and judicial organs. Rather, it focuses on the institutions of sectoral governance” such as transparency, accountability, and participation.[13] Democratic governance in this respect is thought to represent a more technocratic approach to democracy promotion. Some research is even suggesting that the EU has shifted its priorities from the promotion of democracy to the promotion of democratic governance.[14] As we will show below, this trend is worrisome for the WB where the EU’s focus on democratic governance and stability is of particular relevance.

Democracy Promotion Through EU Enlargement

Democracy promotion scholar Richard Youngs has famously stated that the Eastern enlargement of the EU was the most successful case ever of democracy promotion.[15] Besides the strict accession criteria based on the Copenhagen Criteria for membership, what gives EU membership power is the Union’s normative appeal.[16] New democracies seek to join the Union, not only for its economic benefits, but also because accession represents a certain status—of having escaped a country’s communist past and now moving toward a European future. Perhaps a quote from Romanian scholar Alina Mungiu-Pippidi, best illustrates effects of European integration:

“There is no doubt that EU enlargement has been a remarkable success…Not only did the prospect of the EU membership precipitate the reforms that were indispensable for the transformation of [Central and Eastern Europe] CEE states, but since it enjoyed large popular support it also enticed post-communist parties into becoming genuinely pro-EU parties…[and as a result], transitions with an EU prospect seem to be the best: they lead to democracy and prosperity earlier and with fewer uncertainties and risks than any other types of transitions.”[17]

It was the conditional nature of EU accession, however, that led to the success of the Eastern enlargement. CEE states were expected to oblige to a pre-set EU agenda in order to secure membership. In other words, reforms came first, rewards came later. Yet, this approach is not without its limitations. Expected to oblige to a pre-set agenda of rules to which an applicant states had no say in formulating in the first place raises questions about the sustainability of reforms once membership is secured. Interestingly, research has shown that while post-accession compliance with EU rules—rules which have a basis in the acquis (EU body of laws) has been relatively stable—compliance with non-rule-based norms has lagged far behind.[18] The explanation for this observation is equally interesting.

While the EU has a strong infringement procedure for failing to comply with the acquis, the Union’s tools are more limited when it comes to preventing democratic breaches. Beyond the activation of Article 7 of the EU Treaty which suspends a country’s voting rights in EU institutions, there is very little else at the EU’s disposal. Moreover, because the conditional nature of EU accession process forced applicant states to compete over the implementation of a pre-set agenda rather than alternative policies it did not encourage the development of democratic pluralism. In other words, because the pre-accession process prioritized the efficiency of policy adoptions over the legitimacy of such policies, the EU, paradoxically, while acting as a beacon of legitimacy in driving applicant states toward democracy it undermined the development of democratic practices.

Explaining post-accession compliance with democracy becomes even more interesting from the perspective of party politics. There is broad consensus in the literature that European integration had a profound effect on CEE party systems. Not only did the accession process shape political competition, but it also provided the framework though which parties built their political programs. As Vachudova, has argued, “in almost all cases, major political parties respond to EU leverage by adopting agendas that [were] consistent with EU requirements in the run-up to negotiations for membership.”[19] In this respect, former communist, illiberal, and authoritarian parties adjusted their ideological profiles to appear more supportive of integration. However, once accession was secured, these parties then appear to have reverted to their original ideologies, which in many cases had nationalist and authoritarian roots. The theoretical argument here is that the drive toward EU membership helped stabilize political competition and suppressed political tensions, although, once membership was secured, political tensions came to the fore, and political competition was reshaped once more.

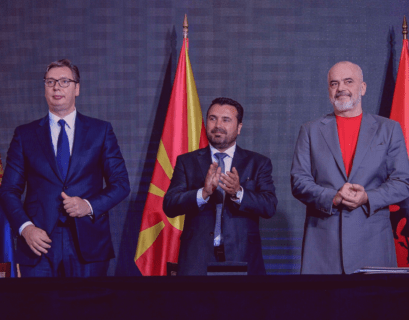

Vachudova who is one of the prominent scholars of this field has recently argued that the process of EU accession is shaping political competition in the WB in a very similar pattern.[20] Former authoritarian and nationalist parties, such as the Socialist Party of Serbia (Slobodan Miloševic’s former party) or the Serbian Progressive Party (a breakaway faction of the nationalist Radical Party) have adopted agendas consistent with the accession criteria. A similar trend is apparent in Montenegro where all major political parties are supportive of EU accession.

Nevertheless, we now know that post-accession is a different story. As Alina Mungiu-Pippidi argues:

“When conditionality has faded, the influence of the EU vanishes like a short-term anesthetic. The political problems in these countries, especially the political elite’s hectic behavior and the voters’ distrust of parties, are completely unrelated to EU accession. They were there to start with, though they were hidden or pushed aside because of the collective concentration on reaching the accession target…Now that countries in the region have acceded to the EU, we see Central and Eastern Europe as it really is—a region that has come far but still has a way to go.”[21]

The above quote may even provide us with insights into why the EU finds it difficult to promote democratic values that are sustainable in the long-run. There is now broad consensus in the scholarly community that the EU’s promotion strategies can be seen as ‘shallow’. The argument here rests on the claim that reforms are more likely to endure when they are accompanied by social learning. However, it appears that the EU’s top-down and technocratic manner of administering the accession process left little room for social learning, and as a result, what we are now witnessing in post-accession CEE is a prime case of ‘shallow Europeanization’. The question that we now turn to is, to what extent can we expect the EU’s influence in the WB to have a lasting and deep effect on values and norms that we associate with liberal democracies?

The EU in the WB

Any analysis of the process of integration must take as a starting point the supply and demand arguments for integration. By supply, we mean a credible perspective for EU membership. Meanwhile, by demand, we mean a desire for membership on behalf of the applicant states. There are a variety of ways through which these factors can be analyzed. For example, official documents and government speeches from member and non-member states can tell us the seriousness to which EU enlargement is being considered. We can also analyze party profiles and determine the extent to which political parties are placing an emphasis on pro or anti-enlargement policies. From a different angle, we can analyze popular views from the perspective of EU citizens or applicant states in order to determine popular desire for enlargement.

There is consensus among the academic and policy communities that after the 2008 global financial crisis the EU entered a phase of enlargement fatigue. This argument suggests that due to a number of internal challenges such as the Eurozone crisis, Brexit, and rising populism, an enlargement perspective became unrealistic in the short term. Indeed, current French President, Emmanuel Macron, has persistently pointed out that there will be no enlargement until the EU decision-making procedures have undergone deep reforms. There is an important distinction in the European integration literature that should be point out here. That is, the different between vertical and horizontal and integration. Whereas the former refers to the process of deepening integration by addressing internal concerns, the latter refers to widening integration by expanding membership. Theoretically, the two can proceed simultaneously. However, due to limitations in resources and the veto power held by member states, the two processes often proceed in turn. Thus, when internal reforms at on top of the agenda, the enlargement process slows down.

This is an important consideration to bear in mind, as research has shown that when enlargement loses its credibility, reforms from candidate states stall.[22] This is precisely one of the reasons why WB elites have been unwilling to undertake the necessary reforms—the ultimate reward of membership is simply too far down the line and unrealistic in the short-term. Much of the literature on the effects of membership relies on rational choice arguments, in that elites are willing to undertake reforms if there is some immediate reward associated with the reform. When reforms are too costly, and the reward of membership is far down the line, politicians are unwilling to bend under EU pressure. Precisely for this reason, research has shown that democracy promotion which offers an enlargement perspective is more effective compared to other forms of promotion.[23]

Turning our attention back to the supply and demand argument, utilizing survey data from the Eurobarometer survey we see that support for enlargement among existing member states has steadily declined over the last decade.[24] Support from EU citizens has declined from 53% in 2004 to 45% in 2018. More importantly, those standing against enlargement have increased from 35 % to 46% for the same time period. In other words, majority of EU citizens today stand against another enlargement, albeit these trends vary from country to country. On the other hand, support for enlargement from the perspective of the WB has also declined, albeit data available for this group of countries is a bit more sporadic and limited. In any case, if we compare level of support in 2014 versus 2018, we see an average decline of 3%, while those standing against have increased by 5%. These are not large fluctuations, but when we look at these trends for North Macedonia for which time-series data goes farther back, support has declined from 90% in 2007 to 74% in 2018.

North Macedonia has also become the emblematic case in illustrating the effects of enlargement fatigue. Up till 2005 North Macedonia was the posterchild for the region. The country had overcome the potential for large-scale violence between the majority Macedonian population and the Albanian communities through the 2001 Ohrid Agreement, ethnic reconciliation was arguably heading in the right direction, reforms were slowly moving the country closers toward European integration, and in 2005 the European Commission granted the country candidate status, thus paving the way for eventual accession. Yet three years later, when Greece vetoed the country’s bid for NATO membership due to the name dispute between the two, the Nikola Gruevski government at the time used the rejection to play into Macedonian claims of historical grievances.[25] From 2008 until Gruevski’s government was forced to step down in 2016 following a series of scandals, inter-ethnic relations between Macedonians and Albanians had gotten sour and democracy had steadily deteriorated until the country’s levels of democracy were near the bottom compared to other WB states. There are now hopes that democracy will get a kickstart after 2018 Prespa Agreement which settled the country’s name dispute with Greece. What North Macedonia’s experience shows, however, is that without a credibility perspective for EU membership, the region is prone to authoritarian reversals.

Despite this important and positive role played by the EU in the region, there are claims to the contrary. One of such arguments suggests that the EU has done little to promote democracy. Rather, what it has promoted is stabilitocracy, that is, promoting regimes that provide political stability at the expense of democracy.[26] While there is nothing novel in the argument that Western powers promote stability at the expense of democracy, with the Cold War period providing numerous examples were the US helped stabilize authoritarian regimes as long as they aligned with the West, promoting such policies in the WB is rather counterintuitive considering the region’s drive toward EU membership. Nevertheless, the stabilitocracy argument does forces us to question the integration process in determining whether it can promote democracy in places like the WB.

Another way through which we can analyze the effects of integration is by understanding the tools the EU utilizes as part of the enlargement process. In this way, we can develop a better understating of theoretical linkages and expected outcomes. The framework though which the accession process is judged and measures is based on what has come to be known as the Copenhagen Criteria. This list of accession criteria emerged as a result of CEE’s desire to join the EU following the collapse of communism in the early 1990s. The list effectively consists of three categories: political, economic, and legal. In the political camp reside the necessity for institutions guaranteeing democracy, rule of law, human rights, and protection of minorities; the economic camp consists of the need to establish a functioning market economy capable of competing in the common market; and the legal camp consisting of the institutional and administrative capacity to implement the acquis. While this list of criteria may at first sight appear specific enough, it is in fact vaguely broad.

For instance, by what measure do we evaluate institutions of democracy, human and minority rights? When are we certain that an economic system has developed the capacity to compete within the common market? And how do we evaluate administrative capacity? The vagueness of the criteria has led to criticisms against the EU under the accusation of ‘moving the goal post’. That is, candidate countries fulfill a certain benchmark, only to be told that there is more work to be done, hence the EU moving the goal post further down the line. It is the dynamics of this framework, however, which gives the EU the leverage to drive reforms forward. As part of this framework, the EU produces an Annual Report which outlines the progress each candidate has made in fulfilling the Copenhagen Criteria. For candidate states the report serves as an objective measure of political progress in the country, which governing and opposition parties utilize to their advantage. Thus, when the report highlights positive progress, governing parties pull out these positives to highlight their successful reforms in getting the country closer toward full membership. Meanwhile, opposition parties pull out the negatives and blame governments for their failure.

Bearing in mind the popular support for integration in the WB, the reports therefore become a powerful tool in forcing governments to address the shortcomings of their reforms. Overall, however, the integration process is an executive focused process. There is little room for mass participation beyond the role of civil society in bringing forward government abuses, while the opposition and parliament are largely removed from the process as it is the government which negotiates directly with the EU. Grabbe has even argued that by marginalizing national legislatures, the EU is exporting its own democratic deficit.[27] For this reason, the process is criticized for being elite focused, and questions are raised as to whether such a process can lead to the necessary attitudinal shift within the masses that we associate with liberal democratic values. Indeed, the accession criteria constitute of institutional measures of democracy, thus leaving aside the other two components of a consolidate system—the behavioral and attitudinal aspects.

The EU, however, has learned from its mistakes and has refined the enlargement process. Following Bulgaria’s and Romania’s accession, the EU realized that rule of law and democratic standards in the two countries did not follow the trajectory that was expected from their membership in the Union. As a result, the EU redesigned its accession process, with new candidates required to first deal with ‘Judiciary and fundamental rights’ and ‘Justice, freedom and security’, Articles 23 and 24 of the Annual Reports respectively. The idea behind this change was to encourage behavioral compliance with rule of law very early on in the process, thus ensuring longer term compliance with democratic norms.

The recent decision by the European Council to offer Albania and North Macedonia the green light to commence accession negotiation is a sign of hope that enlargement is back on. From a formal perspective, the WB is now closer to the EU. However, formal progress in the integration process does not seem to be associated with democratic progress. In a recent study, Richter and Wunsch ask why are we witnessing gradual improvements in formal compliance with membership criteria in the WB, while at the same time we witness stagnating, if not declining, democratic performance.[28] According to Richter and Wunsch, the integration process has helped set in place a series of mechanisms for state capture by legitimizing corrupt elites for formal progress in the accession process while silencing domestic opponents through the top-down nature of the accession process. In other words, not only in the integration process failing to deliver democratic progress, but under certain conditions it may even prove counterproductive. The integration progress may even disguise domestic problems with democracy by shifting focus on the accession criteria and accession process. As Elbasani and Šabić have argued, “[f]ormal compliance…often hides more than reveals regarding the façade nature of EU-led transfers.”[29]

Conclusion

The democracy promotion literature has come a long way since international actors began promoting it in earnest after the collapse of communism. The body of literature that was once primarily descriptive or correlative has evolved to include more causative assessments. The evolution of the literature was also made possible due to the growth of promotion activities from numerous international actors. This has broadened the empirical scope to allow for comparative research designs and the development of more generalizable findings. Actors themselves have been able to learn from their experience in order to formulate more effective promotion policies. Perhaps not all aspects of who, what, how, why and effects have been answered. Yet the democracy promotion literature today does represent a more theoretically coherent research program than two decades ago.

WB elites, however, appears to have resisted EU pressures for democratization. They even appear able to manipulate the process to their benefit. Meanwhile, European integration is often portrayed to the masses in misleading ways such that EU membership will serve as a panacea to their country’s problems. As a result, domestic politics is perceived as intractable, while the EU and other foreign actors as the saviors. Democracy is therefore misconceived as simply a system of rules in which smarter institutional designs from the West will able to overcome problems of corruption, state captures, accountability, transparency, and representation. However, democracy is built more on the belief that collective differences should be addressed through democratic means, rather than smart institutional designs which prevent corrupt politicians from using public office for personal gains.

As the EU attempts to refine its enlargement process by placing preconditions for the commencements of negotiations, such as the case of Albania, or by commencing negotiations with the Articles 23 and 24, such changes simply lengthen the process with the hope that early reforms will become embedded in larger society. It remains to be seen, however, as to what the European future of the WB holds. While the enlargement perspective has regained credibility, the recent history of CEE has shown us that membership is not a panacea. Deeper societal problems are unlikely to find recourse through European integration. While the European future of most WB states is unquestionable at the moment, a stagnated enlargement process could slow reforms even further and provide encroachment opportunities for regional powers such as Russia.

It is worth concluding this article by briefly bringing in the domestic context. While democracy promoters have found innovative ways to achieve their desired objectives, authoritarian rulers have also learned from their predecessors. Thus, while today’s democracy promotion policies may be more coherent, they face a more daunting and constraining domestic environment. This is evident in the fading away of the democratic zeitgeist that dominated the 1990s and the rise of authoritarian learning as anti-democratic elites have learned to share practices, know-hows, technologies and policies in ensuring they remain in power. WB elites and societies are no exception in this respect.

Acknowledgment:

Part of this manuscript may later appear in a college textbook edited by the author.

ELTION MEKA is a Researcher at the University of New York Tirana.

References:

Bieber, Florian. The rise of authoritarianism in the Western Balkans. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020.

Bridoux, Jeff, and Milja Kurki. “Cosmetic agreements and the cracks beneath: ideological convergences and divergences in US and EU democracy promotion in civil society.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 28, no. 1 (2015): 55-74.

Cianetti, L., Dawson J. and Hanley, S. “Rethinking “democratic backsliding” in Central and Eastern Europe–looking beyond Hungary and Poland.” East European Politics 34, no.3 (2018): 243-256.

Elbasani, Arolda, and Senada Šelo Šabić. “Rule of law, corruption and democratic accountability in the course of EU enlargement.” Journal of European Public Policy 25, no. 9 (2018): 1317-1335.

Epstein, R.A., and U. Sedelmeier. Beyond conditionality: international institutions in postcommunist Europe after enlargement. Journal of European Public Policy 15, no. 6 (2008): 795–805.

Ethier, Diane. “Is democracy promotion effective? Comparing conditionality and incentives.” Democratization 10, no. 1 (2003): 99-120.

European Commission. Standard Eurobarometer 90, December 2018. https://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm, Accessed April 19, 2020.

Grabbe, Heather. How does Europeanization Affect CEE Governance? Conditionality, Diffusion and Diversity.’ Journal of European Public Policy, 8, no. 6 (2001): 1013-31.

Haukenes, Katrine, and Annette Freyberg-Inan. “Enforcing consensus? The hidden bias in EU democracy promotion in Central and Eastern Europe.” Democratization 20, no. 7 (2013): 1268-1296.

Hobson, Christopher, and Milja Kurki. “Introduction The conceptual politics of democracy promotion.” in The conceptual politics of democracy promotion, edited by Christopher Hobson and Milja Kurki. Routledge, 2012.

International Crisis Group, Macedonia: Ten Years After the Conflict, Europe Report N°212 – 11 (August 2011).

Kmezić, M. and Bieber, F. The Crisis of Democracy in the Western Balkans: An Anatomy of Stabilitocracy and the Limits of EU Democracy Promotion. BiEPAG Policy Study, (2017).

Linz, J.J and Alfred Stepan. Toward Consolidated Democracies. Journal of Democracy, 7, no. 2 (1996): 14-33.

Manners, Ian. “Normative power Europe: a contradiction in terms?” JCMS: journal of common market studies 40.2 (2002): 235-58.

Manners, Ian. “The normative ethics of the European Union.” International Affairs 84, no. 1 (2008): 45-60.

Mungiu-Pippidi, Alina. “EU Enlargement and Democracy Progress” in Michael Emerson (ed.) Democratisation in the European Neighbourhood. CEPS Paperback Series. (2005). pg.15-16.

Mungiu-Pippidi, Alina. “EU Accession Is No” End of History”.” Journal of Democracy 18.4 (2007): 8-16.

Norris, P. and Ronald Inglehart. Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism. Cambridge University Press, 2019.

O’Brennan, J. ‘On the slow train to nowhere?’ The European union,’Enlargement Fatigue’ and the Western Balkans. European Foreign Affairs Review. 19 (2014): 221-241.

Offe, Claus, and Pierre Adler. “Capitalism by democratic design? Democratic theory facing the triple transition in East Central Europe.” Social Research (1991): 865-892.

Pridham, Geoffrey. Designing democracy: EU enlargement and regime change in post-communist Europe. Basingstoke, 2005.

Richter, S., and Wunsch, N. Money, power, glory: the linkages between EU conditionality and state capture in the Western Balkans. Journal of European Public Policy, 27, no. 1 (2020): 41-62.

Schimmelfennig, Frank. “How Substantial is Substance-Concluding Reflections on the Study of Substance in EU Democracy Promotion.” Eur. Foreign Aff. Rev. 16 (2011): pp727-734.

Schimmelfennig, Frank, and Hanno Scholtz. “EU democracy promotion in the European neighbourhood: political conditionality, economic development and transnational exchange.” European Union Politics 9, no. 2 (2008): 187-215.

Schmidt, Jessica. “Constructing new environments versus attitude adjustment: contrasting the substance of democracy in UN and EU democracy promotion discourses.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 28, no. 1 (2015): 35-54.

Vachudova, M.A. “Tempered by the EU? Political parties and party systems before and after accession.” Journal of European Public Policy 15, no.6 (2008): 861-79.

Vachudova, M.A. “EU Leverage and National Interests in the Balkans: The Puzzles of Enlargement Ten Years On.” Journal of Common Market Studies 52, no.1 (2014): 122-138.

Wetzel, Anne, and Jan Orbie. “With map and compass on narrow paths and through shallow waters: discovering the substance of EU democracy promotion.” Eur. Foreign Aff. Rev. 16 (2011): 705-725.

Wetzel, Anne, Jan Orbie, and Fabienne Bossuyt. “One of what kind? Comparative perspectives on the substance of EU democracy promotion.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs. 28, no.1 (2015): 21-34.

Whitehead, L. ed. The international dimensions of democratization: Europe and the Americas. Oxford University Press, 1996.

Youngs,

Richard. The European Union and democracy promotion: A critical global

assessment. JHU Press, 2010.

[1] O’Brennan, J. ‘On the slow train to nowhere?’ The European union,’Enlargement Fatigue’ and the Western Balkans. European Foreign Affairs Review. 19 (2014): 221-241.

[2] Bieber, Florian. The rise of authoritarianism in the Western Balkans. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 2020.

[3] Pridham, Geoffrey. Designing democracy: EU enlargement and regime change in post-communist Europe. Basingstoke, 2005.

[4] Whitehead, L. ed. The international dimensions of democratization: Europe and the Americas. Oxford University Press, 1996.

[5] Wetzel, Anne, Jan Orbie, and Fabienne Bossuyt. “One of what kind? Comparative perspectives on the substance of EU democracy promotion.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs. 28, no.1 (2015): 21-34.; Bridoux, Jeff, and Milja Kurki. “Cosmetic agreements and the cracks beneath: ideological convergences and divergences in US and EU democracy promotion in civil society.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 28, no. 1 (2015): 55-74.; Manners, Ian. “The normative ethics of the European Union.” International Affairs 84, no. 1 (2008): 45-60.; Schimmelfennig, Frank, and Hanno Scholtz. “EU democracy promotion in the European neighbourhood: political conditionality, economic development and transnational exchange.” European Union Politics 9, no. 2 (2008): 187-215.; Ethier, Diane. “Is democracy promotion effective? Comparing conditionality and incentives.” Democratization 10, no. 1 (2003): 99-120.

[6] Hobson, Christopher, and Milja Kurki. “Introduction The conceptual politics of democracy promotion.” in The conceptual politics of democracy promotion, edited by Christopher Hobson and Milja Kurki. Routledge, 2012. p3.

[7] Linz, J.J and Alfred Stepan. Toward Consolidated Democracies. Journal of Democracy, 7, no. 2 (1996): 14-33. p14-15.

[8] Norris, P. and Ronald Inglehart. Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism. Cambridge University Press, 2019.

[9] Offe, Claus, and Pierre Adler. “Capitalism by democratic design? Democratic theory facing the triple transition in East Central Europe.” Social Research (1991): 865-892.

[10] Wetzel et al. One of what kind?.

[11] Bridoux and Kurki. Cosmetic agreements and the cracks beneath.

[12] Haukenes, Katrine, and Annette Freyberg-Inan. “Enforcing consensus? The hidden bias in EU democracy promotion in Central and Eastern Europe.” Democratization 20, no. 7 (2013): 1268-1296.

[13] Schimmelfennig, Frank. “How Substantial is Substance-Concluding Reflections on the Study of Substance in EU Democracy Promotion.” Eur. Foreign Aff. Rev. 16 (2011): pp727-734. p730.

[14] Wetzel, Anne, and Jan Orbie. “With map and compass on narrow paths and through shallow waters: discovering the substance of EU democracy promotion.” Eur. Foreign Aff. Rev. 16 (2011): 705-725.; Schmidt, Jessica. “Constructing new environments versus attitude adjustment: contrasting the substance of democracy in UN and EU democracy promotion discourses.” Cambridge Review of International Affairs 28, no. 1 (2015): 35-54.

[15] Youngs, Richard. The European Union and democracy promotion: A critical global assessment. JHU Press, 2010. p1.

[16] Manners, Ian. “Normative power Europe: a contradiction in terms?” JCMS: journal of common market studies 40.2 (2002): 235-58.

[17] Mungiu-Pippidi, Alina. “EU Enlargement and Democracy Progress” in Michael Emerson (ed.) Democratisation in the European Neighbourhood. CEPS Paperback Series. (2005). p15-16.

[18] Epstein, R.A., and U. Sedelmeier. Beyond conditionality: international institutions in postcommunist Europe after enlargement. Journal of European Public Policy 15, no. 6 (2008): 795–805.; Cianetti, L., Dawson J. and Hanley, S. “Rethinking “democratic backsliding” in Central and Eastern Europe–looking beyond Hungary and Poland.” East European Politics 34, no.3 (2018): 243-256.

[19] Vachudova, M.A. “Tempered by the EU? Political parties and party systems before and after accession.” Journal of European Public Policy 15, no.6 (2008): 861-79. p862.

[20] Vachudova, M.A. “EU Leverage and National Interests in the Balkans: The Puzzles of Enlargement Ten Years On.” Journal of Common Market Studies 52, no.1 (2014): 122-138.

[21] Mungiu-Pippidi, Alina. “EU Accession Is No” End of History”.” Journal of Democracy 18.4 (2007): 8-16. p16.

[22] O’Brennan. On the slow train to nowhere?.

[23] Schimmelfennig and Scholtz. EU democracy promotion in the European neighbourhood.

[24] European Commission. Standard Eurobarometer 90, December 2018. https://ec.europa.eu/commfrontoffice/publicopinion/index.cfm, Accessed April 19, 2020.

[25] International Crisis Group, Macedonia: Ten Years After the Conflict, Europe Report N°212 – 11 (August 2011).

[26] Kmezić, M. and Bieber, F. The Crisis of Democracy in the Western Balkans: An Anatomy of Stabilitocracy and the Limits of EU Democracy Promotion. BiEPAG Policy Study, (2017).

[27] Grabbe, Heather. How does Europeanization Affect CEE Governance? Conditionality, Diffusion and Diversity.’ Journal of European Public Policy, 8, no. 6 (2001): 1013-31. p1017.

[28] Richter, S., and Wunsch, N. Money, power, glory: the linkages between EU conditionality and state capture in the Western Balkans. Journal of European Public Policy, 27, no. 1 (2020): 41-62.

[29] Elbasani, Arolda, and Senada Šelo Šabić. “Rule of law, corruption and democratic accountability in the course of EU enlargement.” Journal of European Public Policy 25, no. 9 (2018): 1317-1335. p16.