ENIKA ABAZI

Enlargement in pandemic times

The COVID-19 pandemic crisis is likely to accelerate geopolitical changes at all levels, and the EU enlargement is going on. On March 25, the Council of the European Union gave the green light to the opening of the access negotiations for Albania after four consecutive refusals. The decision was taken by the EU Minister for Foreign Affairs at a meeting by videoconference. Although long-awaited, the decision was a surprise in the midst of a serious global pandemic crisis, while its management is calling into question the raison d’être of the European project for its citizens, and exposing its essential weakness on forging solidarity and coordinating a common action among member states.

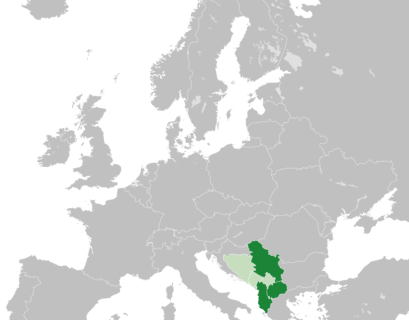

In view of the past, this enlargement is not business as usual. European officials in a hurry explained that the decision was strategic, a “loud and clear message not only to the two countries, but to the Western Balkans as a whole,” confirming the geostrategic “importance of the Western Balkans” and “the European Union’s geostrategic interest” (European Commission 2020, 25 March).[1] Yet, the decision is only the first step in re-engaging in the region more actively. This sounds as an old cliché. In fact, since early 2016, with the acceleration of the refugee crisis, and pronounced ‘fatigue’ of EU-enlargement, a window of opportunity has been opened to China, Russia and Turkey in the Western Balkans to advance their interests, making evident a ‘return’ of great power politics in the Balkans.[2] The geopolitical importance of the Western Balkans Six was recognized explicitly by the EU recent strategy of the European Commission[3], which feared that the Balkans can easily “become one of the chessboards where the big power game can be played”.[4]

Despite the concern, EU has failed to provide a comprehensive common strategy towards the region, which is most uncomfortably felt in the frequent definition/redefinition of the region from Balkans in the broad sense, to “de-balkanize” the South-East Europe, and then to Western Balkans which designates all the countries currently awaiting accession to the EU in the region, to the last label Western Balkans Six representing the countries left outside the Union. All regional names coexisting without having any real ascendancy in different EU documents and discourses.[5] Ironically, they hide different political projects that in the past different Member States gatekeepers have labelled to mark their intentions and interests[6],[7]. The Confusion about the definition of the region, reveals both EU’s interest in the region and its ambiguity on how to pursue it. The conflict of interests between EU member states has turned around enlargement or containment, involving contentious and incompatible positions[8]. In this sense, the last enlargement decision is a long overdue step, which offers no surprises.

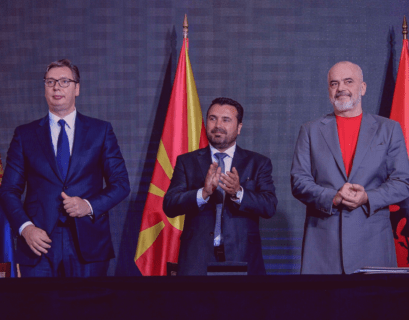

In view of the present, the COVID-19 crisis and its handling, more than anything else, is highlighting and reinforcing the basic features of new geopolitics in all levels, Western Balkans are no exception. The new rising powers are inserting themselves in the region in place of the EU by assisting distressed national governments with much needed humanitarian aid. Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić was the first to prize China’s aid while disparaging the European approach on the same remark. For him: “European solidarity does not exist… that was a fairy tale on paper. The only country that can help us in this hard situation is the People’s Republic of China. To the rest of them, thanks for nothing.”[9]. At the same time, Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama, declared that Albania’s plan C “if the world is upside down” is Turkey, which is committed to meeting the critical health needs of the country[10]. Next in the line of thanksgivings was President of Montenegro Milo Đukanović, showing gratitude to the President of Turkey, Erdogan for the health aid[11]. Russia, too, looks set to help the Balkan states. Like China and Turkey it is stepping in to replace the faltering EU, flying in among other aids doctors and equipment to Serbia by 11 military planes.[12]

In the view of the future, EU enlargement to which European leaders tether their hopes for preserving the existing balance of interests in the region, is undermined by the fact that politics nowadays is exposed to a severe anarchy of the global order. From a realist point of view, this is a period in which the uncertain workings of the multipolar balancing process may bring important geopolitical shifts in world leadership and distribution of the zones of influences. The situation looks even more complex and brews with instability, considering that the reconfiguration of power is in the making and the redistribution of power may have a bearing upon states’ choices of allies. In these circumstances, EU is ambiguous about moving towards a deep mode of integration and developing mechanisms to anticipate and alleviate negative consequences of geopolitical developments. It is not the first time that the politics of enlargement, old and new, find EU squeezed in a twisted dilemma of either opening negotiation before standards or standards before negotiations. Keeping standards first would mean christening countries fatigue, haunted by the Copenhagen criteria, add-ons, Europeanization and ambiguity in the definition and redefinition of a region which have variated since the 1990s according to pragmatic political criteria and recently by the COVID-19 crisis. Favoring negotiations seems to be a precondition to keep WB6 from turning their backs on Europe and moving towards authoritarian powers that do not currently uphold EU values. Until now, both sides seem falling for the prisoner’s dilemma, the notorious paradox in game theory in which two parties act out of individual self-interests and both lose out in the process.

The rise of the others[13] is real and EU knew

At least since 2014, with the annexation of Crimea, in Europe the order of things has changed with the return of Russian rivalry and competition to Europe. With the immigrant crisis accelerating the same year, Turkey also took the opportunity to gain leverage over the EU because it holds some of the keys to managing the refugee flows. The pressure becomes more relevant particularly in areas where interests and influence overlap. One such area is the Western Balkans, where historically Russia and Turkey are longtime actors with their own interests and agendas, that have been reasserting their interests in the region for some time. Unlike Russia and Turkey, China’s plans for the region are more ambitious. China is claiming a global leadership role by increasing investment in the types of assets that established EU as a normative power and set US leadership and authority for the second part of the last century, like foreign aid, humanitarian interventions, contributing to UN peacekeeping forces, and joining international initiatives to address global problems such as terrorism, piracy, nuclear proliferation[14] and recently COVID-19 crisis. In the framework of integrating the 16+1 initiative into the platform of the Belt and Road Initiative, China is working full steam on institutionalizing cooperation with each of the Balkan countries. The other issue raising concerns is the question of whether Russian, Turkish and Chinese activities in the region will lead them to buy influence at the political level, which may challenge seriously the EU investment and maybe its cohesion. In fact, the other powers have been quietly gaining ground for years in the WB6. More details will be provided later taking the case of Albania.

To simplify a complicated story, it helps to recall what was stated only two years ago by one of the leaders of the WB6 countries. In December 2017, during a conference organized by Friends of Europe, Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama states in his quality of Albania’s gatekeeper: “Russia and China have many things to offer. Russia can give you power energy for the rest of your life if you give up the rule of law. It is not quite uninteresting… China has the luxury to plan for the next 100 years. I would not say they have nothing to offer. And then there is also radical Islam. In our region, we are multiethnic, multi-religious. If the EU will not run to catch us, believe me, many multi-problems can restart and then it will be much more costly to marry with us later”[15]. One can sense that political doubletalk is deliberate. The speech is not so much intended to deceive as to use the created geopolitical leverage to haste decisions that would favor his political pledge to get EU accession for Albania. EU is in a certain hazel coming from a believed return of the Cold War in the Balkans, while Rama hopes to succeed by tapping into it[16]. This speech can be highly challenging, especially when the Russians, Chinese and Turks in search of zones of influence are investing in the Western Balkans and using Coronavirus diplomacy for either geopolitical gain or commercial profit. Rama got into EU insecurities and he sounded credible in the promise that the country will comply with EU requirement, and the pledge was won despite the odds two years later. When one presents a situation as an opportunity, not a problem, and pledges to tell it as it is, it fits a double function, wobble the situation and control it by every action available. We may observe an effort to turn geopolitical challenges into political benefits. Everything looked like standard staging, with a leader in distress and a low moan of despair. Yet, Rama seems to be savvy on the situation.

Soon after this speech, the efforts to introduce a hasty strategy for the WB6 to mild out Russia, China, and Turkey’s influences into the WB6, did gain ground[17]. The geopolitical breeze was already blowing in favor of those who wanted the opening of the negotiations with Albania and North Macedonia. The novel coronavirus has turned it into a hurricane. Grumbles about restrained enlargement policy beloved by the skeptics have been growing since. “Flexibility” has been the preferred euphemism for a concerted effort to water down the previous cautious attitude. The geostrategic importance of the region in combination with the need to support pro-European leaders has however weakened the strength of political conditionality and it has an explanation. During the last immigration crisis, the threat of uncontrolled flows coming from the East made EU highly dependent on the cooperation with Western Balkan on issues of security and control of boarders, and consequently security overshadowed other concerns such as corruption, rule of law or freedom of media in the countries of the region. The situation as it is observed and reported in the last strategic document of the European Commission[18] reveals a democratic backslide and stagnation in the Western Balkans Six countries. Albania is not mentioned explicitly but is part of the WB6. Now the gravity of the COVID-19 crisis offers a nihilistic twist to previous positions of enlargement skeptics like France, Denmark, and the Netherlands. Sometimes a crisis is so harsh that previous behavior becomes irrelevant and the judgment blurs.

The approval of the opening of the accession talks with Albania this March, was welcomed yet it did not yield any particular enthusiasm in the country despite the government’s efforts to claim victory. The effort quickly was eclipsed by the Coronavirus crisis, distracted responses of the EU on the matter and the fact that the adopted Council decision placed further preconditions on Albania, notably related to electoral reform, the rule of law, and fighting corruption. However, even before that, EU enlargement fatigue has left the place to the weariness of patience of the public. In Albania, which is considered the most Europe-loving country in the continent, the support to European integration has slowly but steadily decreased. Based on longitudinal data of annual surveys by the Albanian Institute of International Studies (AIIS) since 2006, the support of Albanian public to EU integration has been almost unanimous, reaching in 2008 up to 95%. [19]After 2010, the support fluctuated between 85% and nearly 77% before the candidate status was granted in June 2014.[20]

In the case of Albania, the risk of switching preferences is high as economic linkages with the EU remain below the potential, which creates high political costs to pro-European elites in Albania. In 2016, the enterprises from the EU countries covered approximately 2.5 % of total active enterprises in the country. Focused mainly on the service sector rather than high value-added manufacturing industry or agriculture (809 enterprises from the total of 3944 enterprises) and the majority (3024) being small in size, employing only 1 to 4 people[21], their input on FDI hardly addressed the country’s economic structural problems and lack of connectivity with the region and Europe. Even trade between EU and Albania, is still below the potential, with Albania representing only 0.1 percent of its total trade. As the costs of reforms are upfront, the low expectation about the likelihood of full EU membership may influence an applicant’s calculation of gains in different directions. A delay of the EU membership is slowing the reform process or even undo certain reforms[22] and driving illegal Albanian immigration into Europe, which in Albanian social networks is named as a “free movement of people from below”. In other words, the government is more willing to bear the political costs of regulatory reforms if the EU credibly commits itself to enlargement. If this commitment turns out to be wavering, it may turn elsewhere for help.

Albanian EU membership perspective seems to have encouraged China to start working full steam on institutionalizing cooperation in the framework of 17+1 initiative, which is now integrated into its platform of Belt and Road Initiative. Chinese capital and infrastructure projects represent a tempting market proposition for Albania and a potential platform for China to leverage its growing economic and political influence in Europe[23]. In the last years, China has become the second Albanian trading partner with 7.1 percent of the total trade, leaving behind old-time partners like Greece and Turkey, though well behind the EU trade (67.5 %).[24] Still, the trend is very striking, as no one could account for Albanian export growth to China of over 6000 percent[25] [26]. China’s ambition to control Albanian strategic sectors and extractive industries, such as petroleum and chromium, road, air, and sea infrastructures, as well as agriculture, seems growing in pace. Only in 2016 China has invested into at least five main projects. In March 2016, China’s Geo-Jade Petroleum bought for a price of 384.6 million euros Canadian Bankers Petroleum oil exploration and production rights. An important deal that accounted for nearly 5 percent of Albanian nominal GDP[27]. On April 2016, China Everbright and Friedmann Pacific Asset Management took hold of Tirana International Airport. The investment is promising as Tirana airport is one of the fastest-growing in Europe, with annual passenger rates rising from 600,000 in 2005 to two million in 2015.[28]

China’s leverage seems to be a charming “soft power” offensive, mostly based on economic, infrastructure and trade penetration leading to dependency linkages. The so-called “Chinese wisdom” or “Chinese approach” comes as an alternative to Western democracy, “a new option for other countries” to solve their development problems[29]. Chinese approach does not engage in the domestic affairs of the country and gives little consideration to the nature of the regime and government. It favors economic and trade interests while showing political pragmatism. China pursues investments and is often able to come in as an investment alternative in a country in desperate need of foreign capital for its modernization.

After so many years of EU prompted reforms, Albania is still many years behind its neighbors. In 2016, Albania’s GDP per capita (at purchasing power standards) is at 13 percent of the EU-28 average[30]. Moreover, after late 2008, due to the global financial crisis Albania has also experienced a strong reduction of FDI and other capital inflows[31]. In these conditions, Chinese investments promise development, while the EU adjustment funds for development and structural and economic change would come only if Albania becomes full EU member. Ironically, Albania cannot be member without having transformed its economy. In this respect, China’s investments are both an opportunity and a challenge. Being state-backed or state-owned, most of Chinese companies adopt streamlined procurement procedures that facilitate their penetration in the Albanian market and the money they bring is tempting and potentially promising. Yet, the infrastructure projects and lending agreements burden the government with large debt obligations. Despite promises and perspectives, it remains to be seen if these investments will bring serious technological development and not just adjustment to increase profits, or an increase in environmental pollution and no increase in employment as most Chinese companies import their own labor from China and serve as proxies for the Chinese government.[32]

For Russia “in addition to economic opportunities, Albania has a significant political potential in the area. Albania has the fourth largest population in the Balkans, which tends to increase. The ‘Albanian factor’ has to be reckoned with. All this, along with nostalgic memories of the former strong friendship and the development of economic relations could yield good results, given a thoughtful approach to modern Albania”[33]. However, Albania has been strongly geared to the West, which does not encourage the development of strong linkages to Russia. The share of Russia in Albanian total trade is about 1.1 percent[34]. The EU-type economic sanctions that Albania imposed on Russia and counter-measures prohibiting imports of Albanian agricultural products to Russia, explains partly the low level of trade exchanges. Nevertheless, Russia has waged a robust campaign to increase its influence in Albania as elsewhere, which includes using cyberspace, funding, and disinformation to influence political parties and voting constituencies. The idea is that Moscow is trying to sow confusion and distrust and help advance its interests in the country without having to resort to conflict.[35] Sputnik based in Serbia since 2014, now with an opening section in Tirana, provides pretty much all defense and security news to mainstream media.[36] However, some of Russia’s growing sway is unseen by the public and difficult to be witnessed.

For the first time, in the Albanian media it is insinuated that Russia could have influenced last parliamentary elections of 2017. According to the investigative magazine Mother Jones, the hired an offshore company by the Democratic Party was supposedly controlled by Russians.[37] The assumption is that a victory of the DP would have blocked the judicial reform, thus inevitably chilling Albanian relations to the EU, which ultimately would have helped Russian plans to destabilize the entire region. Much of the story did not make sense for many Albanians and was considered a piece of fake news. Yet it has become clear that Russia will venture to seize every opportunity to pursue its grand design of rewriting the Balkan order in Russian characters.

In the 2010s, the rapid economic growth enabled Turkey to strengthen its linkages with Albania, which are now more ambitious and assertive. Ankara has been always a balancing actor in the Balkans preventing the creation of a Serb-Orthodox axis that may block Turkey’s way to Europe placing Russia back in an advantageous position and jeopardizing Albanian security interests. These calculations pushed Turkey to recognize the independence of Kosovo, even though risky parallels could be drawn with the Kurdish question[38]. Turkish security leverage on the Albanian security field is tangled recently as Turkey is aligning with Russia on different foreign policy, security and economic issues, while Albania is looking to advance with EU membership and is following EU and NATO policies regarding Russia.

Turkey is the third commercial partner of Albania[39] and an important source of foreign direct investments from several public and private enterprises in strategic sectors such as communication, infrastructure, and banking. In 2007, Albania received 42.2 percent of overall outward FDI from Turkey through the partial privatization of public assets. At the end of 2017, Turkish total direct investments in Albania reached 2.7 billion euros[40]. Nevertheless, Turkish FDI outflows are still insignificant compared to the investments from EU28 and individual member states[41]. Turkey is the sixth partner in terms of investments. Although the number of Turkish enterprises is increasing, they still represent 7.7 percent of total foreign and joint enterprises in Albania compared to 71.4% for the EU.[42] The volume of total trade reaching 423 million euros, which represent only 5.9 percent of all Albanian trade, leaving Turkey behind the EU28 (66.2%) and China (6.5%).[43]

Turkey proposes an alternative development model to Albania. The Ottoman Empire model of millet coexistence is proposed as a “complementary” rather than “competitive” to the European Union integration policy.[44] Following this course, Turkey has launched various Balkan initiatives for participation in newly established structures.[45] It established a visa-free regime with Albania and signed a free-trade agreement, as part of a Turkish style Schengen and economic community area in the Western Balkans. In fact, the idea is similar to EU Neighbourhood Policy. Up till now, many observers consider that Turkish policies show how the Europeanisation discourse is used as an instrument to establish it as primus inter pares. Without the European anchor Turkish leaders would not be in a position to promote Turkey as an example and call on Albania to rally around it.[46]

Turkey is extensively investing in the Albanian societal field. TIKA[47] projects, Yunus Emre Cultural Centers, Turkish education institutions and Turkish soap operas have extensively contributed to a kind of re-consideration of the Ottoman period and exposed and popularized Turkish culture and contemporary way of life. They have promoted the image of Turks as a modern people countering the traditional awkward image previously widespread in the country through history textbooks, which represented the Ottoman yoke as ruthless and responsible of country’s backwardness and the forceful conversion of Albanians from Christianity to Islam. Ironically, while for many foreigners the construction of a mega-mosque in Tirana, financed by Diyanet[48], is a fact that corrupts the Western choice of Albanians, its address is on George W. Bush Street.

In lieu of conclusions

Mainly because of the close linkages developed with the Western Balkans Six countries, until recently the EU has so far not perceived the “rise of the rest”[49] as a danger to its own interests in the WB6 counties. The record of EU investments in all the countries of WB6 is impressive. In the case of Albania, as a matter of fact, at the end of 2016, the EU remains, the first trading partner of Albania with 62 percent of imports and 77 percent of exports, the key FDI stock contributor with 59.3 percent of the total[50] and the main investor in foreign and joint ventures with 70 percent of the total number.[51] The EU is the largest provider of financial assistance with €1.24 billion in EU pre-accession funds, €359 million provided in European Investment Bank loans since 1999, leveraging investments estimated of €1.2 billion[52]. The EU also stands as a leading donor in relation to the promotion of human rights by financing several projects in the framework of the European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights with a contribution of €86.5 million[53]. Visa liberalization regime for Albanian citizens in the Schengen area (2010) fostered social and cultural linkages. The exchanges under Erasmus+ and the support to civil society brought students, journalists, young politicians, trade union leaders and teachers closer to share ideas and projects with their European partners. In only one year, 2015-2016, 3660 students, academics and youth from Albania visited different EU academic institutions.[54] The participation in the EU Research and Innovation program created opportunities for Albanian academia to be part on projects for advancing science, industrial leadership and tackling societal challenges. Albania has participated on the FP7 (2017-2013) with 245 projects providing for €2.361.838[55]. Because of that, “Albania, a country with a relatively small volume of scientific publications has high-quality publications relative to the rest of the region. With 4.03 cites per document, it is the leader in the Western Balkans in the 2003–2010”[56]. Moreover, the EU provides funds for a wide range of projects and programs covering areas such as regional and urban development, employment and social inclusion, agriculture and rural development, consolidation of the justice system and fighting and supporting the formulation, coordination and implementation of anti-corruption policies (Euralius IV). These linkages increased the number of domestic actors with a political, economic, or professional stake in adhering to European norms that maintain the high support for EU membership. Moreover, the EU linkage is desirable, and not simply a rational calculation of possible benefits and an agency of problem-solving. Above all, it is a signifier of identity.[57] The well-known Albanian writer Ismail Kadare marks the importance by emphasizing that Albanian “sensational rebellion against the Ottoman state avowed a new idea and a new ideal: the division from the East and the alliance with the West.”[58]

However, the region and Albania remain among the poorest in Europe. And for more than a decade, the EU proposed model seems to be in competition with a “civilization challenger” like China[59], whose ultimate aim is to make Eurasia, including Western Balkans an economic and trading area to rival the transatlantic one[60]; a “spoiler power” like Russia that is trying to derail Balkan countries from the influences of Western institutions by exploit its favorable position with different communities in the region[61]; a growing “regional power” like Turkey that is significantly stronger than its Balkan neighbors and is looking to translate this strength into influence.[62] The challenges to the EU project in the Western Balkans are even bigger, at least in the short term, considering Beijing, Moscow, and Ankara’s tacit agreement to sidestep any suggestion of undermining each other’s initiatives with competing projects.

The belief that these geopolitical challenges can be solved by offering an ambiguous European enlargement proposal is magical thinking. This experiment has run its course long ago, because EU’s recent move is not a temporary rupture in an otherwise stable equilibrium. A more fragmented region is coming into being that in some ways maybe more flexible and open to opportunities. Especially now that autocracies promote vigorously alternative economic and “civilizational” models, using all means at their disposal, from investments on soft power to coercion, aiming to stabilize their neighborhoods and/or challenge Western hegemony.

ENIKA ABAZI is the Director of Peace Research Institute, Paris and lecturer, University of Lille. She has a Ph.D. from Bilkent University.

Bibliography

Abazi, Enika. 2008a. “Albania in Europe: Perspectives and Challenges.” Eurasian Files (Avrasya Dosyasi): International Relations and Strategic Studies 14 (1):229-252, https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01142295.

Abazi, Enika. 2008b. “A New Power Play in the Balkans: Kosovo’s Independence.” Insight Turkey 10 (2):67-80.

Abazi, Enika, and Albert Doja. 2017. “The past in the present: time and narrative of Balkan wars in media industry and international politics.” Third World Quarterly 38 (4):1012-1042. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2016.1191345.

Abazi, Enika, Albert Rakipi, and Dorarta Hyseni. 2008. Albania and European Union: Rethinking EU Integration, http://www.houseofeurope.org/pdf/Perceptions_2008.pdf. Tirana: AIIS.

AIIS. 2014. The European Perspective of Albania: Perceptions and Realities. Tirana: AIIS press.

Bartlett, Will, and Ivana Prica. 2012. The Variable Impact of the Global Economic Crisis in South East Europe, LSEE Papers. London: LSE European Institute.

Bastian, Jens. 2017. The potential for growth through Chinese infrastructure investments in Central and South-Eastern Europe along the “Balkan Silk Road”, www.ebrd.com/documents/policy/the-balkan-silk-road.pdf, European Bank for Construction and Development. London.

Cappello, John. 2017, 05 April. “Russia Escalates Disinformation Campaign in Western Balkans.” www.defenddemocracy.org/media-hit/john-cappello-russia-escalates-disinformation-campaign-in-western-balkans/.

Cappello, John. 2017, 13 October. Russia Ramps Up Media and Military Influence in Balkans. Washington: Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD): http://www.defenddemocracy.org/media-hit/john-cappello-russia-ramps-up-media-and-military-influence-in-balkans/.

Cattaruzza, Amaël. 2008. “L’affirmation de l’Union européenne dans les Balkans. Vers une politique d’intégration régionale… mais de quelle région?” Strates: Matériaux pour la Recherche en Sciences Sociales 15 (http://journals.openedition.org/strates/6688).

Corn, David, Hannah Levintova, and Dan Friedman. 6 March 2018. “How a Russian-Linked Shell Company Hired An Ex-Trump Aide to Boost Albania’s Right-Wing Party in DC.” Mother Jones. https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2018/03/how-a-russian-linked-shell-company-hired-an-ex-trump-aide-to-boost-albanias-right-wing-party-in-dc/.

Davutoglu, Ahmet. 2008. “Turkey’s Foreign Policy Vision: An Assessment of 2008.” Insight Turkey 10 (1):77-96.

de Borja Lasheras, Francisco, Vessela Tcherneva, and Fredrik Wesslau. 2016. Return to instability: How migration and great power politics threaten the Western Balkans. London: European Council on Foreign Relations.

Demirtas, Birgul. 2015. “Turkish Foreign Policy towards the Balkans: A Europeanized Foreign Policy in a De-europeanized National Context?” Journal of Balkan and Near Eastern Studies 17 (2):123-140.

Dita, Gazeta. 2020, 22 March. Plani C dhe Plani D. http://www.gazetadita.al/vetem-rama-nderron-qendrim-nese-bota-permbyset-kemi-turqine/.

Đukanović, Milo. 2020, 8 April. edited by Twiter: https://twitter.com/i/status/1247854322358128640.

Ehrhart, Hans-Georg. 1999. “Prevention and Regional Security: The Royaumont Process and the Stabilization of South-Eastern Europe.” In OSCE Yearbook 1998, 327-346. Baden-Baden: University of Hamburg, Institute for Peace Research and Security Policy.

Estrin, Saul, and Milica Uvalic. 2016. “Foreign Direct Investment in the Western Balkans: What Role Has it Played During Transition?” Comparative Economic Studies 58 (3):455–483.

EU Data. 2018. Albania On Its European Path. Brussels.

EURACTIV. 2020, 30 March. EU announces Covid-19 help for Balkans eastern neighbours after criticism. https://www.euractiv.com/section/eastern-europe/news/eu-announces-covid-19-help-for-balkans-eastern-neighbours-after-criticism/.

European Commission. 2018a. “A credible enlargement perspective for and enhanced EU engagement with the Western Balkans.” https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/communication-credible-enlargement-perspective-western-balkans_en.pdf.

European Commission. 2020, 25 March. Commission welcomes the green light to opening of accession talks with Albania and North Macedonia. Brussels: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_20_519.

European Commission, IPA II. 2018b. Revised Indicative Strategy Paper For Albania (2014-2020). Brussels.

European Parliament. 30 April 1998. Report on the role of the Union in the world: Implementation of the common foreign and security policy for 1997. edited by Security and Defense Policy Committee on Foreign Affairs. Brussels.

Gadis, Karolos. 2018, 28 January. “Turkey’s destabilizing role in the Balkans and South East Mediterranean area.” Hellenic News, https://hellenicnews.com/turkeys-destabilizing-role-balkans-south-east-mediterranean-area/.

IMF. 2017. “Country Report Albania: Selected Issues.” 17/374

INSTAT. 2017. Foreign Enterprises in Albania 2014-2016 Tirana: http://www.instat.gov.al/media/3663/foreign-enterprises-in-albania.pdf.

Janjevic, Darko. 2017. “Erdogan wants Balkans as ‘leverage’ on Europe.” Deutsche Welle, (www.dw.com/en/erdogan-wants-balkans-as-leverage-on-europe-expert/a-38009794).

Jinping, Xi 2017. Report at 19th CPC National Congress. Beijing: Xinhua: www.xinhuanet.com/english/download/Xi_Jinping’s_report_at_19th_CPC_National_Congress.pdf.

Kadare, Ismail. 2006. Identiteti Europian i Shqiptarëve: sprovë [Albanian European Identity]. Tirana: Onufri.

Kurbatskiy, Vladislav 2012. Albania and Russia Rapprochement. Moscow: http://russiancouncil.ru/en/analytics-and-comments/analytics/albania-and-russia-rapprochement/: RIAC.

Mattli, Walter, and Thomas Plümper. 2004. “The Internal Value of External Options: How the EU Shapes the Scope of Regulatory Reforms in Transition Countries.” European Union Politics 5 (3):307-330. doi: 10.1177/1465116504045155.

Mejdini, Fatjona. 2016, 03 May. “Chinese Investments Raise Eyebrows in Albania.” BalkanInsight. www.balkaninsight.com/en/article/chinese-investments-raise-eyebrows-in-albania-05-02-2016.

Mogherini, Federica. 6 March 2017. Remarks by the High Representative/Vice-President Federica Mogherini following the Foreign Affairs Council Brussels.

Osnos, Evan. 2018. “Making China Great Again. As Donald Trump surrenders America’s global commitments, Xi Jinping is learning to pick up the pieces.” The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/01/08/making-china-great-again.

Poggetti, Lucrezia. 2017, 24 April. “China’s Charm Offensive in Eastern Europe Challenges EU Cohesion.” The Diplomat https://thediplomat.com/2017/11/chinas-charm-offensive-in-eastern-europe-challenges-eu-cohesion/.

Rama, Edi. 5 December 2017. EU must marry Western Balkans quickly to avoid new risks. Brussels: Friends of Europe, https://www.euractiv.com/section/enlargement/news/eu-must-marry-western-balkans-quickly-to-avoid-new-risks-albania-pm/.

Rapoza, Kenneth. 2017, 10 March. “China Courts Albania Investment While U.S. Pushes Politics.” Forbes.

Rapoza, Kenneth 2016. “Albania Becomes Latest China Magnet.” Forbes, (https://www.forbes.com/sites/kenrapoza/2016/06/13/albania-becomes-latest-china-magnet/#81f12ac24901).

Reuters. 2020, 3 Avril. “Russia sends medical aid to Serbia to fight coronavirus.” https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-russia-serbia/russia-sends-medical-aid-to-serbia-to-fight-coronavirus-idUSKBN21L17H.

SGTN. 2020, 17 March. Serbia’s state of emergency: ‘China is the only country that can help’. https://youtu.be/P42OrsA045M?t=17.

The Economist. 2017, 15 May. “What is China’s belt and road initiative? The many motivations behind Xi Jinping’s key foreign policy.”

Todorova, Maria. 1997. Imagining the Balkans. 2nd ed. New York: Oxford University Press. Reprint, 2009.

Trade. 2017. “European Union, Trade in goods with Albania: http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2006/september/tradoc_113342.pdf.”

Trading Economics. 2018. “Albania Foreign Direct Investment 2004-2018.” https://tradingeconomics.com/albania/foreign-direct-investment.

Wood, Vincent. 2017, 18 April. “EU NIGHTMARE: Albania threatens Brussels ‘give us membership or prepare for CHAOS’.” Express. https://www.express.co.uk/news/world/793091/EU-Albania-membership-war-European-Union-Balkans-free-movement-Edi-Rama.

World Bank. 2013. Overview of the Research and Innovation Sector in the Western Balkans. In Western Balkans Regional R&D Strategy for Innovation Washington, DC: World Bank.

Xinhua. 2020, March 17. China sends first batch of medical aid to Serbia to help fight COVID-19. edited by http://en.people.cn/n3/2020/0317/c90000-9668981.html.

Yoruk, Murat-Ahmet. 2008, 16 April. “Perspektiva te reja ekonomike midis turqise dhe Shqiperise.” Gazeta Shqiptare, www.balkanweb.com/site/perspektiva-te-reja-ekonomike-midis-turqise-dhe-shqiperise/.

Zakaria,

Fareed. 2008, 12 March. “The rise of the rest.” Newsweek

https://fareedzakaria.com/columns/2008/05/12/the-rise-of-the-rest.

[1] The decision was backed up by a package of aid for all the countries of the Wester Balkans Six, after criticism for lack of solidarity. Brussels announced 40-million-euro aid to help WB6, 15 to Serbia, four million to Albania and North Macedonia, five million to Kosovo, seven million to Bosnia-Herzegovina and three million to Montenegro. 374 million will be allocated to help cushion the economic impact of the epidemic. WB countries will also be allowed to take part in an EU joint procurement program to buy protective medical equipment (EURACTIV 2020, 30 March).

[2] Lasheras de Borja et al. Return to instability: How migration and great power politics threaten the Western Balkans. (London, European Council on Foreign Relations, 2016)

[3] European Commission. “A credible enlargement perspective for and enhanced EU engagement with the Western Balkans.” (2018) https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/communication-credible-enlargement-perspective-western-balkans_en.pdf.

[4] Federica Mogherini. Remarks by the High Representative/Vice-President Federica Mogherini following the Foreign Affairs Council Brussels. (2017)

[5] Amaël Cattaruzza. L’affirmation de l’Union européenne dans les Balkans. Vers une politique d’intégration régionale… mais de quelle région? Strates: Matériaux pour la Recherche en Sciences Sociales 15 (http://journals.openedition.org/strates/6688) 2008.

[6] Maria Todorova. Imagining the Balkans. 2nd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press. Reprint, 2009.)

[7] Enika Abazi and Albert Doja. The past in the present: time and narrative of Balkan wars in media industry and international politics. Third World Quarterly 38 (4):1012-1042. doi: 10.1080/01436597.2016.1191345. 2017.

[8] They include Germany’s premature recognition of Slovenian and Croatian secession from Yugoslavia (1991). The resentment of the increasing US influence after Dayton Agreement (1995), South Balkan Development Initiative (1995) and Southeast European Cooperative Initiative (1996), that provoked the French initiated Royaumont Process (1995) that was launched one day before the Dayton Agreement leaded by the Americans (Ehrhart 1999, 331), complemented by German presidency initiative on the Southeast European Stability Pact initiative (1999) that was lunched to confirm the EU “irretrievably committed to becoming a Balkan power with specific responsibilities and interests” (European Parliament 30 April 1998).

[9] Xinhua. China sends first batch of medical aid to Serbia to help fight COVID-19. http://en.people.cn/n3/2020/0317/c90000-9668981.html. (2020, March 17.)

[10] Gazeta Dita. Plani C dhe Plani D. http://www.gazetadita.al/vetem-rama-nderron-qendrim-nese-bota-permbyset-kemi-turqine/. 2020, 22 March.

[11] Milo Đukanović. Twitter: https://twitter.com/i/status/1247854322358128640 (2020, 8 April.)

[12] Reuters. Russia sends medical aid to Serbia to fight coronavirus. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-russia-serbia/russia-sends-medical-aid-to-serbia-to-fight-coronavirus-idUSKBN21L17H. (2020, 3 April.)

[13] Inspired by Fareed Zakaria (2008, 12 March)

[14] Evan Osnos. Making China Great Again. As Donald Trump surrenders America’s global commitments, Xi Jinping is learning to pick up the pieces. (The New Yorker, 2018.) https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/01/08/making-china-great-again

[15] Edi Rama. EU must marry Western Balkans quickly to avoid new risks. https://www.euractiv.com/section/enlargement/news/eu-must-marry-western-balkans-quickly-to-avoid-new-risks-albania-pm/. (Brussels: Friends of Europe, 5 December 2017.)

[16] Vincent Wood. EU NIGHTMARE: Albania threatens Brussels ‘give us membership or prepare for CHAOS. (Express. 2017, 18 April.) https://www.express.co.uk/news/world/793091/EU-Albania-membership-war-European-Union-Balkans-free-movement-Edi-Rama.

[17] European Commission. A credible enlargement perspective for and enhanced EU engagement with the Western Balkans. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/sites/beta-political/files/communication-credible-enlargement-perspective-western-balkans_en.pdf. (2018)

[18] Ibid. European Commission. 2018

[19] Enika Abazi et al. 2008. Albania and European Union: Rethinking EU Integration, http://www.houseofeurope.org/pdf/Perceptions_2008.pdf. (Tirana: AIIS. 2008.)

[20] AIIS. The European Perspective of Albania: Perceptions and Realities. (Tirana: AIIS press. 2014)

[21] INSTAT. Foreign Enterprises in Albania 2014-2016 http://www.instat.gov.al/media/3663/foreign-enterprises-in-albania.pdf (Tirana, 2017)

[22] Walter Mattli and Thomas Plümper. The Internal Value of External Options: How the EU Shapes the Scope of Regulatory Reforms in Transition Countries. (European Union Politics 5 (3):307-330. doi: 10.1177/1465116504045155. 2014.)

[23] Lucrezia Poggetti. China’s Charm Offensive in Eastern Europe Challenges EU Cohesion. (The Diplomat https://thediplomat.com/2017/11/chinas-charm-offensive-in-eastern-europe-challenges-eu-cohesion/. 2017, 24 April.)

[24] European Union. European Union, Trade in goods with Albania: http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2006/september/tradoc_113342.pdf.

[25] Kenneth Rapoza. China Courts Albania Investment While U.S. Pushes Politics. (Forbes. 2017, 10 March.)

[26] Kenneth Rapoza, Albania Becomes Latest China Magnet. Forbes, 2016. (https://www.forbes.com/sites/kenrapoza/2016/06/13/albania-becomes-latest-china-magnet/#81f12ac24901).

[27] Ibid.

[28] Fatjona Mejdini. Chinese Investments Raise Eyebrows in Albania. (Balkan Insight. www.balkaninsight.com/en/article/chinese-investments-raise-eyebrows-in-albania-05-02-2016. 2016, 03 May.)

[29] Xi Jinping. Report at 19th CPC National Congress. (Beijing: Xinhua: www.xinhuanet.com/english/download/Xi_Jinping’s_report_at_19th_CPC_National_Congress.pdf. 2017.)

[30] Saul Estrin and Milica Uvalic. Foreign Direct Investment in the Western Balkans: What Role Has it Played During Transition? (2016. Comparative Economic Studies 58 (3):455–483.)

[31] Will Bartlett and Ivana Prica. The Variable Impact of the Global Economic Crisis in South East Europe, LSEE Papers. (London: LSE European Institute. 2012.)

[32] Jens Bastian. The potential for growth through Chinese infrastructure investments in Central and South-Eastern Europe along the “Balkan Silk Road”, www.ebrd.com/documents/policy/the-balkan-silk-road.pdf (European Bank for Construction and Development. London. 2017.)

[33] Vladislav Kurbatskiy. Albania and Russia Rapprochement. Moscow: http://russiancouncil.ru/en/analytics-and-comments/analytics/albania-and-russia-rapprochement/: (RIAC. 2012.)

[34] European Union. Trade in goods with Albania: http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2006/september/tradoc_113342.pdf (2012.)

[35] John Cappello. Russia Escalates Disinformation Campaign in Western Balkans. www.defenddemocracy.org/media-hit/john-cappello-russia-escalates-disinformation-campaign-in-western-balkans/. (2017, 05 April.)

[36] John Cappello. Russia Ramps Up Media and Military Influence in Balkans. (Washington: Foundation for Defense of Democracies (FDD): http://www.defenddemocracy.org/media-hit/john-cappello-russia-ramps-up-media-and-military-influence-in-balkans/. 2017, 13 October.)

[37] David Corn et al. How a Russian-Linked Shell Company Hired An Ex-Trump Aide to Boost Albania’s Right-Wing Party in DC. (. 6 March 2018. Mother Jones. https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2018/03/how-a-russian-linked-shell-company-hired-an-ex-trump-aide-to-boost-albanias-right-wing-party-in-dc/.)

[38] Enika Abazi. A New Power Play in the Balkans: Kosovo’s Independence. (Insight Turkey 10 (2):67-80.)

[39]European Union. European Union, Trade in goods with Albania: http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2006/september/tradoc_113342.pdf.

[40] Murat-Ahmet Yoruk. Perspektiva te reja ekonomike midis turqise dhe Shqiperise. (Gazeta Shqiptare, 2008, 16 April) www.balkanweb.com/site/perspektiva-te-reja-ekonomike-midis-turqise-dhe-shqiperise/.

[41] Trading Economics. Albania Foreign Direct Investment 2004-2018. (2018.) https://tradingeconomics.com/albania/foreign-direct-investment.

[42] INSTAT. Foreign Enterprises in Albania 2014-2016 Tirana: http://www.instat.gov.al/media/3663/foreign-enterprises-in-albania.pdf. 2017.

[43] European Union. “European Union, Trade in goods with Albania: http://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2006/september/tradoc_113342.pdf.”

[44] Ahmet Davutoglu. Turkey’s Foreign Policy Vision: An Assessment of 2008. (Insight Turkey 10 (1):77-96. 2008.)

[45] Such as South East European Cooperation Process, the Regional Cooperation Council, Southeast European Cooperative Initiative, Peace Implementation Council, and South-Eastern Europe Brigade and recently supporting the Western Balkans Fund Secretariat in Tirana.

[46] Ahmet Davutoglu. Turkey’s Foreign Policy Vision: An Assessment of 2008. (Insight Turkey 10 (1):77-96.)

[47] Turkish Cooperation and Coordination Agency

[48] Turkish Directorate of Religious Affairs.

[49] Fareed Zakaria. The rise of the rest. (Newsweek 2008, 12 March.) https://fareedzakaria.com/columns/2008/05/12/the-rise-of-the-rest

[50] IMF. Country Report Albania: Selected Issues. 2017 17/374

[51] INSTAT. Foreign Enterprises in Albania 2014-2016 (Tirana, 2017) http://www.instat.gov.al/media/3663/foreign-enterprises-in-albania.pdf.

[52] EU Data. Albania On Its European Path. (Brussels, 2018)

[53] European Commission, IPA II. Revised Indicative Strategy Paper For Albania (2014-2020). (Brussels. 2018)

[54]EU Data. Albania On Its European Path. (Brussels, 2018)

[55] World Bank. Overview of the Research and Innovation Sector in the Western Balkans. (Western Balkans Regional R&D Strategy for Innovation. Washington, DC: World Bank. 2013.)

[56] Ibid.

[57] Enika Abazi. Albania in Europe: Perspectives and Challenges. (Eurasian Files (Avrasya Dosyasi): International Relations and Strategic Studies 14 (1):229-252, 2013 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01142295.)

[58] Ismail Kadare. Identiteti Europian i Shqiptarëve: sprovë [Albanian European Identity]. (Tirana: Onufri. 2006.)

[59] Jens Bastian. The potential for growth through Chinese infrastructure investments in Central and South-Eastern Europe along the “Balkan Silk Road”, www.ebrd.com/documents/policy/the-balkan-silk-road.pdf, (European Bank for Construction and Development. London. 2017.)

[60] The Economist. What is China’s belt and road initiative? The many motivations behind Xi Jinping’s key foreign policy. (2017, 15 May.)

[61] John Cappello. Russia Escalates Disinformation Campaign in Western Balkans. www.defenddemocracy.org/media-hit/john-cappello-russia-escalates-disinformation-campaign-in-western-balkans/. (2017, 05 April.)

[62] Darko Janjevic. Erdogan wants Balkans as ‘leverage’ on Europe. (Deutsche Welle, 2017. (www.dw.com/en/erdogan-wants-balkans-as-leverage-on-europe-expert/a-38009794).